26: 461–473 (2005) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/mde.1230

advertisement

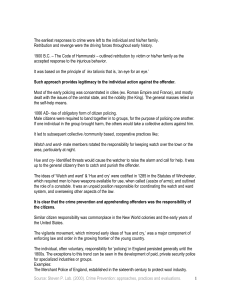

MANAGERIAL AND DECISION ECONOMICS Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/mde.1230 Economies of Scale and Market Power in Policing Lawrence Southwick Jr.*,y,z School of Management, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA The objective of this paper is to use a simultaneous equations method for estimating police production and demand to determine whether or not there are economies of scale in policing. In addition, the effect of market power on productivity, using the Herfindahl–Hirschmann Index, is to be measured. The estimation yields the result that there are diseconomies of scale with respect to the amount of crime beyond about 22 000 people in the policing jurisdiction and diseconomies of scale in numbers of police beyond about 36 000 people. Efficiency is also reduced where there is greater market power. This is conjectured to be the public sector equivalent of taking market power profits. Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. INTRODUCTION An important issue in local government services is their efficiency. It is often argued that larger governments are needed to ensure that economies of scale and thus greater efficiency are realized. As should other enterprises, local governments ought to be concerned about measuring the efficiency of their activities. While their major concern is often with ensuring the provision of some service, the cost of that service needs to be kept in mind as well. The local government can usually raise more money through taxation in order to continue to provide the desired set of services, but the pot of money is not unlimited and the overall well-being of the citizen-taxpayer should more appropriately be the objective of the elected officials. *Correspondence to: School of Management, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260, USA. E-mail: ls5@buffalo.edu y University Research Scholar, University at Buffalo, and Comptroller (retired), Town of Amherst, NY (pop. 116,000). z I appreciate several useful comments from an anonymous reviewer. Neither organization nor any reviewer is responsible for any of the comments expressed herein. Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. It is certainly possible to contract out services in order to achieve economies of scale. For example, many municipalities contract out their garbage collection services. A very large supplier can service several municipalities so, if there are economies of scale, they may be achieved through this mechanism. This can be a substitute for producing the service in-house. An example in policing is the city of Lakewood, California. As do several nearby cities, it contracts with the Los Angeles County police for the various desired policing services. An alternate contractor for many cities in that area is the City of Los Angeles. Also keeping prices in check is the ability of the local government to choose to produce the service on its own.1 In addition, it is possible to contract out parts of the policing activity, particularly support services (see Chaiken and Chaiken, 1987). The objective of this paper is to analyze local governments which choose to produce policing services on their own. This is true of most local governments of even modest size. In particular, the state of New York will be the focus of this study in order to provide a consistency over the legal system and laws. Because most produce as well as 462 L. SOUTHWICK JR. provide policing services, the question of scale economies is very important. It leads to higher or lower tax costs, depending on the size of the municipality. Frequently, it is suggested that communities, by merging, would have lower costs for policing. It is alleged that this would come about through elimination of duplicate layers of management. If there are, in fact, economies of scale, savings could well be the result of such mergers. On the other hand, suppose (as one example) that the managerial span of control is fixed. Then, the bureaucracy will be larger as the size of the police force increases and there are likely to be diseconomies of scale. The result of mergers then would be an increase in costs or a reduction in the level of service. The question of which effect appears to dominate is a major reason for this paper. It is desired to know whether there are economies or diseconomies of scale or whether there is an optimal size. In addition, we shall look at the question of whether market power affects costs. Certainly, in the private sector, prices tend to be higher in cases where firms have more market power. Governments, of course, do not make profits. It is more likely that they would use their market power to reduce efforts towards efficiency and would thus increase costs for their constituents. It is also possible that the market power on the production side would allow lower prices to be paid to providers. Again, the dominant effect of these is to be found empirically. Benson (1998, Chapter 3) argues that governments which do not face much competition are likely to raise their constituents’ costs. This is also similar to Niskanen’s (1968, 1971) argument that bureaucracies attempt to increase their budgets and that competition can be used to keep them in line. Wyckoff (1988, 1990) argues that slack, rather than budget size, can be an objective of the bureaucrat, but either results in an efficiency reduction. Benson (1995) gives an excellent review of how bureaucrats may well pursue objectives other than those desired by their employers, with the result that inefficiency increases. For the police, the usual objective is the reduction of crime.2 There are traffic control objectives and service objectives as well, but the focus here will be on crime as the leading measure of success or failure by the police. Inasmuch as there are several different types of crimes, it is Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. desirable to create a single measure of crime to be used for this measurement.3 Further, since prevention of crime is the primary objective rather than the apprehension of criminals, it will be desirable to estimate the amount of crime that there would be absent the police. At the least, we want to know how the number of police utilized affects the amount of crime. Of course, the police, by apprehending criminals, give a disincentive to commit crimes. Corman et al. (1987) find that arrests do give this result. Viscusi (1986) also finds that deterrence is an important effect. There are many additional studies which also show this effect. Police departments can allocate their resources devoted to preventing crime in a number of ways. However, we would infer from the choices made that the allocation equates the ratio of the marginal disutility of each crime to the marginal crime prevention effect of the resources devoted to preventing that crime. This is an optimal allocation procedure. It takes into account the effectiveness in preventing each crime as well as the dislike the community has for or harm the community receives or perceives it receives from that type of crime. Generally, we would expect that communities would decide that the more serious crimes provide greater disutility. However, the relative levels of disutility may well vary across communities. The result is that one community may spend more effort on preventing robberies while another spends more effort on preventing aggravated assaults. Presumably, the marginal effort in preventing one robbery is about equal to the marginal effort in preventing two aggravated assaults, based on the numbers actually occurring, at least if the average cost of prevention equals the marginal value of a crime prevented.4 PRIOR RESEARCH A number of papers have been written which are germane to the topic of economies of scale. They have been done from a number of methodological points of view, but their general conclusion tends to be that there are diseconomies of scale.5 As an example, Beaton (1974) finds economies of scale only for cities below 2000 population and diseconomies above that. Ostrom and Parks (1973) summarize a number of earlier studies, all of which Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) 463 ECONOMIES OF SCALE IN POLICING show positive relationships between per capita costs and community size. They went on to study how citizens felt about their police services and found that smaller departments resulted in more public satisfaction with the police. Walzer (1972) found that per capita expenditures were strongly positively correlated with city size. Gyimah-Brempong (1987) found diseconomies in cities larger than 25 000–50 000 population. In another paper (Gyimah-Brempong, 1989), he found no economies of scale. Davis and Hayes (1993) also found diseconomies of scale. Drake and Simper (2002) claim economies of scale. However, their results seem to suggest economies for smaller cities and diseconomies for larger cities. These studies typically use cost as their measure and do not consider the effects on crime. At first look, a counter to that generalization is by Hirsch et al. (1975, 1976). They find that the elasticity of crime with respect to population is about 1.01, not significantly different from one. They also find, without using simultaneous equations, that having more police results in reduced crime. Inasmuch as larger cities tend to have more police per capita, this would imply that there are increasing costs to crime prevention for larger cities. Ostrom and Whitaker (1973) looked at the effect of the size of the community on crime and found that smaller communities immediately outside and adjacent to very similar communities within a large city experienced less crime and that the residents felt safer in the smaller communities. Glaeser and Sacerdote (1999) argue that cities provide better pecuniary returns for criminals due to greater density and more potential victims. Further, they note that cities are less likely to apprehend criminals. They find the elasticity of crime rates with respect to city size to be about 0.12. An earlier study, by Christianson and Sachs (1980), used survey data to argue that larger governments are better. Of course, an objective measure like crime is a better measure. A review article by Brynes and Dollery (2002), primarily interested in Australia and general government expenditures, but also reviewing other papers, found that, out of six papers on police economies, two found U-shaped curves, one found no scale effect, and three found diseconomies of scale. In these studies, it was typically the case that costs were computed as dependent on size. In this study, a simultaneous equations approach, incorporating both demand and production equations Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. will be utilized. There have been no studies of which I am aware that have used the market power question in analyzing police efficiency. MODEL The usual method of determining economies of scale in the public sector makes the implicit or explicit assumption that a homogeneous output is to be produced. Further, this output is to be produced in the same amount across communities. This is at variance with the true state of affairs where communities deliberately choose different levels of service in accord with their choice of the market segment to be served. It can readily be observed that the ratio of police to population, even of similarly sized communities, varies substantially. In addition to choice, there are a number of factors which change the propensity of the people in a community to commit crimes. For example, poverty, broken homes, density, and racial characteristics are often cited indicators. A number of these factors are correlated, so only a few need to be included in an empirical model, but any appropriate method needs to include some such effects. The variables chosen will also proxy for the others not included due to their high correlations. The model will incorporate two simultaneous equations, production and demand. The former is the production of safety while the latter is the demand for policing services. As a result of these equations, both crime and police are endogenous. Each of these variables is dependent on other exogenous variables as well. Exogenous variables which appear in both equations will include population and a measure of market power. Market power is included to measure the potential profit or waste due to a lack of competition. While private sector firms can use market power to gain profits, not for profit organizations can only use their market power for inefficiency. Azzam and Rosenbaum (2001) find, using the cement industry, that, while greater efficiency affects price, market power is actually a greater factor. For the production function, (1) Crime=f (police, density, percent non-white, population, HH) where HH refers to the Herfindahl–Hirschmann Index of market power. The effect of Police on Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) 464 L. SOUTHWICK JR. Crime should be negative while Density and Percent Non-White should have a positive effect. Density causes more interpersonal interactions and the percent non-white represents the group most likely to be victimized by crime. The effects of Population and HH are to be determined. For the demand function, (2) Police=f (crime, assets, unit cost, population, HH) where assets are the taxable property value and unit cost is the cost to the community of a unit of policing (essentially the wage rate). Crime and assets (wealth) should be expected to positively affect the number of police. The unit cost (wage) should have a negative effect. While there is no a priori reason for them to affect the quantity demanded, population and HH are included to see if there is an effect. MEASURING CRIME There are a variety of crimes which may be committed, varying in severity. We will include here only those which have direct victims. Some are more common than are others. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) keeps track of seven of these and reports on them annually. As Maltz (1975) argues, the use of crime as the measure of (lack of) police success implicitly assumes that the same proportion of actual crimes is reported in each community. It seems likely, however, that those communities which are less successful in preventing crime, typically the larger communities, will have a lower proportion reported. This will tend to produce a spurious economy of scale. Of course, if the differential effect is small, the bias will also be small. The FBI’s Index Crimes include, in decreasing order of severity, Murder, Rape, Robbery, Aggravated Assault, Burglary, Larceny, and Motor Vehicle Theft. The first four involve violent confrontation between individuals while the latter three are usually non-confrontational and tend to be for commercial purposes. Of course, Robbery is also primarily for commercial purposes, although it may be committed as part of one of the other crimes. When a crime falls potentially into more than one of these categories, the police typically choose the most serious of the charges as the type of crime. Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. The FBI has published annual reports of the seven index crimes for each community in New York State which provides the data to the FBI. The State of New York is chosen because the laws under which each community operates with respect to apprehension and punishment for these crimes are uniform across the State.6 That does not necessarily mean that the application of the laws is uniform but, rather, that it is as uniform as uniform laws can make them. Judges may vary and juries obviously do so as well. If one jurisdiction is more lenient, it may encourage more crime in that community as compared to others which treat criminals more severely. In New York, the court involved in the adjudication of these crimes usually has jurisdiction over several counties. The prosecutors are from a single county. Police in towns, villages, cities, and counties usually make the arrests, although the State Police also make some arrests. In order to estimate the desired functions, it is necessary to create an index of crimes for each year for each community. Crime, in this measure, will be reduced to a single variable from the seven listed above. In order to create an index across these crimes, it is necessary to realize that the numbers of the different types of crimes reported can be expected to vary by orders of magnitudes. In 2000, the US had about 15 500 murders, 90 200 rapes, 408 000 robberies, 911 000 aggravated assaults, 2 050 000 burglaries, 6 966 000 larcenies, and 1 165 000 motor vehicles stolen.7 If we simply sum these, as the FBI does, it will effectively overweight the three non-violent crimes in terms of their importance. In the following analysis, an averaging method will be used which adjusts for the different numbers. In this, the averages for each year will be computed of each crime across the municipalities in the study and the percentage each municipality has of that average will be used as the measure of the amount of that type of crime for that locality. Then, the average of each community’s percentages will be taken across the index crimes to give a single figure measuring the relative crime level for that community.8 Implicitly, this rates each crime type as equal in terms of the relative effect on the overall average. Thus, for example, a single murder is likely to affect a community’s average by considerably more than a single robbery or aggravated assault. It will take a decrease of several of the less important crimes Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) ECONOMIES OF SCALE IN POLICING to offset an increase of one murder. The effect is to treat one murder as approximately equal in harm to 5.8 rapes, 26.3 robberies, 58.8 aggravated assaults, 132.3 burglaries, 449.4 larcenies, or 75.2 auto thefts. VARIABLE DEFINITIONS AND MEASURES The next step is to estimate Equations (1) and (2) by a two stage least squares process (2SLS). This will be done using data on New York State Police departments. A number of these serve more than one community or only serve part of a community because another police department serves the rest of the community. Thus, it is necessary to gather the data for Population and any population related variables for only the area covered by the relevant Police department. Because the census data are available both for Towns and for Villages, it is possible to include only those Villages in a Town Police Department for which policing is actually done by the Town Department.9 For the Police departments covered by this study, contracting out is generally a minor factor and will not affect the data substantially. The most recent data available are for the years 1995 through 2000. From the numbers of people in the 1990 and 2000 census counts in each community, the population figures for each year are computed by an interpolation process. That is, in 1997, for example, 30 percent weighting is given to the 1990 figures and 70 percent weighting to the 2000 figures. The percentage non-white is computed analogously; the 1990 and 2000 figures for whites and non-whites are interpolated as well. In the data gathered annually by the New York State Comptroller’s Office,10 there are figures for the area of the municipality each year as well as financial figures on spending by various categories. The former is divided into the population to compute the density.11 The spending on Police is used to compute the cost per Police officer or per Police employee.12 In addition, the full value of taxable property in the community is used to compute an Assets or wealth variable. This is, of course, done on a per capita basis. In the spending on Police, over the entire data set used, which does not include New York City, the spending on personnel averaged 93.4 percent of all spending on Police. That implies an extremely low capital/labor ratio and might well Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 465 offer some improvements in efficiency with the use of more capital.13 The analysis of that issue, however, is beyond the scope of this study. For our purposes, policing may be thought of as almost entirely a function of the amount of labor. The estimation is done with linear functions, except that population is quadratic so as to ascertain whether there is an optimal size. Because the variables are normalized, the additional variable is 1/population. Thus, the equations to be estimated are (3) C ¼ a0 þ a1 D þ a2 NW þ a3 P þa4 POP þ a5 =POP þ a6 HH. (4) P ¼ b0 þ b1 C þ b2 W þ b3 A þb4 POP þ b5 =POP þ b6 HH. The data are for 150 communities and consist of 669 observations over the 6 year time period. Because some of the communities have incomplete data on some variables, the actual number of observations is less than that for particular estimations. The definitions of the variables to be used are as follows: a. C4 or C7=crime=average of percentage crime rate is of average for all communities for that year. Computed respectively for four violent crimes and for all seven index crimes. b. POLPOP or PERPOP=police=number of police divided by population in thousands. Alternatively, the number of Police employees divided by population in thousands. c. DENSITY=population per square mile. d. NW=non-white=percent of the population which is non-white in the given year. Keep in mind that this represents the likelihood of victimization. e. W=WPOL or WPER=wage rate=real (inflation adjusted) expenditures for police personnel, divided by the number of police. Alternatively, divided by the number of police personnel as appropriate for the equation. f. ASSETS=assets (wealth)=real (inflation adjusted) full property value divided by the population. g. POP=population=total population protected by the particular police department. h. 1/POP=inverse of population, added to make the equation quadratic. Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) 466 L. SOUTHWICK JR. i. HH=Herfindahl–Hirschman Index=based on numbers of police hired by all municipalities in a county, even if the municipality is not in the data set. The value ranges for these variables are given in Table 1. The highest crime community has a crime rate about ten times the lowest, using the seven index crimes. The violent crimes range upwards from zero to six times the average. Both the police per 1000 population and the police personnel (including non-sworn employees) also have a very wide range. The population ranges from 6200 (although the FBI wants to collect crime data only from communities over 10 000, it apparently gets some from smaller places) to a bit over 300 000. (New York City is not included because of missing data as well as because it is so large as to be substantially different from other municipalities.) This gives a good range for economies of scale computation. Non-white percentages range from 0.8 to 74.3. The HH Index for Counties ranges from 825 to 6969. This is measured over the numbers of Police. Table 1. Because there are more than 450 police departments with the numbers of police available, this gives a more accurate measure of the HH Index. The average HH value is 2786, well above the level at which the US Justice Department almost automatically challenges mergers in the private sector. Table 2 gives the correlations across the variables. The two measures of crime, C4 and C7, are correlated at the 0.98 level. Other than that, the highest correlation of crime is with percent nonwhite, at about 0.70. This is because non-whites are more likely to be crime victims.14 The crime rate is correlated with population at about the 0.61 level. The two measures of police per 1000 population are also correlated with each other at the 0.98 level. The only other high correlation of police is with crime at about the 0.50 level. The personnel expenditure measures per police officer or per police employee are correlated at the 0.70 level. Thus, they may represent different philosophies about how to go about performing the function or may represent a substitution of other workers for police if police salaries get too high.15 Other than those mentioned, the correlations Variable Descriptions Variable Mean Std. dev. Minimum Maximum Cases C4 C7 POLPOP PERPOP PCTNW DENSITY ASSETS WPOL WPER HH POP 0.974 0.982 1.966 2.291 0.138 3152 63 232 88 589 75 208 2786 34 965 1.146 0.881 0.757 0.871 0.140 3259 60 217 33 766 18 893 1591 41 907 0.000 0.054 0.049 0.088 0.008 142 14 429 3171 2384 825 6202 6.324 5.253 3.935 4.771 0.743 16 887 517 303 736 362 147 272 6969 310 412 663 663 619 619 663 663 662 618 618 663 663 Table 2. C4 C7 POLPOP PERPOP PCTNW DENSITY ASSETS WPOL WPER HH POP Correlation Matrix C4 C7 POLPOP PERPOP PCTNW Density Assets WPOL WPER HH POP 1.00 0.98 0.49 0.50 0.71 0.48 0.28 0.05 0.05 0.04 0.56 0.98 1.00 0.53 0.55 0.70 0.48 0.26 0.06 0.07 0.01 0.62 0.49 0.53 1.00 0.98 0.45 0.43 0.21 0.02 0.18 0.09 0.24 0.50 0.55 0.98 1.00 0.47 0.44 0.22 0.05 0.14 0.05 0.27 0.71 0.70 0.45 0.47 1.00 0.60 0.09 0.16 0.22 0.24 0.44 0.48 0.48 0.43 0.44 0.60 1.00 0.21 0.18 0.31 0.08 0.30 0.28 0.26 0.21 0.22 0.09 0.21 1.00 0.24 0.37 0.03 0.13 0.05 0.06 0.02 0.05 0.16 0.18 0.24 1.00 0.71 0.01 0.03 0.05 0.07 0.18 0.14 0.22 0.31 0.37 0.71 1.00 0.03 0.02 0.04 0.01 0.09 0.05 0.24 0.08 0.03 0.01 0.03 1.00 0.03 0.56 0.62 0.24 0.27 0.44 0.30 0.13 0.03 0.02 0.03 1.00 Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) 467 ECONOMIES OF SCALE IN POLICING are low enough to effectively remove the problem of colinearity. It is interesting that the HH Index has a near zero correlation with population. Apparently, as a county’s population increases, the number of police departments also increases apace. ESTIMATION RESULTS Two stage least squares regressions are next run using the two equations in four combinations, C4 or C7 and Police/1000 Population or Police Personnel/1000 Population. The regression results are shown in Table 3. The upper half of the table shows the results for the production equation while the lower half shows the results for the demand equation. Each column represents one of the systems of equations with the production equation in the top matching the demand equation below it. In the four production function estimates, all the variables are significant at the 5 percent level, except density in the seven index crimes case where it is still significant at the 10 percent level. Most of the coefficients are significant at the one percent level. In the demand equation estimates, crime and assets are highly significant. Wages, the HH Index, and 1/Population are not significant. Population is significant at the 5 percent level, except in the 4 crimes/personnel case where it is only significant at the 10 percent level. These results are much as expected. The production function has crime positively related to percent non-white, density, population, population inverse, and the HH Index and negatively Table 3. Regression Results Production function Constant POP PCTNW DENSITY POLPOP C4 POL 7.27E-02 (0.31) 1.08E-05 (9.46) 5.9047 (13.69) 4.00E-05 (2.43) 0.5044 (3.76) C7 POL 9.77E-02 (0.59) 9.62E-06 (11.87) 4.1542 (13.59) 2.28E-05 (1.95) 0.2793 (2.93) PERPOP HH POP1 8.31E-05 (3.45) 7137.13 (4.01) 7.46E-05 (4.37) 5114.87 (4.05) POLPOP 1.2263 (9.83) 1.87E-06 (2.00) 0.5202 (13.06) POLPOP 1.0986 (9.02) 3.28E-06 (3.45) C4 PER 2.79E-02 (0.13) 1.09E-05 (9.64) 5.9384 (13.77) 3.46E-05 (2.22) C7 PER 4.42E-02 (0.28) 9.60E-06 (12.10) 4.1340 (13.64) 1.86E-05 (1.70) 0.4121 (3.72) 9.42E-05 (3.99) 6670.36 (3.88) 0.2092 (2.68) 8.06E-05 (4.86) 4785.58 (3.96) PERPOP 1.1959 (7.18) 1.89E-06 (1.79) 0.6106 (13.61) PERPOP 0.9911 (6.15) 3.53E-06 (3.32) Demand function Constant POP C4 C7 ASSETS WPOL 5.33E-06 (11.75) 6.79E-07 (0.91) 0.7157 (13.78) 5.07E-06 (11.90) 3.39E-07 (0.47) WPER HH POP1 2.20E-05 (1.43) 1717.63 (1.47) Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 3.15E-05 (2.15) 1573.50 (1.42) 6.14E-06 (11.40) 0.8383 (14.57) 5.74E-06 (11.47) 1.68E-06 (1.05) 3.94E-06 (0.23) 1341.82 (1.01) 2.92E-06 (1.94) 1.46E-05 (0.88) 1224.85 (0.98) Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) 468 L. SOUTHWICK JR. related to police. The demand function has police increasing with assets and crime and decreasing with population. The next step is to use the system of equations to estimate average elasticities with respect to the exogenous variables. This is done in Table 4. The effect on crime of population averages an elasticity of 0.19 while the effect on police averages an elasticity of 0.04. From Table 3, the direct effect of population on police was negative. However, because crime increases with population, the indirect effect on police is sufficiently positive to outweigh the negative direct effect. Market power also has an effect on both crime and police, with average elasticities, respectively, of 0.21 and 0.04. It appears that as citizens have fewer alternatives, this leads both to more crime and, as crime increases, to more police. The increase in market power results not in increased profits, but rather in more waste. The average elasticities for percent non-white for crime and for police are, respectively, 0.57 and 0.17. Again, as crime increases, the number of police increases due to demand for their services. Average elasticities for density for crime and for police are, respectively, 0.08 and 0.02. These are similar to, although smaller than, the percent nonwhite effects. Assets (property value per capita) has elasticities of –0.10 and 0.14 on crime and police. This is due to the causal effect of wealth on police and the causal effect of police against crime. Wages (personnel expenditure on police officers or on police personnel) have little effect, corresponding with the intuition that demand for police is inelastic and, therefore, there is little effect on Table 4. crime. It is possible that higher wages also induce a higher quality level of police, although we have no data on this. Because a formula quadratic in population was used, it is possible to look at the coefficients to see if there is an optimal sized community. If we assume that all the variables other than crime, police, and population are set to the average values, we can compute how the levels of police and crime respond to changes in population. The results for minima on both crime and police are shown in Table 5. The averages of these over the four equations estimated are populations of 22 350 for crime and 35 988 for police.16 At population levels below 22 350, both crime and police are higher than they could be at a larger community size. This implies that, unless there are some additional people nearby who could be incorporated into the community, consideration should be given to mergers. Liner and McGregor (2002) argue for an optimal amount of annexation, trading off short run savings for longer run administrative inefficiencies, although not specifically for police. At population levels above about 36 000, both crime and police are also higher than Table 5. Population For Minima C4 POL C7 POL C4 PER C7 PER Average Crime Police 23 097 21 066 22 912 22 328 22 350 38 003 38 133 33 757 34 058 35 988 Average Elasticities C4 POL C7 POL C4 PER C7 PER AVERAGE Of crime WRT POP PCTNW DENSITY ASSETS WPOL/WPER HH 0.1849 0.6554 0.1038 0.1388 0.0248 0.2153 0.1957 0.4800 0.0616 0.0761 0.0071 0.1984 0.1872 0.6648 0.0906 0.1317 0.0429 0.2210 0.1975 0.4876 0.0514 0.0658 0.0399 0.2031 0.1914 0.5720 0.0768 0.1031 0.0127 0.2095 Of police WRT POP PCTNW DENSITY ASSETS WPOL/WPER HH 0.0325 0.1680 0.0266 0.1356 0.0243 0.0240 0.0336 0.1711 0.0220 0.1357 0.0127 0.0260 0.0439 0.1716 0.0234 0.1351 0.0440 0.0522 0.0449 0.1747 0.0184 0.1344 0.0816 0.0550 0.0387 0.1713 0.0226 0.1352 0.0221 0.0393 Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) 469 ECONOMIES OF SCALE IN POLICING they could be if the community were smaller. Consideration should be given in such a case to lowering the size through splitting the community into smaller separate communities. Between the population sizes of 22 350 and 36 000, the community is experiencing a rise in relative crime rates but a fall in police per capita as population increases. This implies that there is a cost to having the greater crime but a savings to having a relatively smaller police force. This is, therefore, a range within which it is reasonable to stay, unlike smaller or larger communities. The choice with a tradeoff is what makes it rational, unlike the cases of populations under 22 350 and over 36 000 where both crime and police and their associated costs increase. These results are also shown in Figure 1. There are two curves. The lower is for the production function and shows averages for the crime rates, assuming the demographic characteristics are at the averages. It reaches a minimum at the population of about 22 350. The upper line is for police per 1000 population where, again, the demographic variables are assumed to be at their average values. It reaches its minimum at a population of about 36 000. At the population Figure 1. Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. size for a minimum level of crime, the result of a doubling of population is an increase of about 15 percent in crime, other things being equal. It is not always possible to set the size of a community with precision. People decide to move in or out according to the mix of taxes paid and services received, as compared with other alternative communities. However, it is certainly possible to determine geographic boundaries as well as setting a maximum density. This can result in a population upper limit. A lower limit is harder to create inasmuch as people may choose smaller or rural communities for other reasons. Of course, an equivalent to a merger could be an overlay district with responsibility only for policing in more than one community. CONCLUSIONS There appear to be some economies of scale in policing, up to a population size of about 22 350. Beyond that, there are diseconomies of scale. However, there are reduced numbers of police per capita up to a population of about 36 000 and increased numbers thereafter. Thus, the potentially efficient sizes of communities with respect to crime and cost may range from about 22 350 – 36 000. In that range, there is a cost/crime tradeoff which may be made. As the population is reduced below 22 350, costs and crime both rise and, as the population increases above 36 000, costs and crime both rise. Between those sizes, a population increase results in crime increasing while policing costs decrease. Another important result is that increased market power, as measured by the Herfindahl– Hirschmann Index, results in increased crime. A higher degree of market power also increases the size of the police force. This is the first study of which I am aware which looks at this factor in policing. It shows that competition is important both for the effectiveness of municipalities in reducing crime and for keeping costs down. As Crowley (2001) of the Atlantic Institute for Market Studies said, ‘Public sector competition, like private sector competition, is not ‘wasteful’, but is a healthy discipline that promotes efficiency, accountability and good service. Such competition, where it has been introduced into local government, has transformed it for the better’. Frech and Mobley (1995) also find in hospitals Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) 470 L. SOUTHWICK JR. that there are both scale and concentration effects, in that case offsetting. Claggett and Ferrier (1998) found a similar result that municipalities tended to overuse inputs relative to cooperatives in electricity distribution. This result is consistent with the theoretical results found by Niskanen (1968, 1971) that more competition helps control waste by bureaucracies. It may be that the higher concentration gives the employee unions more power. In New York State, most police departments are unionized. Contracts are reached with negotiations which, if agreement cannot be reached, are concluded in binding arbitration. Greater concentration may, as Trejo (1991) argues, give the union more power. This may result in less efficiency or greater costs. This is similar to the result found by Captain and Sickles (1997) where greater union power resulted in lowered efficiency in airlines. There is a combination effect of these two factors. Suppose there is a large population in a contiguous area. If the communities within that region are smaller, that will also imply that there are more communities and a greater competitiveness. The HH Index will decrease and that will both reduce crime and reduce costs. The population of the communities will also be smaller and that will reduce both crime and costs. Of course, this assumes that the resulting communities are above about 22 350 population. Let us make up an example to show this combination of effects. Suppose that there are five cities within a county, each with 40 000 people and having the average demographics of all the Table 6. communities within the state. This gives an HH Index of 2000, under the average for New York State. The two equations estimated for the police per capita, using respectively the four index crimes and the seven index crimes, are used and solved for these cities. The results are shown in Table 6. The initial crime level is about 0.85 or 0.88 of the state average and the number of police is about 75 per city, or 373 overall. Now, suppose two of these cities merge. The HH Index increases from 2000 to 2800. Of course, the new combined city now has a population of 80 000. The result is that crimes in the merged city increase by over 40 percent while the number of police per capita increases by about 4.2 percent. There is an effect on the remaining three cities as well. They find crime increasing by over 6 percent with police per capita increasing by less than one percent. Over the whole county, crime increases by about 20 percent and police increase by about 2 percent. The merger is thus costly to both the merging cities and to other cities through the increase in concentration.17 This suggests that non-merging cities have an interest in opposing mergers among their neighbors. Another conclusion which should be drawn is that mergers which are intended to save money should not be done if the resulting community is larger than about 50 000. This follows from the decrease in cost from 25 000 to 36 000 and the increase in cost from 36 000 to 50 000. If the objective is to have low crime, the merger should not be done if the resulting community is larger than about 35 000. This follows from the crime Five City Examplea Before and After two Cities Merge 4 Crimes 7 Crimes Police Crimes Police Crimes Before merger Each city Total/average 74.8 373.8 0.8489 0.8489 74.7 373.4 0.8839 0.8839 After merger New merged city Other cities Total/averageb 155.8 75.3 381.8 1.2189 0.9086 1.0327 155.8 74.7 379.8 1.2420 0.9395 1.0605 Percentage change New merged city Other cities Total/average 4.22% 0.72% 2.12% 43.60% 7.03% 21.66% 4.29% 0.00% 1.72% 40.51% 6.29% 19.98% a b Each city 40 000 pop., average demographics. Weighted average. Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) ECONOMIES OF SCALE IN POLICING decrease from 17 500 to 22 000 and the crime increase from 22 000 to 35 000 and beyond. A typical argument for mergers of municipal police departments is that a layer of management is duplicative and will be eliminated, saving money. The above results, however, contradict this. A more likely result is that increased size results in more needed management due to limitations on span of control. For a given span of control, a larger police department will require more management positions rather than fewer. The effect will be that fewer of the police will be available to directly deal with crime and more will be absorbed as managers. This does not necessarily imply that there cannot be efficiencies through shared services such as training or laboratories. Potentially, these could be provided on a contractual basis by private enterprise or by an overlay government or even with a contract between two or more municipalities. However, this will work toward efficiency only if each user is charged a fair cost and if the provider is able to make a profit with that fair cost below the cost of individual provision of the service. A competitive market in such services with free entry will induce the optimal size organization.18 NOTES 1. Boyne (1998) argues that contracting may result in greater competition and efficiency as well as scale effects but reviews a number of papers which he decides are inconclusive on the issue. Benson (1998, Chapter 2) gives examples of communities which have contracted out their policing services to private firms. He also (Chapter 3) notes several benefits and costs to contracting out. 2. As Benson et al. (1992) point out, increasing police resources devoted to enforcement of drug laws which are not an index crime means frequently that less effort is devoted to the prevention of the index crimes. Further, Benson (1995) argues that bureaucrats may want to pursue non-index crimes more vigorously in order to gain more resources to pursue the index crimes. See also Benson et al. (1998). 3. There are multi-objective methods available as well. For example, Data Envelopment Analysis can be used in such cases. 4. Suppose that the average cost of a crime is equal to the marginal cost, reasonable because crimes have individual victims. Suppose further that the number of crimes of any type is equal to a base number, multiplied by exp(aiPi) where ai is a constant for that crime and Pi is the allocation of policing resources to that crime. Assuming an optimal allocation of policing resources across crimes, it Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 471 can readily be shown that the ratio of the average cost of a particular crime to the average cost of another type of crime is equal to the inverse of the ratio of the number of crimes of each type. This method appears superior to that used by Lynch et al. (2000) and by Lynch et al. (2001) where an attempt is made to estimate the cost of crime by its effect on house prices. While their method is potentially feasible, the actual results are not particularly encouraging. House prices are subject to wide variability across communities due to other influences. Burney (1998) even finds diseconomies of scale in governmental electricity generation using a time series. If a similar analysis is to be performed for a municipality in some other state, the comparison should be made across communities in that state. See Uniform Crime Report 2000, various tables. This is the same measure used by the firm Morgan Quitno of Lawrence, Kansas to compare crime rates across municipalities for the popular media in its annual report, City Crime Rankings, except that Morgan Quitno does not include Larceny. In New York State, Villages may be part of a Town or may have parts of two or more Towns. Each municipality may decide to have a Police department or to contract with another municipality for the service. In many cases, the municipalities are too small to afford a Police department. Numerous Towns and Villages choose to have either the Sheriff’s Department or the State Police provide policing services. See New York State, Office of the State Comptroller, Special Report on Municipal Affairs, for each relevant year. This does introduce some error where the policing area is not exactly the same as the area of the municipality. However, because densities for nearby areas are typically similar, the error is likely to be minor. If there is contracting out for support services, as indicated by Chaiken and Chaiken (1987), the cost will still be counted in the cost of police officers due to this method. However, the number of police personnel may be affected. Based on typical police departments in New York State where contracting out must be negotiated with the police unions, there seems to be little of this done in those departments. Benson (1998) argues that increasing capital results in decreased effectiveness, so the low capital/labor ratio may be appropriate, although this is counter to the effects in other industries. It is also possible that non-whites are more likely to be criminals as well. Further, that variable is likely to be correlated with poverty, lower education, and other factors leading to the commission of crime. As noted by an anonymous referee, low job skills are more likely to exist in the minority community, leading to a lower opportunity cost of being a criminal. Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) 472 L. SOUTHWICK JR. 15. The dispatch function, for example, may be done either by sworn police officers or by civilians, depending on management choices made. 16. It is interesting to note that Giordano (1997) found a similar U-shaped scale function in trucking through survivor analysis; of course, municipalities are not subject to a similar competition. 17. The population numbers have been used in this example to compute the HH Index. However, earlier, the police numbers were used. This implies that this example, in fact, underestimates the adverse effect of the merger. 18. Saal and Parker (2000) found, in another context, that there are diseconomies of scale in government services as well as benefits to privatization. REFERENCES Azzam A, Rosenbaum D. 2001. Differential efficiency, market structure and price. Applied Economics 33(10): 1351ff. Beaton WP. 1974. The determinants of police protection expenditures. National Tax Journal 27(2): 335–349. Benson BL. 1995. Understanding bureaucratic behavior: implications from the public choice literature. Journal of Public Finance and Public Choice 8: 89–117. Benson BL. 1998. To Serve and Protect: Privatization and Community in Criminal Justice. New York University Press: New York. Benson BL, Kim I, Rasmussen DW, Zuehlke TW. 1992. Is property crimes caused by drug use or by drug enforcement policy? Applied Economics 24(7): 679–692. Benson BL, Rasmussen DW, Kim I. 1998. Deterrence and public policy: tradeoffs in the allocation of police resources. International Review of Law and Economics 18: 77–100. Boyne GA. 1998. Bureaucratic theory meets reality: public choice and service contracting in US local government. Public Administration Review 58(6): 474ff. Brynes J, Dollery B. 2002. Do economies of scale exist in Australian local government? A review of the empirical evidence. University of New England Working Paper Series, No. 2002-2, 2002. Burney NA. 1998. Economies of scale and utilization in electricity generation in Kuwait. Applied Economics 30(6): 815ff. Captain PF, Sickles RC. 1997. Competition and market power in the European airline industry: 1976–1990. Managerial and Decision Economics 18: 209–225. Chaiken M, Chaiken J. 1987. Public Policing}Privately Provided. National Institute of Justice, 1987. Washington, DC. Christianson JA, Sachs CE. 1980. The impact of government size and number of administrative units on quality of public services. Administrative Science Quarterly 25(1): 89–101. Claggett ET, Ferrier GD. 1998. The efficiency of TVA power distributors. Managerial and Decision Economics 19: 365–376. Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Corman H, Joyce T, Lovitch N. 1987. Crime, deterrence and the business cycle in New York city: a VAR approach. Review of Economics and Statistics 69(4): 695–700. Crowley BL. 2001. Municipal amalgamations in Atlantic Canada and beyond: why amalgamate? A talk to the Annual Meeting of the BC Municipal Finance Authority, 29 March 2001, Victoria, BC. Davis ML, Hayes K. 1993. The demand for good government. Review of Economics and Statistics 75(1): 148–152. Drake L, Simper R. 2002. X-efficiency and scale economies in policing: a comparative study using the distribution free approach and DEA. Applied Economics 34: 1859–1870. Frech III HE, Mobley LR. 1995. Resolving the impasse on hospital scale economies: a new approach. Applied Economics 27(3): 286–297. Giordano JN. 1997. Returns to scale and market concentration among the largest survivors of deregulation in the US trucking industry. Applied Economics 29(1): 101–110. Glaeser EL, Sacerdote B. 1999. Why is there more crime in cities? Journal of Political Economy 107(6 part 2): S225–S228. Gyimah-Brempong G. 1987. Economies of scale in municipal police departments: the case of Florida. Review of Economics and Statistics 69(2): 352–356. Gyimah-Brempong G. 1989. Production of public safety: are socioeconomic characteristics of local communities important factors? Journal of Applied Econometrics 4(1): 57–71. Hirsch WZ, Sonenblum S, Chapman JI. 1975. Crime prevention, the police production function, and budgeting. Public Finance 2: 197–215. Hirsch WZ, Sonenblum S, Chapman JI. 1976. Crime prevention and the police production function. In Public and Urban Economics, Grieson RE (ed.). Lexington Books: Lexington, MA; 247–265. Liner GH, McGregor RR. 2002. Optimal annexation. Applied Economics 34(12): 1477–1485. Lynch AK, Clear T, Rasmussen DW. 2000. Modelling the cost of crime. In The Economic Dimensions of Crime, Fielding NG, Clarke A, Witt R (eds). St. Martins Press: NY; 226–237. Lynch AK, Rasmussen DW, Moore DL. 2001. Measuring the impact of crime on house prices. Applied Economics 13: 2001. Maltz MD. 1975. Measures of effectiveness for crime reduction programs. Operations Research 23(3): 452–474. Niskanen WA. 1968. The peculiar economics of bureaucracy. American Economic Review 58(2): 293–305. Niskanen WA. 1971. Bureaucracy and Representative Government. Aldine: Chicago. Ostrom E, Parks RB. 1973. Suburban police departments: too many and too small? In The Urbanization of the Suburbs, Masotti LH, Hadden JK (eds), vol. 7. Sage Urban Affairs Annual Review 367–402. Sage: Beverly Hills, CA and London. Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005) ECONOMIES OF SCALE IN POLICING Ostrom E, Whitaker G. 1973. Does community control of police make a difference? Some preliminary findings. American Journal of Political Science 17(1): 48–76. Saal DS, Parker D. 2000. The impact of privatization and regulation on the water and sewerage industry in England and Wales: a translog cost function model. Managerial and Decision Economics 21: 253–268. Trejo SJ. 1991. Public sector unions and municipal employment. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 45(1): 166–180. Copyright # 2005 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 473 Viscusi WK. 1986. The risks and rewards of criminal activity: a comprehensive test of criminal deterrence. Journal of Labor Economics 4(3, part 1): 317–340. Walzer N. 1972. Economies of scale and municipal police services: the Illinois experience. Review of Economics and Statistics LIV(4): 431–438. Wyckoff PG. 1988. Bureaucracy and the ‘publicness’ of local public goods. Public Choice 56: 271–284. Wyckoff PG. 1990. The simple analytics of slackmaximizing bureaucracy. Public Choice 67: 35–47. Manage. Decis. Econ. 26: 461–473 (2005)