THE FAMILY AS CAREGIVER: A Group Psychoeducation Model for Schizophrenia

advertisement

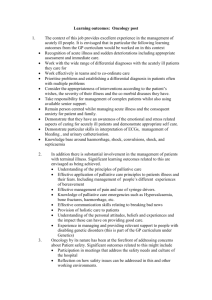

American Journal of Onhopsvchimry, 68(1), January 1998 THE FAMILY AS CAREGIVER: A Group Psychoeducation Model for Schizophrenia Carol S. North, M.D., David E. Pollio, Ph.D., Byron Sachar, M.S.W., Barry Hong, Ph.D., Keith Isenberg, M.D., Gina Bufe, Ph.D., R.N. A professionally led multifamily psychoeducation program for families with a schizophrenic member was designed according to participating families' reported concerns. The families provided information on their problems, needs, coping, and requirements from the program. They expressed more concern about "negative " symptoms of schizophrenia (e.g., social withdrawal) than about positive ones (e.g., hallucinations). Participants' overall positive response to the program is discussed in terms of further development of a multifamily psychoeducation model with family-generated content. R ecent scientific advances in medical - and drug treatment have demonstrable relevance for psychosocial management as a necessary component of care for individuals with severe mental illness. In the mental health sector, dwindling sources of funding have shifted the responsibility for patient care into the community. Families must shoulder many aspects of care for their seriously mentally ill family members, even though they lack special training, knowledge, or access to sufficient professional support. In this environment, a psychoeducational approach to training families for their new role has begun to appear in the clinical literature. This approach is a well-established concept, but relatively ill-defined (Hatfield, 1988). Drawing from Walsh's (1992) defi- nition, psychoeducation groups may be characterized for present purposes as having specified duration, closed membership, and facilitation by one or more trained leaders. Their purpose is to educate members about the illness and give emotional support, but not to provide formal psychotherapy. In the growing literature on family psychoeducation, a number of investigations have described multifamily psychoeducation programs for families with a mentally ill member (Anderson, Reiss, & Hogarty, 1986; Barrowclough & Tarrier, 1987; Doane, Goldstein, Miklowitz, & Falloon, 1986; Falloon et al, 1982; Falloon et al., 1985; Falloon, McGill, Boyd, & Pederson, 1987; Hogarty et ai, 1986; Hogarty, Anderson, & Reiss, 1987; Leff, Kuipers, Ber- A revised version of a paper submitted to the Journal in February 1996. Authors are al: Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, (North, Hong, Isenberg) and George Warren Brown School of Social Work (Pollio), Washington University St. Louis; and in private practice, Centerville, Mass. (Bufe). Byron Sachar, formerly of Barnes-Jewish Hospital, St. Louis, is deceased © 1998 American Orthopsychiatric Association, Inc. 39 40 FAMILY PSYCHOEDUCATIONAL GROUPS kowitz, Eberlein-Vries, & Sturgeon, 1982; Leff, Kuipers, Berkowitz, & Sturgeon, 1985; Leffet al, 1988; Leffet al, 1990; Levene, Newman, & Jeffries, 1989; McFarlane et al, 1995; Tarrier et al., 1988; Tarrier et al., 1989). McFarlane's group documented a cost-effectiveness ratio of $34 of inpatient costs saved for every dollar spent on multifamily psychoeducational treatment. In published reports, the majority of such programs have focused on reducing "expressed emotion" in families, choosing it as a major outcome variable. All reports of professional psychoeducation programs show a content based on predetermined problems identified by the professionals who designed the programs. None of the programs seems to have been designed for a flexibility that would allow changes in program content to match needs identified by the families who are members of the group. That the response of the mental health professional community to families' unmet needs is too slow and insufficient is suggested by the recent development of a family-designed, structured psychoeducation project, the Vermont Journey of Hope program (Burland, 1992), affiliated with the National Alliance for the Mentally 111. The program was set up to deal with problems and concerns of families caring for a mentally ill member from the families' perspective. The existence of such a program implies mat professionally developed family psychoeducation programs have lost sight of the valuable resource represented by families (Hatfield, 1979) for developing the content of family psychoeducation materials. This article presents die methods and exploratory findings from a pilot study of a program for training families as caregivers. It was part of a multifamily group psychoeducation program for families with a member suffering from schizophrenia. The content of the program was tailored in re- sponse to the express needs of the families participating in each group. METHOD Family Workshops Over a two-year period, four one-day public workshops for families with a schizophrenic member were held at the Washington University Medical Center. The workshops were formed to introduce the process of educating families about schizophrenia and to recruit families for a multiple-family group program. Recruitment. Participants for the workshops were recruited from the inpatient psychiatry services at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, from a mailing to all members of the St. Louis Metropolitan Alliance for the Mentally 111 (AMI), and by word-of-mouth via contacts by project staff. Sample. A total of 56 individuals from 34 families participated in the four workshops: eight individuals from four families were in the first workshop, 16 from 11 families in the second, 19 from 10 families in the third, and 13 individuals from nine families in the fourth. Women constituted 53% of participants, and only one of the families was from a minority group (African-American). Program. The program presented at the workshops consisted of didactic presentations on the history of schizophrenia, the illness's symptoms and diagnostic criteria, its causes (drawing from neurochemistry and genetics), and relevant medications, as well as an interactive discussion of problem solving techniques. Measures. At each workshop, participants completed the North-Sachar Family Life Questionnaire (N-SFLQ), a self-report instrument designed for and piloted in mis study.* It contains 11 questions (each with a range of one to five degrees of effect) intended to elicit information about family members' perceived ability to manage the illness and related crises, knowledge about •Information on the questionnaire is available onrequestfromfirstauthor. NORTH ETAL the illness, disruptions to family life, ability to set and achieve behavioral expectations for and to communicate with the ill member, guilt feelings, number of hospital admissions and hospital days in the past year, and number of days lost from work due to the illness. At the end of the workshop, families completed a satisfaction questionnaire, also designed for this study, about the workshop. They were then invited to join a family group for ongoing meetings to extend over at least one year. Those families that participated in the group meetings were again administered the N-SFLQ at the end of the first year. Multiple Family Groups From these workshops, two family groups were started, in which ill family members were also invited to participate. The first group began meeting in August 1993 with eight families; one of these dropped out in the second month, after poor attendance, while another dropped out in the eighth month, after sporadic attendance. This group consisted of 16 individuals at the start and 12 at the end, and included the ill member in three of the families. A second group of five families with eight individuals, including the ill member from two of the families, began in January 1994 but terminated in the fourth month, after the untimely death of a project leader. Inclusion criteria for the family groups required only that the identified ill family member have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, with or without comorbid disorders. Treatment status of the ill family member might be inpatient, outpatient, involuntary commitment to a forensic facility in another state, or not in treatment. The family groups met for 90 minutes, on two evenings per month during the first year and once every three months during the second year. Groups were facilitated by two leaders, one from a psychiatric/nursing background and the other from a family therapy/social work background, providing 41 an interdisciplinary team with broad coverage of professional expertise. At the first family group session, members were asked to list their main difficulties and concerns. The reported problems were compiled into a list that was returned to the families for ranking in order of severity; the investigators then sorted these rankings into a master list using a Q-sort procedure. Thus, each family group arrived at a problem list customized to its own needs (see TABLE 1 for the list generated by the first group). Subsequent sessions were each devoted to a single topic identified by the group, and dealt with in descending order of importance. These identified problems provided the content and order of all the family group sessions during the first year's program. The structure of the ongoing family meetings was developed through modification of McFarlane's group methods (McFarlane et al, 1991). For the first 15-20 minutes of each session, families shared their recent experiences and brought the group up to date on their progress and problems. If didactic material on the meeting's topic was available, a 15-20-minute lecture was presented on related research knowledge, sometimes by an expert invited for the purpose (e.g., a social services expert on ways to gain access to services). Table 1 FAMILIES' RANKED PROBLEM LIST 1. Negative symptoms (esp. amotivation and social withdrawal) 2. How members can be supportive of ill member 3. Communication with ill member 4. Social skills 5. Relapse 6 Medications and side effects 7. Hallucinations and delusions 8 Getting along with other family members; how to support one another 9. Insight and denial; treatment resistance; compliance 10. Recognizing and dealing with feelings (ill member's andfamHy's) 11. Obtaining and managing medical care 12. Community resources 13. Hope and hopelessness 14. Spirituality 15 WeUness 42 FAMILY PSYCHOEDUCATIONAL GROUPS Companion reading material in the form of families were instructed to consult the supfive popular self-help books on schizo- plemental literature as preparation for the phrenia and serious mental illness (Art- next session. At the beginning of each meetdreasen, 1984; North, 1987; Torrey, 1995; ing's didactic section, they were asked Walsh, 1987; Woolis, 1992) was made avail-what they had learned from their reading, able. A 20-minute discussion followed in and it became evident that the self-help which families described manifestations at books (and, indeed, the self-help literature home of the problem under discussion. Mem- in general) contained little or no informabers then participated in 20 minutes of tion on many issues—insight, amotivation, "brainstorming" about ways of dealing spirituality—about which the group memwith the situation, and the group leaders bers were seeking practical help. helped stimulate them to think of new ways Lists collected from these and later famof managing problems. Shared ideas were ily groups are being accrued on an ongoing jotted on easels for all to view, and families basis to form a database of family manifeswere encouraged to record the information tations of problems and of creative probin personal notebooks (in the team's expe- lem solving strategies from group brainrience, members often referred back to storming sessions. A list generated by one these notes when questions arose about of the first family group sessions is shown contents of earlier sessions). in TABLE 2. At the end of each session, the topic for the next session was announced. Some topics required two or three sessions, as determined during the group meetings whenever the amount of material generated became too great to be covered in one session. When a new topic was announced, In some group sessions, special exercises such as relaxation and role playing helped members learn coping skills and problem solving techniques. For example, family members were given a demonstration of what it feels like to hear voices: while one group member tried to give complicated di- Table 2 SELECTED ITEMS GENERATED FROM DISCUSSIONS ABOUT FEELINGS III Member's Feelings Like a freak, the 'ill person" Burden on family Anger at illness/wortd/God/famity/ttoctors; Why me? Lonely, isolated Guilt -What did I do to get this?" Sadness, grief, sorrow Shame—hiding out at home Hypersensitivity ("as if under a microscope') Happy times, glad for doing well Feel loved and cared for Lack of feelings/unable to express feelings Family's Feelings Anger at iHness/wwM/GodrtamBy/doctors/patient; "Dont know who to get angry with/Why me?" Lonely, isolated, alone Guilt f D i d I cause this/Was I insensitive/Did I abandon when in need/Am I doing enough?") Resentment of ill member (especially siblings) Happy times, glad for patient doing weH Fee) burdened Embarrassment, shame, hiding out at home Fears: f u t u r e * r r w r t e r t flehavfcx/suWdenitolence/ harm to iH member/the unknown/getting the Mness (siblings) Sadness, grief, sorrow, despair Apprehension: "What happens after I'm g o n e r Possible Solutions for III Member's Feelings Sometimes it may help to ignore feelings—to a point Distract yourself with activities Take good care of yourself Ventilate Get space and time away Do things you enjoy Forgive yourself Solutions for Family's Feelings Ignore feelings (mostly your own)—to a point EmpattHze, discuss, communicate Ventilate, verbalize Avoid assumptions (e.g. HI members silence may not be anger) Avoid probing too directly (e.g., ask "What's up,' not "What ate you thinking; Drop what you are doing and listen when ill member wants to talk Acknowledge iff member's feeHngs Give self and W member space Give encouragement Figure out what you need, then say it Have hope NORTH ET AL rections to another, three people stood behind the member who was talking and enacted "voices." 43 nificance (one-sided paired /-test, /T=.O57). No other significant differences were found in analysis of the data. Contrary to expectations, the main conRESULTS cerns identified by the families were not Data obtained at the workshops from the the "positive" symptoms of psychosis (e.g., N-SFLQ determined the level of partici- hallucinations, delusions, violent outbursts, pants' knowledge about the illness before suicidality) but the "negative" ones (e.g., joining the program. Though none reported social withdrawal, lack of communication, excellent knowledge, all indicated some: poor social skills, decreased motivation, 43% good, 52% fair, and 5% not good. Mem- excessive sleeping, poor hygiene and perbers reported illness-related disruptions to sonal habits). the family constantly (5%), frequently Feedback from members during the one(24%), occasionally (38%), infrequently year group program and at its end indicated (29%), and never (5%). They reported their that they found both the content of the lecability to deal effectively with illness-re- tures and the group discussions and brainlated crises as excellent (0%), good (36%), storming sessions quite helpful. Members fair (45%), not very good (14%), and poor frequently commented that they had tried (5%). Mean number of hospitalizations for some of the strategies generated at previthe ill family member was 1.9 (SD=2.7), ous meetings and found them extremely and mean number of days hospitalized in useful, or that they had discovered new the last year was 84 (SD=157). It should be elaborations of the techniques. For examnoted that workshop participants who did ple, after a discussion of "triangulation" in not opt to join the family groups reported family relationships, one member returned 45 (S£>=86) hospitalized days in the pre- to report that she had resolved triangulation ceding year. Although a nonsignificant problems of communication in her family trend, this difference suggests that the by having the two family members congroups may have attracted some families cerned talk directly to each other rather with more severely ill members. than snagging a third member as a commuThe satisfaction questionnaire adminis- nication conduit. At later meetings, several tered at the end of each workshop revealed members reported that this idea had proved that 86% of participants found the work- very helpful to diem, also. Group members indicated appreciation shop experience either extremely helpful (66%) or moderately so (20%). Specifical- for the leaders' approach to them as partly, 66% found the workshop moderately or ners in the caregiving process, rather man extremely helpful in coping better with the as part of the pathology. A member who illness, 84% in sharing with other families, had been a leader of a family-sponsored and 79% in hearing other families' stories. group program (Burland, 1992) remarked A common observation was that families on the advantages of professional leadership in maintaining a productive, positive wanted more time for sharing and talking. The N-SFLQ wasre-administeredto par- focus at the present group's sessions. Families reported that while it was usuticipating families at the end of the first year of family group sessions. Only one ally helpful to have their ill member preoutcome measure had sufficient numerical sent at the meetings, there were times when range to provide comparisons: the number they would have felt more free to discuss of days hospitalized was reduced from 84 material in their absence. They suggested (SD=157) in the year before the group pro- mat the ill members and other family memgram to 76 (SZ>=162) in the year spanning bers split into separate subgroups for some the program, a trend toward statistical sig- activities. Over the course of the program, 44 FAMILY PSYCHOEDUCATIONAL GROUPS in addition to learning and developing problem-solving strategies, families in the groups bonded with one another; they reported this as one of the most valuable aspects of the group experience, hot least because they learned from one another, as well as from the professionals. The benefits experienced by the families who completed the first group program led them to schedule regular meetings under their own auspices between the scheduled quarterly, professionally facilitated meetings of the second year. Their suggestions for future groups were that they should allow even more time for sharing, and give more help maneuvering social service systems for assistance with the illness. Group members also reported continuing frustration with the ebbs and tides of their family member's illness, encountering false hope and hopelessness, and an ongoing struggle with the chronicity of the illness. positive symptoms because the former are more likely to be overlooked in treatment and less likely to be eradicated by the medications. The results of this pilot study, while encouraging, were limited, largely due to the small sample size. The reduction in hospital days was modest in clinical terms, but it can represent considerable savings in cost of treatment. Comparison with a control group is necessary to determine whether this reduction was due to the intervention or to extraneous factors. However, it was consistent with the findings of McFarlane and colleagues (1995), and provides additional support for the validity of the multifamily psychoeducation model. Families completing the one-year family group program reported an intense group cohesion as one of the most positive aspects of their group experience. This bonding may have benefited from the families' active role in determining program content and developing group solutions to mutual DISCUSSION The utility of multifamiiy psychoeduca- problems. It is a model that provides an tion groups in the management of schizo- ideal forum for development of new stratephrenia seems evident from the findings of gies and techniques by group members in this pilot study, which confirms those of an emotionally supported setting, and it other research (Anderson et al, 1986; Bar- seems likely that the major outcome in rowclough & Tarrier, 1987; Doane et al., studies of multifamiiy psychoeducation pro1986; Falloon et al, 1987; Hogarty et al., grams will be such direct benefits to fami1986;LeffetaL, 1990; Leveneetal., 1989; lies. It is also possible, as has been postuMcFarlane et al., 1995; Tarrier et al., 1989).lated in other studies (McFarlane et al., The families in this study provided a great 1995; Moller & Murphy, 1997), that endeal of information on their problems and hanced family satisfaction and function reneeds, how they cope with the illness, and sulting from family programs may indihow a psychoeducation program can help rectly improve outcomes for patients. diem. Data collected at the beginning of the The greater number of days spent in hosproject suggests that these families per- pital by ill members of those families who ceived themselves as having insufficient participated in the groups suggests selfknowledge and skills to manage the illness selection of families with members who effectively. were more ill. Alternatively, these may Specific problem areas in which the fam- have been families who were more inclined ilies needed help were also identified in the to get help, both from hospitalization and present study. The primacy ofnegative symp- from family psychoeducation. It is not postoms on die families' problem lists sug- sible to clarify such relationships with the gests a need for for greater focus on this present data, bat they could have a substanissue. It is possible that negative symptoms tial impact on issues of recruitment to famcreate more problems in families than do ily psychoeducation groups. NORTH ET AL 45 family treatment on the affective climate of families of schizophrenics. British Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 279-287. Falloon, I.R.H., Boyd, J.L., McGill, C.W., Williamson, M., Razani, J., Moss, H.B., Gilderman, A.M., & Simpson, G.M. (1985). Family management in the prevention of morbidity of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42, 887-896 Falloon, I.R.H., Boyd, J.L., McGili, C.W., Razani, J., Moss, H.B., & Gilderman, A.M. (1982) Family management in the prevention of exacerbations of schizophrenia: A controlled study. New England Journal of Medicine, 306, 1437-1440 Falloon, I.R.H., McGill, C.W., Boyd, J.L., & Pederson, J. (1987). Family management in the prevention of morbidity of schizophrenia: Social outcome of a two-year longitudinal study. Psychological Medicine, 17, 59-66 Hatfield, A.B. (1979) The family as partner in the treatment of mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 30, 338-340. Hatfield, A.B. (1988). Issues in psychoeducation for families of the mentally ill International Journal of Mental Health, 17, 48-64. Hogarty, G.E., Anderson, CM., & Reiss, D.J. (1987). Family psychoeducation, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in schizophrenia: The long and short of it. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 23, 12-13. Hogarty, G.E., Anderson, CM., Reiss, D.J., Komblith, S.J., Greenwaid, C.P., Javna, CD., & Madonia, M.J. (1986). Family psychoeducation, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43, 633-642. Leff, J.P., Berkowitz, R., Shavit, N., Strachan, A., Glass, I., & Vaughn, C. (1988). A trial of family therapy v. a relatives' group for schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 153, 58-66. Leff, J.P., Berkowitz, R., Shavit, N., Strachan, A., Glass, I., & Vaughn, C. (1990). A trial of family therapy v. a relatives' group for schizophrenia. Two-year follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 571-577. Leff, J., Kuipers, L., Berkowitz, R., Eberlein-Vries, R., & Sturgeon, D. (1982). A controlled trial of social intervention in the families of schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 141, REFERENCES 121-134. Anderson, CM., Reiss, D.J., Hogarty, G.E. (1986). Schizophrenia and the family A practitioner's Leff, J., Kuipers, L., Berkowitz, R., & Sturgeon, D. (1985). A controlled trial of social intervention in guide to psychoeducation and management. New the families of schizophrenic patients: Two-year York: Guilford Press. follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry, 146, Andreasen, N.C. (1984). The broken brain: The bio594-600. logical revolution in psychiatry. New York: Levene, J.E., Newman, F., & Jeffries, J.J. (1989). FoHarper & Row. cal family therapy outcome study I: Patient and Barrowclough, C , & Tarrier, N. (1987). A behavioral family functioning. Canadian Journal of Psychiafamily intervention with a schizophrenic patient: try, 34,641-647. A case study. Behavioral Psychotherapy, 15, McFarlane, W.R., Lukens, E., Link, B., Dushay, R., 252-271. Deakins, S.A., Newmark, M., Dunne, E.J., Horen, Buriand, J.C., Mayeux, D.M., & Gai, D.(1992). JourB., & Toran, J. (1995). Multiple-family groups and ney of hope family education and support. Baton psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophreRouge, LA: Alliance for the Mentally III. nia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52,679-687. Dome, I.A., Goldstein, M.J., Miktowitz, D.J., & Falloon, I.R.H. (1986). The impact of individual and McFarlane, W.R., Deakins, S.M., Gingerich, S.L., The project described in this article was the pilot for a model training program seeking to help families become more effective primary caregivers. The possibility of reaching clear conclusions about the model's efficacy is therefore is limited. Future work on this model must include minority-sensitive recruitment methods, replication and further development using a larger and more representative sample, new program content with additional modules for family groups that can address other concerns and problems, specification of relevant outcome measures, and the testing of outcomes on these measures using comparison populations. This project had the advantage of contribution from many experts—professionals with academic and clinical knowledge of schizophrenia, and the families who spend their lives immersed in the illness. Allowing the program's content to be flexible to the needs of the families in a professionally led group means an ability to tailor such content to specific family groups and their particular issues. Further, the flexibility of this model should lead to increased program participation and yield maximal benefits for each family group. Finally, this program provides a means of accumulating family-oriented education materials that can be organized into a program replicable in medically underserved communities, where programs with defined structure and content are needed. 46 FAMILY PSYCHOEDUCATIONAL GROUPS Dunne, E., Horen, B., & Newmark, M. (1991). Multiple-family Psychoeducalional Group Treatment Manual. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute. North, C.S. (1987). Welcome, silence. New York: Simon & Schuster. Moller, M.D., & Murphy, M.F. (1997) The Three Rs Rehabilitation Program: A preventive approach for the management of relapse symptoms associated with psychiatric diagnoses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 20,42-48. Tarrier, N., Barrowclough, C , Vaughn, C , Bamrah, J.S., Porceddu, K., Watts, S., & Freeman, H. (1988). The community management of schizophrenia: A controlled trial of a behavioral intervention with families to reduce relapse. British Journal ofPsychiatry, 153,532-542. Tarrier, N., Barrowclough, C, Vaughn, C, Bamrah, J.S., Porceddu, K., Watts, S., & Freeman, H. (1989). Community management of schizophrenia: A two-year follow-up of a behavioral intervention with families. British Journal of Psychiatry, 154,625-628. Torrey, E.F. (1995). Surviving schizophrenia: A family manual. New York: Harper & Row. Walsh, J. (1987). The family education and support group: A family psychoeducatkmal aftercare prugiaiii. Psychosodal Rehabilitation Journal, 10,51-61. Walsh J. (1992). Methods of psychoeducational program evaluation in mental health settings. Patient Education and Counseling, 19,205-218. Woolis, R. (1992). When someone you love has a mental illness: A handbookforfamily, friends, and caregivers. New York: Tarcher/Putnam. Forreprints:Carol S. North, MX)., Department of Psychuaiy, School of Medicine, Washington University. 4940 Children's Place, St. Louis, MO 63110