PowerPoint Slides

advertisement

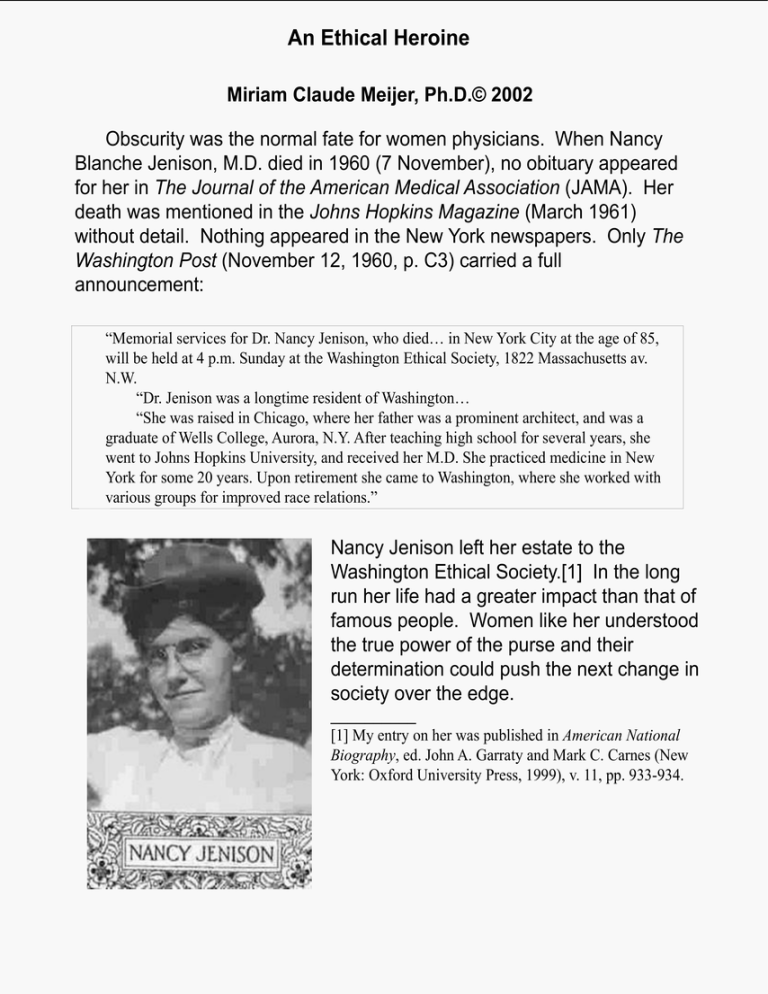

An Ethical Heroine Miriam Claude Meijer, Ph.D.© 2002 Obscurity was the normal fate for women physicians. When Nancy Blanche Jenison, M.D. died in 1960 (7 November), no obituary appeared for her in The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). Her death was mentioned in the Johns Hopkins Magazine (March 1961) without detail. Nothing appeared in the New York newspapers. Only The Washington Post (November 12, 1960, p. C3) carried a full announcement: “Memorial services for Dr. Nancy Jenison, who died… in New York City at the age of 85, will be held at 4 p.m. Sunday at the Washington Ethical Society, 1822 Massachusetts av. N.W. “Dr. Jenison was a longtime resident of Washington… “She was raised in Chicago, where her father was a prominent architect, and was a graduate of Wells College, Aurora, N.Y. After teaching high school for several years, she went to Johns Hopkins University, and received her M.D. She practiced medicine in New York for some 20 years. Upon retirement she came to Washington, where she worked with various groups for improved race relations.” Nancy Jenison left her estate to the Washington Ethical Society.[1] In the long run her life had a greater impact than that of famous people. Women like her understood the true power of the purse and their determination could push the next change in society over the edge. __________ [1] My entry on her was published in American National Biography, ed. John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), v. 11, pp. 933-934. Industrialization The period around Nancy’s birth was a critical one in America’s history. During the decades before the Civil War, Americans experienced the greatest development of industrial production and urbanization. The once integral home economy was dismantled, and, from this time forward, many divisions were created: work versus leisure, the domestic versus the occupational, and public versus private life. The U.S. Census of 1860 indicated that only 10.2% of women were employed outside of the home. A larger proportion of the female population was placed at the margins of production than at any time before or since. This fact gave foundation to the doctrine of “the separate spheres,” a segregation of the masculine and feminine spheres: separate but complementary. Men were the “bread-earners” and women the “bread-givers.” The “commanding” male would fight, politick, and scrape for his income, while the wife would oversee the world of “human ties,” particularly within the family. “True womanhood” and the cult of domesticity made the women’s stable home base an anchor to the young men who faced uncertain economic prospects and constant moving. The ideal of the modern family created by the middle class was small in size, emotionally intense, and female-supervised. Feminism Ironically, motherhood could be used to justify activities outside of the home. A new phenomenon—the women’s college—developed after the Civil War. Educators tried to elevate the domestic occupation from drudgery to a noble profession with female education. Domestic science included the “physics” of ventilation, the “chemistry” of home remedies, the “aesthetics” of furniture, the “architecture” of domestic space, and the “psychology” of child care. The intention was to assure the endurance of domesticity, but women’s schooling had the opposite effect. Educated middle-class women used their learning and newly acquired self-confidence to assert themselves in public. While the businessmen of the Gilded Age were building their trusts and monopolies, the women of the upper and middle classes were creating equally impressive national organizations with their own ideas about society. Operating through settlement houses, women’s clubs, and welfare agencies, women developed the reformist critique of industrial America. In the Progressive Movement, women used the cult of domesticity—not to separate themselves off from the world of men—but to participate in selected aspects of social and economic life. Chicago Nancy Jenison’s mother, Caroline M. Spooner (b. 11 April 1851), “who lived in Chicago through all her active life, was passionately interested in education, the future of woman, the welfare of the Negro, and in America.”[2] Nancy’s father, Edward Spencer Jenison (b. 23 January 18147) was an architect who helped rebuild Chicago after the Great Fire. The Chicago City Directories revealed that he later became a civil engineer. Both parents came from Ohio but spent their lives in Chicago. Nancy was born on 8 July, 1876 in Republic, Ohio, where her mother retreated to give birth (Nancy had an older sister and a younger brother). Called “Nannie” in her childhood, Nancy was confirmed at All Souls church, attended Greenwood Avenue School, and graduated from Hyde Park High School in 1893. During Nancy’s lifetime, the role of women and their opportunities changed radically. In 1890 only 25% of college graduates were female (3,000), but, by 1900 40% of them were female! Between 1890 and 1920 the number of professional women increased 226%, almost triple the rate of male advancement. By 1920, 5% of the nation’s doctors were women, as were 1.4% of the lawyers and judges, and 30% of the college presidents, professors, and instructors.[3] __________ [2] Text on a plaque of Nancy Jenison in the Washington Ethical Society. [3] Mary P. Ryan, Womanhood in America: From Colonial Times to the Present (New York: Franklin Watts, 1979): 138-141. Wells College Nancy attended Wells College, a small women’s college in Aurora, New York, from 1894 to 1898. She was the Artistic Editor of the literary college publication and a member of the college Settlement Association. At age 22 (1898) she graduated cum laude with a B.A. in English. In the Wells tradition of planting an ivy to commemorate her class graduation, Nancy delivered the Ivy Day Oration. We can confirm that she successfully fulfilled the Wells College ideals that she described: “So we have had to learn to be self-dependent. Every task has been valuable only as it has strengthened our abilities and made us capable of greater things. There is always work to be done, some of it easy, some of it difficult. The world cannot stand still. Each generation must take up the work of its predecessor. …”[4] Although a number of America’s early woman physicians grew up or were educated in this area of New York, famous as the “burned over district” for its unorthodox ideas, at this time there is no indication that Nancy was thinking about medical school. __________ [4] N. B. J., “Ivy Oration,” Cardinal (1898): 147-151. School Teacher The alternative to the comparative idleness of the native-born middle class daughters between puberty and marriage (about six years) was school teaching. For several years Nancy taught high school in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; found it most trying, and gave it up.[5] The profession that attracted more women, other than teaching, was medicine. Female teachers were paid one third that of their male counterparts, whereas the average income of a woman doctor in 1881 was three times that of a male white-collar worker.[6] There were other reasons for women to enter medicine. Medicine meshed personal ambition with ideology perfectly: self-development while helping others. Women physicians could pursue a career and reform society without overstepping too far the bounds of accepted propriety. Known to love children, Nancy must have decided that she could help many more children as a physician than as a teacher or mother. It was also common for female physicians to have a physician in the family already and the brother of Nancy’s mother was a successful Ohio surgeon.[7] __________ [5] A 1906 letter from her sister addressed to Nancy in Milwaukee states: “I’m sorry you’ve had such a hard time.” Madge Jenison papers, 1905-1960, The New York Public Library, Manuscripts & Archives Section. [6] Mary Roth Walsh, “Doctors Wanted: No Women Need Apply:” Sexual Barriers in the Medical Profession, 1835-1977 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977): 184. [7] Henry Kuhn Spooner (1837-1908) was a surgeon in charge of the first division, twentieth army corps, during the Civil War. He became one of the oldest and best known physicians of Seneca County in Ohio. Regina Markell Morantz-Sanchez, Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American Medicine (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985): 93. Baltimore Most important, by 1890, an unprecedented feminist victory had been won: women were to be admitted to an elite medical school. The “Women’s Fund Committee,” founded by four wealthy and capable Baltimore women, endowed half a million dollars to the financially-strapped Johns Hopkins University on the condition that women be admitted to its new School of Medicine on the same terms as men from the day it opened in 1893. Nancy decided to become a doctor sometime between her two periods of graduate study at The University of Chicago. In 1899, she studied philosophy, but, during her second residence, in 1906, she took general inorganic chemistry in preparation for Johns Hopkins University. In 1907 she was admitted to the first-rate coeducational medical school which emphasized research in the basic sciences. Nancy’s late decision—she was 31 years old—was typical for women in medicine because this career choice required a woman to be very strong in character. Nancy became one of seven women in the 1911 class of 90 graduates and about the 67th woman to graduate from Johns Hopkins as a M.D.[8] __________ [8] Female medical students were generally older than their male counterparts. Alan M. Chesney and William H. Howell, The Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine: A Chronicle (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1943-1963), vols. 1-3. New York City Although hospital training was increasingly recognized as essential to a complete medical education, the only American hospital open to female interns was the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. This free clinic had been founded in 1853 by Elizabeth Blackwell (18491910), America’s first woman medical doctor. From 1911 to 1913 Dr. Jenison interned at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children.[9] Some medical women had salaried positions in schools or asylums, but most were in private practice. Dr. Jenison did both. In 1914 she became Clinical Assistant at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children and at the Mount Sinai Dispensary.[10] She was promoted in 1915 to Assistant Attending Physician at the New York Infirmary for Women and Children and from 1917 to 1926 she continued there as Attending Physician. Dr. Jenison published a case of blepharochalasis in a Russian Jewish boy immigrant that she observed from 1912 to 1914.[11] In 1916 Dr. Jenison joined the Cornell University Medical College, first as Assistant Physician, and then also as Clinical Instructor in Medicine, continuing both positions until 1929.[12] From 1916 to 1919 she became also a Sheldon Fellow in Medicine at Cornell. From 1919 until 1921 or 1922 she worked as an Adjunct Assistant Visiting Physician at Bellevue. __________ [9] This clinic exists today as the New York University Downtown Hospital. [10] “Nancy Jennison.” Mount Sinai Hospital annual report 1914. Our thanks to Barbara J. Niss for this information. Levy Library, Mount Sinai Medical Center, 1 Gustave Levy Place, Box 1013, New York City, New York 10029-6574. [11] Nancy Jenison, M.D., “Blepharochalasis,” New York Medical Journal 118 (September 11, 1915): 555-556. [12] Cornell University Medical College Announcements (1916-1930). Our thanks to Adele A. Lerner, Archivist, for this information. New York-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Archives, 1300 York Avenue, New York City, New York 10021-4896. Dr. Nancy Women physicians gravitated to what became “feminine” medical specialties, and Dr. Jenison, likewise, chose pediatrics. Her private practice, where she was affectionately addressed as “Dr. Nancy,” flourished for two decades in New York City. Women doctors favored the cities. A disproportionately large percentage of patients were female and women often preferred a woman doctor. One such patient wrote Dr. Nancy: “When I first met you thro Dr. Wakefield you remember, I thot you the most common sense physician and one of the nicest people I knew.”[13] Dr. Nancy carried a correspondence with many of her patients after they had moved away and received photographs of the children she had treated as they grew up. __________ [13] Letter to Nancy Jenison from Melinda R. Abbot, 5 High Ridge Road, Worcester, Massachusetts. World War I In 1915, the year that the American Medical Association (AMA) finally admitted women as members, a woman surgeon (Dr. Bertha Van Hoosen) founded the American Medical Women’s National Association, which Dr. Nancy joined instead. In 1917 she helped co-author their War Service Committee’s report. “We, the undersigned, offer our services to the Secretary of War as members of the Medical Reserve Corps, to be utilized to the fullest extent for home or foreign service, as indicated after our names, by the United States War Department in the present war. We desire that opportunities for medical service be given to us equal to the opportunities for medical service given to medical men, as members of staffs of base hospitals and otherwise, and that we be given the same rank, title, and pay given to men holding equivalent positions.”[14] However, the short duration of the first World War precluded any meaningful advance for American medical women. Their contribution was limited to the establishment of a number of hospitals in Europe and the use of some 55 women doctors as contract surgeons. These women performed surgery in military hospitals without any military status or benefits such as pensions and most hospitals dropped female interns as soon as the war was over. __________ [14] Nancy Jenison, M.D. co-author, “Report of Work June to October, 1917 War Service Committee of the Medical Women’s National Association,” The Woman’s Medical Journal: A Monthly Journal Published in the Interests of Women Physicians 27 (October 1917): 218-225. Female Professionals Dr. Nancy took advantage of every opportunity that presented itself to her. She traveled a great deal and even studied abroad. She never married. The women born between 1865 and 1874 married later and less frequently than any group before or since. At the turn of the century nearly one in five married women was childless. The trend away from domesticity was most pronounced among educated women. They rejected marriage in favor of meaningful work. In 1920 75% of the female professionals were single.[15] These women liked their freedom and knew how to enjoy themselves. Dr. Nancy, for example, frequented the cultural events of Chicago and New York City. Her personal effects included programs from many museums, operas, and plays. Her sister, Madge C. Jenison (1874-1960), earned recognition in Woman’s Who’s Who of America, was captain 25 Assembly District (N.Y. City) Woman Suffrage Party, co-founded an important book shop, published short stories and a few books, and wrote articles on German Model Housing and Workman’s Insurance.[16] __________ [15] Mary P. Ryan, Womanhood in America: From Colonial Times to the Present (New York: Franklin Watts, 1979): 142. [16] John William Leonard, ed. Woman’s Who’s Who of America: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporary Women of the United States and Canada, 1914-1915 (New York: The American Commonwealth Company, 1976): 429-430. Publishers’ Weekly (March 14, 1960): 41. Publishers’ Weekly (July 4, 1960): 167-168. Who’s Who of American Women: A Biographical Dictionary of Notable Living American Women, vol. 1 (Chicago: Marquis, 1958): 646; vol. 2 (1961-1962): 507. Retirement In 1931 a 55-year-old Dr. Nancy retired from practice to live in the countryside in Bound Brook, New Jersey. In 1939 she visited Guatemala. Her sketchbook indicates a budding interest in anthropology—a field in which female professionals had made great strides. At the age of 66, thanks to the fact that she knew Spanish and French, she studied for a year in Mexico City at the National School of Anthropology. Washington, D.C. In researching her family history she learned that her mother’s greatgrandfather had owned slaves in Maryland. A dramatic incident occurred after her grandfather had moved to Kentucky with his slaves: “Sometimes during their early residence there the colored people planned an uprising and were to kill all their masters and families. They move a curve down the middle of the forehead as a membership sign. An old colored mammy who was of the bunch finally told our grandmother and she hid with her two little children till the disturbance was quelled.”[17] Dr. Nancy moved to Washington, D.C. to work on improving race relations. She was as convinced that African Americans had equal rights with other citizens as she was of women’s rights. __________ [17] Manuscript, Washington Ethical Society Archives. Dr. Beauchamp Most likely she met Dr. George E. Beauchamp (1906-1988), the Leader of the Washington Ethical Society, at civil rights events. She joined the Society in 1950, when she was 74 years old, and George and his wife Catherine became “family” to her. In 1951, when Catherine Beauchamp’s mother died, Dr. Nancy moved into the Beauchamps’ house, and accompanied them, well dressed and prompt, every week downtown to the Ethical Society for the Sunday services. Catherine Beauchamp wrote to me in October about her memories of Dr. Nancy: “I can’t remember how long she lived with us, but long enough for us to adopt her into the family. Every morning she’d come down the backstairs to get a cup of hot water for her tea. Her evening meal was the only meal she ate ‘out.’ A restaurant only a block away provided the main meal unless she took a bus or taxi elsewhere. When possible, of course, I offered her a special dish, sometimes a meal. She was so kind and thoughtful, and very independent!”[18] No longer practicing medicine, except to help poor children in a clinic downtown or to give emergency assistance, Dr. Nancy served the Washington poor neighborhoods and the Ethical Society. __________ [18] Letter from Catherine Beauchamp to Miriam Meijer, October 30, 1997, from Kissimmee, Florida. Ethical Society In 1954 the Society purchased their first Meeting House, realizing George Beauchamp’s dream, at 1822 Massachusetts Avenue, close to Dupont Circle. Knowledgeable about plant nurture, Dr. Nancy took charge of its front lawn, worked regularly on the monthly newsletter, served as a member of the Hospitality Committee, sold souvenirs from her travels to Latin America and Scandinavia at the Society’s “Fairs,” and sold plants after the Sunday services. Dr. Nancy became convinced that the Society should move into a larger building and she began to work toward that end. But since the building, a former family row house, was heavily mortgaged in tens of thousands of dollars, most members thought expansion unlikely. Nevertheless, Dr. Nancy established a building fund to retire the mortgage and sold live plants, shrubs, and ivy cuttings after the Sunday meetings to contribute, slowly but steadily, to this fund. After the Beauchamps retired to Florida in 1957, Dr. Nancy moved downtown to the Washington Fellowship House near the Society. Three years later she returned to New York City to care for her sister Madge. Soon after Madge’s death Dr. Nancy died at 85. Edward L. Ericson, the Leader, conducted a memorial service for her in Washington. Only after the service was it discovered that Dr. Nancy— despite appearances—actually had a fortune! Estate Her last will and testament reflected her life. To Wells College Dr. Nancy bequeathed ten thousand dollars for scholarships to “native American and negro girls” until 1975, then to be used for any girl studying at Wells College. Her gift continues to provide general financial aid for students at Wells College today.[19] The scholarship which her will established at the Johns Hopkins University, where she had already donated her stamp collection, can be found on the Internet: “Dr. Nancy Jenison Scholarship Fund. Through a generous bequest from Dr. Nancy Blanche Jenison, a member of the Class of 1911, a scholarship fund was established in 1963 to provide financial assistance for deserving women medical students.” Otherwise, her entire estate was left to “the Ethical Society where George and Catherine are members.”[20] Dr. Beauchamp decided that her legacy should go into the building fund that Dr. Nancy had created. Once the will was resolved, the bequest paid off the old building, which was then sold to make a down payment on a new larger structure uptown. Thanks to her generosity, the Society could discontinue its dependence, since 1959, on annual Leadership subventions by the American Ethical Union.[21] In 1964 the contemporary Washington Ethical Society building, designed by Cooper th and Auerbach, opened on 16 Street near Kalmia Road in Shepherd Park. __________ [19] Email communication of April 8, 1999. Amy L. Robinson, Acting Director of Development, Pettibone House, Wells College, Aurora, New York 13026. [20] Catherine Weaver Beauchamp, Family Ties and Tales (Daytona Beach, Florida: The Daytona Beach News-Journal, 1989): 162. [21] New York Law Journal. Wednesday, January 15, 1964. L. D. MacIntyre, The Washington Ethical Society 1943-1944—1963-1964: A Story of Its Beginnings and Its Development (Washington, D.C.: The Washington Ethical Society, 1964): 69. A Life Well-lived Nancy Jenison, M.D. had a vision about what was possible for her. She had to go up against everything everybody else thought about what women like her should be doing. She followed her own inclinations, and, thereby in so doing, she pushed history forward. The independence and determination, which had enabled her to become one of the nation’s few female physicians, served her to the end. In her retirement she was motivated to turn her efforts to civil rights. She had learned about her great, great-grandfather owning slaves; she took responsibility for her family and she paid it back. She took a wrong and made it right. Nancy Jenison fulfilled maternal urges without herself having babies. She experienced joy and honor in finding ways of being a woman other than in having babies or even in being a mother. She did not make motherhood the end-all of being female. She nurtured, educated, and cared for (many) others beyond her personal home. Her femininity was channeled into a multitude of directions and she touched the lives of many people. Conclusion While some thought it sad that she was childless, old and solitary with her gardening, sketching, and bird-watching, Dr. Nancy lived exactly as she chose. Her hobbies fit with her scientific training, her frugality permitted the growth of the Washington Ethical Society, and thereby she returned the favor that the Baltimore Women’s Fund Committee had handed her. Nancy Jenison was a woman who lived her personal life in a way that made her life count in social progress, whether it was in teaching, in being a medical doctor, in being active in civil rights, or in nurturing the Ethical Society. At each stage of her life she found some purpose to service. A freethinker devoted to laws fair to women as well as men, to black people as well as white, she found a kindred spirit in Ethical Culture, a movement which had been founded in this country the year of her birth. She invested in the humanistic religion that encouraged members to be ethical catalysts in the community at large. Bibliography Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives. The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. American Medical Directories. Beauchamp, Catherine Weaver. Family Ties and Tales. Daytona Beach, Florida: The Daytona Beach News-Journal, 1989. Burke, William J. and Will D. Howe. American Authors and Books 1640 to the Present Day (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1972): 330. Caplan, Doris Cheveres. Rescued Jenison’s remaining photos, letters, and drawings at the Washington Ethical Society. Chesney, Alan M. and William H. Howell. The Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine: A Chronicle. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1943-1963. Vols. 1-3. Chicago City Directories. Duffy, John. From Humors to Medical Science: A History of American Medicine. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1993. Eckerson, Judith. Communication. October 1, 1997, Woodbridge, Virginia. Ericson, Edward L. Communication. November 8, 1997, Dunedin, Florida. Madge C. Jenison Jenison, Margaret C. “American Girls and American Colleges,” Delineator 73 (April 1909): 561, 621, 623-624. “And Now It Must Be Sold,” Bookman 57 (March 1923): 48-52. “Bookselling as a Profession for Women,” Woman’s Home Companion 49 (June 1922): 26. “Church and Social Unrest,” Outlook 89 (May 16, 1908): 112-114. “A Defense of the Arts and Crafts Movement,” Independent 60 (February 8, 1906): 325-329. Dominance. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1928. “Enter Posey Cotton,” Collier’s National Weekly 51 (September 13, 1913): 5-6, 29. “Germany’s Tramp Workmen: Where the Skilled Craftsman Makes the Grand Tour with Wallet and Working Papers,” Harper’s Weekly 55 (October 14, 1911): 15. “A Hull House Play,” Atlantic Monthly 98 (July 1906): 83-92. Invitation to the Dance. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1929. “Lie,” Harper 118 (January 1909): 212-218. “Militant Moment of Lou Grey,” Harper 131 (November 1915): 895-904. Madge C. Jenison “Patience and Shuffle the Cards,” McClure’s Magazine 44 (January 1914): 28-37. “A Persian Fairy Tale,” The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine 82 (October 1911): 950. “Queer Kinks of Courage,” Delineator 79 (June 1912): 490. Roads: A History. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1948. Gotham Book Mart, 1948 (ISBN: 0910664498). “A Sacrament of the Night, A Story,” Harper 112 (April 1906): 732-738. “Spectator,” Harper 115 (August 1907): 470-480. “State Insurance of Germany,” Harper 119 (October 1909): 727-734. The Sunwise Turn: A Human Comedy of Bookselling. Dutton, 1923, 1951. Booksellers Publishing, Inc., 1993 (ISBN: 1879923068). “Tenements of Berlin,” Harper 118 (February 1909): 359-369. “Three in a Ditch,” New Republic 30 (April 12, 1922): 190-192. “True Believer; Story,” Harper 177 (August 1938): 262-271. “Woman with Yellow Gloves,” Harper’s Monthly Magazine 126 (February 1913): 409-416. “Wrong Man: The Story of Andy Toth, Who Served Twenty Years in Prison for Another’s Crime,” American Magazine 73 (December 1911): 237-245. Jenison, M. C. with A. E. Moran. “Cinderalla Dines,” Everybody’s Magazine 16 (June 1907): 745-751. Bibliography Obituary. Johns Hopkins Magazine (March 1961): 30. Leonard, John William, ed. Woman’s Who’s Who of America: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporary Women of the United States and Canada, 1914-1915 New York: The American Commonwealth Company, 1976. MacIntyre, Carol. Communication. October 8, 1997, Dunedin, Florida. MacIntyre, L. D. The Washington Ethical Society: 1943-1944—19631964: A Story of Its Beginnings and Its Development. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Ethical Society, 1964. Meijer, Miriam Claude. "Nancy B. Jenison, M.D. (1876-1960)," American National Biography, eds. John A. Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (Oxford University Press, 1999), v. 11, pp. 933-934. Morantz-Sanchez, Regina Markell. Sympathy and Science: Women Physicians in American Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. New York Law Journal. Wednesday, January 15, 1964. Packard, Francis R. “Women in Medicine,” History of Medicine in the United States, vol. 2, 1222-1227. New York and London: Hafner Publishing Company, 1963. Bibliography Publishers’ Weekly (March 14, 1960): 41. Publishers’ Weekly (July 4, 1960): 167-168. Ryan, Mary P. Womanhood in America: From Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Franklin Watts, 1979. Sloan, De Villo. "Science and Conscience: The Uses of a Liberal Education," The Express (Spring 2001): 4-6. Starr, Paul. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books, 1982. Turner, Thomas B. Heritage of Excellence: The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, 1914-1947. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974. United States Census: 1880, 1900, 1920. Walsh, Mary Roth. “Doctors Wanted: No Women Need Apply:” Sexual Barriers in the Medical Profession, 1835-1977. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977. Washington Ethical Society Archives. The Washington Post November 12, 1960. Wein, Roberta. “Women’s Colleges and Domesticity, 1875-1918,” History of Education Quarterly 14 (1974): 31-47. Who’s Who of American Women: A Biographical Dictionary of Notable Living American Women, vol. 1 (Chicago: Marquis, 1958): 646; vol. 2 (1961-1962): 507.