RNM/OECS COUNTRY STUDIES TO INFORM TRADE NEGOTIATIONS: DOMINICA

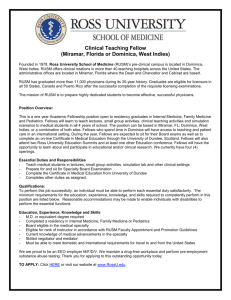

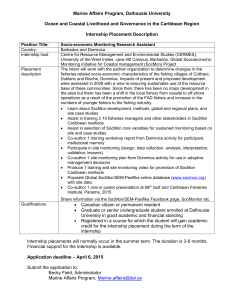

advertisement