Emory-Morrow-Karthikeyan-Neg-GSU-Round5

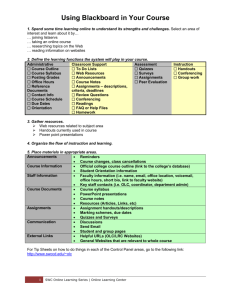

advertisement