Fluorescent Probes in PCR

advertisement

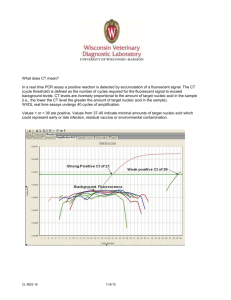

Fluorescent Techniques in PCR Cao jian ping PCR • Amplification of specific gene or gene fragments • Process of PCR 1. Denaturation 2. Annealing 3. Extension • Traditional way to assay the result of PCR: Agarose gel electrophoresis and subsequent staining with ethidium bromide • Drawback: too much time! Fluorescent Techniques • Non-specific assay: Detect through the binding of double-strand DNA specific dyes, these kinds of dyes have essentially no fluorescence of their own and become intensely fluorescent when they bind to nucleic acids. Fluorescent Techniques • Specific assay: Include an additional hybridization to an internal part of the amplified product and detect the PCR product by generating a signal change only when the correct product is amplified left tube contains non-complementary single-stranded oligonucleotide Fig 1. The and the right tube contains complementary single-stranded. The sample concentration in left tube is five times as that in right tube. The were photographed using ASA 400 film. Nicke Svanvik,* Gunnar Westman,† Dongyuan Wang,* and Mikael Kubista*,1.(1999) Effect of oligodeoxyribonucleutides on the Fluorescent Properties of Conjugated Dye • The quenching of fluorophore by guanine It is due to electron donating ability, which permits the charge transfer between the nucleobase and a nearby dye. • Effect of terminal base pair (Table1.) (Table2.) Irina Nazarenko, Rick Pires, Brian Lowe, Mohamad Obaidy and Ayoub Rashtchian. (2002) Table 1. Duplex Fluorescence DS Fluorescence SS 1. . . TC-3’ . . AG-5’ 0.13 2. . . TCA-3’ . . AGT-5’ 1.07 3. . . TCC-3’ . . AGG-5’ 0.27 4. . . TC-3’ . . AGG-5’ 0.61 5. . . TC-3’ . . AGGG-5’ 0.76 6. . . TTAC-3’ . . AATG-5’ 1.06 7. . . TTAAAC-3’ . . AATTTG-5’ 1.80 Table 1. • Duplex1: A labeled olgonucleotide containing a 3’-terminal dC was quenched by 87% upon duplex formation. • Duplex2: addition of a single dA-T base pair to the end of the same duplex completely eliminated the quenching • Duplex4: A 5’-dG overhang on the complementary unlabeled strand provides much less quenching than a dG-dC blunt-end base pair • Duplex5: adding a second dG to the complementary strand to give a two base overhang reduced the quenching effect even more • Duplex6 and duplex7: when the fluorophore was positioned further from the 3’ end, the quenching upon hybridization decreased. Table 2 Oligonucleotide duplex Fluorescence DS Fluorescence SS 5‘-GATGGCTCTTGTTCTCGGTAG-3’ CTACCGAGAACAAGAGCCATC 1.05 5‘-GATGGCTCTTGTTCTCGGTAG-3’ CTACCGAGAACAAGAGCCATC 0.30 The oligonucleotide labeled close to the 3’ end showed substantial quenching upon hybridization, while the oligonucleotide labeled close to the 5’ end exhibited no decrease in fluorescence. Conclusion • The 3’ terminal dG-dC or dC-dG base pair quenches the fluorophore, and this quenching depends on the distance between the fluorophore and the blunt end of duplex. The quenching decreases when the fluorophore is positioned further from 3’ end. • The presence of a dG overhang quenches the fluorescence less efficiently than a blunt end dG-dC or dC-dG base pair. • When located internally in the double strand, the dG-dC base pair does not affect the fluorescence of the nearby dye. • When the dye was positioned within the same sequence context but close to 5’ end, no decrease in fluorescence. Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) • • Dipole– dipole interactions between the two fluorophores. The emission spectrum of donor overlaps the absorption spectrum of acceptor Fluoreophore as donor, quencher as acceptor • The intensity of the fluorescence of the acceptor fluorophore increases,the intensity of the fluorescence of the donor fluorophore decreases. • The distance between donor and acceptor. 1. The transfer efficiency is in proportion to the inverse sixth power of the distance between two emission groups. 2. Effective range: 20-100 A Salvatore A. E. Marras*, Fred Russell Kramer and Sanjay Tyagi(2002) Contact Quenching • The donor and the acceptor are too close. • The intensity of the fluorescence of both the donor fluorophore and the acceptor fluorophore is reduced. • All fluorophores are quenched equally well, no correlation with the emission spectrum of donor and absorption spectrum of acceptor . Fig2. Salvatore A. E. Marras*, Fred Russell Kramer and Sanjay Tyagi (2002) SYBR Green I • • • • An asymmetric cyanine dye Non-specific assay dsDNA-specific dye Bind sequence independently to the minor groove of dsDNA. • Binding affinity is more than 100 times higher than that of ethidium bromide. • fluorescence of the bound dye is more than 1000fold higher than that of the free dye Taqman Assay • FRET mode • Principle: An oligonucleotide probe is labeled at one end with a fluorophore and in the middle or at the other end with a fluorescence quencher. When the probe binds to the target site in a PCR product, the 5’– 3’exonuclease activity of Taq DNA polymerase cleaves it freeing the fluorophore from quencher, thereby producing an increase in fluorescence. Factors on Taqman Assay • Distance between quencher and fluorophore 1. Optimal distance: 6 to 14 bases. (Ju et al., 1995, 1996) 2. Location of the quencher from the traditional 3’ position to an internal one increases the sensitivity of probe. • Taq DNA polymerase Sheering without cleavage is detrimental for the assay. Molecular Beacon • Contact mode • Principle: Molecular beacons are single-stranded nucleic acid molecules with a stem-and-loop structure. The loop portion of the molecular beacon hairpin is complementary to a target sequence. The stem is formed by two sequences that are complementary to each other. In the hairpin formation, the fluorophore, attached to one end of the probe, is quenched by the quencher, attached to the other end of the probe, and no fluorescence is emitted. On hybridization of the molecular beacon to its target the stem dissociates, causing the quencher and the fluorophore to move away from each other, resulting in the restoration of fluorescence. Fig 3. Structure and principle of operation of molecular beacons. Musa M. Mhlanga*,† and Lovisa Malmberg‡,1.(2001) Fig 4. Phase transitions of molecular beacons.When annealed, the molecular beacon–target hybrid is fluorescent. As the temperature is raised, the probe–target hybrid denatures and a nonfluorescent molecular beacon in a closed formation is formed. On further rise in temperature, the hairpin stem denatures and the molecular beacon forms a fluorescent random coil. Fig 5. “window of discrimination.”: higher fluorescence perfectly complementary hybrids can be distinguished from mismatched hybrids Bottom curve: in the absence of target. Top curve:in the presence of perfectly complementary target. Middle curve:in the presence of a target containing a mismatched nucleotide at the same position. Limiting Factors in Molecular Beacons • Compete with the opposite strand of the amplicon for binding to its complementary target • Quenching of the fluorophore in the open formation In the same oligonucleotide the quencher remains close enough to partly quench the fluorophore by a non-collisional mechanism Beacon Variants • Scorpion primer 1. A PCR primer with a hairpin structure at the 5’-extension 2. The linker stops DNA polymerase from replicating the stem-loop. 3. When primer extends and the target is synthesized, the stem-loop unfolds and hybridizes with target 4. Unimolecular mechanism ensures faster kinetics and greater stability of the probe-target complex • Catalytic molecular beacons combination of the molecular beacon with DNAzymes • PNA Beacons Light-up Probe • A peptide nucleic acid (PNA) to which an asymmetric cyanine dye is tethered (Fig 6.) 1. Deoxyribose-phosphate backbone of DNA has been replaced by a structurally homomorphous backbone of N- (2-aminoethyl) glycine units in PNA. 2. PNA is charge-neutral 3. It hybridizes faster, and forms more stable sequence than the natural nucleic acids 4. PNA/DNA complex is either double or triple-stranded • No quencher • Thiazole orange(TO) as fluorophore 1. Strongly fluorescent upon hybridization 2. Fold back onto the PNA interacting with its bases, causing free-probe fluorescence • Sensitive to mismatches A single-base mismatch is sufficient to prevent probe hybridization and subsequent fluorescence enhancement. • It does not interfere with the PCR process. Bind at annealing temperature and dissociate during elongation Fig 6. a) Chemical structure of light-up probes. b) Light-up probes interact with single-stranded target nucleic acid. Nicke Svanvik,* Gunnar Westman,† Dongyuan Wang,* and Mikael Kubista*,1.(1999) Factors in Light-up Probe • Fluorescence of the free probe. The free probe fluorescence may vary significantly, since the dye interacts differently with four nucleobases. The fluorescence enhancement upon hybridization of is mainly determined by the free probe fluorescence. Merits of Fluorescent Techniques in PCR • Fast and easy to perform • Reduce the risk of contamination • Results have a high precision • Real-time • Quantitative analysis Further Work • Optimal design of the probe • The interaction between the dye and template • Impact of environment on fluorescence Reference 1. Wittwer, C. T., Herrmann, M. G., Moss, A. A., and Rasmussen,R. P. (1997) Continuous fluorescence monitoring of rapid cycle DNA amplification. Biotechniques 22, 130–131, 134–138. 2. Haugland, R. P. (1996) Handbook of Fluorescent Probes and Research Chemicals (Spence, M. T. Z., Ed.), 6th ed., Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR. 3. J. Isacsson,1,2 H. Cao,3 L. Ohlsson,3 S. Nordgren,1,2 N. Svanvik,1 G. Westman,4 M. Kubista,1 R. Sjo¨back2. and U. Sehlstedt3 (2000) Rapid and specific detection of PCR products using light-up probes. Molecular and Cellular Probes (2000) 14, 321–328 4. H. Ozaki, L.W. McLaughim, The estimation of distances between specific backbonelabeled sites in DNA using fluorescence resonance energy transfer, Nucleic Acids Res. 20 (1992) 5205. 5. Tyagi,S., Bratu,D.P. and Kramer,F.R. (1998) Multicolor molecular beacons for allele discrimination. Nat. Biotechnol., 16, 49±53. 6. Lakowicz,J.R. (1999) Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, NY. 7. Bernacchi,S. and Mely,Y. (2001) Exciton interaction in molecular beacons: a sensitive sensor for short range modiÆcations of the nucleic acid structure. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, e62. 8. K.J. Livak, S.J.A. Flood, J. Marmaro, W. Giusti, PCR Methods Appl. 4 (1995) 357–362. 9. Ju J, Ruan C, Fuller CW, Glazer AN, Mathies RA. Fluorescence energy transfer dye-labeled primers for DNA sequencing and analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995;92:4347_/51. 10. Ju J, Glazer AN, Mathies RA. Cassette labeling for facile construction of energy transfer fluorescent primers. Nucleic Acids Res 1996;24:1144_/8. 11. Dmitri Proudnikov *, Vadim Yuferov, Yan Zhou, K.Steven LaForge, Ann Ho, MaryJeanne Kreek (2002) Optimizing primer_/probe design for fluorescent PCR. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 123 (2003) 31_/45 12. Crockett AO, Wittwer CT. Fluorescein-labeled oligonucleotides for real-time PCR: using the inherent quenching of deoxyguanosine nucleotides. Anal Biochem 2001;290:89_/97. 13. Kurata S, Kanagawa T, Yamada K, Torimura M, Yokomaku T, Kamagata Y, Kurane R. Fluorescent quenching-based quantitative detection of specific DNA/RNA using a BODIPY†-FL-labeled probe or primer. Nucleic Acids Res 2001;29:e34. 14. Irina Nazarenko, Rick Pires, Brian Lowe, Mohamad Obaidy and Ayoub Rashtchian. (2002) Effect of primary and secondary structure of oligodeoxyribonucleotides on the fluorescent properties of conjugated dyes. Nucleic Acid Research, 2002, Vol.30,No.9 2089-2195. 15. Musa M. Mhlanga*,† and Lovisa Malmberg‡,1.(2001) Using Molecular Beacons to Detect Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms with Real-Time PCR.. METHODS 25, 463–471 (2001) 16. Tyagi,S., Bratu,D.P. and Kramer,F.R. (1998) Multicolor molecular beacons for allele discrimination. Nat. Biotechnol., 16, 49±53. 17. Tyagi, S., Bratu, D. P., and Kramer, F. R. (1998) Nat. Biotechnol. 16, 49–53. 18. De-Ming Kong a, Yan-Ping Huanga, Xiao-Bin Zhang a, Wei-Hong Yang c, Han-Xi Shen a,., Huai-Feng Mia,b (2003) Duplex probes: a new approach for the detection of specific nucleic acids in homogenous assays. Analytica Chimica Acta 491 (2003) 135–143 19. S.K. Poddar, Mol. Cell. Probe 14 (2000) 25–32. 20. A. Solinas, L.J. Brown, C. McKeen, J.M. Mellor, J.T.G. Nicol, N. Thelwell, T. Brown, Nucleic Acids Res. 29 (2001) e26. 21. Nicke Svanvik,* Anders Ståhlberg,* Ulrica Sehlstedt,† Robert Sjo¨back,‡ and Mikael Kubista*,1 (2000) Detection of PCR Products in Real Time Using Light-up Probes. Analytical Biochemistry 287, 179–182 (2000) 22. J. Isacsson,1,2 H. Cao,3 L. Ohlsson,3 S. Nordgren,1,2 N. Svanvik,1 G. Westman, M. Kubista,1 R. Sjo¨back2. and U. Sehlstedt3 (2000) Rapid and specific detection of PCR products using light-up probes. Molecular and Cellular Probes (2000) 14, 321–328 23. Egholm, M., Buchardt, O., Christensen, L., Behrens, C., Freier, S. M., Driver, D. A. et al. (1993). PNA hybridizes to complementary oligonucleotides obeying the Watson-Crick hydrogen-bonding rules. Nature 365, 566–8. 24. Nicke Svanvik,* Gunnar Westman,† Dongyuan Wang,* and Mikael Kubista*,1.(1999) Light-Up Probes: Thiazole Orange-Conjugated Peptide Nucleic Acid for Detection of Target Nucleic Acid in Homogeneous Solution. Analytical Biochemistry 281, 26–35 (2000) 25. Natalia E. Broude.(2002) Stem-loop oligonucleotides:a robust tool for molecular biology and biotechnology. Biotechnology Vol.20 No.6 June 2002 26. Salvatore A. E. Marras*, Fred Russell Kramer and Sanjay Tyagi. (2002) Effciencies of fluorescence resonance energy transfer and contact-mediated quenching in oligonucleotide probes. Nucleic Acids Research, 2002, Vol. 30 No. 21 e122