MAMMALS OF MISSISSIPPI 7:1-6 Muskra RYAN T. LANGLEY

advertisement

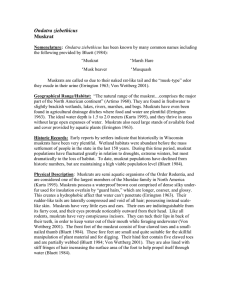

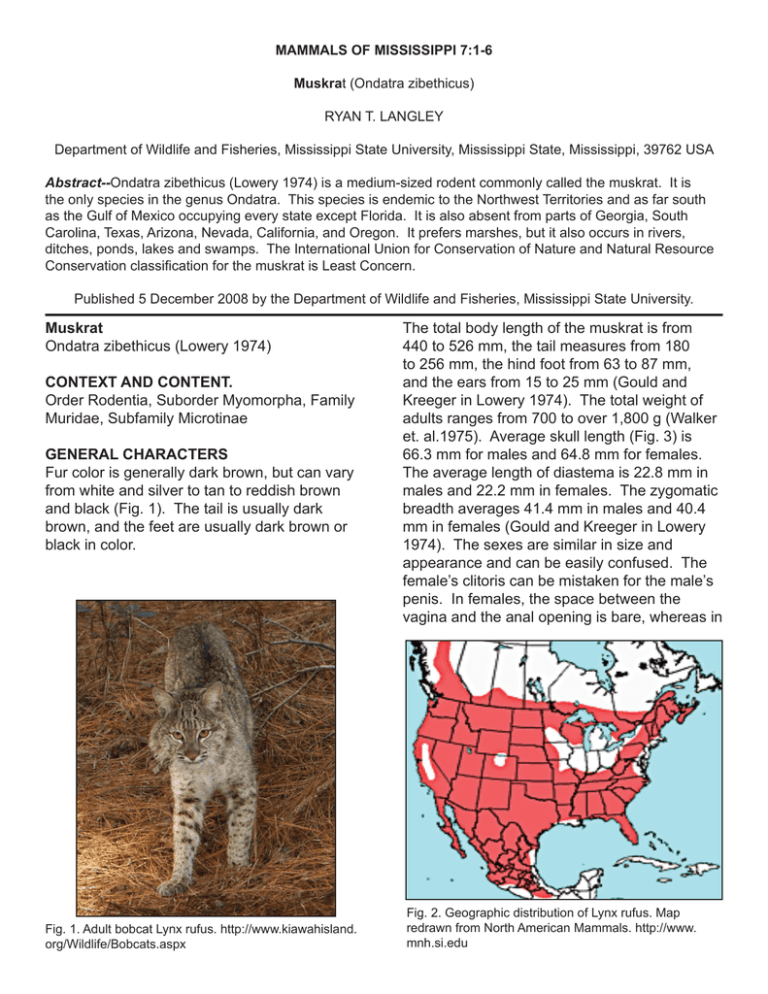

MAMMALS OF MISSISSIPPI 7:1-6 Muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) RYAN T. LANGLEY Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Mississippi State University, Mississippi State, Mississippi, 39762 USA Abstract--Ondatra zibethicus (Lowery 1974) is a medium-sized rodent commonly called the muskrat. It is the only species in the genus Ondatra. This species is endemic to the Northwest Territories and as far south as the Gulf of Mexico occupying every state except Florida. It is also absent from parts of Georgia, South Carolina, Texas, Arizona, Nevada, California, and Oregon. It prefers marshes, but it also occurs in rivers, ditches, ponds, lakes and swamps. The International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resource Conservation classification for the muskrat is Least Concern. Published 5 December 2008 by the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, Mississippi State University. Muskrat Ondatra zibethicus (Lowery 1974) CONTEXT AND CONTENT. Order Rodentia, Suborder Myomorpha, Family Muridae, Subfamily Microtinae GENERAL CHARACTERS Fur color is generally dark brown, but can vary from white and silver to tan to reddish brown and black (Fig. 1). The tail is usually dark brown, and the feet are usually dark brown or black in color. Fig. 1. Adult bobcat Lynx rufus. http://www.kiawahisland. org/Wildlife/Bobcats.aspx The total body length of the muskrat is from 440 to 526 mm, the tail measures from 180 to 256 mm, the hind foot from 63 to 87 mm, and the ears from 15 to 25 mm (Gould and Kreeger in Lowery 1974). The total weight of adults ranges from 700 to over 1,800 g (Walker et. al.1975). Average skull length (Fig. 3) is 66.3 mm for males and 64.8 mm for females. The average length of diastema is 22.8 mm in males and 22.2 mm in females. The zygomatic breadth averages 41.4 mm in males and 40.4 mm in females (Gould and Kreeger in Lowery 1974). The sexes are similar in size and appearance and can be easily confused. The female’s clitoris can be mistaken for the male’s penis. In females, the space between the vagina and the anal opening is bare, whereas in Fig. 2. Geographic distribution of Lynx rufus. Map redrawn from North American Mammals. http://www. mnh.si.edu 1958). They are weaned about 4 weeks after birth (Lowery 1974). During the second month after birth, the tail becomes laterally flattened (Errington 1963). Muskrats usually become sexually mature the spring following their birth (Errington 1963). Fig. 3.––Distribution of Mustela frenata in North America. males the area between the penis and the anal opening is well furred (Gould and Kreeger in Lowery 1974). DISTRIBUTION Muskrats range from northern Alaska and Canada to the southern United States (Fig. 2). Muskrats occur throughout the state of Mississippi and Louisiana. They are absent from Florida, and parts of Georgia, South Carolina, Texas, Arizona, Nevada, California, and Oregon (Lowery 1974). FORM AND FUNCTION Most females have two pairs of mammae between the front and hind legs, one pectoral pair and two pairs in the groin. Some have been known to have up to 4 or 5 pairs if mammae (Godin 1977). The dental formula is i 1/1, c 0/0, p 0/0, m 3/3 (Hall and Kelson 1959). The muskrat has large incisors well suited for gnawing and transporting objects through the water. The lips can close behind the incisors to keep water out of the mouth when gnawing under water (Godin 1977). ONTOGENY AND REPRODUCTION Muskrat neonates are blind with little hair and a pink to grey color with a rounded tail (Errington 1963). Incisors begin to erupt between 6 and 7 days, and the eyes open between 14 and 16 days post-parturition. Young muskrats are covered with a soft fur and are able to swim within 14 days of birth (Erikson 1963; Sather Muskrats in Mississippi breed throughout the year, with reproductive activity peaking during winter (O’Neil 1949). Estrous cycles last between 3 to 6 days (McLeod and Bondar 1952). Average litter size varies from 4 to 8 young, with muskrats living in poor habitat having fewer young per litter and fewer litters per year (Neal 1968). Spermatogenesis occurs from spring, through late fall (Errington 1963; Forbes 1942). ECOLOGY The major cause of muskrat mortality is trapping for fur (Errington 1963). The typical lifespan of a muskrat is 3 to 4 years (Godin 1977). Muskrats dig burrows into banks and also create conical houses with underwater tunnels to the entrances (MacArther and Aleksiuk 1979). Muskrat burrows can damage river and pond banks, and can also affect agricultural land. The two types of houses constructed by muskrats are main dwellings and feeding houses (Dozier 1948a). Feeding houses are usually smaller than the main dwellings and are usually largest in the winter, with thicker walls and floors (MacArther and Aleksiuk 1979). The average size of a muskrat house ranges from 1 to 2 m in diameter at the base and from 600 to 1200 mm in height. Muskrat houses provide a dry nest area, and protection from predators and weather (Lowery 1974). House construction begins during ice-free periods usually peaking between May and early June, and again in October (Danell 1978). Temperatures inside muskrat houses are higher than ambient temperature (Earhart 1969). Diet consists of aquatic vegetation, and occasionally some animal matter. Muskrats living in marshes typically feed on cattails (Typha), alligator grass (Alternanthera philoxeroides), Roseau cane (Phragmites communis) shoots, delta duck potato (Sagittaria platyphylla), and dog-tooth grass (Panicum repens). In the brackish Subdelta, their diet consists of wire grass (Spartina patens), hogcane (Spartina cynosuroides), Roseau cane (Phragmites communis) shoots, giant bulrush (Scirpus californicus), coco grass (Scirpus robustus), oystergrass (Spartina alternatiflora), spike rush tubers (Eleocharis sp.), delta duck potato, pickerelweed (Pontederia cordata), and black rush (Juncus roemerianus). In fresh Subdelta marshes, plants eaten are paille fine (Panicum hemitomon), cattails, wapato (Sagitarria latifolia), Roseau cane shoots, giant bulrush, and softstem bulrush (Scirpus validus). In prairie marshes, muskrats eat coco grass, wiregrass, hogcane, cattails, bulrush, lakegrass, salt grass (Distichlis spicata), dwarf spike rush (Eleocharis parvula), black rush, pickerelweed, Roseau cane shoots, oystergrass, and alligator weed (Lowery 1974). Some diseases associated with the muskrat include: adiasspiromyosis (Otcenasek et al. 1974), epizootic chlamydiosis (Spalatin et al. 1971), hemorrhagic disease (Errington 1963), leptospirosis (Al Saadi and Post 1976), pseudotuberculosis (Langford 1972), ringworm disease (Errington 1963), salmonellosis (Armstrong 1942), tularemia (Errington 1963), Tyzzer’s disease (Chalmers and MacNeill 1977), and yellow fat disease (Debbie 1968). The mite, Tetragonyssus spiniger, and flesh-fly larvae are abundant in the fur and nests of muskrats. Other parasites of the muskrat include: nematodes, Trichuris opaca; trematodes, Echinostoma revolutum, Plagiorchis proximus, and Quinqueserialis quinqueserialis, and cestodes Hymenolepis spp., and Taenia taeniaeformis (McKenzie and Welsh 1979). Muskrats and nutria (Myocastor coypus) have similar feeding habits consuming large quantities of stems; therefore competition may occur between the two (Wilner et al. 1979). Muskrats have many predators, especially immatures. Predators include: mink, raccoons, owls, alligators, ants, hawks, snakes, bullfrogs, gar, bowfins, snapping turtles, bass, hogs, cats, and dogs (O’Neil 1949). BEHAVIOR Muskrats become aggressive before and during the breeding season. Dominance is established through fighting, and the low ranking muskrats leave the area and are more susceptible to predators and cannibalization (Steiniger 1976). Competition for breeding sites is intense, and the larger and older members of the population occupy the best burrows. Females are more aggressive than males when defending breeding territory, sometimes killing intruders (Errington 1963). Mating occurs while partially submerged in the water. Prior to mating, scent is released from anal glands to attract a mate (Svihla and Svihla 1931). Females give birth in nest chambers of houses or in the nests of some ducks. Females care for the young, and on some rare occasions if the female dies, the male will care for the young (Errington 1963). CONSERVATION Muskrats cause extensive damage to treatment wetlands by grazing the vegetation and digging burrows in levees and berms (Kadlec et. al 2007). Muskrats can be managed by lethal and non-lethal trapping. Foothold and conibear traps are examples of lethal methods. Foothold traps hold on to the foot of the muskrat and they drown after captured. Conibear traps kill instantly when they are triggered. Muskrats can also be captured alive in a family trap, relocated and released. Family traps consist of a cage that muskrats enter and cannot exit (Snead 1950). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Jerrold L. Belant for all of his time and help formatting and revising this account. LITERATURE CITED Al Saadi, M., and G. Post. 1976. Rodent leptospirosis in Colorado. J. Wildl. Dis.,12:315-317. Armstrong, W.H. 1942. Occurrence of Salmonella typhimurium infection in muskrats. Cornell Vet., 32:87-89. Chalmers, G.A., and A.C. MacNeill. 1977. Tyzzer’s disease in wild-trapped muskrats in British Columbia. J. Wildl. Dis., 13:114116. Danell, K. 1978. Ecology of the muskrat in Northern Sweden. Rep. Natl. Swedish Environ. Protection Board.157pp. Debbie, J.G. 1968. Yellow fat disease in muskrats. New York Fish Game J.,15:119-120. Dozier, H.L. 1948. Estimating muskrat population by house counts. Trans. N. Amer. Wildlife Conf., 13:372-392. Earhart, C.M. 1969. The influence of soil texture on the structure, durability, and occupancy of muskrat burrows in farm ponds. California Fish Game, 55:179-196. Erikson, H.R. 1963. Reproduction, growth, and movement of muskrats inhabiting small water areas in New York State. New York Fish Game J., 10:90-117. Errington, P.L. 1963. Muskrat populations. Iowa State Univ. Press, Ames, 665 pp. Forbes, T.R. 1942. The period of gonadal activity in the Maryland muskrat. Science, 95:382-383. Godin, A.J. 1977. Wild mammals of New England. John Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, 304 pp. Hall, E.R., and K.R. Kelson. 1959. The mammals of North America. Ronald Press, New York, 2:547-1083 + 79 pp. Kadlec, R.H., J. Pries, and H. Mustard. 2007. Muskrats (Ondatra zibethicus) in Treatment Wetlands. Ecological Engineering 29:143-153. Langford, E.V. 1972. Pasteurella pseudotuberculosis infections in western Canada. Canadian Vet. J., 13:85-87. Lowery, H.G, Jr., 1974. The Mammals of Louisiana and its Adjacent Waters. MacArthur, R.A., and M. Aleksiuk. 1979. Seasonal microenvironments of the muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus) in a northern marsh. J. Mamm., 60:146-154. McKenzie, C.E., and H.E. Welch. 1979. Parasite fauna of the muskrat, Ondatra zibethica (Linnaeus, 1766) in Manitoba, Canada. Canadian J. Zool., 57:640-646. McLeod, J.A., and G.F. Bondar. 1952. Studies on the biology of the muskrat in Manitoba. Part I. Oestrus cycle and breeding season. Canadian J. Zool., 30:243-253. Neal, T. 1968. A comparison of two muskrat populations. Iowa State J. Sci., 43:193210. O’Neil, T. 1949. The muskrat in the Louisiana coastal marshes. Louisiana Dept. Wildlife Fish, New Orleans, 152 pp. Otcenasek, M., et al. 1974. The muskrat as reservoir in natural foci of adiaspiromycosis. Folia Parasit. (Praha), 21:55-57. Snead, I.E., 1950. A Family type live trap, handling cage, and associated techniques for Muskrats. J. Wildlife Management. 14, 67-79. Sather, J.H. 1958. Biology of the Great Plains muskrat in Nebraska. Wildl. Monogr., 2:135. Spalatin, J., J.O. Iversen, and R.P.Hanson. 1971. Properties of a Chlamydia psittaci isolated from muskrats and snowshoe hares in Canada. Canadian J. Microbiol., 17:935-942. Steiniger, Von B. 1976. Factors affecting the behavior and sociology of the muskrat (Ondatra zibethicus L.). Z. Tierpsychol. 41:55-79. (in German, English summary.) Svihla, A., and R.D. Svihla. 1931. The Louisiana muskrat. J. Mamm., 12:12-28. Walker, E.P., et al. 1975. Mammals of the world. Third ed. (J.L. Paradiso, ed.) John Hopkins Univ. Press, Baltimore, 2:6451500. Willner, G.R., J.A. Chapman, and D. Pursley. 1979. Reproduction, physiological responses, food habits, and abundance of nutria on Maryland marshes. Wildl. Monogr., 65:41-43. Contributing editor of this account was Clinton Smith.