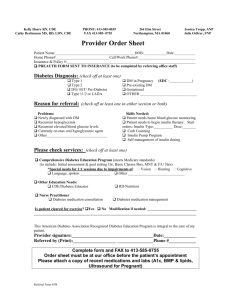

Stress Testing Pre Exercise

advertisement

Leading Health Indicators 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 7. 9. 10. Physical inactivity Overweight and obesity Tobacco use Substance abuse Responsible sexual behaviour Mental health Injury and violence Environmental quality Immunizations Access to health care US National Institute of Health Leading Health Indicators 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 7. 9. 10. Physical inactivity Overweight and obesity Tobacco use Substance abuse Responsible sexual behaviour Mental health Injury and violence Environmental quality Immunizations Access to health care US National Institute of Health Academy of Medical Royal Colleges UK Februray 2015 Heart Disease 40% Reduction Two-thirds of the burden of cardiovascular diseases can be attributed to the combination of diet and physical inactivity. Physical activity has a very strong effect in reducing the development of heart disease.17 Studies vary in quantifying the reduction in risk of heart disease as “up to 50%”, or “20 35% lower risk” of cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease. People who change from doing minimal activity to moderate activity have most to gain. Across a population, a move to active travel alone could reduce heart disease by 10%. Hypertension Exercising regularly reduces the risk of ever developing hypertension by 52%. Depresion Depression Lifetime risk 33% 50% Obese Patients Depressed Risk Reduction General Population30% There is a 20% to 33% lower risk of developing depression, for adults participating in daily physical activity Dementia 30% The evidence is fairly consistent in quoting reduced risks of developing dementia at “20-50%”. 20,35,77,78 Bowel Carcinoma 45% Reduction Physical activity has a very strong effect in reducing the occurrence of bowel cancer This is quantified at 30-50% lower risk. The 30 to 50% lower risk of colon cancer in men and women across 19 international studies was related to the beneficial effect of exercise on growth factors and insulin resistance Stroke 30% Reduction Different reports quote exercise as reducing the risk of stroke or of mortality from stroke by 20 - 40%. Osteoarthritis 50% Reduction Analysing several studies quantified the reduction in risk of developing arthritis by undertaking moderate exercise at between 22-83%. Risk of diabetes physical activity is proven to reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 50-80%. Diabetes – Numbers to Treat for Benefit 6.4 Lifestyle including PA 10 Medication but medication more side effects First 15 Minutes Exercise a day 416,175 people – average follow 8years 3 years increase in Life expectancy 15mins/day - 14% reduction all cause mortality Every extra 15 mins/day 4% extra < Mortality Chi Pang Wan et al Lancet Vol. 378-9798 1244-1253 Aug 2011 Exercise in non-diabetics Decreases insulin release Stimulates glucose transport into muscle Therefore, increase in insulin sensitivity 14 Exercise in non-diabetics Increases cortisol, catecholamines Increases glucagon Free fatty acids and liver glycogen to be mobilized for energy 15 BENEFITS OF EXERCISE Increase insulin sensitivity Decreased triglyceride Improved functional capacity Enhanced sense of wellbeing Reduced risk of CAD Reduced risk of MI Decreased ‘stickiness’ of blood platelets Reduced risk of High BP Can reduce high BP levels Increased HDL levels Decreased LDL levels Improved HDL / LDL ratio Decreased Body Fat Decreased risk of Osteoporosis Decreased risk of Diabetic associated complications Fitness and Incident Metabolic Syndrome; 9007 Men and 1491 Women Age-Adjusted Rate/1000 45 40 p<0.001,each 35 Middle 30 High Low 25 20 15 10 5 0 Men Women LaMonte M et al. Circulation. 2005; 112:505-512 Fitness and Metabolic Syndrome; 11,833 Patients with 3-Day Diet Records Odds of Metabolic Syndrome* 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 Thirds of CRF Low Moderate High Low intake *Adjusted for confounders, including macronutrient intake High intake Finley CE et al. JADA 2006; 106:673 Fitness and Incident Type 2 Diabetes; 8633 Healthy U.S. Men Diabetes incidence/1000 men 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Low Mod Cardiorespiratory Fitness High Wei M et al. Ann Int Med 1999 Fitness and Incident Type 2 Diabetes; 4747 Japanese Men; Tokyo Gas Company Relative risk adjusted for age and risk factors 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 I II III IV Level of Fitness Sawada SS et al. Diab Care 2003; 26:2918 All-Cause Mortality by Fitness Groups in 3,757 Men with Metabolic Syndrome Odds Ratio 3 2.5 p for trend <0.001 2 1.5 1 0.5 0 Low Moderate High Cardiorespiratory Fitness Groups Katzmarzyk et al. Arch Int Med 2004; 164:1092 Risk of cardiovascular disease mortality by cardiorespiratory fitness and body mass index categories, 2316 men with type 2 diabetes at baseline, 179 deaths. Blair S N Br J Sports Med 2009;43:1-2 ©2009 by BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine Fitness and Cancer; Mortality in 1744 Men with Diabetes Relative risk of Cancer Death * 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 p for trend =0.002 Low Moderate High Cardiorespiratory Fitness *Adjusted for age and risk factors Thompson AL et al. In progress Lifestyle-related Risk Factors and Risk of Future Nursing Home Admissions; 6462 Adults RiskFactor 45-64years HazardRatio(95%CI) Smoking 1.56(1.23-1.99) Inactivity 1.40(1.05-1.87) BMI≥30.0 1.35(0.96-1.89) HighBP 1.35(1.06-1.73) HighCholesterol 1.14(0.89-1.44) Diabetes 3.25(2.04-5.19) Valiyeva E et al. Arch Int Med 2006; 166:985 Peripheral Neuropathy brisk 1-hour walk on a treadmill four times a week slowed how quickly their nerve damage worsened Indications for Exercise Longevity Quality of Life Socialization Weight control Disease prevention Disease management ….(I could go on) Men Women No Physical Exercise During a 7-Day Period 40 37 33 Percent 30 27 20 26 27 21 21 21 18 17 10 0 14 11 1988 2002 18-34 1988 2002 35-54 1988 2002 55+ Slan Survey 1999 Percentage of respondents who reported no exercise in an average week Trend towards inactivity being reversed? Slan survey results reporting no exercise 30 25 28 23 19 20 % reporting no exercise 15 10 5 0 1998 2002 2007 Percentage of respondents who reported no exercise in an average week, by age, gender and year (1998, 2002 and 2007) % reporting moderate &/or strenous exercise 3 or more times per week for at least 20 mins 41 41 40 40 39 38 38 37 36 1998 2002 2007 Physical Inactivity is a global priority Global prevalence of physical inactivity 31% Irish prevalence of physical inactivity 60% As Presented by Prof. Fiona Bull, MBE at the NEHRF Expert Symposium in DCU on 19 th June, 2014 I think you’ll find it’s a bit more complicated than that Ben Goldacre, www.Bad Science.net Killing you softly and gently CC www.TheNounProject.com Components Activity Thermogenesis 2000 Kcal/day Thermal effect of food 1000 Kcal/day Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) 0 Kcal/day More detailed! 2000 Kcal/day Exercise 1000 Kcal/day Non Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) 0 Kcal/day Some arguments in favour of NEAT Circulation. 2007;116:1081-1093 Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006;26;729-736 20 females, BMI 32 8 weeks of low energy diet 500 kcal x 4w 850 kcal x 4 w 2 groups Exercise 3/w x 90 minutes No exercise Measured Average Daily and Sleeping Metabolic Rates Am J Clin Nutr 1995;62:722-9. Am J Clin Nutr 1995;62:722-9. What we thought would happen Exercise Exercise Non Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) Non Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) What really happened Exercise Exercise Non Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) Non Exercise Activity Thermogenesis (NEAT) Revising concepts is NEAT! Stable “Exercise” levels Obesity levels increase We do “more” with “less”(movement) NEAT decreases with inactivity. NEAT decrease may be the main factor in energy overload In cohorts of people who do not exercise Increased rates of DM CAD Obesity CANNOT BE CAUSED BY ADDITIONAL “EXERCISE” DEFICIENCY Diabetes 56:2655–2667, 2007 Showing 2 types of muscles, that react very differently to both Exercise Lack of movement (Sedentarism) Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2650-2656 Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle (AusDiab Study) 173 patient, underwent OGTT Accelerometer based Diabetes Care 30:1384–1389, 2007 Same population Relationship of sedentarism and Waist circumference 3.1 cm difference Cluster of metabolic risk factors Diabetes Care 31:369–371, 2008 Cross sectional study of 1921 children, 9-10 yold and 15-16 yolds Accelerometer based activity Self reported TV viewing Metabolic risk score TV viewing was NOT correlated with PA (r=0.013, p=0.58) PLoS Med 3(12): e488. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030488 Obes Res. 2005;13:608–614 Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., Vol. 41, No. 5, pp. 998–1005, 2009 Non Exercisers Even if you exercise, the effects are still there! Exercisers J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:292–9 Times that people spend sitting versus participating in exercise based leisure time physical activity are different classes of behavior with distinct determinants AND INDEPENDENT RISKS FOR DISEASE Different effects of sedentary behavior compared to “exercise” Metabolic and Mortality effects seen Through age groups Through ethnic groups Newer objective data seems to support larger self reported data Diabetes 56:2655–2667, 2007 Diabetes Care 31:661–666, 2008 IDLE Breaks Study Baker IDI Heart & Diabetes Institute Effects of acute bout of sitting time in post prandial Glc/Tg With and Without Breaks Unpublished Data Glucose Insulin Breaking news: New data All are statistically significative! Hot off the presses Treatment group burns 0.18 kcal/min more (17% more) 300 calories/week In obese/overweight group, increases to 0.38 kcal/min (32% more) 575 calories/week Am J Public Health. 2011 Mar 18. [Epub ahead of print] 7 Investments that work for physical activity 1. Whole-of-school’ programs 2. Transport policies and systems that prioritise walking, cycling and public transport 3. Urban design regulations and infrastructure that provides for equitable and safe access for recreational physical activity, and recreational and transport-related walking and cycling across the life course 4. Physical activity and NCD prevention integrated into primary health care systems 5. Public education, including mass media to raise awareness and change social norms on physical activity 6. Community-wide programs involving multiple settings and sectors & that mobilize and integrate community engagement and resources 7. Sports systems and programs that promote ‘sport for all’ and encourage participation across the life span What are the new findings? Outdoor walking groups have wide-ranging health benefits including reducing blood pressure, body fat, total cholesterol and risk of depression. Outdoor walking groups appear to be an acceptable intervention to participants, with high levels of adherence and virtually no adverse effects. Lifestyle Intervention: Physical Activity Results 74% of volunteers assigned to intensive lifestyle achieved the study goal of > 150 minutes of activity per week at 24 weeks The DPP Research Group, NEJM 346:393-403, 2002 Percent developing diabetes Incidence of Diabetes Placebo (n=1082)All Metformin (n=1073, p<0.001 vs. Placebo) Lifestyle (n=1079, p<0.001 vs. Met , p<0.001 vs. Plac ) Lifestyle (n=1079, , Metformin (n=1073,p<0.001 p<0.001vs. vs. Metformin Plac) Placebo (n=1082) p<0.001 vs. Placebo) Cumulative incidence (%) 40 30 participants Risk reduction 31% by metformin 58% by lifestyle 20 10 0 0 1 2 Years from randomization The DPP Research Group, NEJM 346:393-403, 2002 3 4 Intervention goals 5% reduction in initial weight Exercise ≥30 min/day Decrease fat to <30% of caloric intake Increase fibre to ≥15 g per 1000 kcal Decrease saturated fat to <10% of caloric intake Cumulative probability of remaining free of diabetes 1.2 1.1 1.0 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 Intervention group Control group 0 1 2 3 4 5 Study year 6 Tuomilehto et al. N Engl J Med 2001; 344: 1343–50 Cumulative probability of remaining free of diabetes 1Year intensive intervention 1.2 1.1 4 years 58% 1.0 7 years 43% 0.9 0.8 13years 38% 0.7 0.6 5 Years Delay in onset DM 0.5 0.4 0 SLtDddddddddddudy year Intervention group Control group 2 3 4 5 6 1 13year follow up Jan 2013 Weight Change (kg) Mean Weight Change 0 Placebo -2 Metformin -4 Lifestyle -6 -8 0 1 2 Years from Randomization The DPP Research Group, NEJM 346:393-403, 2002 3 4 Muscular Strengthening Exercise large muscle groups 8-12 reps; should fatigue by last rep Rest 2-3 minutes between exercises 1 set good, 2 sets better Rest day in between Resistance training prevention diabetes 32002 men – 18 years 150 minutes/week Resistance Training alone Aerobic Training alone Both Health Professional follow up study Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1306-1312. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3138 34% reduction 52% reduction 59% reduction Combined Training HbA1 DMtype2 Combined Training DM The prevalence of increases in hypoglycemic medications were 39% in the control, 32% in the resistance training, 22% in the aerobic, and 18% in the combination training groups with the Mantel-Haenszel test for linear association being significant (P = .005). The prevalence of decreases in hypoglycemic medications were 15% in the control, 22% in the resistance training, 19% in the aerobic, and 26% in the combination training groups (P = .20). The prevalence of individuals who achieved the composite outcome of either decreasing hypoglycemic medication or reducing HbA1c by 0.5% without increasing medications were 22% in the control group, 26% in the resistance training, 29% in the aerobic, and 41% in the combination training group Conducting exercise stress testing before walking is unnecessary. No evidence suggests that it is routinely necessary as a CVD diagnostic tool, and requiring it may create barriers to participation. ADA/ACSM November 2011 Pre-exercise evaluation Cardiac screening is controversial Decreased risk in DM of unexpected cardiac death who exercise 79% of perfusion abnormalities resolved 3 yrs with medical therapy If exercise treadmill +, poor prognosis Don’t know result of interventions Clin Sports Med 2009;28:379-92 Diabetes Care 2007;30:2892-8 76 Pre-exercise evaluation Asymptomatic Type II with + adenosine stress compared with non screened No reduction in cardiac events High risk Type II revascularization vs aggressive medical therapy No difference in long term mortality JAMA 2009;301:1547-55 NEJM 2009;360:2503-15 77 Stress Testing Vigorous For exercise more vigorous than brisk walking or exceeding the demands of everyday living, sedentary and older diabetic individuals will likely benefit from being assessed for conditions that might be associated with risk of CVD, contraindicate certain activities, or predispose to injuries, including severe peripheral neuropathy, severe autonomic neuropathy, and preproliferative or proliferative retinopathy Who to do stress test? Low to moderate intensity, good control, not many risk factors Start program Out of shape, starting program Start low to moderate intensity OR non-exercise imaging Handbook of Exercise in Diabetes 2002 Clin Sports Med 2009;28:379-92 79 Who to do stress test? If moderate to high intensity exercise AND/OR ADA guideline risk factors Autonomic neuropathy PVD, retinopathy + EKG Stress test OR modify risk factors prior to exercise Handbook of Exercise in Diabetes 2002 Clin Sports Med 2009;28:379-92 80 FACTORS WHICH PREVENT EXERCISE READYNESS TO CHANGE Health concerns Family commitments Work commitments Transport difficulties Weather Cost Security concerns Exercise Type II Exercise reverses deficits in metabolism Basal insulin HbA1c Basal glucose Liver glucose production Insulin stimulated glucose uptake GLUT4 receptors Insulin sensitivity Cholesterol, triglycerides GSSI #90 2003;16(3) 82 Exercise Benefits 20-30% reduction in HbA1c in Type II Decrease lipids Decrease blood pressure Weight loss and maintenance Reduce metabolic syndrome Reduce risk of CAD !! 83 Physical Activity and Mortality DM Total PA was associated with lower risk of CVD and total mortality. Compared with physically inactive persons, the lowest mortality risk was observed in moderately active persons: Hazard ratios were 0.62 (95% CI, 0.49-0.78) for total mortality and 0.51 (95% CI, 0.32-0.81) for CVD mortality. Leisure-time PA was associated with lower total mortality risk, and walking was associated with lower CVD mortality risk. In the meta-analysis, the pooled random-effects hazard ratio from 5 studies for high vs low total PA and all-cause mortality was 0.60 (95% CI, 0.49-0.73). Annals of Internal Medicine Online first August 2012 Borg perceived exertion scale 6 No exertion at all 7 Extremely light 8 9 Very light - (easy walking slowly at a comfortable pace) 10 11 Light 12 13 Somewhat hard (It is quite an effort; you feel tired but can continue) 14 15 Hard (heavy) 16 17 Very hard (very strenuous, and you are very fatigued) 18 19 Extremely hard (You can not continue for long at this pace) 20 Maximal exertion Borg perceived exertion scale Perceived Exertion Scale Level 1: I'm watching TV and eating bon bons Level 2: I'm comfortable and could maintain this pace all day long Level 3: I'm still comfortable, but am breathing a bit harder Level 4: I'm sweating a little, but feel good and can carry on a conversation effortlessly Level 5: I'm just above comfortable, am sweating more and can still talk easily Level 6: I can still talk, but am slightly breathless Level 7: I can still talk, but I don't really want to. I'm sweating like a pig Level 8: I can grunt in response to your questions and can only keep this pace for a short time period Level 9: I am probably going to die Level 10: I am dead METs 3.5-4 Moderate Walking at a brisk pace (1 mi every 20 min) Weight lifting, water aerobics Golf, not carrying clubs Leisurely canoeing or kayaking Walking at a very brisk pace (1 mi every 17 to 18 min) Climbing stairs Dancing (moderately fast) Bicycling <10 mph, leisurely METs 4.5-6 Moderately Vigorous Plus Slow swimming Golf, carrying clubs Walking at a very brisk pace (one mi every 15 min) Most doubles tennis Dancing (more rapid) Some exercise apparatuses Slow jogging (one mi every 13 to 14 min) Vigorous Exercise Hiking Rowing, canoeing, kayaking vigorously Dancing (vigorous) Some exercise apparatuses Bicycling 10 to 16 mph Swimming laps moderately fast to fast Aerobic calisthenics Singles tennis, squash, racquetball Jogging (1 mile every 12 min) Skiing downhill or cross country Why Resistance Training? Improves metabolism – proven reduction in Insulin Resistance, incidence of D.M., additive effect to aerobic exercise in prevention and treatment of IHD Improves muscle strength – less falls/#s Reduced Osteoporosis 1year increase BMD 1.3% Controls loss 1.2% Arthritis – Reduced pain Improved function Exercise that uses muscular strength to move a weight or move against a resistive load In diabetes resistance exercise of the major muscle groups on 2 non consecutive days in the week is recommended Resistance Training Resistance can be own body weight Press Up / Sit Up Light Weights – Dumb Bells Resistance bands Progression Over time and as the person achieves 3 sets of 10-15 reps the weight can be increased, as this produces impoved blood glucose effects As the weight increases the number of reps per set can be reduced to 8-10