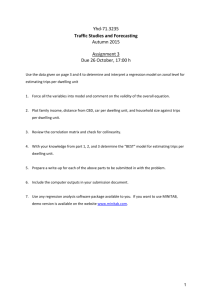

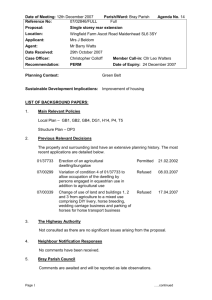

/ Enabling Housing

advertisement