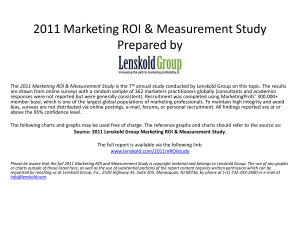

INFLUENCE OF PRE AND POST TESTING ON RETURN ON INVESTMENT

advertisement