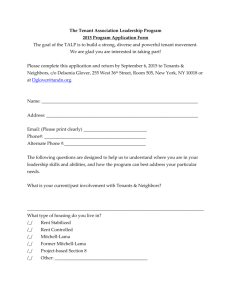

1 TENANT HOUSING DEVELOPMENT PROCESS by

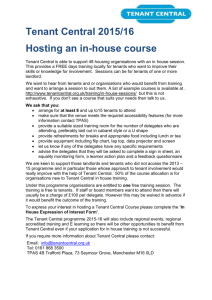

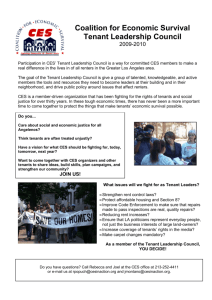

advertisement