Global economic prospects have continued to deteriorate with the

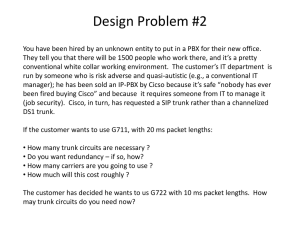

advertisement