Vocal communication between cows and calves in extensive range

advertisement

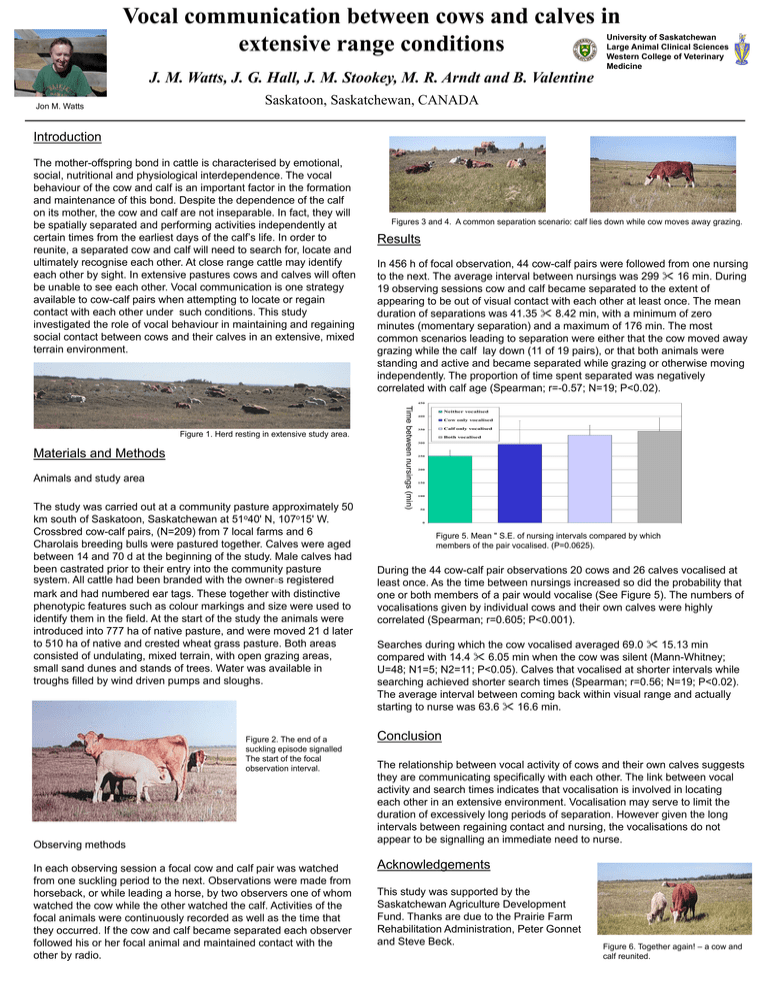

Vocal communication between cows and calves in extensive range conditions University of Saskatchewan Large Animal Clinical Sciences Western College of Veterinary Medicine J. M. Watts, J. G. Hall, J. M. Stookey, M. R. Arndt and B. Valentine Jon M. Watts Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, CANADA Introduction The mother-offspring bond in cattle is characterised by emotional, social, nutritional and physiological interdependence. The vocal behaviour of the cow and calf is an important factor in the formation and maintenance of this bond. Despite the dependence of the calf on its mother, the cow and calf are not inseparable. In fact, they will be spatially separated and performing activities independently at certain times from the earliest days of the calf’s life. In order to reunite, a separated cow and calf will need to search for, locate and ultimately recognise each other. At close range cattle may identify each other by sight. In extensive pastures cows and calves will often be unable to see each other. Vocal communication is one strategy available to cow-calf pairs when attempting to locate or regain contact with each other under such conditions. This study investigated the role of vocal behaviour in maintaining and regaining social contact between cows and their calves in an extensive, mixed terrain environment. Figures 3 and 4. A common separation scenario: calf lies down while cow moves away grazing. Results In 456 h of focal observation, 44 cow-calf pairs were followed from one nursing to the next. The average interval between nursings was 299 " 16 min. During 19 observing sessions cow and calf became separated to the extent of appearing to be out of visual contact with each other at least once. The mean duration of separations was 41.35 " 8.42 min, with a minimum of zero minutes (momentary separation) and a maximum of 176 min. The most common scenarios leading to separation were either that the cow moved away grazing while the calf lay down (11 of 19 pairs), or that both animals were standing and active and became separated while grazing or otherwise moving independently. The proportion of time spent separated was negatively correlated with calf age (Spearman; r=-0.57; N=19; P<0.02). 450 Materials and Methods Animals and study area The study was carried out at a community pasture approximately 50 km south of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan at 51o40' N, 107o15' W. Crossbred cow-calf pairs, (N=209) from 7 local farms and 6 Charolais breeding bulls were pastured together. Calves were aged between 14 and 70 d at the beginning of the study. Male calves had been castrated prior to their entry into the community pasture system. All cattle had been branded with the owner=s registered mark and had numbered ear tags. These together with distinctive phenotypic features such as colour markings and size were used to identify them in the field. At the start of the study the animals were introduced into 777 ha of native pasture, and were moved 21 d later to 510 ha of native and crested wheat grass pasture. Both areas consisted of undulating, mixed terrain, with open grazing areas, small sand dunes and stands of trees. Water was available in troughs filled by wind driven pumps and sloughs. Figure 2. The end of a suckling episode signalled The start of the focal observation interval. Observing methods In each observing session a focal cow and calf pair was watched from one suckling period to the next. Observations were made from horseback, or while leading a horse, by two observers one of whom watched the cow while the other watched the calf. Activities of the focal animals were continuously recorded as well as the time that they occurred. If the cow and calf became separated each observer followed his or her focal animal and maintained contact with the other by radio. Time between nursings (min) Figure 1. Herd resting in extensive study area. Neither vocalised 400 Cow only vocalised Calf only vocalised 350 Both vocalised 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 Figure 5. Mean " S.E. of nursing intervals compared by which members of the pair vocalised. (P=0.0625). During the 44 cow-calf pair observations 20 cows and 26 calves vocalised at least once. As the time between nursings increased so did the probability that one or both members of a pair would vocalise (See Figure 5). The numbers of vocalisations given by individual cows and their own calves were highly correlated (Spearman; r=0.605; P<0.001). Searches during which the cow vocalised averaged 69.0 " 15.13 min compared with 14.4 " 6.05 min when the cow was silent (Mann-Whitney; U=48; N1=5; N2=11; P<0.05). Calves that vocalised at shorter intervals while searching achieved shorter search times (Spearman; r=0.56; N=19; P<0.02). The average interval between coming back within visual range and actually starting to nurse was 63.6 " 16.6 min. Conclusion The relationship between vocal activity of cows and their own calves suggests they are communicating specifically with each other. The link between vocal activity and search times indicates that vocalisation is involved in locating each other in an extensive environment. Vocalisation may serve to limit the duration of excessively long periods of separation. However given the long intervals between regaining contact and nursing, the vocalisations do not appear to be signalling an immediate need to nurse. Acknowledgements This study was supported by the Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund. Thanks are due to the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration, Peter Gonnet and Steve Beck. Figure 6. Together again! – a cow and calf reunited.