market intelligence WHICH WAY NEXT FOR HEDGE FUNDS? INVESTORS

advertisement

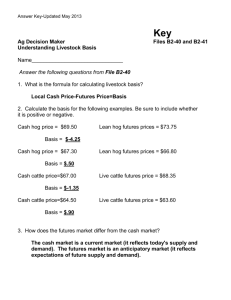

market intelligence This article is an extract from the 225-page report: WHICH WAY NEXT FOR HEDGE FUNDS? A GUIDE FOR MANAGERS, BANKS AND INVESTORS EDITED BY DAVID WALKER www.ifrmarketintelligence.com SECTION QUANT SYSTEMS – THE FUTURE FOR SYSTEMATIC APPROACHES 07 31 CHAPTER By Georgia Nakou, Altis Partners (Jersey) Limited Summer 2007 stands alongside 1998 as a black period in the annals of the hedge fund industry. A number of high-profile hedge fund implosions, coming at a time when ordinary consumers were beginning to suffer the effects of a faltering housing market, made headline news in the popular media and the industry press alike. The most traumatic and public losses were experienced by systematic managers trading long/short equity portfolios, particularly statistical arbitrage funds. Bad press for quantitative strategies In the wake of headlines along the lines of ‘Attack of the killer quants’ and ‘The end for quant systems’, implying that fault lay with the practice of systematic trading, many investors began to question the validity of quantitative strategies across the board. This was a good story, which cast quant managers in the role of Frankenstein, defeated by their own technology gone wrong. However, there are reasons for believing that the truth is both more simple and more complicated. The implications are far-reaching, for quants of all stripes as well as for other market participants. At Altis, we experienced these events from the standpoint of a managed futures adviser. In our business, we employ a proprietary systematic programme to trade futures markets across all sectors. This corner of the hedge fund industry suffered its own less spectacular casualties in the summer of 2007, in ways that cannot be related directly to the woes of the long/short equity quants. However, the lessons learned may turn out to be quite similar. In one of the more widely disseminated post-mortems on summer 2007, two MIT academics, Andrew Lo and Amir Khandani, produced a study attempting to explain the spate of collapses in the systematic long/short equity sector1. Their hypothesis was that the closely timed implosions across the sector could have been set off by the liquidation of just one equity fund portfolio or proprietary trading desk. The authors acknowledged that their hypothesis could not be conclusively verified; until someone owns up to being the hedge fund or prop desk in question, the ‘unwinding’ theory remains merely a plausible story. More interesting is the incidental evidence put forward in Lo and Khandani’s paper. Their analysis concluded that the systematic nature of the funds involved had no direct bearing on the events of August 2007. More worrying, the authors argue that the greater interconnectedness of the financial universe has resulted in increased systemic risk, meaning that events in one part of the financial system can more easily infect other parts that have conventionally been regarded as remote and unrelated. Thus, the failure of the sub-prime mortgage lending and structured debt business model was able to propagate to a distant niche of the financial system with catastrophic consequences. Within this increasingly interrelated universe, the hedge fund world itself is becoming more closely connected, showing increasing long-term correlations between strategies. Several reviewers have focused on the evidence of convergence and cross-pollination between equity quant strategies and the significant overlaps resulting in their portfolios, making them more vulnerable to the same market shocks. Others have long argued that overcrowding in the hedge fund space has led to a deterioration of returns and an increase of systemic risk. It could, in fact, be argued that hedge funds are themselves acting as a conduit for risk between different parts of the financial system, through the use of derivatives and the cross-trading of different market sectors and asset classes. CTAs: The ‘other’ quants Regardless of the subtleties of some of these interpretations, the idea that quant systems as a category were irredeemably damaged during this episode has entered the industry’s folklore. However, the reality is more complex. While it is true that long/short equity systems did suffer for 1 Amir E. Khandani and Andrew W. Lo (2007) What Happened to the Quants in August 2007? (unpublished paper). 171 www.ifrmarketintelligence.com © Thomson Reuters 2008 SECTION07 CHAPTER31 ifrintelligence reports/Which way next for hedge funds? A guide for managers, banks and investors some of the reasons mentioned above, they are not the only quantitative systems and their experience is by no means definitive. Below we review the events from the standpoint of a systematic managed futures adviser and conclude with some of the lessons learned in this sector. Managed futures advisers, or CTAs (commodity trading advisers, to give them their regulatory moniker), have a long tradition of systematic trading with roots in the 1970s. CTAs take advantage of the diversification, leverage and liquidity offered by the futures markets to generate returns that are uncorrelated to traditional asset classes and to most other hedge fund strategies. Most CTAs tend to gravitate towards quantitative approaches purely because they allow them to trade the variety of instruments to which the futures markets give access. Historically, the most popular strategy among systematic CTAs has been trend-following. This involves applying a simple indicator of persistence of market movement, for example a pair of moving averages, to a number of markets and betting on the continuation of a trend. It is possible to construct a diversified portfolio by simply adding different markets and moving average timeframes. Such a portfolio can provide exposure to a huge variety of market sectors, including commodities, interest rates and currencies, as well as equity markets. Since the 1980s, simple systems of this type have demonstrated their ability to generate outstanding returns. The CTA sector has evolved over the years, but while some managers have graduated to more complex and sophisticated systems, simple trend following has remained popular. Being potentially a more diversified strategy in terms of exposure to different market sectors, CTAs experienced the events of July/August 2007 very differently from equity quants. The effect was a ‘slow motion crash’ starting in the final week of July and continuing into early August. A series of synchronised directional changes started in equities and bonds, spread to currencies and eventually affected the commodities, and especially metals, in a kind of domino effect. This constellation of events resulted in two losing months across almost the entire managed futures sector. Some of the oldest and biggest names in the industry were brought to their knees by double-digit monthly losses. Others suffered more moderate losses of a few percentage points, truly unexceptional for what can be a highly volatile strategy. Altis fell into the latter group. Several industry experts recognised in these results a symptom of changes in the markets and the managed futures industry that have been a topic of research and discussion in recent years, namely the influence of crowding and institutionalisation. These developments in the industry have prompted several commentators to warn in recent years that simple trend-following was becoming increasingly ill-equipped for the changing conditions, and that managers need to adapt if they are to survive and produce high returns in the long term. On the one hand, there has been a rapid growth in assets managed in the sector, and an increasing number of mega-managers. Assets in managed futures have gone from US$1.5bn in the 2 mid-1980s to over US$200bn today and have increased fivefold over the last decade alone ; there are now a number of multi-billion dollar CTAs throwing their weight around in the markets. By trading increasing amounts of client money on the markets, such funds run the risk of moving the markets. For strategies that harvest their returns from the exploitation of small inefficiencies in market behaviour, ‘becoming the market’ in this way is at best harmful to profitability, and at worst dangerous for themselves and other market participants. Second, there is increased institutionalisation. This manifests itself in two ways. On the one hand, there is the old issue of cross-fertilisation: people inducted into the world of managed futures through a few pioneering firms have gone on to head research departments or start their own funds equipped with the same fundamental trading techniques. Managers are also ‘institutionalised’ through responding to the demands of a similar set of clients for certain types of exposure, certain risk profiles and so on. The benchmarks were generally set by the first generation of successful CTAs, and discouraged deviation from the ‘tried and tested’ trend-following models. An inevitable outcome of these twin trends has been more and larger managers trading similarly behaving systems in increasingly crowded markets. So the behaviour of systematic funds is itself creating hazardous conditions. In these conditions, it is less profitable, as well as potentially dangerous, to be one of the stampeding herd. It pays to be different, and in order to do so one needs to understand the issues at hand and put oneself in a position to use them to advantage. 2 According to Barclay Hedge. 172 SECTION07 CHAPTER31 ifrintelligence reports/Which way next for hedge funds? A guide for managers, banks and investors Technology is (only part of) the answer When faced with the failure (or potential failure) of a technical system, the first reaction is to look for a technical ‘fix’. In interviews following summer 2007, some of the more damaged quant managers spoke of going back to the drawing board and fundamentally reconceptualising their systems using new techniques such as artificial intelligence, agent-based modelling and machine learning. While there might be ‘geek value’ in this approach, it is not a viable business solution for most managers, nor does it show a willingness really to understand and learn from events. There are, of course, technical responses to the issues posed by last summer, one of which we outline below, but there are also valuable lessons for quant managers as businesses, which the managed futures industry seems to be coming around to. There are also lessons for investors in seeking to identify managers who are well equipped to deal with a changing world. At a technical level, the issue is about how systematic funds deal with extreme events and changing market conditions. This presupposes a recognition that relationships across markets are not stationary; they can reverse rapidly, particularly during times of stress. Altis has been developing the concept of ‘market coherence’ as a way of approaching the potential effects of market interconnectedness. Coherence describes conditions where seemingly unrelated markets may be responding to common drivers of returns and behaving in a coordinated manner. ‘Coherent’ periods are the most profitable for trend-following strategies, but there is a sting in the tail. Coherence is a long-term phenomenon, allowing trend-following systems to build up strong positions; but while coherent periods last for months, reversals only take days. Building up trendfollowing positions in these conditions while relying on historical correlations can add up to one big risky bet, even in a seemingly well-diversified portfolio. Backward-looking correlation models, including the traditional mean-variance approach to portfolio construction, are incredibly vulnerable to changing correlations. The characteristic of big, systemic moves such as those experienced over the summer of 2007 is that they cut across sectors in seemingly unpredictable ways. An alternative approach would allow a system to take advantage of market coherence, while reducing the risk of getting trapped in adverse positions during the inevitable reversals. The ‘heat maps’ in Figures 31.1 and 31.2 demonstrate in a schematic way how such a solution can be approached. The images show the difference between historical correlations (left) and forward correlations (right) in a sample portfolio of 26 markets3. 3 This analysis uses the results of simulations and is used for illustrative purposes only. Care should be taken when interpreting simulations, as they may not represent conditions found in actual trading. 173 SECTION07 CHAPTER31 ifrintelligence reports/Which way next for hedge funds? A guide for managers, banks and investors Figure 31.1: Historic versus forecast correlations showing build-up of market coherence EC ADCDED B L TY BF G SPDF Q GC SI HG CLHU NG C S W CTKCCC LC LH EC EC EC AD AD AD CD CD CD ED ED ED B B B L L L TY TY TY BF BF BF G G G SP SP SP DF DF DF Q Q Q GC GC GC SI SI SI HG HG HG CL CL CL HU HU HU NG NG NG C C C S S S W W W CT CT CT KC KC KC CC CC CC LC LC LC LH LH LH EC ADCDED B L TY BF G SPDF Q GC SI HG CLHU NG C S W CTKCCC LC LH 100 90 80 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 EC ADCDED B L TY BF G SPDF Q GC SI HG CLHU NG C S W CTKCCC LC LH EC EC AD AD CD CD ED ED B B L L TY TY BF BF G G SP SP DF DF Q Q GC GC SI SI HG HG CL CL HU HU NG NG C C S S W W CT CT KC KC CC CC LC LC LH LH EC ADCDED B L TY BF G SPDF Q GC SI HG CLHU NG C S W CTKCCC LC LH EC AD CD ED B L TY BF G SP DF Q GC SI HG CL HU NG C S W CT KC CC LC LH February 2003: Historic (left) and forecast (right) correlations Source: Altis Partners Figure 31.2: Historic versus forecast correlations showing dissipation of market coherence EC ADCDED B L TY BF G SPDF Q GC SI HG CLHU NG C S W CTKCCC LC LH EC EC EC AD AD AD CD CD CD ED ED ED B B B L L L TY TY TY BF BF BF G G G SP SP SP DF DF DF Q Q Q GC GC GC SI SI SI HG HG HG CL CL CL HU HU HU NG NG NG C C C S S S W W W CT CT CT KC KC KC CC CC CC LC LC LC LH LH LH EC ADCDED B L TY BF G SPDF Q GC SI HG CLHU NG C S W CTKCCC LC LH 100 90 80 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 EC ADCDED B L TY BF G SPDF Q GC SI HG CLHU NG C S W CTKCCC LC LH EC EC EC AD AD AD CD CD CD ED ED ED B B B L L L TY TY TY BF BF BF G G G SP SP SP DF DF DF Q Q Q GC GC GC SI SI SI HG HG HG CL CL CL HU HU HU NG NG NG C C C S S S W W W CT CT CT KC KC KC CC CC CC LC LC LC LH LH LH EC ADCDED B L TY BF G SPDF Q GC SI HG CLHU NG C S W CTKCCC LC LH December 2002: Historic (left) and forecast (right) correlations Source: Altis Partners The map of historical correlations uses standard day-to-day market correlation. The forward correlations in this case have been constructed using expected returns from a simple trend-following model. Reading lighter areas as high correlations, we can see that a marked difference between historic and forecast relationships (an increase or decrease in ‘market heat’) can effectively signal a build-up of market coherence, or a dissipation as markets correct. This provides a strong tool for controlling exposure to correlated risks. The Altis system already uses such measures successfully. This was recently demonstrated in the period of February/March 2008. Here, strong trends across the markets gave the system a record monthly return in February (+22%). Towards the end of the month, however, the system detected strong correlations across its positions and reacted not by increasing the size of its bets but by scaling back its overall exposure. The result was a protected position that dampened potential losses from the subsequent reversal. 174 SECTION07 CHAPTER31 ifrintelligence reports/Which way next for hedge funds? A guide for managers, banks and investors Our approach to the general problem of dealing with changing market conditions has been to build a system that is flexible and sensitive to changing market relationships. Our philosophy, which has been vindicated both by summer 2007 and any number of market reversals before and after, is that a trading system needs to be robust at its core, but open to incremental improvement. In other words, we believe that research pays as long as the fundamentals are strong. Managers who have been wedded to ‘unreconstructed’ trend-following systems have suffered, but those who recognise that markets change have been better equipped to weather the storm and distinguish themselves in difficult trading conditions. The implication for managers as businesses is that there always needs to be a strategic balance between priorities and an interplay between research and development and asset growth as a business develops. Neglect of the core product is now more likely than ever to lead to unpleasant surprises for managers and their investors. Georgia Nakou is senior investment systems adviser for Altis Partners (Jersey) Limited. She is an experienced researcher in a number of fields including hedge funds and managed futures, energy and environmental policy, and was awarded a DPhil from Oxford University in 2001. Altis is a systematic managed futures manager which uses a quantitative system to trade a diversified futures portfolio.. The firm has been trading continuously since 2001 with annualised returns of over 20% and now manages over US$ 1 billion of client funds in its two products. 175