study-guide-French-New-Wave

advertisement

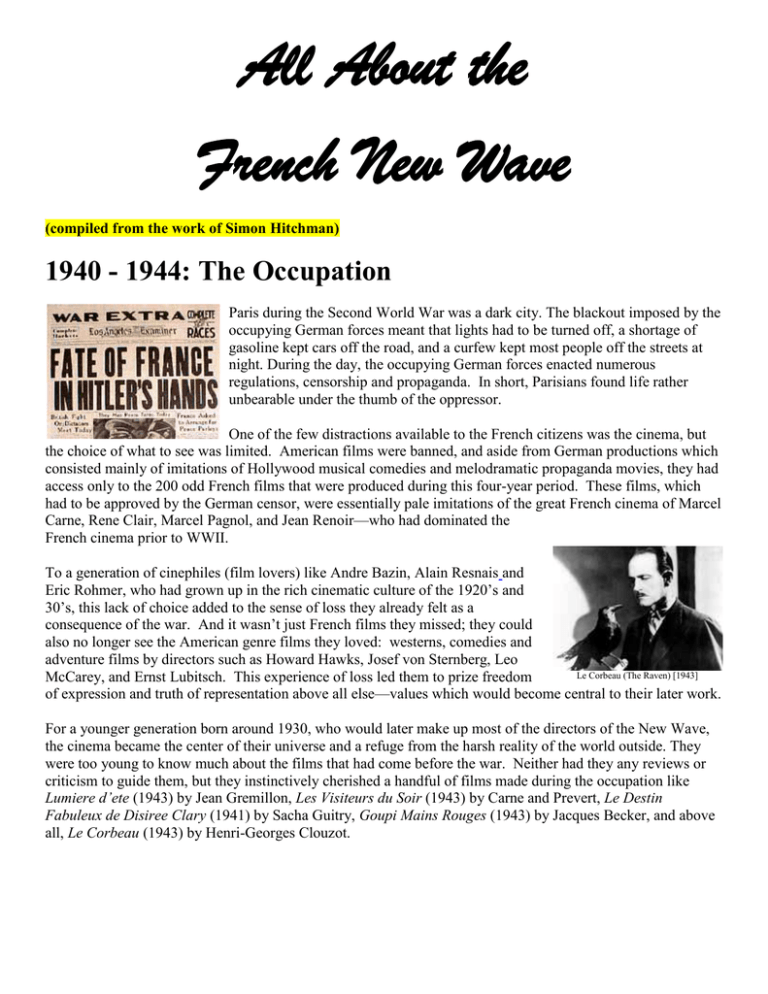

All About the French New Wave (compiled from the work of Simon Hitchman) 1940 - 1944: The Occupation Paris during the Second World War was a dark city. The blackout imposed by the occupying German forces meant that lights had to be turned off, a shortage of gasoline kept cars off the road, and a curfew kept most people off the streets at night. During the day, the occupying German forces enacted numerous regulations, censorship and propaganda. In short, Parisians found life rather unbearable under the thumb of the oppressor. One of the few distractions available to the French citizens was the cinema, but the choice of what to see was limited. American films were banned, and aside from German productions which consisted mainly of imitations of Hollywood musical comedies and melodramatic propaganda movies, they had access only to the 200 odd French films that were produced during this four-year period. These films, which had to be approved by the German censor, were essentially pale imitations of the great French cinema of Marcel Carne, Rene Clair, Marcel Pagnol, and Jean Renoir—who had dominated the French cinema prior to WWII. To a generation of cinephiles (film lovers) like Andre Bazin, Alain Resnais and Eric Rohmer, who had grown up in the rich cinematic culture of the 1920’s and 30’s, this lack of choice added to the sense of loss they already felt as a consequence of the war. And it wasn’t just French films they missed; they could also no longer see the American genre films they loved: westerns, comedies and adventure films by directors such as Howard Hawks, Josef von Sternberg, Leo Le Corbeau (The Raven) [1943] McCarey, and Ernst Lubitsch. This experience of loss led them to prize freedom of expression and truth of representation above all else—values which would become central to their later work. For a younger generation born around 1930, who would later make up most of the directors of the New Wave, the cinema became the center of their universe and a refuge from the harsh reality of the world outside. They were too young to know much about the films that had come before the war. Neither had they any reviews or criticism to guide them, but they instinctively cherished a handful of films made during the occupation like Lumiere d’ete (1943) by Jean Gremillon, Les Visiteurs du Soir (1943) by Carne and Prevert, Le Destin Fabuleux de Disiree Clary (1941) by Sacha Guitry, Goupi Mains Rouges (1943) by Jacques Becker, and above all, Le Corbeau (1943) by Henri-Georges Clouzot. France After The War In 1944 France was liberated from German occupation by the Allied forces. In the years that followed the Liberation, cinema became more popular than ever before. French films such as Marcel Carne’s Les Enfants du paradise (1945) and Rene Clement’s La Bataille du Rail (1946) were a great success. Italian and British imports were also popular. But most popular of all were the stockpile of films now streaming in from Hollywood. During the occupation the Nazis had banned the import of American films. As a result, after the war, when the ban was lifted by the 1946 Blum-Byrnes Agreement, nearly a decade’s worth of missing films arrived in French cinemas in the space of a single year. It was a time of exciting discoveries for film enthusiasts eager to catch up with what had been happening in the rest of the world. Reviews and Journals The Liberation brought with it a great desire for self-expression, open communication and understanding. The discussion of film, inevitably, became part of the discourse. Journals, such as L’Ecran Francais, became a platform for writers like Andre Bazin to develop their theories and convey their enthusiasm for film. Bazin saw cinema as an art form, and one that deserved serious analysis. His interest was in the language of film – favoring the discussion of form over content. Such an attitude tended to bring him into conflict with the predominantly left-wing writers at the paper, who were more concerned with the political standpoint of a film. Andre Bazin Another writer at the magazine who shared Bazin’s sense of aesthetics was Alexandre Astruc. In 1948 he wrote an article titled “Birth of a New Avant-Garde: The Camera as Pen,” in which he argued for cinema (a counterpart to literature) to become a more personal form, in which the camera literally became a pen in the hands of a director. The article would become something of a manifesto for the New Wave generation and a first step in the development of “auteur theory.” Another magazine that was quite popular with this new generation of cinephiles was Le Revue du Cinema. This was a publication devoted to the arts and, therefore, much less concerned with politics and issues of social commitment. American cinema was discussed as much as European cinema, and there were in-depth studies of directors like D.W. Griffith, John Ford, Fritz Lang, and Orson Welles. Andre Bazin contributed some important articles to the magazine on cinema technique, as did the young Eric Rohmer, whose piece, “Cinema, the Art of Space” would have a lasting influence on the directors of the New Wave. Film Clubs The same enthusiasts who avidly read the film journals now began setting up film clubs, not just in Paris, but all over France. The most famous of these was Henri Langlois’ Cinematheque Française, which first opened its doors in 1948. The cinema, which he co-founded with Georges Franju, was small; in fact, it accommodated only 50 seats, but the program of films shown was both comprehensive and eclectic, and it soon became a quite popular among serious film enthusiasts. Langlois believed the Cinematheque was a place for learning, not just watching, and he truly wanted his audience to understand what they were seeing. It became his practice to screen in a single evening several films that were different in style, genre, and country of origin. Sometimes he would show foreign films without translation or silent films without musical accompaniment. This approach, he hoped, would focus the audience’s Henri Langlois attention on the techniques behind what they were watching. He hoped to bring to light the links connecting films that might otherwise appear very different. It was here, at the Cinematheque, that many of the important figures of the New Wave first met. Francois Truffaut, only sixteen, was already an accomplished film student. From a young age, the cinemas of Paris had been his refuge from an unhappy home life. He had even set up his own cine-club, Le Cercle Cinemane, although it only lasted for one session. Jean-Luc Godard was another who immersed himself in the cine-clubs. He was studying ethnology at the Sorbonne when he first started going to the Cinematheque. For him too, cinema became something of a refuge. He later wrote that the cinema screen was “the wall we had to scale to escape from our lives.” Alain Resnais, Jacques Rivette, Claude Chabrol, Roger Vadim, Pierre Kast, and several others who would later become directors, received much of their film education at film clubs like the Cinematheque and The Cine-Club du Quartier Latin. For true film lovers like these, watching films was only part of the experience. They would also collect stills and posters, read and discuss the latest film articles, and make lists of favorite directors. It was all a way of putting what they were watching into some kind of perspective and developing their own critical viewpoints. Another avid member of the cine-club audience was Eric Rohmer. He had already published articles in other film journals, and now, with his two friends Rivette and Godard, he set up his own review called La Gazette Du Cinema. Although the paper had only a small circulation, it was a means whereby they could express their views on some of the films they were watching. Others like Truffaut and Resnais soon followed, writing articles for magazines like Arts and Les Amis du Cinema. Cahiers du Cinema The most important and popular film journal of all first appeared in 1951. Set up by Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Andre Bazin out of the ashes of the La Revue du Cinema, which had closed down the previous year, it was called Les Cahiers du Cinema. The first issues of the review, with its distinctive yellow cover, featured the best critics of the time writing scholarly articles about film. However, it was with the arrival of a younger generation of critics, including Rohmer, Godard, Rivette, Chabrol, and Truffaut that the paper really began to “make waves,” so to speak. Bazin had become something of a father figure to these young critics. He was especially close to Truffaut, helping to secure his release from the young-offenders institute, where he was sent as a teenager, and later from the army prison where he was locked up for desertion. At first, Bazin and Doniol-Valcroze allowed these young folks a small amount of column space to air their often combative opinions, but in time their articles gained more and more attention and their status rose accordingly. One conviction that these young writers shared was a disdain for the mainstream "tradition de qualite,” which dominated French cinema at the time. In 1953 Truffaut wrote an essay for Cahiers entitled "A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema,” in which he vehemently denounced this tradition of adapting safe literary works and filming them in an old fashioned and unimaginative way. He argued that this style of cinema wasn’t visual enough and relied too much on the screenwriter. He and the others labelled it “cinema de papa,” and compared it unfavorably with the work of filmmakers from elsewhere in the world. Bazin delayed the article’s release for a year, fearing that they would lose readers and anger the filmmakers who were being attacked. When it was eventually published, it did cause offence, but there was also considerable agreement. The passionate and irreverent style of Truffaut’s writing, like that of the other young critics, was a shift away from the hitherto austere tone of Cahiers. It brought the journal both a notoriety and popularity it hadn’t had before. Now he, Rohmer, Godaard, Rivette, and Chabrol were given the opportunity to promote their favorite directors within the review and develop their theories. ... Favourite Directors Henri Langlois always believed that watching silent films was the best way to learn the art of cinema, and he frequently included films from this period in the Cinematheque Français program. As a result, the New Wave group had a great respect for directors like D.W. Griffith, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and Erich von Stroheim, who had pioneered the techniques of filmmaking in its early years. When they began making their own films, silent movies would continue to be a source of inspiration for the New Wave directors. Three German directors—Ernst Lubitsch, Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau—were held in Fritz Lang high esteem by the New Wave. Lubitsch’s sophisticated comedies were held up for their exemplary screenwriting and perfect dramatic construction. Lang, whose later American films were generally felt by most critics at the time to be inferior to his early masterpieces like Metropolis and M, was defended by the Cahiers critics who pointed out that the expressive mise-en-scene of his German films had been interiorized in the intense Film Noir dramas he was now making in Hollywood. They argued that these later films, such as Clash By Night and The Big Heat, were every bit as complex as his earlier works. Murnau, the director of masterpieces like Nosferatu and Sunrise, although largely forgotten by contemporary critics, epitomized for the New Wave an artist who used every technique at his disposal to express himself filmically. They sang his praises in the pages of Cahiers and helped to re-establish his reputation as a cinematic visionary. Another European influence on the New Wave was the Italian Neo-Realism movement. Directors like Roberto Rossellini (Rome, Open City) and Vittorio de Sica (The Bicycle Thieves) were going direct to the street for their inspiration, often using unprofessional actors in real locations. They cut the costs of filmmaking by using lighter, hand-held cameras, and post-synching sound. This approach enabled them to avoid studio interference and the demands of producers. Their tendency to “cut corners” resulted in more personal pictures. These lessons learned from the Neo-Realists would prove to be a major factor in the success of the Nouvelle Vague ten years later. Roberto Rossellini A number of American directors were also acclaimed in the pages of Cahiers du Cinema including not only well known directors like Orson Welles (Citizen Kane), Joseph L. Mankiewicz (The Barefoot Contessa) and Nicholas Ray (Rebel Without a Cause), but also lesser known B movie directors like Samuel Fuller (Shock Corridor) and Jacques Tourneur (Out of the Past). The Cahiers critics broke new ground when they wrote about these directors, as they had really never been taken so seriously before. They ignored the established hierarchy, focusing instead on the distinctive personal style and emotional truth they saw in these films. By contrast, contemporary French cinema was a major disappointment to the New-Wave group. The year that followed the Liberation of France saw the release of some outstanding films including Marcel Carne’s Les Enfants du Paradise, Robert Bresson’s Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, and Jacques Becker’s Falbalas. However, since then, complacency had set in. There was none of the frank honesty of Italian Neo-Realism. Instead, most of the films that dealt with the war and the Resistance seemed to be sentimentalized versions of what had really occurred. It was clear that the majority of people, including most French filmmakers, were not yet ready to confront the shame of the Vichy government and the many who had collaborated with the Nazis during the war. Rebel Without A Cause [1955] ... In their articles, the young critics showed their disdain for the tradition de qualite prevalent at the time. Even directors whom they had once admired, like Henri-Georges Clouzot and Marcel Carne, seemed now to have lost their ambition; content to play the studio game. Other directors with a more realistic style, such as Julien Duvivier, Henri Decoin and Jacques Sigurd, were equally disappointing; portraying a cynical view of contemporary society that was stylistically static and uninspired. For the New-Wave intelligensia, who had expected so much after the war, it felt like a betrayal; and it explains why their attacks in print were often so vitriolic. However, there were some contemporary directors who made personal films outside the studio system like Jean Cocteau (Orphee), Jacques Tati (Mon Oncle), Robert Bresson (Journal d’un cure de campagne), and JeanPierre Melville (Le Silence De La Mer), who were much admired. Melville was a real maverick who worked in his own small studio and played by his own rules. His example would influence all of the New Wave; in fact, he is frequently cited as a part of the movement himself. At the same time, the Cahiers critics praised certain French directors of an earlier era like Jean Vigo (L’Atalante), Sacha Guitry (Quadrille), and most of all Jean Renoir (La Regle du Jeu), who was held up as the greatest of French auteurs. Auteur Theory For the New-Wave critics, the “concept of the auteur” was the key theoretical idea underlying their aesthetic viewpoint. Although Andre Bazin and others had been arguing for some time that a film should reflect the director’s personal vision, it was Truffaut who first coined the phrase la politique des auteurs in his article "Une Certaine Tendance du Cinéma Français". He maintained that the best directors have a distinctive style, as well as consistent themes running through their films, and it is this individual creative vision that makes the director the true “author” of the film. At the time auteur theory was considered a radical new approach to cinema. Before, it had been the screenwriter, or the producer, or the Hollywood studio, who was seen as the principle creator of a picture. The Cahiers critics applied the theory to directors like Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks, who had previously been seen as merely excellent craftsmen, but had never been taken seriously as artists. By uncovering the complex depths in the work of directors like these, the young writers broke new ground, not only in the way a film was understood, but also in how cinema itself was perceived. Alfred Hitchcock ... Mainly as a result of this radical new way of looking at cinema, the reputation Howard Hawks of Cahiers du Cinéma began to grow. In Hollywood the review became essential reading, and directors like Fritz Lang, Joseph Mankiewicz and Nicholas Ray were photographed with a copy of the magazine in their hands. Filmmakers like these weren’t used to people discussing their work with such accuracy and depth. They were deeply impressed by these young enthusiasts with their strong opinions and perceptive insights into the art of cinema. Inevitably, as the ideas and writing of the Cahiers critics became better known, there was a backlash. The aggressiveness of the review was felt to be too extreme by some. It brought about a feeling of resentment, and even hatred, in those who were “targeted.” As a result a kind of warfare raged between the young radicals and the old guard of French cinema. Short Films The young group of writers at Cahiers du Cinéma were not content, however, with merely being critics. They wanted to be filmmakers too. At the time there were two recognized routes to becoming a director. One could go through a long apprenticeship as an assistant director until, after many years, he/she was finally deemed ready to call the shots. This approach was antithetical to the desires of impatient young directors with ideas of their own and a disdain for the conservative material they would have to work on. The other method was to apply for a short-film funding scheme. This government-approved scheme ensured that all films were made to a professional standard. In the end it enabled the candidate to obtain the work card needed to make features. Some of the older members of the New Wave began this way by making critically acclaimed documentaries: Georges Franju (Les Sang des bêtes, Hôtel des Invalides), Alain Resnais (Night and Fog, Toute Le Mémoire du Monde, Le Chant du Styrene), and Chris Marker (Les Satues Meurent Aussi, Dimanche a Pekin, Lettre de Siberie), and Pierre Kast (Les Femmes du Louvre). Others soon followed their example, including Louis Malle (Le Monde du Silence), Agnes Varda (La Pointe-Courte), and Jacques Demy (Le Sabotier du Val de Loire). The Cahiers group, however, rejected both of these approaches. They knew they would have to bypass the rules of the system if they wanted to break into the ... industry and make the kind of films they wanted to make. While still writing for the magazine, they gained experience and contacts. Chabrol worked as a publicist at 20th Century-Fox, Godard worked as a press agent, Truffaut worked as an assistant for Max Ophuls and Roberto Rossellini, and Rivette worked with Jean Renoir and Jacques Becker. Les Sang des Betes [1949] Sooner or later, though, they realized that if they wanted to direct, they would have to start by making short films, raising money any way they could. Rohmer began in 1950, directing Journal d’un Scélérat, followed by Charlotte et Son Steak. Rivette, working with a script by Chabrol, directed Coup du Berger. In 1952 Godard directed a documentary called Operation Beton about the building of the Grande Dixene dam in Switzerland. He made the film with funds he earned by actually working as a laborer on the dam. After selling this piece, he had the means to make two dramatic shorts: Une Femme Coquette and Tous Les Garcons S’Appellent Patrick. As they gained experience, their films became more sophisticated. Rohmer made Bérénice in 1954, La Sonate a Kreuzer in 1956, and Véronique et son Cancre in 1958, to increasingly high standards. Les Mistons [1957] ... Meanwhile, Truffaut had set up his own film company, Les Films du Carrosse, with the help of his wealthy new father-in-law, and in the summer of 1957, shot Les Mistons, based on a story by Maurice Pons. Pleased with the success of the film, its financial backer suggested he make another. Truffaut began making a short comedy set against the backdrop of the flooding that had been taking place in and around Paris at the time, but had trouble finding the right tone and handed over the footage he’d shot to Godard. Godard felt no obligation to follow Truffaut’s script, however, and created an unconnected story with an off-the-wall commentary that broke all the conventions followed by traditional filmmaking. This film, Une Histoire d’Eau, was the most original—and most New Wave—of all the short films produced at the time. Other important shorts made at this time, and in subsequent years, included Le Bel Indifferent (1957) by Jacques Demy, Pourvu Qu’On Ait L’Ivresse (1958) by Jean-Daniel Pollet, and Blue Jeans (1958) by Jacques Rozier. These were followed by first films from Maurice Pialet (Janine, 1961), Jean-Marie Straub (Machorka-Muff, 1963), and Jean Eustache (Du Cote de Robinson, 1964). New Developments When the New Wave directors graduated from making short films to feature films in the late 1950’s, their ability to do so came about largely as the result of a combination of fortunate coincidences. Up until this time, filmmaking had always been an expensive business, and it was necessary to have the backing of a major studio. Now new circumstances came into play that enabled them to bypass this stumbling block. After the war the Gaullist government had brought in subsidies to support Truffaut and crew on location homegrown culture. A further act, 1958’s "Constitution of the Fifth Republic,” resulted in more money being available for first time filmmakers than ever before. Private investment money became more readily available and distributors were keen to back new directors. At the same time, technological developments meant filmmaking equipment was becoming cheaper. New, lightweight, hand-held cameras, developed for use in documentaries, were now available, as were faster film stocks, which enabled filmmakers to use portable sound and lighting equipment. These advancements meant filmmakers no longer needed a studio to make a film. They could now go out and shoot on location using smaller crews set against authentic backdrops. Working fast on low budgets encouraged experimentation and improvisation and gave the directors more control over their work than they might have had otherwise. The First Wave Et Dieu... Crea La Femme (And God Created Woman) (1956) is often cited as the first New-Wave feature film. Directed by a 28 year old writer-director named Roger Vadim, and starring his then wife, 22 year old former model and dancer Brigitte Bardot, it celebrated beauty and youthful rebellion and proved that a low-budget film made by a firsttime director could be a success, both at home and abroad. Although it now appears somewhat dated, at the time this film was an inspiration to young directors hoping to make their first film on their own terms. An even more inspiring figure was Jean-Pierre Melville, whose 1956 crime caper Bob Le Flambeur (Bob the Gambler) was a landmark in the Et Dieu... Crea La Femme French thriller genre. Shot on location on the streets of Paris and in the (And God Created Woman) [1956] director’s own homemade studio, its portrayal of the doomed gambler of .... the title, was both grittily realistic and audaciously stylized. The NewWave critics quickly recognized that Melville was a force to be reckoned with: a maverick with an authentic cinematic vision all his own. Worlds away from Melville’s tough gangsters were the strange, haunting films of Georges Franju. Co-founder of the Cinématheque Francais, Franju had graduated from archivist to filmmaker with shorts like Le Sang des Bêtes shot in a Parisian slaughter house. His ability to combine the poetic and the graphic, and to evoke the uncanny in a realistic setting, were seen to full effect in La Tête Contre Les Murs (Head Against the Wall) (1958), and Les Yeux Sans Visage (Eyes Without a Face) (1959). Louis Malle made his name working with marine scientist Jacques Cousteau on the Palme d’Or-winning underwater documentary Le Monde Du Silence (The Silent World). Coming from a wealthy background, Malle was able to raise the money to make his feature film debut Ascenseur Pour L’Echafaud (Elevator to the Gallows) in 1957 when he was still only 25 years old. Featuring a breakthrough performance from Jeanne Moreau in the lead and Miles Davis groundbreaking soundtrack, the picture – a fatalistic film noir – was a success. He followed this up with Les Amants (The Lovers) in 1958, again starring Moreau. The film provoked considerable controversy over its frank treatment of sexuality, and partly as a result of this, became an even bigger success, establishing a reputation for the young director as a rising talent. Le Beau Serge [1958] Claude Chabrol was the first of the Cahiers critics to make the move into feature films. Using money inherited from his wife’s family, Chabrol wrote, directed, and produced Le Beau Serge (The Beautiful Serge) (1958), featuring Jean-Claude Brialy and Gerard Blain in the lead roles, despite having no previous filmmaking experience. Shot on location in a provincial village, using natural light, the film upset the professional establishment by breaking the rules of what they considered good filmmaking, and it was refused entry to Cannes. However, the director took it to the festival himself where it was well received, earning enough in sales to finance his next feature, Les Cousins (The Cousins) (1959). Set in Paris, Les Cousins again starred Brialy and Blain, in a plot that effectively reversed the scenario of Le Beau Serge. The film was both a critical (it won the Golden Bear at the 1959 Berlin Film Festival) and commercial success. Having broken through as a director, Chabrol used the production company he had set up to support the debut films of Jacques Rivette (Paris Nous Appartient) and Eric Rohmer (Le Signe du Lion). Cannes 59: The Wave Breaks The term New Wave first appeared in 1957 in an article in L’Express entitled “Report on Today’s Youth.” The article, by the journalist Francoise Giroud, and the book she published the following year called The New Wave: Portrait of Today’s Youth, had nothing to do with cinema, but was about the need for change in society. However, the term was borrowed by journalists who used it to apply to the young directors creating a storm at the 1959 Cannes Film Festival, and soon the phrase caught on internationally. The film most responsible for bringing the attention of the world to this new cinematic movement was Francois Truffaut’s Les Quatre Cents Coups (The Les Quatre Cents Coups (The 400 Blows) [1959] 400 Blows) (1959). It caused a sensation at the festival that year. Its young star, Jean-Pierre Leaud, was carried out of the screening in triumph and Truffaut won the best-director award. Suddenly the world’s media were talking about the New Wave. Ironically, Truffaut had been banned from the festival the previous year because of his uncomplimentary remarks about French cinema in Cahiers. Now he was a star director, and those who had opposed him were rapidly pushed aside. Also screened at Cannes that year was Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima, Mon Amour, which was awarded the International Critics’ Prize. Resnais had already made a name for himself as a documentary director with Nuit Et Brouillard (Night and Fog) (1955), the first film to focus on the Nazi concentration camps of the Second World War. Like the documentary, his debut feature film employed innovative use of flashback to illuminate themes of time and memory and the horror of war. The film was acclaimed for its originality and became an international hit. “All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun.” - JeanLuc Godard In Cannes,Truffaut met Georges de Beauregard, an enterprising producer willing to take a gamble on a young director. Truffaut introduced him to Jean-Luc Godard, who proposed several projects, including an idea Truffaut had come up with based on a story he had seen in a newspaper. Beauregard liked the scenerio and bought the rights from Truffaut for 100,000 francs. Godard was an unknown however, so as an added guarantee, Beauregard insisted that Godard’s friends, who were now well established, appear in the credits. Truffaut was credited with the screenplay and Chabrol as artistic advisor. More than any other film A Bout de Souffle (Breathless) (1960) exemplified .... the New Wave movement; serving as a kind of manifesto for the group. While the plot, reminiscent of a thousand Film Noir B movies, is simple, the film itself is stylistically complex and revolutionary in its breaking of traditional Hollywood storytelling conventions. All of the trademarks of the New Wave are evident: jump cuts, hand-held camerawork, a disjointed narrative, an improvised musical score, dialogue spoken directly to camera, frequent changes of pace and mood, and the use of real locations. As Godard said, the film was the result of “a decade’s worth of making movies in my head.” Jean-Luc Godard A Bout De Souffle (Breathless) [1960] .... À Bout de Souffle was a commercial and critical success, playing to packed houses in Paris, and winning the Silver Bear for Best Director at the Berlin Film Festival. Its stars, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg, became fashion icons for the young, and audiences across the world responded to the picture’s iconoclastic spirit. Godard had taken his first step toward reinventing cinema. Like Godard, Truffaut had a passion for American pulp crime novels and Film Noir. His own unconventional take on the genre began with his second picture which was adapted from a novel by David Goodis called Down There. This was a deliberate move away from what he felt the public expected of him after the autobiographical nature of his first film. Tirez Sur Le Pianiste (Shoot The Pianist) was packed with cinematic references and deliberate subversions of genre conventions. It was a chance for the director to enjoy himself and prove he wouldn’t be easily catagorized. Although considered a classic now, Tirez Sur Le Pianiste baffled audiences at the time who were used to a more conventional style of storytelling. The film was not a financial success, and Truffaut, who had planned to turn his company Les Films du Carrosse into a kind of New-Wave studio, was forced to lower his expectations. From this time forward he made it a rule only to produce his own films, and any projects sent to him, he referred to other producers. Zazie, Lola, Catherine and Les Bonnes Femmes The start of the 1960’s saw the release of a diverse collection of New-Wave films all featuring female characters at their centre. Typically unpredictable, Louis Malle followed Les Amants with Zazie Dans Le Metro (1960), a lively, surreal farce shot in colour. Adapted from a novel by Raymond Queneau, the story follows an eleven year old girl and her eccentric uncle on a mad cap chase around Paris. Claude Chabrol also reacted against his Les Bonnes Femmes [1960] previous work with .... Les Bonnes Femmes (1960), an unusual mix of Hitchockian thriller and documentary realism, examining the ups and downs in the lives of four shop girls. The film details their hopeful but ultimately doomed attempts at finding romance. Jacque Demy’s debut feature Lola (1961), set in the seaside town of Nantes, drew on musicals, fairytales, and the golden age of Hollywood for its inspiration; furthermore, it set the tone for all his subsequent pictures. Featuring Anouk Aimee in the title role, this Jules Et Jim [1961] .... often downbeat tale of lost love and the machinations of fate was told with a joie de vivre that would become characteristic of Demy’s unique cinematic oeuvre. That same year, Francois Truffaut was planning Jules et Jim the story of two friends who both fall in love with the free-spirited but capricious Catherine. He had initially come across the semi-autobiographical book by Henri-Pierre Roche by chance in a second hand bookshop, had fallen in love with it, and had considered making it his first feature. However, realizing how difficult it would be to get right, he put it to one side until he had more experience under his belt. Now he had the experience and used it to create what would become one of the most famous and popular films of the French New Wave. Jules et Jim (1961) was a stylistic tour de force, incorporating newsreel footage, photographic stills, freeze frames, voice over narration, and a variety of fluid moving shots executed to perfection by cameraman Raoul Coutard. Despite this, Truffaut stayed remarkably faithful to the source material. The unconventional love triangle at the centre of the story and the determination of Catherine (Jeanne Moreau) to find sexual satisfaction outside of society’s conventions caused much controversy at the time of the film’s release but did nothing to hinder the film’s success. The Left Bank Group The Left Bank Group, from left: Alain Resnais, Agnes Varda, and Jacques Demy (holding camera, front right) In the early 1960s, critic Richard Roud attempted to draw a distinction between the directors allied with the influential journal Cahiers du Cinéma and what he dubbed the “Left Bank” group. This latter group embraced a loose association of writers and filmmakers that consisted principally of the directors Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnes Varda. They had in common a background in documentary, a left-wing political orientation, and an interest in artistic experimen tation. .... Another associate of the group was the Nouveau-Roman novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet. In 1961 he collaborated with Alain Resnais on L’Annee Derniere A Marienbad (Last Year in Marienbad). The film’s dream-like visuals and experimental narrative structure, in which truth and fiction are difficult to distinguish, divided audiences, with some hailing it as a masterpiece, and others finding it incomprehensible. Despite the critical disagreements, the film won the Golden Lion at the 1961 Venice Film Festival, and its surreal imagery has become an iconic part of film history. L'Annee Derniere A Marienbad (Last Year At Marienbad) [1961] . Chris Marker began making documentaries in the early 50’s, collaborating with his friend Alain Resnais on Les Statues Meurent Aussi (1950-53), which begins as a simple film about African art and gradually changes into an anti-colonialist polemic. Over the following years he developed a unique essay style of documentary filmmaking. His one fictional film, La Jetee (1962), a science fiction story about a time traveller, composed almost completely of still photographs, has become a classic in its own right. Agnes Varda is the most celebrated female director to be associated with the New Wave. She began as a photographer, then turned to the cinema and directed La Pointe Courte (1954), a low-budget, documentary-like feature film about the dissolution of a marriage which, in its production method and style, presaged the coming New Wave. Over the following years, she made a number of shorts and documentaries, before directing Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962). This real-time portrait of a singer set adrift in the city as she awaits the results of a life or death medical report became one of the benchmarks of the Nouvelle-Vague movement. The Tide Turns Adieu Philippine [1962] .... In December 1962, Cahiers du Cinéma published a special issue on the “New Wave,” which included long interviews with Truffaut, Godard and Chabrol, and a list of 162 new French directors. Among the first time directors discussed were Jacques Doniol-Valcroze (L’eau a la Bouche (1960)), Pierre Kast (Le Bel Age (1960)), Luc Moullet (Un Steack Trop Cuit (1960)), Jean-Daniel Pollet (La Ligne de Mire (1960)), Jean-Pierre Mocky (Les Dragueurs (1960)), and Jacques Rozier (Adieu Philippine (1962)). The success of the early New Wave had opened the gates for a generation of unknown directors to break through into what had previously been a very closed industry. Films were now being made by young people, for young people, and starring young people. Inevitably, there was a media backlash. The failure at the box office of Tirez Sur Le Pianiste, Une Femmes est une Femmes and other high profile releases gave the press ammunition to attack the movement. They reproached the young directors of the New Wave for making films that were “intellectual and boring.” At the same time the old guard believed it was making a comeback with a string of successful films beginning with Rue des Prairies (1960), starring Jean Gabin. There was dissent too at Cahiers du Cinéma. Most of its leading writers were now directors and no longer had the time to devote to writing for the magazine. As a result, by the early 60’s, a second generation of young cinephiles had replaced the first group. This new group did not always share the same opinions as its predecessors, leading to clashes with editor-in-chief, Eric Rohmer. Supported by the new writers, Jacques Rivette took over as editor, and the sense of community at the review fractured. The production of the New Wave group film Paris Vu Par (1964) – a series of sketches by different directors – signalled the change. Rivette, and Truffaut who had supported him, were symbolically excluded from contributing. The split had begun. Each of the filmmakers associated with Cahiers now went their own, increasingly divergent, ways. "The Cinema is truth 24 times a second." - Jean-Luc Godard By the mid-60’s Jean-Luc Godard was probably the most discussed director in the world. The films came in rapid succession, each one a further step towards a personal reinvention of cinema. After A Bout de Souffle, came a political thriller, Le Petit Soldat (The Little Soldier) (1961), a technicolour wide screen musical, Une Femme Est Une Femme (A Woman is a Woman) (1961), a social drama about prostitution, Vivre Sa Vie (One Life to Live) (1962), and a war film, Les Carabiniers (The Soldiers) (1963). Anna Karina in Vivre Sa Vie (My Life to Live) [1962] These early films had made a star out of Belgian-French actress .... Anna Karina, whom Godard had married in 1961. With his next film, Le Mépris (Contempt) (1963), he reinvented Brigitte Bardot’s public image, giving her the chance to prove she could act. The film - a story about the breakup of a relationship set against the pressures of commercial filmmaking - became Godard’s biggest box office success, ensuring continued financial backing for his prolific output. In the following years, Godard continued to make films that established him as the definitive New Wave director. After the lush Mediterranean scenery of Le Mepris, he went back to the streets of Paris, showing a gritty view of the city in crime caper Bande A Part (Band of Outlaws) (1964), and an alternative view in the dystopian sci-fi feature Alphaville (1965). Next came a road trip to the South of France for the brilliant Pierrot Le Fou (1965). Pairing Jean-Paul Belmondo and Anna Karina and abounding with ideas and references to both high and low culture (it even features a cameo from B movie maestro Sam Fuller), the film was a culmination of all the director’s radical filmmaking techniques up to that point. Godard’s political views became increasingly central from now on. Masculin, Feminin (1966), was a study of contemporary French youth and their involvement with cultural politics. An intertitle refers to the characters as “the Weekend [1967] children of Marx and Coca-Cola.” Next came Made in the U.S.A (1966), a playful crime story inspired by Howard Hawks’s The Big Sleep (1945).2 ou 3 choses que je sais d'elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her) (1967), starred Marina Vlady as a woman leading a double life as housewife and prostitute. Le Chinoise (1967) focused on a group of students engaged with the ideas coming out of the student-activist groups in contemporary France. Later that year, Godard made a more colourful political film. Weekend (1967) follows a Parisian couple as they go on a trip across the French countryside to collect an inheritance. What ensues is a darkly comic, sometimes horrific, confrontation with the tragic flaws of the bourgeoisie. Weekend’s enigmatic closing title sequence concludes with the words “End of Cinema,” a declaration which signalled an end to the first period in Godard’s filmmaking career. Love, Murder, and Morality Tales Francois Truffaut followed Jules et Jim with La Peau Douce (Soft Skin) (1964) another story about an ill-fated love triangle, but this time in a contemporary setting. Despite excellent perfomances and a compelling narrative, the film was not a financial success, and, over the next few years, Truffaut’s career slowed as he worked on his book about Alfred Hitchcock, whilst struggling to get his film adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s Farenheit 451 off the ground. When he came to shoot it the larger-scale production was difficult for Truffaut. He was used to working on low budgets and unable to communicate easily with the English speaking crew; as a result, the final product failed to match its initial conception. Jacques Demy had his greatest success with his third film Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg) (1964). The film, staring a 20-year-old Catherine Deneuve, tells a tragic story of everyday life but is transformed by Demy .... into a tender romance in which all the characters sing their lines and the town is painted in a range of beautiful colours. The film was a critical and commercial success, winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes. He followed this with the equally captivating Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (The Young Girls of Rochefort) (1967). Catherine Deneuve in Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (The Umbrellas of Cherbourg) [1964] Louis Malle’s typically diverse range of 1960’s films included Vie Privee (A Very Private Affair) (1962) in which Brigitte Bardot played a virtual parody of her real life persona; Le Feu Follet (The Fire Within) (1963), the powerful study of a writer trying to find a reason not to kill himself; the internationally successful Viva Maria! (1965) which teamed Brigitte Bardot with Jeanne Moreau in a tale of revolution in South America; and Le Voleur (The Thief) (1967), a comedy drama about a thief starring Jean-Paul Belmondo. After the failure of the last of these, Malle admitted he was tired of the mainstream film industry, and, in 1969, he travelled to India, where he made two uncompromising documentaries about the poverty he found there. Le Feu Follet (The Fire Within) [1963] . .... In 1962 Eric Rohmer made La Boulangere de Monceau (The Bakery Girl of Monceau) (1962), the first in what would become a celebrated series of films released over the next ten years under the title Six Moral Tales. Each of the films, which included Ma Nuit Chez Maud (My Night with Maud) (1969) and Le Genou de Claire (Claire's Knee) (1970), explored the entanglements, temptations and disappointments facing contemporary relationships. In them Rohmer established a cinematic style all his own, notable for its economical camerawork, warmly ironic tone, and strict fidelity to the true representation of reality. More conventional in his approach than the other New-Wave directors,Claude Chabrol’s mid-1960’s output failed to draw the attention accorded to his contemporaries. Out of step with the mood of the times, for a while Chabrol appeared to lose direction. Then came the series of psychological thrillers starting with Les Biches (The Does) (1968), and including La Femme Infidele (The Unfaithful Wife) (1969), and Le Boucher (The Butcher) (1969), which established his world-wide reputation. Jacques Rivette’s debut feature Paris Nous Appartient (Paris Belongs to Us) (1960) had been a monumental undertaking, taking two years to make and featuring a cast of thirty actors. However its intricate plot and uneven pace found little favour with audiences. His next film, Le Religieuse (The Nuns) (1966) was considerably more commercial, becoming quite scandalous when the government blocked its release for a year. The relatively straightforward narrative of this film was, however, uncharacteristic of the director’s vision, and, it was with the highly experimental and original films that followed, including L’Amour Fou (Mad Love) (1968), Out 1 (1970), and Celine et Julie Vont en Bateau (Celine and Julie Go Boating) (1974), that Rivette made a more lasting impact. 1968 - Year of Revolution In the spring of 1968, a minor protest by students at Nanterre University quickly escalated, leading to major civil unrest all over France. On May 10th in Paris, there was a violent confrontation between student demonstrators and the police. Over the following days discontent with the Gaullist government spread into the labor force, and workers began joining in the protest with a series of strikes and factory occupations. Ultimately, the De Gaulle government held firm, and partly because of divisions within the leftist opposition, the protests died away. The Paris Riots, 1968 Earlier in 68, events in the world of cinema had helped to trigger the riots that followed. It began when Henri Langlois, who had set up and nurtured the Cinématheque Francaise, was fired as its head by the Minister of Culture Andre Malraux. Claiming administrative incompetence as his reason, Malreaux terminated the archive’s subsidy and moved to appoint a new head. The firing sparked protests among Parisian film students who continued to receive much of their education through screenings at the Cinematheque, as well as New-Wave directors like Truffaut, Godard, Rivette, and Resnais who proudly proclaimed themselves “children of the Cinématheque.” Even the Cannes Film Festival was drawn into the protest as Louis Malle and Roman Polanski resigned from the festival jury, and Truffaut and Godard burst into a screening and hung from the curtains to physically stop the festival from continuing. Support too came from abroad in the form of telegrams from world famous directors like Hitchcock, Kurosawa and Fellini. Eventually Malraux was forced to back down and Langlois was reinstated. Aftermath The Langlois affair showed that, despite their political and cinematic differences, the directors associated with the Nouvelle Vague could still come together as a group. Indeed, after their work came under attack from critics, and the film establishment began to reassert itself, they felt more willing to assert themselves as part of a movement than they had at the start. As Truffaut wrote in a 1967 issue of Cahiers du Cinéma: “Before, when we were interviewed – Jean Luc, Resnais, Malle, myself and others – we said, ‘The New Wave doesn’t exist, it doesn’t mean anything.’ But later, we had to change, and ever since that moment I’ve affirmed my participation in the movement. Now, in 1967, we are proud to have been and to remain part of the New Wave, just as one is proud to have been a Jew during the Occupation.” Then and Now: The New Wave Continues An enduring legacy of the French New-Wave movement was the inspiration it provided for similar movements in other countries. In America, the “movie brat” generation of filmmakers that emerged in the late 1960’s and 70’s, was profoundly influenced by the storytelling techniques pioneered by the Novelle-Vague directors. In Europe too, young directors in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Germany, and elsewhere, were motivated to break with the past and tell their own stories. Even further afield, in countries such as Japan, Brazil, and Canada, similar movements prospered for a while. In France the success of the Nouvelle Vague continued to open doors La Maman et la Putain for new directors. Barbet Schroeder (More (1969)) Jean Eustache (The Mother and the Whore) [1973] (La Maman et La Putain (1973)), Andre Techine (Paulina s’en Va .... (1975)), and Philippe Garrel (L’Enfant Secret (1979), made up part of what could be considered a post-New-Wave second wave. They, and other directors like Jean-Claude Biette, Claude Guiguet, and Paul Vecchiali, began, like their predecessors, writing for Cahiers du Cinéma, before turning to filmmaking themselves. In the 1980’s a new generation of young directors emerged in France. Dubbed by the media the "New New Wave," the three main figures in the group, Jean-Jacques Beineix, Luc Besson and Leos Carax, were quick to distance themselves from the earlier movement, expressing anti-New-Wave sentiments in interviews. Their films, which included the hits Diva (Beineix (1980), Subway (Besson (1985), Betty Blue (Beiniex (1986), The Big Blue (Besson (1988), and Les Amants du Pont-Neuf (Carax (1991), were criticized for favouring style over substance. Their style of filmmaking became known as the “cinema du look,” and, although popular, was felt by many to offer little more than slick visuals and alluring stars. La Belle Noiseuse [1991] . The tragic early death of Francois Truffaut in 1984 brought an end to the career of the best known and best loved of the French New-Wave directors. His later work, although varied and not always successful, included such highlights as the Oscar-winning Day for Night (1973), the poetic La Chambre Verte (The Green Room) (1978), and Le Dernier Metro (The Last Metro) (1980), a story of the Resistance which was a critical and boxoffice triumph in France. Apart from his work, Truffaut himself has become an icon and inspiration for impassioned, idealistic young directors, determined to remake cinema on their own terms. As for his Nouvelle-Vague contemporaries, they continue making waves in the twenty-first century. Godard, Chabrol, Rohmer, Rivette, Varda, Resnais, Marker, and others associated with the movement, are all now auteurs in their own right with an international following. Their prolific output continues to challenge audiences and expand the boundaries of cinematic expression. Retrospectives of their work and new prints of New Wave classics continue to keep alive a cultural revolution that produced some of the greatest films ever made and changed the course of cinema history.