Poetry Selections - Center for Humanist Inquiries

advertisement

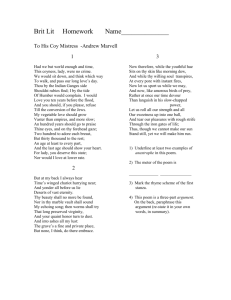

Week 1: Shakespeare SONNET 116 Let me not to the marriage of true minds Admit impediments. Love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds, Or bends with the remover to remove: O no; it is an ever-fixed mark, That looks on tempests, and is never shaken; It is the star to every wandering bark, Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken. Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks Within his bending sickle's compass come; Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, But bears it out even to the edge of doom. If this be error and upon me proved, I never writ, nor no man ever loved. Week 2:To His Coy Mistress (Andrew Marvell) Had we but world enough and time, This coyness, lady, were no crime. We would sit down, and think which way To walk, and pass our long love’s day. Thou by the Indian Ganges’ side Shouldst rubies find; I by the tide Of Humber would complain. I would Love you ten years before the flood, And you should, if you please, refuse Till the conversion of the Jews. My vegetable love should grow Vaster than empires and more slow; An hundred years should go to praise Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze; Two hundred to adore each breast, But thirty thousand to the rest; An age at least to every part, And the last age should show your heart. For, lady, you deserve this state, Nor would I love at lower rate. But at my back I always hear Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near; And yonder all before us lie Deserts of vast eternity. Thy beauty shall no more be found; Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound My echoing song; then worms shall try That long-preserved virginity, And your quaint honour turn to dust, And into ashes all my lust; The grave’s a fine and private place, But none, I think, do there embrace. Now therefore, while the youthful hue Sits on thy skin like morning dew, And while thy willing soul transpires At every pore with instant fires, Now let us sport us while we may, And now, like amorous birds of prey, Rather at once our time devour Than languish in his slow-chapped power. Let us roll all our strength and all Our sweetness up into one ball, And tear our pleasures with rough strife Through the iron gates of life: Thus, though we cannot make our sun Stand still, yet we will make him run. Week 3: Anne Sexton—Love Poems The Touch For months my hand had been sealed off in a tin box. Nothing was there but subway railings. Perhaps it is bruised, I thought, and that is why they have locked it up. But when I looked in it lay there quietly. You could tell time by this, I thought, like a clock, by its five knuckles and the thin underground veins. It lay there like an unconscious woman fed by tubes she knew not of. The hand had collapsed, a small wood pigeon that had gone into seclusion. I turned it over and the palm was old, its lines traced like fine needlepoint and stitched up into the fingers. It was fat and soft and blind in places. Nothing but vulnerable. And all this is metaphor. An ordinary hand—just lonely for something to touch that touches back. The dog won’t do it. Her tail wags in the swamp for a frog. I’m no better than a case of dog food. She owns her own hunger. My sisters won’t do it. They live in school except for buttons and tears running down like lemonade. My father won’t do it. he comes with the house and even at night he lives in a machine made by my mother and well oiled by his job, his job. The trouble is that I’d let my gestures freeze. The trouble was not in the kitchen or the tulips but only in my head, my head. Then all this became history. Your hand found mine. Life rushed to my fingertips like a blood clot. Oh, my carpenter, the fingers are rebuilt. They dance with yours. They dance in the attic and in Vienna. My hand is alive all over America. Not even death will stop it, death shedding her blood. Nothing will stop it, for this is the kingdom and the kingdom come. The Ballad of the Lonely Masturbator The end of the affair is always death. She’s my workshop. Slippery eye, out of the tribe of myself my breath finds you gone. I horrify those who stand by. I am fed. At night, alone, I marry the bed. Finger to finger, now she’s mine. She’s not too far. She’s my encounter. I beat her like a bell. I recline in the bower where you used to mount her. You borrowed me on the flowered spread. At night, alone, I marry the bed. Take for instance this night, my love, that every single couple puts together with a joint overturning, beneath, above, the abundant two on sponge and feather, kneeling and pushing, head to head. At night, alone, I marry the bed. I break out of my body this way, an annoying miracle. Could I put the dream market on display? I am spread out. I crucify. My little plum is what you said. At night, alone, I marry the bed. Then my black-eyed rival came. The lady of water, rising on the beach, a piano at her fingertips, shame on her lips and a flute’s speech. And I was the knock-kneed broom instead. At night, alone, I marry the bed. She took you the way a woman takes a bargain dress off the rack and I broke the way a stone breaks. I give back your books and fishing tack. Today’s paper says that you are wed. At night, alone, I marry the bed. The boys and girls are one tonight. They unbutton blouses. They unzip flies. They take off shoes. They turn off the light. The glimmering creatures are full of lies. They are eating each other. They are overfed. Week 4: Rumi The intellectual is always showing off, the lover is always getting lost. The intellectual runs away. afraid of drowning; the whole business of love is to drown in the sea. Intellectuals plan their repose; lovers are ashamed to rest. The lover is always alone. even surrounded by people; like water and oil, he remains apart. The man who goes to the trouble of giving advice to a lover gets nothing. He's mocked by passion. Love is like musk. It attracts attention. Love is a tree, and the lovers are its shade. At night, alone, I marry the bed. Week 5: Adrienne Rich: From 21 Love Poems: I Wherever in this city, screens flicker with pornography, with science-fiction vampires, victimized hirelings bending to the lash, we also have to walk . . . if simply as we walk through the rainsoaked garbage, the tabloid cruelties of our own neighborhoods. We need to grasp our lives inseperable from those rancid dreams, that blurt of metal, those disgraces, and the red begonia perilously flashing from a tenement sill six stories high, or the long-legged young girls playing ball in the junior highschool playground. No one has imagined us. We want to live like trees, sycamores blazing through the sulfuric air, dappled with scars, still exuberantly budding, our animal passion rooted in the city. II I wake up in your bed. I know I have been dreaming. Much earlier, the alarm broke us from each other, you've been at your desk for hours. I know what I dreamed: our friend the poet comes into my room where I've been writing for days, drafts, carbons, poems are scattered everywhere, and I want to show her one poem which is the poem of my life. But I hesitate, and wake. You've kissed my hair to wake me. I dreamed you were a poem, I say, a poem I wanted to show someone . . . and I laugh and fall dreaming again of the desire to show you to everyone I love, to move openly together in the pull of gravity, which is not simple, which carried the feathered grass a long way down the upbreathing air. III Since we're not young, weeks have to do time for years of missing each other. Yet only this odd warp in time tells me we're not young. Did I ever walk the morning streets at twenty, my limbs streaming with a purer joy? did I lean from any window over the city listening for the future as I listened here with nerves tuned for your ring? And you, you move toward me with the same tempo. Your eyes are everlasting, the green spark of the blue-eyed grass of early summer, the green-blue wild cress washed by the spring . At twenty, yes: we thought we'd live forever. At forty-five, I want to know even our limits. I touch you knowing we weren't born tomorrow, and somehow, each of us will help the other live, and somewhere, each of us must help the other die. Week 6: Henri Cole: Gravity and Center I'm sorry I cannot say I love you when you say you love me. The words, like moist fingers, appear before me full of promise but then run away to a narrow black room that is always dark, where they are silent, elegant, like antique gold, devouring the thing I feel. I want the force of attraction to crush the force of repulsion and my inner and outer worlds to pierce one another, like a horse whipped by a man. I don't want words to sever me from reality. I don't want to need them. I want nothing to reveal feeling but feeling—as in freedom, or the knowledge of peace in a realm beyond, or the sound of water poured in a bowl. Week 7: Rainer Maria Rilke—Letters to a Young Poet 7, World Was in the Face of the Beloved Rome, May 14th, 1904, My dear Mr. Kappus, Much time has gone by since I received your last letter. Do not hold that against me; first it was work, then interruptions and finally a poor state of health that again and again kept me from the answer, which (so I wanted it) was to come to you out of quiet and good days. Now I feel somewhat better again (the opening of spring with its mean, fitful changes was very trying here too) and come to greet you, dear Mr. Kappus, and to tell you (which I do with all my heart) one thing and another in reply to your letter, as well as I know how. You see-I have copied your sonnet, because I found that it is lovely and simple and born in the form in which moves with such quiet decorum. It is the best of those of your poems that you have let me read. And now I give you this copy because I know that it is important and full of new experience to come upon a work of one's own again written in a strange hand. Read the lines as though they were someone else's, and you will feel deep within you how much they are your own. It was a pleasure to me to read this sonnet and your letter often; I thank you for both. And you should not let yourself be confused in your solitude by the fact that there is something in you that wants to break out of it. This very wish will help you, if you use it quietly, and deliberately, like a tool, to spread out your solitude over wide country. People have (with the help of conventions) oriented all their solutions toward the easy and towards the easiest side of the easy; but it is clear that we must hold to what is difficult; everything alive holds to it, everything in Nature grows and defends itself in its own way and is characteristically and spontaneously itself, seeks at all costs to be so and against all opposition. We know little, but that we must hold to is difficult is a certainty that will not forsake us; it is good to be solitary; for solitude is difficult; that something is difficult must be a reason the more for us to do it. To love is good, too: love being difficult. For one human being to love another: that is perhaps the most difficult of all our tasks, the ultimate, the last test and proof, the work for which all other work is but preparation. For this reason young people, who are beginners in everything, cannot yet know love: they have to learn it. With their whole being, with all their forces, gathered close about their lonely, timid, upward-beating heart, they must learn to love. But learning-time is always a long, secluded time, and so loving, for a long while ahead and far on into life, is-solitude, intensified and deepened loneness for him who loves. Love is at first not anything that means merging, giving over, and uniting with another (for what would a union be of something unclarified and unfinished, still subordinate-?), It is a high inducement to the individual to ripen, to become something in himself, to become world for himself for another's sake, it is a great exacting claim upon him, something that chooses him out and calls him to vast things. Only in this sense, as the task of working at themselves ("to hearken and to hammer day and night", might young people use the love that is given them. Merging and surrendering and every kind of communion is not for them (who must save and gather for a long, long time still), is the ultimate, is perhaps that for which human lives as yet scarcely suffice. But young people err so often and so grievously in this: that they (in whose nature it lies to have no patience) fling themselves at each other, when love takes possession of them, scatter themselves, just as they are, in all their untidiness, disorder, confusion...And then what? What is life to do to this heap of half-battered existence which they call their communion and which they would gladly call their happiness, if it were possible, and their future? Thus each loses himself for the sake of the other and loses the other and many others that wanted still to come. And loses the expanses and the possibilities, exchanges the approach and flight of gentle, divining things for an unfruitful perplexity out of which nothing can come any more, nothing save a little disgust, disillusionment and poverty, and rescue in one of the many conventions that have been put up in great number like public refuges along this most dangerous road. No realms of human experience is so well provided with conventions as this: lifepreservers of most varied invention, boats and swimming-bladders are here; the social conception has managed to supply shelters of every sort, for, as it was disposed to take love as a pleasure, it had also to give it an easy form, cheap, safe and sure, as public pleasures are. It is true that many young people who love wrongly, that is, simply with abandon and unsolitary (the average will of course always go on doing so), feel the oppressiveness of a failure and want to make the situation in which they have landed viable and fruitful in their own personal way-; for their nature tells them that, less even than all else that is important, can questions of love be solved publicly and according to this or that agreement; that they are questions, intimate questions from one human being to another, which in case demand a new, special, only personal answer-; But how should they; who have already flung themselves together and no longer mark off and distinguish themselves from each other, who therefore no longer possess anything of their own selves, be able to find a way out of themselves, out of the depth of their already shattered solitude? They act out of common helplessness, and then, if, with the best intentions, they try to avoid the convention that occurs to them (say, marriage), they land in the tentacles of some less loud, but equally deadly conventional solution; for then everything far around them isconvention; where people act out of a prematurely fused, turbid communion, every move is convention: every relation to which such entanglement leads has its convention, be it ever so unusual (that is, in the ordinary sense immoral); why, even separation would here be a conventional step, an impersonal chance decision without strength and without fruit. Whoever looks seriously at it finds that neither for death, which is difficult, nor for difficult love has any explanation, any solution, any hint or way yet been discerned; and for these two problems that we carry wrapped up and hand on without opening, it will not be possible to discover any general rule resting in agreement. But in the same measure in which we begin as individuals to put life to the test, we shall, being individuals, meet these great things at closer range. The demands which the difficult work of love makes upon our development are more than life-size, and as beginners we are not up to them, But if we nevertheless hold out and take this love upon us as burden and apprenticeship, instead of losing ourselves in all the light and frivolous play, behind which people have hidden from the most earnest earnestness of their existence-then a little progress and an alleviation will perhaps be perceptible to those who come long after us; that would be much. We are only now just beginning to look upon the relation of one individual person to a second individual objectively and without prejudice, and our attempts to live such associations have no model before them. And yet in the changes brought about by time there is already a good deal that would help our timorous novitiate. The girl and the woman, in their new, their own unfolding, will but in passing be imitators of masculine ways, good and bad, and repeaters of masculine professions. After the uncertainty of such transitions it will become apparent that women were only going through the profusion and the vicissitude of those (often ridiculous) disguises in order to cleanse their own most characteristic nature of the distorting influences of the other sex. Women, in whom life lingers and dwells more immediately, more fruitfully and confidently, must have become fundamentally riper people, more human people, than easygoing man, who is not pulled down below the surface of life by the weight of any fruit of his body, and who, presumptuous and hasty, undervalues what he thinks he loves. This humanity of woman, borne its full time in suffering and humiliation, will come to light when she will have stripped off the conventions of mere femininity in the mutations of her outward status, and those men who do not yet feel it approaching today will be surprised and struck by it. Some day (and for this, particularly in the northern countries, reliable signs are already speaking and shining), some day there will be girls and women whose name will no longer signify merely an opposite of the masculine, but something in itself, something that makes one think, not of any complement and limit, but only of life and existence: the feminine human being. This advance will (at first much against the will of the outstripped men) change the love-experience, which is now full of error, will alter it from the ground up, reshape it into a relation that is meant to be of one human being to another, no longer of man and woman. And this more human love (that will fulfill itself, infinitely considerate and gentle, and kind and clear in binding and releasing) will resemble that which we are preparing with struggle and toil, the love that consists of this, that two solitudes protect and border and salute each other. And this Further: do not believe that great love once enjoined upon you, the boy, was lost; can you say whether great and good desires did not ripen in you at the time, and resolutions by which you are still living today? I believe that love remains so strong and powerful in your memory because it was your first deep being-alone and the first inward work you did on your life.- All good wishes for you, dear Mr . Kappus! Yours: Rainer Maria Rilke World Was in the Face of the Beloved World was in the face of the beloved--, but suddenly it poured out and was gone: world is outside, world can not be grasped. Why didn't I, from the full, beloved face as I raised it to my lips, why didn't I drink world, so near that I couldn't almost taste it? Ah, I drank. Insatiably I drank. But I was filled up also, with too much world, and, drinking, I myself ran over. Translated by Stephen Mitchell Week 8: William Carlos Williams: The Ivy Crown The whole process is a lie, unless, crowned by excess, It break forcefully, one way or another, from its confinement— or find a deeper well. Antony and Cleopatra were right; they have shown the way. I love you or I do not live at all. Daffodil time is past. This is summer, summer! the heart says, and not even the full of it. No doubts are permitted— though they will come and may before our time overwhelm us. We are only mortal but being mortal can defy our fate. We may by an outside chance even win! We do not look to see jonquils and violets come again but there are, still, the roses! Romance has no part in it. The business of love is cruelty which, by our wills, we transform to live together. It has its seasons, for and against, whatever the heart fumbles in the dark to assert toward the end of May. Just as the nature of briars is to tear flesh, I have proceeded through them. Keep the briars out, they say. You cannot live and keep free of briars. Children pick flowers. Let them. Though having them in hand they have no further use for them but leave them crumpled at the curb's edge. At our age the imagination across the sorry facts lifts us to make roses stand before thorns. Sure love is cruel and selfish and totally obtuse— at least, blinded by the light, young love is. But we are older, I to love and you to be loved, we have, no matter how, by our wills survived to keep the jeweled prize always at our finger tips. We will it so and so it is past all accident.