Piracy is perhaps the oldest international crime. It was the first, and

T HE P ENALTIES FOR P IRACY :

A N E MPIRICAL S TUDY OF N ATIONAL P UNISHMENT FOR I NTERNATIONAL C RIME

R OUGH D RAFT FOR PRESENTATION AT H AIFA U NIVERSITY

D O NOT CITE W / OUT PERMISSION

By Eugene Kontorovich

*

ABSTRACT

This Article examines the sentences imposed by courts around the world in prosecutions of Somali pirates captured on the high seas. Somali piracy has become perhaps highest-volume area of international criminal law by national courts prosecuting extraterritorial crimes. As with other international crimes, international law is silent on the subject of penalties. With piracy, the large number of parallel prosecutions of offenders from a single international “situation” offers an empirical window into the interactions between international and national law in municipal courts; into factors affecting punishment for international crimes and the hierarchy of international offenses; and of course into potential concerns with the current model of punishing piracy.

Using a new data set of all Somali piracy sentences in foreign courts, the Article finds that the global average sentence for piracy is just over 14 years, comparable to the average penalties for more serious human rights offenses in international courts. Yet few pirates receive the “average” sentence. The

Article finds massive variance in sentences imposed in Somali pirate cases around the world, ranging from four years to life for substantively similar conduct. There are roughly two kinds of sentencing jurisdictions – lenient and strict. The former includes European countries, the latter primarily the

United States and Asian states. The gulf in sentencing between these two rough groups is quite significant. Finally, regression analysis of particular sentencing factors shows that the particular characteristics do not contribute significantly to the variance in sentences. Most variation that can be accounted for can be attributed the characteristics of the prosecuting state.

The empirical results suggest that there can be an international consensus about a crime’s international illegality without a corresponding consensus on the severity or magnitude of the crime. It also suggests that the distributed prosecution of a single international criminal situation across multiple municipal courts raises potential problems of inequity for similarly situated defendants. This may be an inevitable consequence of a lack of an international tribunal, but it also suggests the challenges of establishing one.

1.

Introduction

* Professor, Northwestern University School of Law. The author thanks Jon Bellish, and Gregory Barr and Benjamin Spulber of Northwestern University’s Searle Center for their invaluable assistance, as well as the Institute for Advanced Studies in

Princeton, where he was a member in the 2011-12, for a convivial environment.

1

Long considered an anachronism, piracy suddenly emerged as one of the most pressing international security and criminal law challenges, lead by a surge in activity and operational scope by

Somali-based pirates starting in 2007.

With little fanfare, many countries around the world have taken to prosecuting Somali pirates captured on the high seas. Twelve nations on four continents have convicted them, with numerous other cases pending. Prosecutions for this international law crime have become a worldwide effort, and have reached levels unprecedented in modern times. To be sure, piracy still mostly goes unpunished, as suspects captured by foreign navies are typically summarily released due to evidentiary difficulties and the relatively high costs of trials.

1

Still, in terms of the number of defendants prosecuted outside their home country, piracy has quickly become perhaps the thickest part of the international criminal docket.

Thus Somali piracy prosecutions offer a unique empirical insight into the actual workings of international criminal justice, and in particular, the interaction of international criminal law and domestic legal systems.

While the outlawing of piracy by international law is well established, international law provides no standard for the appropriate punishment. This paper finds massive cross-national variance in sentences for Somali pirates. To be sure, one would not expect prosecutions of an international crime in different national courts to result in equivalent sentences. Yet with Somali piracy, the parallel proceedings in multiple countries involve a common pool or class of offenders, for similar conduct within a single geopolitical context. A lack of a “minimum of uniformity and coherence in the sentencing of international crimes” for similarly-situated defendants raises basic questions of fairness.

2

Some commentators argue that such uniformity is even required across different courts prosecuting international crimes.

3

Even holding issues of equity aside, the sentences raise the question of what is driving the variance in punishment, as well as the normative question of the optimal approach to pirate punishment, from the perspective of retribution, deterrence, and vertical equity with other international crimes.

This Article presents an empirical study of worldwide sentencing for Somali pirates captured and tried outside of Somalia. It assembles an original dataset of all Somali pirate sentenced outside of

Somalia through 2012, and provides a preliminary statistical examination of the factors affecting the sentencing. Thus it responds to repeated calls for empirical research on international criminal law and sentencing.

4

The paper contributes to the understanding of the legal regime for piracy by identifying a previously unappreciated problem of significant sentence variance in current prosecutions of Somali defendants and exploring its causes. Sentence inequities will likely grow as more nations try and convict pirates, yet thus far the burgeoning literature on piracy ignored the sentencing issue.

5 It also provides

1 See Eugene Kontorovich & Steven Art, An Empirical Examination of Universal Jurisdiction for Piracy 104 A M .

J.

I NT

’

L L.

436 (2010).

2 Barbora Holá, Alette Smeulers & Catrien Bijleveld, International Sentencing Facts and Figures: Sentencing Practice at the

ICTY and ICTR , 9 J I NT

’

L C RIM .

J UST . 411, 439 (2011); cf. Antonio Cassese, The ICTY: A Living and Vital Reality, 2 J. I NT

’

L

C RIM .

J UST . 585, 596 (2007).

3 James Meernik, Sentencing Rationales and Judicial Decision Making at the International Criminal Tribunals , 92 S OC .

S CI .

Q. 588, 600 (2011).

4 M ARK A.

D RUMBL , A TROCITY , P UNISHMENT , AND I NTERNATIONAL L AW 2-5 (2007); Gregory Shaffer & Tom Ginsburg, The

Empirical Turn in International Legal Scholarship, 106 AM. J.. INT’L L. 1, 30 (2012); Ralph Henham, Developing

Contextualized Rationales for Sentencing in International Criminal Trials: A Plea for Empirical Research , 5 J.

I NT

’

L C RIM .

J UST .

757 (2007).

5 For example, a recent symposium issue of the Journal of International Criminal Justice devoted to piracy makes no mention of sentencing considerations. See Maggie Gardner, Piracy Prosecutions in National Courts, 10 J. Int. Crim. Just. 797, 821

(2012) (suggesting that other there are few difficulties of international concern in national prosecutions other than correctly applying international law).

2

important descriptive information about the prevalence of universal jurisdiction and other important factors about the global piracy docket.

The paper also contributes to the small but growing empirical literature on sentencing for international crimes.

6

Sentencing for international crimes has long been criticized as inconsistent, lax and generally incoherent – an “afterthought” to the imperative for prosecution.

7

Unlike much of the recent literature, which has mostly focused on international tribunals, we find a significant degree of variance that cannot be explained by the characteristics of the offense.

8

This is particularly relevant to discussions of implicit hierarchies among international crimes.

9

Empirical studies of ICTY and ICTRY have found that sentences reflect an implicit severity-based hierarchy of crimes.

10 This raises the question of what kind of international crime piracy is – it is more like robbery and other “ordinary” crimes,” or more like war crimes, torture and other international offenses. Moreover, the evidence about pirate sentencing suggests that there can be an international consensus about the crime’s international illegality without a corresponding consensus on the severity or magnitude of the crime. The Article also contributes to the literature on the implantation of international law by domestic courts. Piracy prosecutions illustrate the tensions between broad, uniform international norms and varied domestic penal regimes.

Part 2 begins by explaining why sentence variance may be particularly problematic in the Somali piracy context. Part 3 sketches the history of punishment for piracy. Part 4 gives on overview of global sentencing for piracy and introduces the dataset of pirate convictions. Part 5 discusses the average sentences, variances among countries, and other salient aspects of the data. Part 6 examines the factors discussed by courts in their sentencing opinions to see the range of factors that could contribute to the sentencing variance. Part 7 reports the results of a linear regression exploring both offense and forum effects on sentences, and then uses a multiple regression to see if these factors explain variance across cases. Part 8 discusses the results and their implications for counter-piracy efforts and international criminal theory more broadly.

2. The problem of sentences variance

Significant cross-national variance in punitivity for most common crimes has been repeatedly documented.

11

Given that baseline variance, and pirate sentencing takes place in multiple separate municipal systems, it bears considering why any variance here could be seen as surprising or potentially problematic. Because piracy is an international crime, one might expect some centripetal tendency in

6 See Shaffer & Ginsburg, supra

7 See Drumbl, supra note 3, at 11.

8 See e.g., Meerik, supra note

Hola et. al., supra

9 See Margaret M. deGuzman, Gravity and the Legitimacy of the International Court, 32 F ORD .

I NT

’

L L.

J. 400 (2009);

Allison Marston Danner, Constructing a Hierarchy of Crimes in International Criminal Law Sentencing, 87 Va. L. Rev. 415

(2001).

10 Kimi L. King and James D. Meernik, Assessing the Impact of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former

Yugoslavia: Balancing International and Local Interests While Doing Justice, at 22-25, in T HE L EGACY OF THE

I NTERNATIONAL C RIMINAL T RIBUNAL FOR THE F ORMER Y UGOSLAVIA , B ERT S WART , ET AL ., EDS . (2011).

11 Punitivity measures include percentage of population incarcerated, percentage of crimes prosecuted, conviction rates, sentences given and sentenced served, and various combinations. See Alfred Blumstein, Michael Tonry, & Asheley Van Ness,

Cross-National Measures of Punitiveness, 33 C RIME & J USTICE 347 (2005); Stefan Harrendorf and Paul Smit, Attributes of criminal justice systems: resources, performance and punitivity, in I NTERNATIONAL S TATISTICS ON C RIME AND J USTICE , S TEFAN H ARRENDORF , ET .

AL ., EDS ., at 113, 128 (2010).

3

sentencing; the theory of international crime might also suggest some degree of uniformity would be normatively desired. States that prosecute pirates under international law enforce not their own municipal law, but rather a law and a jurisdiction shared in common with the world. For universal jurisdiction crimes, national courts act as agents of the international legal order.

12

This is not simply a fanciful turn of phrase, but a legal reality. This can be seen from the fact that for non-international crimes, countries generally adhere to some version of the multiple sovereignties principle. If a single act violates the laws of multiple nations, each one that has jurisdiction can prosecute separately and cumulatively.

13

For example, an America who engages in child prosecution abroad could be prosecuted both in the U.S. and the foreign country without violating the international double jeopardy norm, known as non bis in idem . Yet non bis applies to piracy and other universal jurisdiction crimes 14 :

Robbery on the seas is considered an offence within the criminal jurisdiction of all nations. It is against all, and punished by all; and there can be no doubt that the plea of autre fois acquit would be good in any civilized State, though resting on a prosecution instituted in the Courts of any other civilized State.

15

Thus the major disparities in sentences for Somali pirates can be viewed as if they were variations within the courts of a single legal system for the exact same crime. Thus a group of similarly situated offenders from the same nation, engaged in the same course of conduct, and violating the same international law, face significantly variable punishment under international law depending on the place of prosecution.

Similar disparities in international criminal sentencing have raised concerns. It has been repeatedly noted that the median and mean sentences in the International Tribunal for the Former

Yugoslavia are considerably lower than in the Rwandan Tribunal,

16

even though the ICTY and ICTR operate under entirely different charters and are thus as much separate legal universes as two different nations. Moreover, the charter of each Tribunal adopts as a sentencing factor the sentencing practice for serious crimes in the domestic Yugoslavia and Rwanda respectively, thus building in some disparity.

17

Furthermore, while both charters include the same international offenses, the proportion of defendants charged with particular crimes varies considerably, with the ICTY having a larger war crimes docket, and the ICTR seeing a much higher proportion of genocide cases, generally thought to be more egregious crimes.

18

Still, commentators have suggested that such disparate punishment poses problems of equity amongst defendants. Similarly, the ICC has suggested that its sentences should take into account those of other international tribunals, even though they are entirely distinct judicial entities. The

12 See Quincy Wright, War Criminals, 39 A M .

J.

I NT

’

L L. 257, 280, 282 (1945).

13 See generally Eugene Kontorovich, Implementing Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain : What Piracy Teaches About the Limits of the

Alien Tort Statute, 80 N OTRE D AME L.

R EV . 111, 142-44 (2004). If doubled jeopardy barred such multiple prosecutions, defendants could seek out the most lenient jurisdiction and get off with a slap on the wrist. See United States v. Lanza, 260

U.S. 377, 385 (1922).

14 Lang Report, supra note 2, at 34.

15 United States v. Furlong, 18 U.S. 184, 197 (1820).

16 See Mark A. Drumbl & Kenneth S. Gallant, Sentencing Policies and Practices in the International Criminal Tribunals ,

15 F ED .

S ENT

’

G R EP .

140, 142 (2002); Mark B. Harmon & Fergal Gaynor, Ordinary Sentences for Extraordinary Crimes, 5.

J.

I NT

’

L C RIM .

J UST . 683 (2007).

17 International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia Statute, S.C. Res. 827, U.N. Doc. S/RES/827 (May 25, 1993);

Statute of the International Tribunal for Rwanda, S.C. Res. 955, U.N. Doc. S/RES/955 (Nov. 8, 1994).

18 Hola, et al., supra

4

sentencing equity problem is even more acute for piracy, where the offenders are charged with the same crime and have the same rank or level of organizational responsibility.

As with the separate charters of the tribunals, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

(UCNLOS), which codifies the international law of piracy, suggests the inevitability of some sentencing disparities in piracy prosecutions, by providing that the courts of the capturing state shall “decide” on the penalties.

19 Yet jurisdictional arbitrage by capturing states magnifies concerns about cross-forum inequities. Some of the pirate prosecutions in the dataset involve defendants that attacked the forum nations’ vessel. Yet the majority of convicted Somalis were captured by a vessel of one nationality

(typically European or American), and sent for trial in the courts of a third nation, usually in the region.

For most defendants, the sentencing forum is not determined merely by the accident of capture.

Consider a case where pirates were captured by France, but transferred for trial to the Seychelles. Such a transfer doubles the defendants’ expected sentence, from an average sentence of seven years in French courts, to 14 in the Seychelles. Conversely, when the U.S. transfers pirates to Kenya, it greatly reduces their expected sentence, from life in prison to roughly nine years. Disparate national sentencing practices mean that such transfers are no longer simply tools of convenience and expedience, but measures with substantive and predictable penal implications and consequences.

This forum shopping is noteworthy because UNCLOS only speaks of prosecution by the courts of the nation that captures the pirates, not by third-party transferees. Arguments have been made that

UNCLOS does not authorize such transfers. As the Lang Report notes, Art. 105 does not establish a general universal jurisdiction, but rather one limited to the “jurisdiction of the state that carried out the seizure.” 20

However, sate practice has clearly taken UNCLOS’s language as permissive.

21

Yet even if

Art. 105 permits such transfers, evidence of systematic sentencing disparities provides another way of thinking about such action. There is evidence that captors select place-of-trial fora not just with an eye to geographic convenience, but also to the kind of justice and punishment they will receive.

22

The existence of sentencing disparities suggests that these choices have a predictable and significant impact on defendants.

3. Background.

Piracy is perhaps the oldest international crime. It was the first, and for centuries the only, universal jurisdiction offense. Throughout the 18 th

and 19 th

centuries, execution was the presumptive international punishment. Indeed, the availability of the death penalty was one of piracy law’s salient features. As nations began to narrow or abolish the death penalty, it became impossible to treat it as the default punishment for piracy. The United Kingdom, perhaps the world leader in suppressing piracy,

19 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea art. 106, Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397.

20 Lang Report, supra note 2, at 22, § 48. However, the Lang Report does go on to praise transfer-for-trial agreements, without discussing their compatibility with the limited jurisdictional grounds he had previously mentioned. See id.

, pg. 25, §

65.

21 See Eugene Kontorovich, “ A Guantanamo on the Sea”: The Difficulties of Prosecuting Pirates and Terrorists , 98 C ALIF .

L.

R EV . 234 , 270-72 (2010); but see Tullio Treves, Piracy, Law of the Sea, and Use of Force: Developments off the Coast of

Somalia , 20 E UR .

J.

I NT

’

L L. 399, 402 (2009).

22 E UROPEAN U NION C OMMITTEE , C OMBATING S OMALI P IRACY : THE EU' S N AVAL O PERATION A TALANTA : E VIDENCE , 2009-

10, H.L. 103, at 14 (U.K.) (recording parliamentary testimony of U.K. Minister of State for Africa, Asia and the United

Nations that transfer to Kenya served deterrent purposes because the “pirates . . . would probably prefer a British prison” to a

Kenyan one).

5

abolished the death penalty for simple piracy in 1837, after the last major wave of piracy had abated;

23 the U.S. followed suit in 1897

24

When piracy was codified in the Law of the Sea Treaty in 1956, appropriate penalties were simply not mentioned.

25

Before the surge in Somali piracy and subsequent international response, there were few if any international law prosecutions of piracy.

26

But even these scant cases demonstrated the massive variance in penalties across countries. China became the world leader in such prosecutions during a crackdown in the late 1990s and early 2000s. China exemplified the harsh approach to punishment: in a series of four or five cases, it imposed the death penalty in two of them, at one point executing 13 pirates.

27

These cases appear to be the only use of the death penalty for piracy against foreigners under international law in recent decades. While China handed down these harsh sentences, India had also launched a thenunusual UJ prosecution of Indonesian pirates for taking the Japanese-owned Alondra Rainbow . This case took the opposite approach to China’s, sentencing the defendants to seven years in prison.

28

The first international law prosecution of Somali pirates took place in 2006, when the U.S.S.

Churchill captured a group attacking an Indian bulk carrier. After some discussions, Kenya agreed to try the suspects., As number of piratical attacks increased, more nations sent Somalis to neighboring Kenya for trial.

29

When that nation soured on the arrangement, the international community turned to the

Seychelles, and then other regional states to accept pirates captured by multinational forces. At the same time, various European and other nations tentatively stepped into the gap, bringing some Somalis back to their courts, particularly in cases where their own ships had been attacked.

23 Britain retained the death penalty for “piracy with violence,” which involves assault or attempted murder, until the total repeal of capital punishment in 1998.

24 See Act of Jan. 15, 1897, ch. 29, 29 Stat. 487 (1897). Hard labor was dropped in 1918, leaving the current mandatory life sentence.

25 The question of penalties simply did not arise during the years of discussions of the proposed treaty. See Report of the

International Law Commission to the General Assembly , 11 U.N. GAOR Supp. No. 9, U.N. Doc. A/3159, reprinted in [1956]

2 Y.B. Int’l Law Comm’n 253, at 283, U.N. Doc. A/CN.4/SER.A/1956/Add.l (“The Commission did not think it necessary to go into details concerning the penalties to be imposed and the other measures to be taken by the courts.”).

26 See Eugene Kontorovich & Steven Art, An Empirical Examination of Universal Jurisdiction for Piracy 104 A M .

J.

I NT

’

L L.

436 (2010).

27 Keyuan Zou, New Developments in the International Law of Piracy, 8 C HINESE J.

I NT

’

L L. 323, 342-44, n. 83 (2009) (“In comparison with trials in other countries, the punishment imposed by Chinese courts is the most severe.”); see also Zhu

Lijiang, The Chinese Universal Jurisdiction Clause: How Far Can it Go?

, 52 N ETH .

I NT

’

L L.

R EV . 85 (2005). In another case, the pirates received sentences of 10-15 years.

28 India Shows the Way in Piracy Battle , A SIA T IMES (Feb. 27, 2003), http://www.atimes.com/atimes/South_Asia/EB27Df01.html. The sentence was ultimately thrown out on appeal.

29 EU Nval Force Welcomes Ruling on Piracy in Kenya , H IIRAAN O NLINE (Oct. 1, 2010), http://www.hiiraan.com/news2/2010/oct/eu_nval_force_welcomes_ruling_on_piracy_in_kenya.aspx (eleven pirates sentenced to five years in prison in fourth Kenyan conviction); Kenyan Piracy Court Sentences Seven Somali Pirates to Five

Years in Jail , R EPUBLIC OF K ENYA (Sept. 8, 2010), http://republicofkenya.org/2010/09/_kenyan_piracy_court_sentences_seven_somali_pirates_to_five_years_in_jail/ (seven

Somali pirates sentenced to five years for attacking German vessel); Somali Pirates Sentenced to Five Years in Kenya , BBC

N EWS (Sept. 24, 2010, 9:47 AM), http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-11407176 (reporting sentence for seven pirates in attack on Maltese-flagged merchant ship Anny Petrakis); NTVKenya, 8 Pirates Handed 20-year Jail Sentence , Y OU T UBE

(Mar. 11, 2010), http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ej7mkOkLIRs.

Similarly, Yemen has prosecuted a group of pirates captured by the Russian navy after attacking an Iranian vessel; they faced

5-10 year terms.

6

4. The Data

The available data on international Somali pirate convictions consist of 406 sentenced defendants, and 78 distinct sentences.

30

The cases come from 14 different countries outside of Somalia. Prosecutions by Somali courts have been excluded for several reasons.

31

First, trials in the defendant’s home country may not raise the same issues of horizontal equity that foreign proceedings do. Moreover, such trials do not implicate international law to the same extent, in that the defendants were presumably not arrested on the high seas, where enforcement jurisdiction depends on international law. Moreover, the practical problems with the Somali convictions are overwhelming. There is little or no information on the details of these cases or on the sentences imposed, and there is some question whether prison sentences are actually being served. Indeed, it is not even clear if the reported Somali convictions involve the high seas, though again, the details are vague. This is crucial: piracy under international law must take place on the high seas – this is the essence of the offence.

32

Maritime robbery in territorial waters is not an international crime. In recent decades, most maritime depredation has been within territorial waters.

Because this is a study of international law, care was taken to only include actually piracy cases, with unclear cases determined by reference to news accounts and geopositional data on the attack from international maritime organizations and patrolling naval forces. As a result, the total number of convictions for piracy under international law examined here is significantly lower than the numbers reported by UNDOC and widely cited elsewhere.

33

The data does not differentiate the relatively few plea bargains from convictions after trial.

Moreover, it only reflects the original sentenced imposed at the trial level, without regard to subsequent appeals, because many cases still have pending appeals, and because the availability and nature of appellate review varies across jurisdictions. Similarly, the sentence length in the data refers only to the nominal sentence, without taking into account different nation’s laws about automatic or common sentence reductions, early release and so forth.

34

It should ben noted that 21 suspects have been acquitted (three in two French trials, one in the U.S. and 17 in one Kenyan proceeding), and several more released as underage. Thus globally, defendants selected for prosecution had a 95% conviction rate.

Pirate defendants often claim to be minors, and such claims are not always fully investigated by the prosecuting nation. The conviction data includes those sentenced as juveniles, though the age range of that offenses varied.

Some additional notes about the data. The prosecutions were selected by the nature of the crime, not the formal charges. Usually the defendants were charged with piracy, but in many jurisdictions they would instead be charged with comparable domestic crimes, like robbery and hijacking, because the prosecuting nation lacked a specific international piracy statute. There is nothing to suggest that these differences in nomenclature affected outcomes, and even in jurisdictions such as Italy and Germany where the defendants were formally charged with maritime robbery or kidnapping, they cases were

30 The data comes from 37 separate cases. Typically, pirate crews are tried and sentenced as a group, with all defendants receiving identical sentences. However, sometimes members of a pirate crew receive differential sentences reflecting differences in level of responsibility, age, cooperation, and similar factors.

31 The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, which coordinates international assistance to regional nations prosecuting piracy, reports in its newsletters that over 300 defendants convicted by the various regions and breakaway entities of Somalia.

The UNODC however has little information in these cases beyond those raw numbers, which were reported by local Somali officials.

32 See UNCLOS Art. 101(a)(1).

33 UNDOC also counts several Omani and Yemeni cases as piracy despite their taking place in territorial waters.

34 The one exception is Spain, where the defendants received consecutive sentences on multiple charges that, in aggregate, exceeded the country’s overall maximum prison term.

7

discussed as piracy cases, and the international law of piracy invoked by the courts. Furthermore, in some cases defendants were also convicted of additional charges arising out of the same crime, such as weapons charges, or those relating to violence against military personnel. These additional charges are ignored here, and in any case, sentences on multiple counts were concurrent.

Obviously the data should be approached with caution. Two nations account for nearly half the sentences, and most countries that have convicted pirates have only done so in one or two cases.

International prosecution of Somali pirates is still a new phenomenon, and the existing data may not be predictive of future trends. Numerous cases are pending, including several new nations, such as India, with more than 100 suspects in custody.

35 Moreover, the universe of prosecuted cases is itself highly selected, and not representative. By most accounts, many if not most captured pirate suspects are released without trial due to the difficult in promptly finding a willing forum to prosecute. Many of the same nations that have prosecuted pirates have also been prominent practitioners of the so-called “catchand-release” policy. Thus the variance in convictions is on the background of broad uniformity in decisions about whether to prosecute. Moreover, prosecution outside of the Seychelles or Kenya is almost always driven by the suspects’ involvement on an attack on a vessel with strong ties to the prosecuting nation. Thus prosecuted cases contain a much smaller share of universal jurisdiction cases relative to the universe of apprehended pirates.

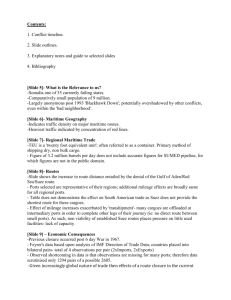

Table 1A. Somali Piracy Sentences in Foreign Courts

35 Julia Zappei, Somali Pirates Face Death Sentences in Malaysia , T HE J AKARTA G LOBE (Feb. 11, 2011), http://www.thejakartaglobe.com/home/somali-pirates-face-death-sentences-in-malaysia/422152; Somali Pirates Could Face

Prosecution in Malaysia, South Korea , C HANNEL N EWS A SIA (Jan. 26, 2011, 2:58 AM), http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/afp_asiapacific/view/1106905/1/.html.

8

Mean Sentence Length, by Country

U ni te d

St at es

Sp ai n

U

AE

So ut h

Ko re a

Se yc he lle s

Ke ny a

Be lg iu m

Ye m en

Ita ly

Fra nc e

G erm

N et he rla nd s

M ad ag as ca r

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Table 1B. Number of defendants

Number of defendants by country

Amount of defendants by country

5. Basic Features of Pirate Sentencing

This section will outline some of the key features of the data. The high and low sentences for similar acts of piracy by Somalis tried as adults spans the entire spectrum of possible sentences, from 4 or 5 years in Kenya and Holland to life in the U.S. The data reveals a sharp bifurcation between “lenient”

European jurisdictions and the U.S. and a few other nations. Table 1 lists all sentences, while Table 2 indicates the national averages sentence.

9

The worldwide mean sentence across the 406 defendants is 14.2 years, slightly less on a per defendant basis.

36

There is a massive variance across sentences. The standard deviation in sentences is also 13.6 years – almost equal to the mean. Excluding the U.S. cases, which are dominated by life sentences, the mean sentence drops to 11.8 years, and the standard deviation to

9.7 years. Thus even with U.S. cases to one side, there is significant variance in jail terms across nations, though clearly the U.S. is driving much of the global variance.

country with the largest pirate docket has mean of mean adult sentence is 16.4 years, and a mean including juveniles of 13.6,close to the global average. Kenya’s mean sentence is 8.3 years (but also just above 11 on a per defendant basis). These two nations have convicted the most pirates, and applied sentencing norms that seem stricter than Europe but less severe than the U.S.

European penalties are well below the global average.

The data also show that the choice by capturing states between domestic prosecution and transfer to Kenya or the Seychelles has significant penal consequences. Moreover, the choice between transferring to Kenya or Seychelles has punitive implications, with sentences in the latter being on average more noticeably more severe.

The numbers show piracy has quickly become the largest branch of international criminal law.

The ICTY and ICTR have both sentenced slightly more than 60 defendants ( and acquitted 10 each).

37

In a few years, Kenya and the Seychelles have sentenced almost as many international criminals as each of the tribunals in their nearly two decades of operation. This is not to compare the gravity of the offenses involved, or the complexity of the proceedings. It does suggest that piracy as an international crime is one of unprecedented volume – the international criminal equivalent of street crime - and this volume will raise particular challenges that have not been fully address or even conceptualized.

Piracy is, on average, punished under international law as severely as some of the gravest international crimes. Thus worldwide mean sentence for piracy is comparable to the average sentence of the ICTY (16 years), which prosecuted war crimes, ethnic cleansing and other serious international crimes. However, worldwide pirate sentences are significantly less than those imposed by the ICTR, because of the latter’s extensive use of life sentences.

38 The mean pirate sentence internationally also approximates the average penalties imposed by the East

Timor and Kosovo international tribunals.

39

It is also approximately half of the International

Criminal Court’s presumptive maximum sentence for the “most serious crimes of international concern.”

40

At the same time, given the variance in sentences, in practice pirates are being punished either much more leniently or severely than serious international criminals before international tribunals.

36 Life sentences are difficult to account for in sentencing studies. Max M. Schanzenbach & Emerson H. Tiller,

Strategic Judging Under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines: Positive Political Theory and Evidence ,

23 J.L.

E CON .

&O RG . 24, 35 n.34 (2007). In this study they have been somewhat arbitrarily converted to a 60 year sentence for data purposes, because of the youth of the defendants. See James Meernik, Sentencing Rationales and Judicial Decision

Making at the International Criminal Tribunals , 92 S OC .

S CI .

Q. 588, 601 (2011).

37 Key Figures , ICTY – TPIY, http://www.icty.org/sections/TheCases/KeyFigures (last updated Feb. 3, 2012); Status of

Cases , I NTERNATIONAL C RIMINAL T RIBUNAL FOR R WANDA

– UNICTR, http://www.unictr.org/Cases/tabid/204/Default.aspx

(last visited June 3, 2012).

38 Even for non-life terms, the average ICTR sentence is almost 25 years.

39 Mark A. Drumbl, Collective Violence and Individual Punishment: The Criminality of Mass Atrocity , 99 N W .

U.

L.

R EV .

539, 557-58 (2005).

40 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Arts. 1, 77 (1998) 2187 U.N.T.S. 90.

10

Universal jurisdiction prosecutions for piracy remain the exception, and focused in a few nations.

Slightly more than half of the cases (but a significant majority of defendants) were convicted in universal jurisdiction cases.

6. Sentencing factors discussed in court opinions.

This section will examine the kind of qualitative factors courts have identified as relevant to pirate sentencing.

41

Most of the factors are present in almost all of the cases, such as the young age of the pirates, or the severe economic harm of their crimes. Unlike with other international crimes, piracy involves a relatively narrow range of conduct. At the same time, differences in sentencing statutes and policies would at first glance explain much of the variance across jurisdictions. This is clearest in the

U.S. example, where a life sentence is both the mandatory minimum and maximum sentence. Indeed, piracy punishments are severe even by American standards. While the U.S. is an outlier in its punitive severity, life sentences are quite uncommon in the federal system,

42

and mandatory minimum life sentences for first-time convicts are reserved for aggravated murder.

43

Similarly, European countries tend to have significantly lower maximum penalties for piracy (for example, 15 years in Germany; 12 in

Holland, or 15 when lethal force is used; in Italy 14, or 20 for the captain). By contrast, Seychellois and

Kenyan maximum sentences are 30 years and life, respectively.

Kenya’s sentences are particularly low in relation to its statutory maximum. And even in nations with relatively low maximum sentences, the maximum penalties are generally not imposed. Prosecutors typically sought much stiffer sentences than those imposed.

44

In other words, it does not appear that jurisdictions with higher ranges strive for convergence by sentencing leniently, or that those with lower ranges seek global convergence by impose the relatively lengthy ones. Indeed, national courts explicitly refer to past sentences of Somali pirates in their own jurisdiction as benchmarks, but make no mention of sentences in other nations, even in universal jurisdiction cases.

Despite the disparity in outcomes, national courts take into account similar aggravating and mitigating circumstances. Some of these circumstances are quite ordinary, and largely invariant across cases. Courts consider the youth of the defendants, their status as (presumably) first-time offenders, and the desperate circumstances in Somalia.

45 One conceptual question relates to how to treat the abstract gravity of the crime of piracy - as ordinary robbery that happens to fall within international criminal law

41 The discussion is based on written opinions and official summaries in cases from the Kenya, Seychelles, Holland, Spain,

Germany and the United States. Information on other jurisdictions is less extensive and comes from news reports or, in some cases, academic reports.

42 In 2009, for example, only 0.3% of federal defendants sentenced by a judge received life terms.

43 Despite the mandatory sentence in the piracy statute, there is nothing mechanistic about these sentences. They cases result from a combination of the defendants not pleading guilty and from a policy decision by the U.S. Attorney to press piracy charges in addition to the numerous other indictable counts.

44 Alice Baghdjian, German Prosecutor Urges Jail in Somali Piracy Trial , R EUTERS (Jan. 25, 2012, 6:32 PM), http://uk.reuters.com/article/2012/01/25/uk-germany-pirates-idUKTRE80O22U20120125; Somali Pirates Plead Innocence in

Paris Trial , R EUTERS (May 22, 2012, 3:16 PM), http://af.reuters.com/article/topNews/idAFJOE84L0AG20120522; Pirates somaliens du Carré d’As: appel du parquet de Paris, vers un nouveau procès , L’E XPRESS .

FR (May 12, 2011, 4:07 PM), http://www.lexpress.fr/actualites/1/societe/pirates-somaliens-du-carre-d-as-appel-du-parquet-de-paris-vers-un-nouveauproces_1058123.html.

45 There has been some discussion of pursuing pirate ringleaders and financiers with greater severity. Sentencing practice in the ICTY and ICTR supports the notion that sentence length should be related to the leadership role of the defendant. Given that with the exception of one U.S. case, all the defendants in this study have been “foot soldiers” rather than masterminds, there is no reason to think that prosecuting states would not impose relatively stiffer sentences for the latter, were they to get them into custody.

11

because of the locus of the crime, or as part of a serious threat to international security and order. Courts have adopted the latter approach. Thus a Dutch court noted the steep increase in pirate attacks since

2008, and concluded that “piracy is now a serious threat to the internationally acknowledged right to free passage in international waters.” 46

Similarly, the Seychellois courts have observed in sentencing that “we must not forget that the enormity of the threat that piracy poses to maritime enterprise is phenomenal and has the potential to disrupt international law, order and maritime security environment at sea, which in turn impacts on the international system of trade.”

47

Seychellois courts have also spoken of “the adverse effects of this offence on humanity.” A Kenyan court has said, “Piracy in this region has become a menace… this calls for a deterrent sentence.” 48

The legal definition of piracy encompasses everything from speeding towards a targeted ship and attempting to board, to firing at it, successfully boarding and taking hostages, or even abusing or injuring the crew or rescuers. The international law definition of piracy includes attempts rather than treating them as less or preparatory offenses, but one might still expect the difference between inchoate and consummated offenses to be reflected in sentencing. Indeed, sentencing opinions suggests attacks are considered as more severe the further they progress. Courts also discuss the level of violence used as an aggravating circumstance.

Some sentencing considerations relate directly to the exercise of universal jurisdiction. Universal jurisdiction is thought to be a hallmark of the seriousness of an international crime. De minimis non curat lex might be particularly true of international criminal law; one might a nation’s decision to exercise universal jurisdiction to suggest something about the seriousness of the crime.

49

Perhaps surprisingly, some courts have mentioned this as a mitigating factor, because it involves incarceration in a country far from the defendant’s home, and with which one has no previous ties.

50

Even in universal jurisdiction cases, some fora will have a greater nexus with the crime than others, and this can impact sentencing. Thus Seychellois courts specifically take into account, as an aggravating factor, the significant impact of Somali piracy on their nation’s economy, which has seen tourism and fishing revenues drop sharply.

51

7. Causes of variance – case or country attributes?

52

As has been seen, pirate sentences vary massively across nations. This could be caused either by differences in the cases themselves – granular facts about the particular pirate attacks – or by difference among the sentencing jurisdictions, or some combination of the two. The existence of sentencing

46 Rb Rotterdam [District Court of Rotterdam], 17 June 2010, NJFS 2010, 230 m.nt. (Neth.) [hereinafter Samanyolu ], translation available at http://www.unicri.it/maritime_piracy/docs/Netherlands_2010_Crim_No_10_6000_12_09%20Judgment.pdf, at 12.

47 Republic of Seychelles v. Ahmed, (Criminal Side No. 21 of 2011) [2011] (30 June 2011) (Sey.) [hereinafter Gloria ], available at http://www.unicri.it/maritime_piracy/docs/Seychelles_2011_Crim_No_21%20(2011)%20Sentence.pdf, at 2.

48 Republic of Kenya v. Ahmed (2010) (K.C.M.C.) (Kenya) [hereinafter MV Powerful ], available at http://www.unicri.it/maritime_piracy/docs/Kenya_2010_Crim_No_3486%20(2008)%20Judgment.pdf, at 30.

49 See Mark Drumbl, The Charles Taylor Sentence and Traditional International Law (June 11, 2012), available at http://opiniojuris.org/2012/06/11/charles-taylor-sentencing-the-taylor-sentence-and-traditional-international-law/ (discussing the Sierra Leone Tribunal’s use of the extraterritorial nature of the crime as an aggravating factor).

50 Samanyolu , supra note 43, at 12; Gloria, supra note 44.

51 Hon. Mr. J. Duncan Gaswaga, Head of Criminal Div., Supreme Court, Sey., Presentation at the Judicial Learning Exchange

Program: National Experiences and Challenges in Prosecuting Piracy Cases: Seychelles (Dec. 2011).

52 NOTE FOR HAIFA WORKSHOP: the discussion in the remainder of the paper is based on an earlier 305 observation, 12cuontry data set; I have just finished updating the data above, but have not rerun the analysis on it.

12

variance does not it itself show that like cases receive different punishments in different jurisdictions.

Thus recent empirical literature on sentencing in international criminal tribunals suggests that differences in the particulars of cases accounts for much of the apparent difference in severity between the ICTY and ICTR. This section will test the hypothesis that offense attributes, rather than country attributes, explain the variance.

To explore the possible effects of state-based factors, 11 country dummy variables were used, with Seychelles as the index country, because it has the largest number of prosecutions, and its mean sentence is close to the global mean. (The results remain similar but weaker when other index states were used.) To explore case-based effects, each conviction was coded for three independent binary variables - success (vs. attempt), violence, and universal jurisdiction. Success is a binary variable with a value of 1 when the attack succeeds in taking control of the target vessel for any period, and zero when it fails, either because the pirates never made it on board or because they were stopped by naval and security forces before they took control of the ship. While there is no separate international law crime of

“attempted” piracy, attempt generally captures less serious crimes – the crew has not been held hostage, and far less economic harm has been done to the owners (26 observations are coded as success).

Violence is 1 when the defendants fired directly at the crew or at rescue forces, assaulted the crew, or engaged in particular psychological tortures (17 observations are coded as violent). (To be sure, all pirate attacks are inherently violent; this variable seeks to capture aggravating degrees of violence.) To be sure, violence and success are somewhat collinear – the earlier an attack is terminated, the smaller the chances for violence, though suspected pirates often violently resist arrest. Universal jurisdiction is coded as 1 only for “pure” cases, where the prosecuting nation neither flagged nor owned/operated the victim vessel. The variable is used without expectations of significance, as universal jurisdiction prosecutions have been focused in only a few states.

The dependent variable is sentence length per defendant, expressed in years. Each defendant is an observation. For robust standard errors, data was clustered by vessel name.

VARIABLES violence success uj youth pros_france pros_germ pros_italy pros_kenya pros_madag

Table 2 – Causes of Pirates Sentences sentence sentence

-2.896*** -3.025***

(1.071) (0.984)

5.135*** 5.018***

(1.067)

-1.997*

(1.016)

-2.074*

(1.118) (1.084)

-5.352*** -5.380***

(1.204) (1.210)

-12.71*** -12.76***

(1.327) (1.312)

-7.824*** -7.980***

(1.269) (1.157)

-4.792*** -4.952***

(1.802)

-1.296

(1.715)

-1.318

(1.245) (1.236)

-9.618*** -9.457***

13

pros_nld pros_sk pros_spain pros_uae pros_us pros_yemen

Constant

Observations

R-squared

Number of groups

Number of pros2

(1.302) (1.205)

-8.167*** -8.183***

(0.889)

7.778

(0.899)

-1.413

(8.698) (1.310)

12.28*** 12.31***

(0.715) (0.715)

7.282*** 7.312***

(0.715)

40.94***

(0.715)

(2.129)

-10.28*** -10.33***

(1.352) (1.338)

14.58*** 14.74***

(1.242) (1.108)

305

0.822

285

0.519

Robust standard errors in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Type of Regression: OLS OLS

[with life sent.] [w/out life sentences]

N=305

53

N=285

The results suggest that the variance in outcomes depends heavily on the idiosyncrasies of prosecuting jurisdictions than the particulars of the offense or its status as an international crime. Eight out of the elven country dummies are significant, while none of the case-specific dummies are. These overall results are robust across multiple specifications of the model, though in some fewer countries are significant. The coefficient for success is positive, as one would expect, and close to significance.

54

Violence while not significant is also negative, and it bears noting that this variable has the crudest coding. Universal jurisdiction is consistently negative, but only three countries have had pure UJ cases, and they happen to be on average non-punitive states, so the negative sign may not be informative. With

UJ, decisions to not prosecute will absorb most of the reluctance to hear such case. The results suggest that the variance in sentences is not attributable to granular differences in the severity of the particular piracies, but rather to systemic differences in the punitive approach of the various fora. It is notable that almost all the negative country dummy coefficients are greater in absolute value than the juvenile dummy variable. The negative coefficient for almost all the significant country variables highlights the substantive effects of transfer to the Seychelles.

53 See prior note.

54 The insignificance of the success variable has a practical implication. The U.S. Supreme Court is currently being asked to reconsider whether unconsummated piracy really amounts to real “piracy” under international law. See United States. v. Dire,

680 F.3d 446 (May 23, 2012), petition for certiorari file Oct. 1, 2012). The data suggests an affirmative answer from state practice, in that attempt does not even appear to be a significant mitigating factor. Given that legal systems typically treat attempt less severely than completed offenses.

14

8. Discussion.

The notion of international crime presumes some normative consensus – that certain crimes are particularly grave, either morally or in their threat to international stability. Indeed, universal jurisdiction offenses are widely described as a jus cogens or fundamental norm, suggesting an added degree of transnational normative convergence. One might expect that this putative normative agreement would translate into some punitive convergence in sentencing, despite background punitive variances among countries. Yet this is not empirically observed. This suggests that the consensus about international criminality is “thin,” and raises questions about the nature of the consensus. Whether such variances would be found for other international crimes were they prosecuted in parallel in multiple national courts is of course an open question.

Choices about where to prosecute pirates – be it the courts of the captor, a regional nation that has specialized in such cases, or an international tribunal – have significant implications for the kind of sentences pirates will receive. While all these fora apply the same law, they do not apply the same penalties. The choice of forum has been generally approached based on feasibility and convenience, as a logistical or technical matter. The sentencing consideration – the ultimate goal of prosecution – has been largely absent from discussions of the optimal modalities for trying pirates.

Disparate sentencing for similar crimes raises questions of fairness, especially when the prosecutions are self-consciously being conducted as part of an international effort to suppress Somali piracy. The large variance in sentences across jurisdictions tends to weaken the deterrent value of such punishment by making it less predictable to potential pirates what kind of sanctions they might actual face. However, despite its apparent aberrancy, the current chaotic punishment system may be preferable to the alternatives. The lack of international criminal sentencing guideline is itself a consequence of the lack of consensus over such secondary issues. When a nation undertakes to “domesticate” international crimes, it expects to do so on terms similar to how it deals with other offenses. Nations have diverse penal norms, and do not like imposing punishments inconsistent with their “scale.” Domestic courts are likely to care as much or more about vertical equity (within the national criminal system) than horizontal

(international) ones.

Another implication of the disparities uncovered here is that there are costs to increasing the number of prosecuting states. While doing so obviously spreads costs, it comes at the perhaps inevitable expense of serious punitive inequities. For prosecutorial fora, more is not always merrier, especially as cost-spreading could be effected through more direct financial mechanisms.

A final implication concerns complementarity. A major principle of international law is complementarity: only when the nation with direct jurisdiction over the crimes is “unwilling or unable to genuinely prosecute” does enforcement evolve to the international level. The Rome Statute of the ICC incorporates complementarity in Art. 17, and it may be part of the customary international law of universal jurisdiction more generally. Yet one of the biggest open questions about ICC jurisdiction is how one determines when a nation that goes through the motions of prosecution and even sentencing is actually sham that triggers ICC jurisdiction. The complementarity question becomes even more difficult if the national court convicted and sentenced the defendant, in which case the court would have to conclude that the sentence was so light as to be designed to “shield[] the person concerned from criminal responsibility.” 55

.

55 Art. 20(3)(a).

15

Thus the complementarity question for a sentenced defendant essentially turns on whether the national punishment varies to some impermissible degree from what justice would require.

56

This in turn requires an understanding of the normal range of variance in sentences for a single international crime across different national jurisdictions. Thus the considerable variance among nations in sentencing piracy (which does not even have many of the sentencing variables in international criminal sentencing, such as significant differences in rank, mode of participation, scale of crimes, and so forth) suggests that significant cross-national differences are “expected” and a normal part of the system of dispersed multinational prosecution. Piracy shows that acceptable punishments for a particular crime can range from a few years to life in prison for similarly situated defendants. This suggests a previously underappreciated stumbling block for international criminal jurisdiction may not be nations that brazenly refuse to prosecute, but rather those that do choose to prosecute and apply the most lenient penal policies.

56 D’Ascoli at 13 & n. 9 (noting relevance of sentencing practices of national courts to determining “unwillingness” in cases where a national sentence seems quite light).

16