beer_sub1

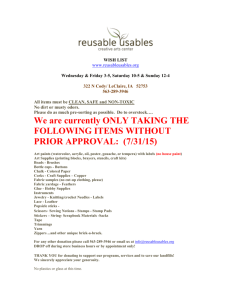

advertisement

Substitution between Mass-Produced and High-End Beers Daniel Toro-Gonzalez Ph.D. candidate, School of Economic Sciences (SES) Jill J. McCluskey Visiting Professor, Cornell University and Professor, SES, Washington State University and Ron C. Mittelhammer Regents Professor, SES & Dept. of Statistics Presented at Beeronomics Symposium UC Davis November 3, 2011 Macro Brews Dominate many U.S. Markets 2 However, This is Changing • Mass producers’ market share still represents the vast majority of sales, but their sales are flat or declining. • Trend of consumers switching from mass to craft beers. • Consistent with general shift in food preferences: Increasing desire for variety, taste, and local products. We know that consumers shift from macro to craft brews. Does it go the other way? • “…consumers are very loyal to craft beers and not shifting to macro from craft. In economics terms the cross-price elasticity of craft and macro brews appears to be very inelastic, or that beer drinker do not think of macro lagers as a good substitute for micro brews.” - “Beeronomics: Is Craft Beer Recession Proof After All ?” , The Oregon Economics Blog, Thursday, May 7, 2009. Project Objectives •Estimate demand for beer, which is a differentiated product. •Estimate the own-price, cross-price and income elasticities. Data • Scanner data from 60 Dominick's supermarkets in Chicago. • Seven years of store-level weekly sales data (1991 to 1997) • 483UPCs for 343 brands. • Product info and store area sociodemographics Market and Product Definition • Oligopolistic differentiated product market. • Each store is treated as an independent market. • Each brand of beer is considered as a product. Types of Beer 1. Mass produced beers are defined as those with similar characteristics of lightness, same fermentation method (bottom fermenting yeast) and the use of adjuncts such as corn or rice. 2. Import beers are those produced abroad. 3. The rest of the beers are called craft beers. 8 Number of Firms • Long term secular decline in traditional breweries • Rapid expansion in specialty breweries since 1980 Market Shares by Beer Type Sample Averages for Dominick Stores Type Craft Mass Import Share 5.3% 86.4% 8.2% Price Per Bottle 0.80 0.54 0.95 Discrete Choice Model Issues • Model weekly aggregate sales at each store, by beer type • Address dimensionality problem (large number of underlying products) by projecting the products onto a characteristics space. • Market characterized by differentiated products. • Prices may be correlated with unobserved demand factors, causing endogeneity problem. Discrete Choice Model • Utility of consumer i for product j depends on characteristics of both the product and the consumer: U ( x j , j , p j , vi , d ) Observed product characteristics, 𝑥𝑗 . Unobserved product characteristics, 𝜉𝑗 . Price, 𝑝𝑗 . Consumer characteristics,𝑣𝑖 . Demand parameters, 𝜃𝑑 . Observable Variables ( x j , p j , j ) Observed product characteristics: – Size of the bottle – Alcohol content – Type (Mass, Craft, Import) – Style (Ale, Fruit, Low Alcohol, Oktoberfest, Seasonal, Smoked, Steam, Stout, Wheat) Price Observed consumer characteristics: – Household income, home value, household size, education (% college graduates), ethnicity (% blacks+hispanics) Discrete Choice Model • Linear specification of utility uij z j p j j ij • where z j x j j • j is interpreted as the mean of consumers’ valuations of unobserved product characteristics (product quality). • Error term encompasses the distribution of consumer preferences around j . • Errors are i.i.d. with “extreme value” distribution, resulting in a multinomial logit formulation. Mean Utility Representation uij d j ij • Simply using dj to represent the mean utility for product j , which is defined as everything other than the error term: d j z j pj j Multinomial Logit • The market share of product j is then expressible in term of dj : s j (d ) e N δj e k 0 δk Multinomial Logit • Assuming the relationship between observed and predicted market shares is invertible, with the mean utility of the outside good (all other than beers) normalized to zero, ln( s j ) ln( s0 ) d j z j p j j • Prices and unobserved product attributes are correlated Endogeneity. Instrument for Prices • Prices in other markets? (Hausman, 1996). Prices of brand j in two markets will be correlated due to the common marginal cost. But prices in other markets uncorrelated with the market-specific unobserved product characteristics. Variable \ Method MNL Price -9.10E-06*** 0.000 Size 9.11E-06*** 0.000 Alcohol -2.63E-06*** 0.000 Craft -1.77E-05*** 0.000 Import -1.74E-05*** 0.000 Ethnic 8.22E-06 0.000 Education -2.51E-05 0.000 Household Size -7.90E-06 0.000 Incomes 6.85E-08 0.000 Observations 12066 R2 0.201 Legend: * p<.1; ** p<.05; *** p<.01. MNL-IV -0.283*** 0.012 0.054*** 0.002 0.029*** 0.010 -0.319*** 0.024 -0.202*** 0.026 0.139*** 0.047 0.217 0.155 -0.179*** 0.030 0.002*** 0.000 12066 0.438 MNL: Ignores endogeneity of prices. MNL-IV: Prices in other markets as IV for Price. Problem with MNL • Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA). Example, if a consumer wants to try a beer that is an American lager, he/she may consider alternatives like Coors light or Bud Light, but he will not consider any Stout type of beer. Nested Logit Model • The NL preserves the assumption that consumer tastes are extreme value distributed. • Allows consumer tastes to be correlated across products. • More reasonable substitution patterns than in the previous model (a priori). Nested Logit Model • We divide the products into g different exhaustive and mutually exclusive groups. u d (1 ) ij j jg ij d j z j pj j • is common to all products in group g. • (1-σ) is the average correlation in the random utility across products of the same group. Nested Logit Model • Berry (1994) shows that if the errors are i.i.d. extreme value then: jg (1 ) ij it is also distributed as a extreme value. Nested Logit Model • We can represent the NL model as: ln( s j ) ln( s0 ) d j z j p j ln( s j / g ) j where σ measures average similarity of products within each group of beer types. The new term is the log of the within group share. Variable / Method MNL Price -9.10E-06*** 0.000 Size 9.11E-06*** 0.000 Alcohol -2.63E-06*** 0.000 Craft -1.77E-05*** 0.000 Import -1.74E-05*** 0.000 Ethnic 8.22E-06 0.000 Education -2.51E-05 0.000 Household Size -7.90E-06 0.000 Incomes 6.85E-08 0.000 σ(Average across g) MNL-IV -0.283*** 0.012 0.054*** 0.002 0.029*** 0.010 -0.319*** 0.024 -0.202*** 0.026 0.139*** 0.047 0.217 0.155 -0.179*** 0.030 0.002*** 0.000 Observations R2 12066 0.438 12066 0.201 Legend: * p<.1; ** p<.05; *** p<.01. NL-IV -0.229*** 0.011 0.006*** 0.001 0.060*** 0.008 -5.253*** 0.040 -5.122*** 0.040 0.090*** 0.035 -0.130 0.110 -0.087*** 0.022 0.002*** 0.000 0.892*** 0.000 12066 0.716 Price Elasticities Mass Craft Import Mass -0.1223 0.0004 0.0002 Craft 0.0028 -0.3168 0.0013 Import 0.0004 0.0008 -0.1566 Over All Source: Dominik’s dataset, calculations by the authors. Over All -0.1715 Compare with Other Findings Source Price Elasticity Hogarty and Elzinga 1972 -0.889 Orstein and Hanssens 1985 -0.142 Tegene 1990 -0.768 Lee and Tremblay 1992 -0.583 Gallet and List 1998 -0.730 Nelson 1999 -0.200 Nelson 2003 -0.174 This study -0.172 Source: Table 2.2. Tremblay and Tremblay (2005). Income Elasticities Elasticity Mass 0.257 Craft 0.434 Import 0.460 Over All 0.260 Source: Dominik’s dataset, calculations by the authors. Price Elasticities: Other Findings Source Income Elasticity Hogarty and Elzinga 1972 0.430 Orstein and Hanssens 1985 0.011 Tegene 1990 0.731 Lee and Tremblay 1992 0.135 Gallet and List 1998 -0.545 Nelson 1999 0.760 Nelson 2003 -0.032 This study 0.260 Source: Table 2.2. Tremblay and Tremblay (2005). Conclusions • Demand for beer is inelastic with respect to prices. • Cross-price elasticities are very close to zero. Mass and craft beers are not close substitutes! • From the income elasticities, all of the types of beer (mass, craft, and import) are normal goods. Next Steps • Estimate the model using a random coefficients specification for utility. • Allow for consumer heterogeneity. • Consumer characteristics can interact with product attributes. • Examine other formulations/instruments to tackle endogeneity between price and unobserved product characteristics. Thank you and Cheers! Questions? (pictures from the Beeronomics Conference, Belgium May 2009)