List of suggested books for Inferencing

advertisement

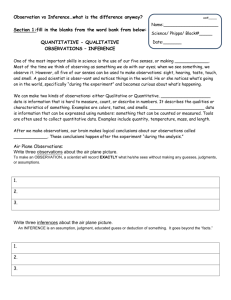

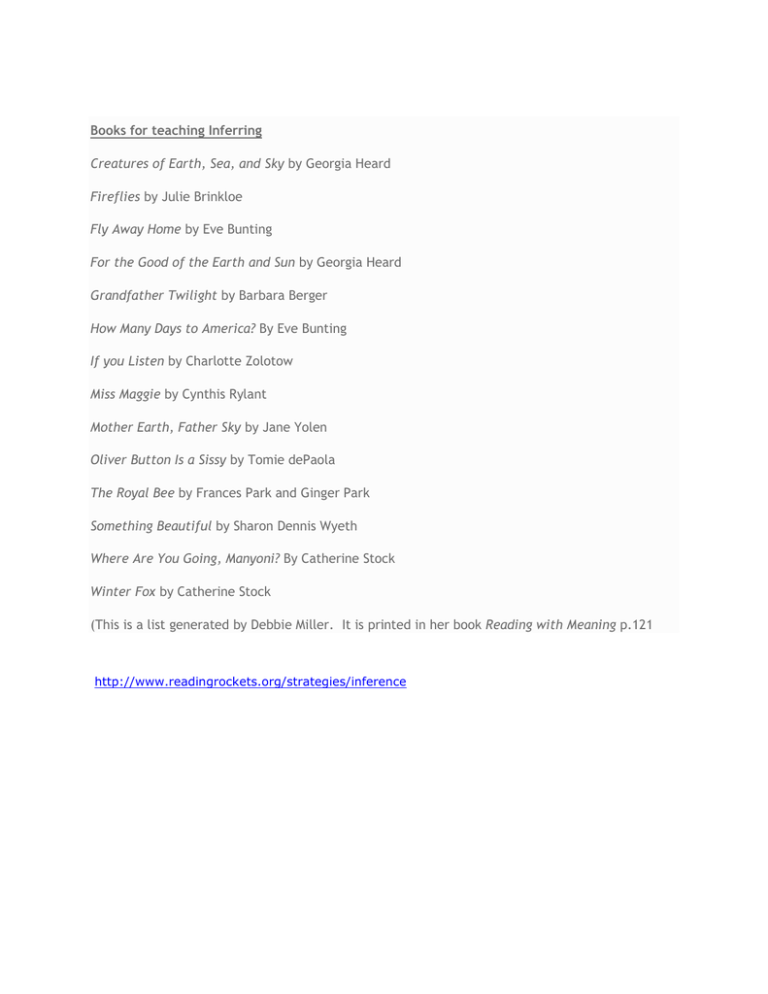

Books for teaching Inferring Creatures of Earth, Sea, and Sky by Georgia Heard Fireflies by Julie Brinkloe Fly Away Home by Eve Bunting For the Good of the Earth and Sun by Georgia Heard Grandfather Twilight by Barbara Berger How Many Days to America? By Eve Bunting If you Listen by Charlotte Zolotow Miss Maggie by Cynthis Rylant Mother Earth, Father Sky by Jane Yolen Oliver Button Is a Sissy by Tomie dePaola The Royal Bee by Frances Park and Ginger Park Something Beautiful by Sharon Dennis Wyeth Where Are You Going, Manyoni? By Catherine Stock Winter Fox by Catherine Stock (This is a list generated by Debbie Miller. It is printed in her book Reading with Meaning p.121 http://www.readingrockets.org/strategies/inference How and Why Characters Change Lesson Plans and Graphic Organizer http://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/inferring-characters-change858.html?tab=3#tabs http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson858/change.pdf Character Traits Inference Activity https://learnzillion.com/lessons/936-infer-and-cite-evidence-of-character-traits Inferencing Handbook-Full of strategies http://www.rainbowschools.ca/virtual_library/teacher_resources/support/Making-Inferencesbooklet-On-Target.pdf It Says I Say So… http://www.readingrockets.org/pdfs/inference-graphic-organizer.pdf Pre-made Inference Worksheets with reading passages http://www.ereadingworksheets.com/free-reading-worksheets/reading-comprehensionworksheets/inferences-worksheets/ Inference Observations occur when we can see something happening. In contrast, inferences are what we figure out based on an experience. Helping students understand when information is implied, or not directly stated, will improve their skill in drawing conclusions and making inferences. These skills will be needed for all sorts of school assignments, including reading, science and social studies. Inferential thinking is a complex skill that will develop over time and with experience. Why teach inference? Inference is a complex skill that can be taught through explicit instruction in inferential strategies Inferring requires higher order thinking skills, which makes it a difficult skill for many students. How to teach inference One simplified model for teaching inference includes the following assumptions: We need to find clues to get some answers. We need to add those clues to what we already know or have read. There can be more than one correct answer. We need to be able to support inferences. Marzano (2010) suggests teachers pose four questions to students to facilitate a discussion about inferences. What is my inference? This question helps students become aware that they may have just made an inference by filling in information that wasn't directly presented. What information did I use to make this inference? It's important for students to understand the various types of information they use to make inferences. This may include information presented in the text, or it may be background knowledge that a student brings to the learning setting. How good was my thinking? According to Marzano, once students have identified the premises on which they've based their inferences, they can engage in the most powerful part of the process — examining the validity of their thinking. Do I need to change my thinking? The final step in the process is for students to consider possible changes in their thinking. The point here is not to invalidate students' original inferences, but rather to help them develop the habit of continually updating their thinking as they gather new information. One model that teachers can use to teach inference is called "It says, I say, and so" developed by Kylene Beers (2003). Click below to see graphic organizer examples fromGoldilocks and the Three Bears, as well as the steps to solving a math problem about area and diameter. See graphic organizer example > When to use: Before reading During reading After reading How to use: Individually With small groups Whole class setting Examples Language Arts The Question-Answer Relationship strategy helps students understand the different types of questions. By learning that the answers to some questions are "Right There" in the text, that some answers require a reader to "Think and Search," and that some answers can only be answered "On My Own," students recognize that they must first consider the question before developing an answer. See Question-Answer Relationship strategy > Into the Book has an interactive activity that helps young children learn about inferring. In the interactive, students try to infer meaning in letters from virtual pen pals. They try to answer two questions: "WHERE is your pen pal?" (inferences about location) and "WHO is your pen pal?" (inferences about personality). Students search for clues in the text, then choose from three possible inferences for each clue. See virtual pen pal interactive > See virtual pen pal teacher guide > (click "Online Activity Teacher Guide") Riddles are one way to practice inferential thinking skills because successful readers make guesses based on what they read and what they already know. The object of this online riddle game is to infer what is being described by the clues you read. See riddle game > BrainPop offers several activities for teaching inference, and they offer resources for teachers and parents. See inference activities > Because so many stories contain lessons that the main character learns and grows from, it is important for students to not only recognize these transformations but also understand how the story's events affected the characters. This lesson from ReadWriteThink uses a think-aloud procedure to model how to infer character traits and recognize a character's growth across a text. Students also consider the underlying reasons of why the character changed, supporting their ideas and inferences with evidence from the text. See lesson plan > Math The Math Standards from the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) identify standards for PreK-12 students that include developing and evaluating inferences and predictions that are based on data. For young students, the standards specifically state the following: Pre-K–2 Expectations: In pre-K through grade 2, all students should discuss events related to students' experiences as "likely" or "unlikely." Grades 3–5 Expectations: In grades 3–5, all students should propose and justify conclusions and predictions that are based on data and design studies to further investigate the conclusions or predictions. Science Science teachers spend time helping students develop their observation skills. Inferring and observing are closely related, but they are not identical. Observation is what one sees, inference is an assumption of what one has seen. Observation can be said to be a factual description, and inference is an explanation to the collected data. It's not a guess. If an observation can be termed as a close watch of the world around you through the senses, then inference can be termed as an interpretation of facts that has been observed. Teachers can start out providing simple observations: Observation: The grass on the playground is wet. Possible inferences: It rained. The sprinkler was on. There is morning dew on the grass. Observation: The line at the water fountain is long. Possible inferences: It's hot outside. The students just came in from recess. As you're working to develop these skills, encourage your students to incorporate their scientific vocabulary into their statements. "From what I observe on the grass, I inferthat…" Learn more about how to use inference, and other science process skills, to help students understand our water resources. More on science process skills > This strategy guide from Seeds of Science introduces an approach for teaching about how scientists use evidence to make inferences. The guide includes an introductory section about how scientists use evidence to make inferences, a general overview of how to use this strategy with many science texts, and a plan for teaching how scientists gather evidence to make inferences. See teaching inference strategy guide > This lesson from ReadWriteThinkuses science to engage students in the process of making inferences. First, students work through a series of activities about making inferences. Then they read a booklet of descriptions of a series of mystery objects that are placed under a microscope. Finally, they look through each microscope and use the formula of schema + text clues = inference to make their own inferences about the identity of each mystery object. See science lesson plan > Social Studies In this Teacher Guide from the National Portrait Gallery at the Smithsonian, students use clues in a portrait to infer things about George Washington and his life. They work to identify visual clues the artist used, they compare various portraits of George Washington, and discuss the importance of the different portraits as visual records. See teacher guide > Often, inferring is introduced to students by using familiar symbols, activities, and environments from which they automatically draw inferences or make predictions (an inference about the future). For example, suppose you are about to begin a unit on the Great Depression. You might have students view a picture of the exterior of a mansion and then of a soup line. Then, through questioning, students focus on details, making inferences about the people who live in both places, their socioeconomic status, the kinds of food they eat, the kinds of activities they pursue. Parents can help to build these skills at home. For ideas to share with parents, see our Growing Readers tip sheet, Making Inferences and Drawing Conclusions (in English and Spanish). See parent tip sheet > Differentiated instruction for second language learners, students of varying reading skill, students with learning disabilities, and for younger learners Use graphic organizers like the It says, I say, So one to make the steps from observation to inference more explicit. Model the observation to inference process over and over again, using as many real-life examples as possible. Recognize that the background knowledge upon which inferences are drawn will be different for each student. Reassure students that answers can be different, but all should be made based on some sort of collected data. See the research that supports this strategy Beers, Kylene. (2003). When kids can't read: What teachers can do. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Gregory, A.E., & Cahill, M. (2010, March). Kindergartners Can Do It, Too! Comprehension Strategies for Early Readers. The Reading Teacher, 63(6), 515-520. Harvey, Stephanie, & Goudvis, Anne. (2000). Strategies that work (pp. 277-281). York, ME: Stenhouse. Marzono, R. (2010). Teaching inference. Educational Leadership, 67(7), 80-01. Available online at http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/apr10/vol67/num07/TeachingInference.aspx. Ozgungor, S., & Guthrie, J. T. (2004). Interactions among elaborative interrogation, knowledge, and interest in the process of constructing knowledge from text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(3), 437-443. Children's books to use with this strategy Looking Down by Steve Jenkins From high above, readers journey from space to earth with a progressively closer view though always looking down. What viewers are seeing changes with each page turn and may yield interesting inference on a number of levels (e.g., what else might one see from space?). Nurse, Soldier, Spy: The Story of Sarah Edmonds, A Civil War Hero by Marissa Moss , illustrated by John Hendrix This lively picture book biography of a woman who disguised herself as a man during the Civil War introduces a time in U.S. history and a bit of women's history. There are inferential thinking opportunities in either subject. (For example: From Sarah's experiences, what can be inferred about women's status in the 19th century? What can be inferred about the status of slaves when one young enslaved man tells Sarah he can't use cash money?) I See Myself by Vicki Cobb , illustrated by Julia Gordon Brief text and clear illustration combine to present both information and experiments that will encourage "what if" and "what next" discussions that can comfortably and safely combine with activities appropriate for young children. Chalk by Bill Thomson Join three children who find a magical piece of chalk that begins an exciting series of events to figure out "what next." This might be fun to use in conjunction with Crockett Johnson's Harold & the Purple Crayon(HarperCollins). Deep in the Forest by Brinton Turkle A baby bear explores a human abode in this riff on the Goldilocks tale. Readers could infer seasons, feelings, and consequences in this modern classic. What Do You Do with a Tail Like This? by Steve Jenkins , illustrated by Robin Page Clear, textured illustrations of animals and their special parts (e.g., tail, nose) focus readers on the special function of each. Not only is it likely to generate a description of the appendage but its function (what it does), and of the animal and its environment. Other books by Steve Jenkins, such asBiggest, Strongest, Fastest, may also generate rich descriptive language. The Little Plant Doctor: A Story About George Washington Carver by Jean Marzollo , illustrated by Ken Wilson-Max George Washington Carver was always curious and grew into a recognized scientist in spite of the challenges of the time in which he lived. His life and accomplishments become accessible to younger children through the voice of a tree planted by young George, augmented by child-like full color illustrations. Pop! A Book About Bubbles by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley , illustrated by Margaret Miller Have you ever wondered why bubbles are round? And why they pop? These and other questions are asked and answered in accessible language and crisp, full color photographs. Many easy-todo science activities are suggested (to be done with adult help). If America Were a Village: A Book About the People of the United Statesby David Smith , illustrated by Shelagh Armstrong (Kids Can, 2009) If all of the 300 million people were simply one village of 100 people, its diversity is easier to understand. That's just what the author has done to make the complex make-up of the U.S. residents (in terms of languages spoken, ages, and more). Colorful illustrations accompany the understandable text. Additional resources complete the book. If the World Were a Village: A Book About the World’s People, also by Smith, looks at the inhabitants of the world as a village to allow its diversity to become more understandable for adults and children. Wave by Suzy Lee (Chronicle) No words are needed to share a child's seaside adventure as she plays with the waves, is knocked down by one, and then discovers the sea's gifts brought to shore by the wave. Softly lined wash in a limited color palette evoke a summer afternoon on the beach. Pancakes for Breakfast by Tomie de Paola (Harcourt) On a cold morning, a little old lady decides to make pancakes for breakfast, but has a hard time finding all of the ingredients. This wordless picture book tells a story of determination and humor, ideal for young readers who can narrate the story as they Question-Answer Relationship (QAR) The question–answer relationship (QAR) strategy helps students understand the different types of questions. By learning that the answers to some questions are "Right There" in the text, that some answers require a reader to "Think and Search," and that some answers can only be answered "On My Own," students recognize that they must first consider the question before developing an answer. Why use question–answer relationship? It can improve students' reading comprehension. It teaches students how to ask questions about their reading and where to find the answers to them. It helps students to think about the text they are reading and beyond it, too. It inspires them to think creatively and work cooperatively while challenging them to use higher-level thinking skills. How to use question–answer relationship 1. Explain to students that there are four types of questions they will encounter. Define each type of question and give an example. Four types of questions are examined in the QAR: o Right There Questions: Literal questions whose answers can be found in the text. Often the words used in the question are the same words found in the text. o Think and Search Questions: Answers are gathered from several parts of the text and put together to make meaning. o Author and You: These questions are based on information provided in the text but the student is required to relate it to their own experience. Although the answer does not lie directly in the text, the student must have read it in order to answer the question. o On My Own: These questions do not require the student to have read the passage but he/she must use their background or prior knowledge to answer the question. 2. Read a short passage aloud to your students. 3. Have predetermined questions you will ask after you stop reading. When you have finished reading, read the questions aloud to students and model how you decide which type of question you have been asked to answer. 4. Show students how find information to answer the question (i.e., in the text, from your own experiences, etc.). http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/lesson_images/lesson151/guide.pdf Inferring Name_________________________________________________________ *Read these sentences and figure out what the underlined words mean. 1. I looked out the window and was surprised to see the snow. The sun was shining and the snow glistened. It looked like there were millions of diamonds on the ground. Glistened means ______________________________________________ What words helped you figure it out? 2. John and Jerry were running down the hall. They knew it was against the school rules. Mrs. May the principal stopped then and reprimanded the boys for running in the school. Reprimanded means _____________________________________________ What words helped you figure it out? 3. My tumbling teacher taught me to do a back flip and the splits. She said that I was very flexible. It was easy for me to bend backwards. I could go down in the splits without any trouble. Flexible means ________________________________________________ What words helped you figure it out? Inferring Name ___________________________ *Read this passage: Pat sat at the front of the table with a big smile on his face. His family and friends sang a song to him. Then he blew out seven candles on the cake. After they ate the cake, Pat opened the presents that everyone had given him. He said that this was his favorite day. He thanked everyone as they left. *After reading this passage, list 3 things that you inferred about what was happening. 1.____________________________________________________________________ 2.____________________________________________________________________ 3.____________________________________________________________________ What words helped you figure out what was happening? *You Be the Detective Ken reached into his pocket and took out some change. He stood in front of the machine and looked at the lighted buttons. Then he inserted the coins into the slot and pushed one of the buttons. When a can fell down into the dispenser, Ken took it out, pulled up the ring on the top of the can with his finger, and then put the can to his lips. What is Ken doing? Circle the correct answer. 1. Ken was buying a candy bar at the grocery store. 1. Ken was buying a meal at a fast food restaurant. 1. Ken was buying a can of pop from a vending machine. What words helped you figure out what he was doing? Inferring Name___________________________________________________ *You be the Detective Jerry scooped up a handful of snow and packed it into a ball. Then he put it down on the ground and began to push it around the yard. The snowball got bigger and bigger. Then Jerry made another ball and repeated the procedure. The second ball was smaller than the first. Jerry and his brother lifted the second snowball on top of the first one. They put an even smaller one on top of that. Then Jerry got some stones, a carrot, and a knitted scarf and put it onto the top snowball. *What was Jerry doing? Circle the correct answer. 1. He was having a snowball fight. 2. He was building a snowman. 3. He was snowboarding. What helped you figure out what Jerry was doing? *Read the passage. Joe went into the garage and got a bucket. He filled it with water and added soap. Then he got a sponge and dropped it into the bucket. He carried the bucket of soapy water outside and set it down. Then he took the sponge and began wiping it against his father’s car. When he was done with the sponge, he took the garden hose and rinsed off the soapy water. Then he put the hose, bucket and sponge away. *What was Joe doing? Circle the correct answer. 1. He was washing the sidewalk. 2. He was washing the car. 3. He was washing his bike. Write down five words that helped you infer what Joe was doing. ______________________________________________________________________________ Inferring Name _______________________________________________ *Read this passage Brandon’s mother pushed him in a chair with wheels on it down a sidewalk. There were cages along the sidewalk. She pushed his chair up to one of the cages. Brandon looked at the monkeys. They were acting very funny and making lots of noise. Down the sidewalk a little ways they saw a tiger. He was growling. Brandon told his mother that he was having fun. He wanted to come back again. *List 2 things that you inferred about Brandon and where he was. *What helped you figure out where Brandon was? *Read this passage. The room was very small. Karl sat in a chair facing a window. The window had a hole in it to talk through. He was wearing a uniform. When it was evening, the people walked up to the window and ask Karl for something. He would ask them if they wanted one for an adult or a child. They would give him some money and he would give them what they asked for. From where Karl was sitting he could smell the popcorn as it popped. He could see the people buying the popcorn. He liked working here. *From this passage what did you infer about Karl and what he was doing? *What words helped you figure out what Karl was doing? Inferring Name______________________________________________ *Read these sentences and figure out the meaning of the underlined word. 1. I was so excited because it was Christmas Eve. I walked down the stairs and peered into the front room. I could see the Christmas tree lights and all the presents that Santa had left for us. Peered means to ________________________________________________________ What words helped you figure it out?__________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________ 2. My friend fell and broke his leg. It was urgent that he be taken to the hospital. The ambulance came very fast and soon he was on his way. Urgent means _____________________________________________________________ What words helped you figure it out? 3. We hurried to the bus to find a seat. We looked around and all the seats were occupied. There were already many people standing. We didn’t know what to do. Occupied means _____________________________________________________________ What words helped you figure it out? ______________________________________________________________________________ Name___________________________________________________ Inferring for meaning with poetry _____________________________________________________________________________ I am a ______________________ ___________________________ I swim in the sea, Flipping and shining. ___________________________ Can you see me? Now you do ___________________________ And now you don’t Try and catch me- ___________________________ You won’t, you won’t! I jump in the air ____________________________ And feel so free, Twisting and turning ____________________________ Can you see me? Now you do, _____________________________ And now you don’t Try and catch me- ______________________________ You won’t, you won’t ______________________________________________________________________________ I am inferring that _____________________________________________________________ (Debbie Miller – “Reading with Meaning” page 114) Inferring We are learning about inferring as a comprehension strategy proficient readers use to better understand their reading. _____________________________________________________________________________ Book “Where Are You Going Manyoni” by Catherine Stock _____________________________________________________________________________ We predict she is going . . . _____________________________________________________________________________ We inferred unknown words like. . . _____________________________________________________________________________ Word What we infer its meaning What helped us 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. _____________________________________________________________________________ What did we learn? (Debbie Miller – “Reading with Meaning” page109)