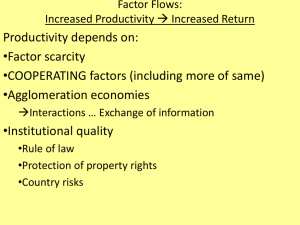

European Integration: A Review of the Literature and Lessons for NAFTA

advertisement