Pediatric Head And Neck Disorders Introduction Neck masses are

advertisement

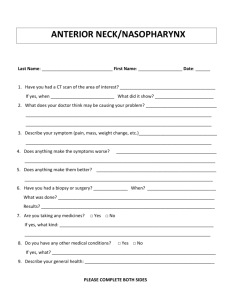

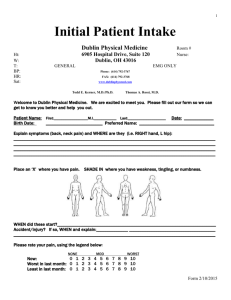

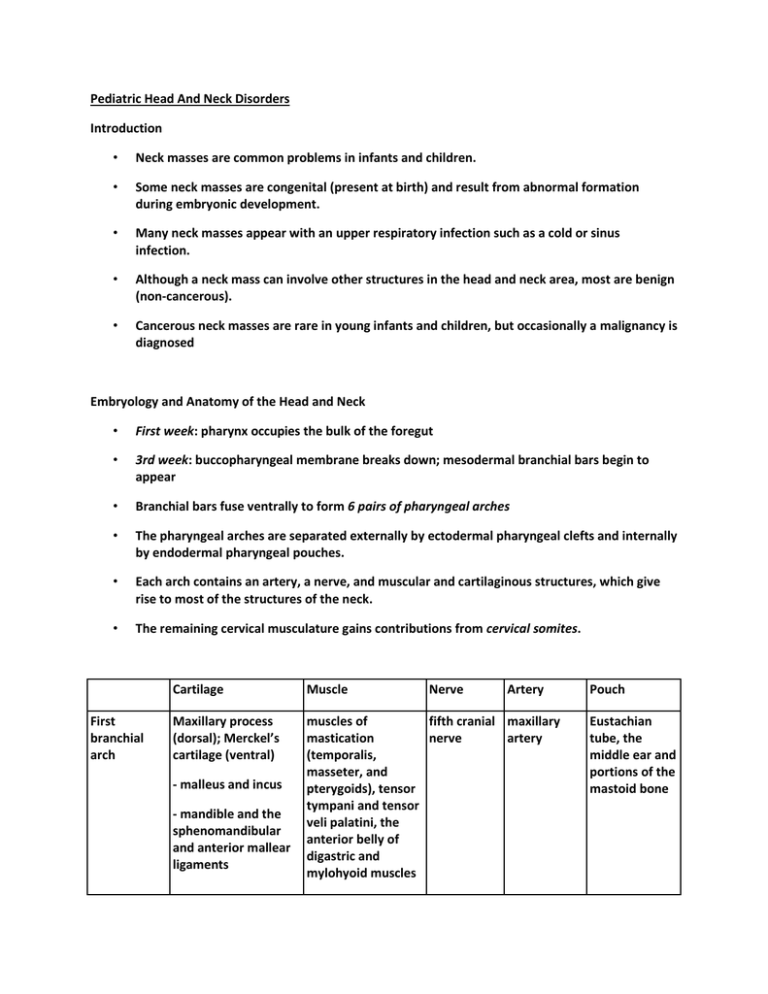

Pediatric Head And Neck Disorders Introduction • Neck masses are common problems in infants and children. • Some neck masses are congenital (present at birth) and result from abnormal formation during embryonic development. • Many neck masses appear with an upper respiratory infection such as a cold or sinus infection. • Although a neck mass can involve other structures in the head and neck area, most are benign (non-cancerous). • Cancerous neck masses are rare in young infants and children, but occasionally a malignancy is diagnosed Embryology and Anatomy of the Head and Neck • First week: pharynx occupies the bulk of the foregut • 3rd week: buccopharyngeal membrane breaks down; mesodermal branchial bars begin to appear • Branchial bars fuse ventrally to form 6 pairs of pharyngeal arches • The pharyngeal arches are separated externally by ectodermal pharyngeal clefts and internally by endodermal pharyngeal pouches. • Each arch contains an artery, a nerve, and muscular and cartilaginous structures, which give rise to most of the structures of the neck. • The remaining cervical musculature gains contributions from cervical somites. First branchial arch Cartilage Muscle Maxillary process (dorsal); Merckel’s cartilage (ventral) muscles of fifth cranial maxillary mastication nerve artery (temporalis, masseter, and pterygoids), tensor tympani and tensor veli palatini, the anterior belly of digastric and mylohyoid muscles - malleus and incus - mandible and the sphenomandibular and anterior mallear ligaments Nerve Artery Pouch Eustachian tube, the middle ear and portions of the mastoid bone Second branchial arch Reichert’s cartilage Third branchial arch Greater cornu and the Stylopharyngeus inferior body of the and superior and middle pharyngeal hyoid constrictors Common Ninth cranial carotid and nerve proximal portions of the internal and external carotid arteries Inferior parathyroids and thymus duct Fourth and sixth branchial arches Fuse to form the laryngeal cartilages 4th 4th 4th -subclavian (right) -superior parathyroids and possibly parafolliclar throid cells -Upper body and lesser cornu of the hyoid bone, styloid process, stylohyoid ligament, stapes superstructure Muscles of facial Seventh expression, cranial platysma, posterior nerve belly of the digastric, stylohyoid and stapedius 4th arch -cricothyroid and -superior inferior pharyngeal laryngeal constrictors nerve 6th arch 6th -remaining intrinsic Recurrent musculature of the laryngeal larynx nerve • • Stapedial artery -aortic arch (left) 6th -ductus arteriosus and pulmonaary artery The first and second arches grow in a cranial to caudal fashion, creating the epipericardial ridge. – Contains mesodermal rudiments of the sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, and the infrahyoid and lingual musculature – Nerves include the hypoglossal and spinal accessory The proliferation of mesoderm eventually causes overgrowth and narrowing of the third, fourth, and sixth arches into an ectodermal pit, known as the cervical sinus of His, that eventually becomes obliterated – If it fails to be obliterated or is partially obliterated, a branchial sinus, cleft, or cyst of types II, III, or IV may develop Thyroid gland • The thyroid gland originates during the fourth week of gestation as endoderm of the floor of the mouth in between the tuberculum impar and copula of the first and second pouches. • It descends as a bilobed diverticulum from the foramen cecum to pass in variable position to the hyoid bone to rest in the lower neck. Clinical Assessment • A physician will consider many factors when diagnosing a neck mass, including: – • • age, duration and number, family history, and any prior or ongoing illnesses, ear infections, and/or animal bites. Examination of neck masses may include the following: – careful visualization and palpation (feeling with the fingers) – identifying the specific location of the mass – checking for movement of the neck and the mass itself – observing redness, swelling, warmth, tenderness, drainage, or fluid Further tests may be needed to completely diagnose the type of neck mass and whether other tissues and structures in the neck are involved. Modalities of Treatment • Treating neck masses depends on the type of mass and whether there is infection. • As with all tumors, there are four main modalities of treatment. – Some tumors will naturally involute (e.g. hemangiomas), and nothing may need to be done. – Some tumors require excision, particularly benign tumors. – Some tumors require chemotherapy or radiotherapy, usually malignant tumors. – Of course there is overlap between all these groups, and some tumors require more than one form of treatment. Benign tumors of childhood Hemangiomas • Hemangiomas are the most common benign tumor in infants. • The average age when hemangioma appears is two weeks, deep hemangiomas may not be noticed until three to four months. • Approximately 60% of hemangiomas occur in the head and neck area. About 25% occur in the trunk and 15% occur in the arms or legs. • They demonstrate a rapid growth and then a period quiescence followed by a period of involution. • 50% of children will have complete resolution of the lesion by the age of 5, increasing to 70% resolution by the age of 7. • A CT with contrast or MRI with gadolinium will demonstrate the anatomy and vascularity of the lesion. • Since the majority of hemangiomas is small and regresses on their own without any treatment, it is usually not necessary for a child to be seen by a specialist in vascular anomalies. • A child should be referred to a vascular anomalies specialist if: • • the diagnosis is unclear • the hemangioma is large, growing rapidly, or at risk of causing endangering or disfiguring complications • the child has multiple hemangiomas in the skin, as this sometimes signifies a hemangioma in an internal organ and can be life-threatening Complications include • ulceration (skin breakdown), which can bleed or become infected; obstruction of vital functions; distortion of facial features; and, very rarely, internal bleeding or high output cardiac (heart) failure resulting from a hemangioma in an internal organ. • Only about 1% of hemangiomas cause life-threatening complications. • For hemangiomas that cause complications: • Systemic and intralesional steroid • Surgical excision Lymphangiomas • Lymphangiomas are lymphatic cysts that are isolated from their normal route of drainage into the venous system. • The embryological development of the lymphatic system is theorized by the centrifugal theory and the centripetal theory. – The centrifugal theory states that lymphatic channels grow outward from venous channels. – The centripetal theory states that lymphatic channels grown independently of venous channels. • Lymphangiomas are painless, usually in the posterior triangle of the neck that transilluminates. • It usually presents by age two; 90% present in first year. • Sudden increase in size is noted with upper respiratory infections, infection of the mass itself, or hemorrhage. • A CT is of greatest diagnostic value. – • Spontaneous regression is rare and surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Resection is contemplated only if it does not mutilate and is easily accessible or vital structures compromised. Recurrence rates are generally high because of the poor encapsulation and dissection planes. Branchial cleft cysts • Failure of branchial cleft involution leads to branchial cleft cysts, fistulas, or sinus tracts. • Usually occur superficially from the skin surface along the anterior border of the SCM to the deeper cervical recesses along the lateral wall of the pharynx. • They manifest with painless fluctuant swelling. Infection may initiate this swelling, causing a more acute, painful presentation • Branchial cleft cysts are most often classified based on the cleft or pouch of origin. • First branchial cleft cysts are rare, are located in the parotid gland or immediate periparotid region, and may have a direct connection with the external auditory canal. • Second branchial cleft cysts are common and have been divided into four types according to the Bailey classification system, which is based on anatomic relationships. • Type I: found anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle under the platysma and cervical fascia. • Type II: most common; they are located adjacent to and may adhere to the great vessels at the mandibular angle. • Type III: found between the internal and external carotid arteries adjacent to the pharynx. • Type IV: found against the pharyngeal wall. • Third and fourth branchial cleft cysts are extremely rare and are found adjacent to the laryngeal ventricle, posterior to the common carotid artery and jugular vein at the margin of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. • Fourth branchial cleft cysts are more common on the right side and are found along the course of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, especially anterior and inferior to the subclavian artery. Thyroglossal duct cysts • Most common midline mass encountered • As the biolbed thyroid diverticulum descends from the floor of the pharynx, a thyroglossal duct is created; failure of involution of any portion of this tract can lead to a thyroglossal duct cyst. • Arrest of normal descent of the gland can result in ectopic thyroid tissue. The pyramidal lobe, found in 40% of patients, is actually just the failure of closure of the inferior most portion of the thyroglossal duct. • The majority present in children and adolescents as an asymptomatic midline mass at or below the hyoid bone that commonly elevate with tongue protrusion. • An ultrasound is probably the best study to document the presence of normal thyroid tissue. A thyroid scan is of value in patients who are hypothyroid, are unable to tolerate an adequate thyroid ultrasound, or fail to demonstrate a normal thyroid by ultrasound. • The primary management of thyroglossal duct cysts is with Sistrunk procedure. Simple cyst excision results in a high rate of recurrence (50%). Pediatric Head and Neck Infections • Infection and inflammation of the cervical lymph nodes is the most common cause of pediatric neck masses. • Approximately 55% of pediatric patients have palpable lymph nodes that are not necessarily associated with an underlying systemic infection. • Cervical nodes that are asymptomatic and <1 cm in diameter may be considered normal in children under 12. The most common site of cervical adenitis is the submandibular or deep cervical nodes. • Lymphadenitis may be of viral, bacterial, fungal, parasitic, or not-infectious etiology. • The most common bacterial cause of cervical adenitis is Staphylococcus aureus and Group A Streptococci. • The cervical lymphadenopathy is usually tender and the patient may have associated symptoms of malaise and fever. • Typically the first line of defense is a round of antibiotics. When that doesn’t resolve the inflammation, a biopsy of the lymph node is done to remove it or to send it on for further testing. • Lateral neck infections may manifest as lymphadenitis, cellulitis, necrotic nodes or abscesses. • Radiographic imaging particularly CT or MR scanning may be helpful in distinguishing among these processes. • Node suppuration may occur, and needle aspiration or incision and drainage of the necrotic lymph node may be required. • The infections are usually polymicrobial, including aerobic organisms such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Niesseria, and anaerobes such as Fusobacterium, Peptostreptococcus, and Bacteroides. Peritonsillar abscess • Clinical manifestations of peritonsillar abscess include drooling and difficulty of swallowing, muffling of the voice (hot potato voice), referred pain to the ear and slight amount of trismus. • Management include antibiotics, needle aspiration, intraoral incision and drainage or external incision and drainage. • Examination may show the tonsil pushed midline, forward and downward; the uvula displaced away from the involved side. • The palate and tonsil are erythematous, tender and edematous. Retropharyngeal abscess • Retropharyngeal abscess is secondary to suppuration and break down of nodes in the retropharyngeal space • Examination reveals a bulge in the posterior pharyngeal wall • Symptoms include loss of appetite, difficulty of swallowing, and dyspnea if the swelling extends downward to obstruct the laryngeal opening • Imaging • Thickened retropharyngeal tissue • Straightening of the cervical lordosis • Air-fluid level • Anterior displacement of the airway • Lateral radiograph • Normal: 7mm at C-2, 14mm at C-6 for kids, 22mm at C-6 for adults • Technique dependent • • Extension • Inspiration Lateral radiograph sensitivity is 83%; compared to CT = 100% Ludwig’s angina • Ludwig’s Angina is a rapidly spreading submandibular & sublingual cellulitis w/o abscess resulting from an odontogenic or traumatic etiology. • Elevated floor of mouth, tongue protrusion, enlargement from massive submandibular and sublingual edema progresses rapidly within 8 to 20 hours. • Early airway control may be necessary and broad-spectrum antibiotics started. Scrofula (Tuberculous) • CXR is needed to rule out active pulmonary disease. • A PPD is usually strongly reactive. • Treatment usually is the same as for pulmonary TB with combinations of isoniazid, ethambutol, streptomycin, and rifampin. Scrofula (Nontuberculous) • In children, NTM is much more common than tuberculous mycobacteria. • Rarely exhibit fever or systemic symptoms. The CXR is usually normal, and PPD reactions are normal or only intermediate in reactivity. • Notoriously resistant to traditional anti-tuberculous agents alone and requires a combination of typical and atypical agents. Infectious mononucleosis • An exudative, almost necrotic tonsillitis and impressive cervical lymphadenopathy (sometimes hepatosplenomegaly). • Caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). • Labs: Heterophile antibodies (monospot) or titers of IgM and IgG • Treatment is usually supportive. In cases in which airway symptoms emerge, steroid and antibiotic therapy may be necessary. • Ampicillin and Amoxicillin have been associated with a rash in 90% of EBV patients. Kawasaki syndrome • Kawasaki syndrome is a multisystem vasculitis of unknown etiology occurring in young children under the age of 5. • Diagnosis is clinical and requires five of six criteria including: 1. fever greater than 5 days 2. conjuctival injection 3. reddening or injection of the oral cavity 4. reddening or desquamation of the palms and soles 5. polymorphous erythematous rash 6. cervical lymphadenopathy • The vasculitis is self-limited but may cause permanent cardiac damage as a result of coronary artery aneurysms in about 20% of patients that are untreated. • High dose aspirin is used in the acute phase, and intravenous immunoglobulin therapy reduces coronary aneurysm formation. Pediatric Head and Neck Cancer • Treatment of malignancies of the head and neck requires a significant commitment of expertise from multiple disciplines -- a team approach. • The team includes board certified specialists in otolaryngology, plastic and reconstructive surgery, radiation oncology, medical oncology, radiology, pathology, anesthesia and maxillofacial prosthodontics. • Speech pathologists, dieticians, case managers, and social workers provide vital support to the team. • All participate in treatment and reconstructive planning to assure a comprehensive level of specialty care and the greatest possibility of a positive outcome. • Surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy continue to be the primary treatment modalities for head and neck cancers. • A long-term commitment to the patient is required for initial treatment. • A prolonged follow-up period is required to rehabilitate speech and swallowing function and to detect recurrences or second primary tumors. • Head and neck malignancies exact a significant physical as well as psychological toll on patients and families. • Rehabilitation issues include airway management, speech, swallowing, trismus, and psychosocial issues.