EXPANDING IN SUBSIDIZED by M. Phillips Loftin

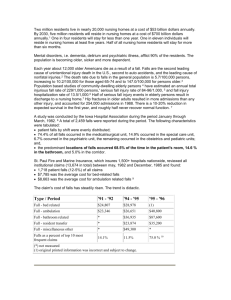

advertisement