Q&A: 'Lucy' Discoverer Donald C. Johanson

advertisement

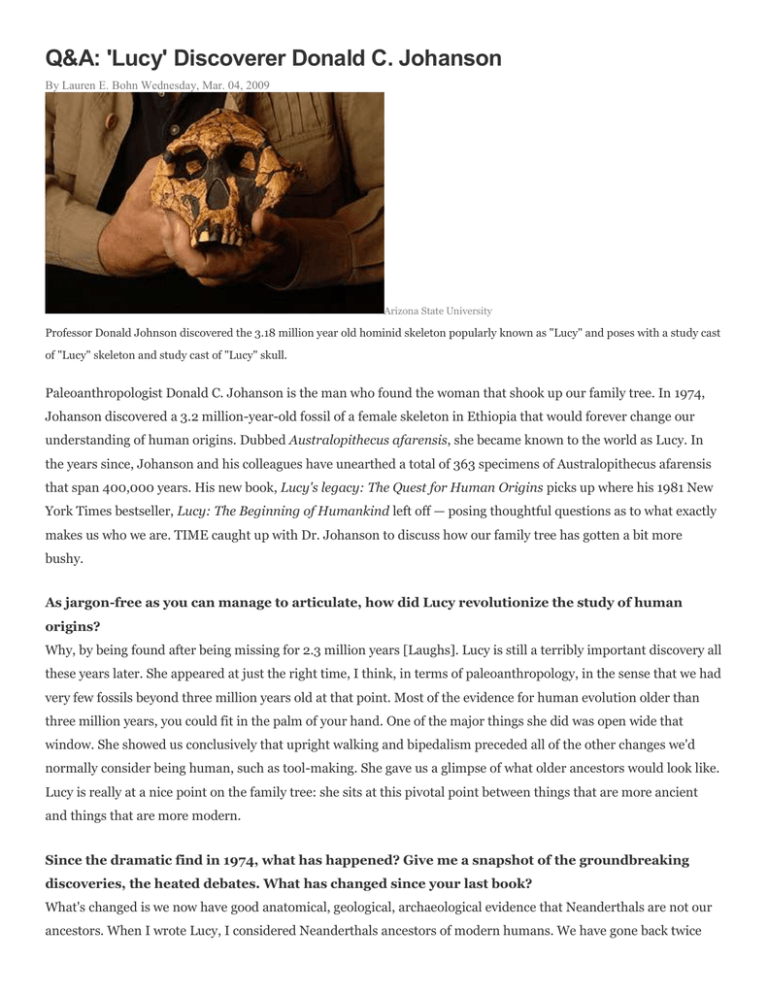

Q&A: 'Lucy' Discoverer Donald C. Johanson By Lauren E. Bohn Wednesday, Mar. 04, 2009 Arizona State University Professor Donald Johnson discovered the 3.18 million year old hominid skeleton popularly known as "Lucy" and poses with a study cast of "Lucy" skeleton and study cast of "Lucy" skull. Paleoanthropologist Donald C. Johanson is the man who found the woman that shook up our family tree. In 1974, Johanson discovered a 3.2 million-year-old fossil of a female skeleton in Ethiopia that would forever change our understanding of human origins. Dubbed Australopithecus afarensis, she became known to the world as Lucy. In the years since, Johanson and his colleagues have unearthed a total of 363 specimens of Australopithecus afarensis that span 400,000 years. His new book, Lucy's legacy: The Quest for Human Origins picks up where his 1981 New York Times bestseller, Lucy: The Beginning of Humankind left off — posing thoughtful questions as to what exactly makes us who we are. TIME caught up with Dr. Johanson to discuss how our family tree has gotten a bit more bushy. As jargon-free as you can manage to articulate, how did Lucy revolutionize the study of human origins? Why, by being found after being missing for 2.3 million years [Laughs]. Lucy is still a terribly important discovery all these years later. She appeared at just the right time, I think, in terms of paleoanthropology, in the sense that we had very few fossils beyond three million years old at that point. Most of the evidence for human evolution older than three million years, you could fit in the palm of your hand. One of the major things she did was open wide that window. She showed us conclusively that upright walking and bipedalism preceded all of the other changes we'd normally consider being human, such as tool-making. She gave us a glimpse of what older ancestors would look like. Lucy is really at a nice point on the family tree: she sits at this pivotal point between things that are more ancient and things that are more modern. Since the dramatic find in 1974, what has happened? Give me a snapshot of the groundbreaking discoveries, the heated debates. What has changed since your last book? What's changed is we now have good anatomical, geological, archaeological evidence that Neanderthals are not our ancestors. When I wrote Lucy, I considered Neanderthals ancestors of modern humans. We have gone back twice the age of Lucy, six million years. And we see that upright bipedal walking goes back that far in time. We have been surprised by the discovery of these little hobbits in Indonesia, something that nobody would have ever predicted. There's been the wonderful discovery of the Dikika baby which is telling us interesting things about the ontogeny, the growth and development, of our ancestors. The tree has gotten a little bushier. The story is becoming fuller and more interesting with lots of new characters. To set the record straight, it was the Beatles' song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" that gave birth to the hominid's name, correct? Yes, the whole camp was listening to Beatles' tape because I was a great Beatles fan, and "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" was playing and this girl said, well if you think the fossil was a female, why don't you name her Lucy? Initially I was opposed to giving her a cute little name, but that name stuck. Why do you think she so successfully captured the public imagination? It's not particularly common for a fossil to become a household name. I think she's captured the public's attention for a number of reasons. One, she's fairly complete. If you remove the hand bones and foot bones, she's 40% complete, so one actually gets an image of an individual, of a person. It's not just like looking at a jaw with some teeth. People can envision a little three-and-a-half foot tall female walking around. Also, I must say, her name is one that people find easy and non-threatening. People think of her as real personality. Lucy's an international celebrity; she's toured museums as a good-will ambassador. As a spokeswoman for human evolution, what does she say? Well I think the major message she brings to all the people who have an opportunity to see her or understand who she was is that the evidence for human evolution is irrefutable. She broadcasts that loud and clear. And not only Lucy, but many of the other fossils that have been found since, that we are all united by our past, that we all have a common history and though we may be vastly different, our origins all lead back to the crucible of human evolution that is Africa. She's announcing: "You are all my descendants and regardless of who we are, we are all, in fact today, Africans." How do you look at her? It's almost as though throughout the book, you view her, though she's an ancestor, as your child? Oh, exactly. She's an acquaintance, a good friend. I think one does develop an affinity to discoveries that one makes. She's so incredibly important in terms of our lives. How do I think of her? It's a very interesting question because if I had the ability to travel back in time, with only one choice of a place to go, my answer is quite simple. I'd want to be standing on the hill overlooking where Lucy and her cohorts were living when she fell into that lake and died. I'd like to see what she looked like, though I don't think I'd want to get pretty close to her. Here's a zinger: what makes us human? What makes us human depends on what place on our evolutionary path we're talking about. If you go back six million years ago, what makes us human is that we were walking up right. That's all. If you go to 2.6 million years ago, it's the fact that we're designing and making stone tools. And at 2 million years ago what makes human is our large brains that are at least two and half times the size of a chimp's. At twenty thousand years ago, what makes us human is the ability to make beautiful cave art. It's all relational. And if you look at us today, I wonder if we are human. Where are we going as a species? You'll have to call me after a few martinis [Laughs]. Where we are going as a species is a big question. Human evolution certainly hasn't stopped. Every time individuals produce a new zygote, there's a reshuffling and recombination of genes. And we don't know where all of that is going to take us. 1. Why was Lucy such an important discovery? 2. How do we know she was bipedal? Why would she still use trees? 3. What makes us human, in terms of looking at the fossil record? (What features are unique to the human line)?