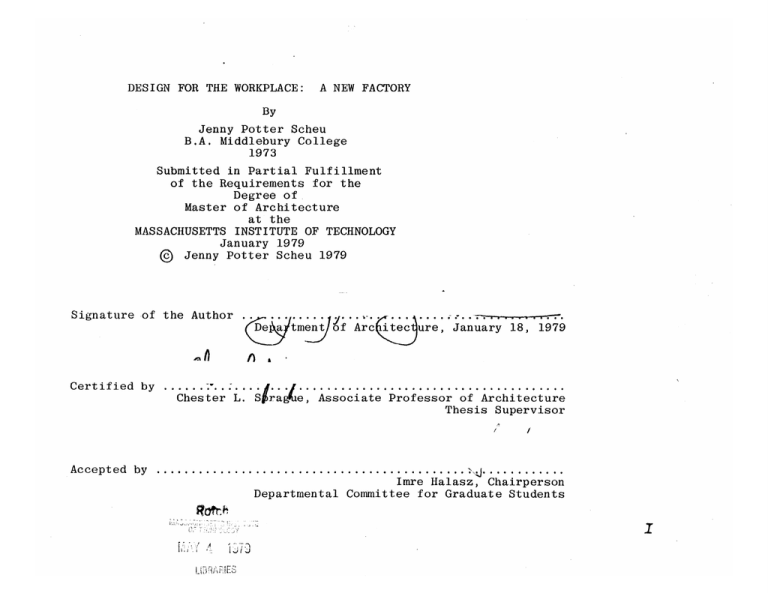

1979

advertisement