National Register of Historic Places u

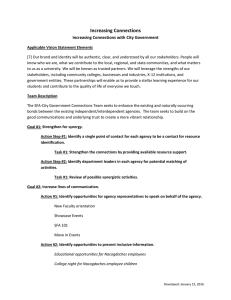

advertisement