pom_v16 - Princeton University

advertisement

Geophysical Fluid Experiments with the

Princeton Ocean Model

Lie-Yauw Oey

Princeton University

Page 2

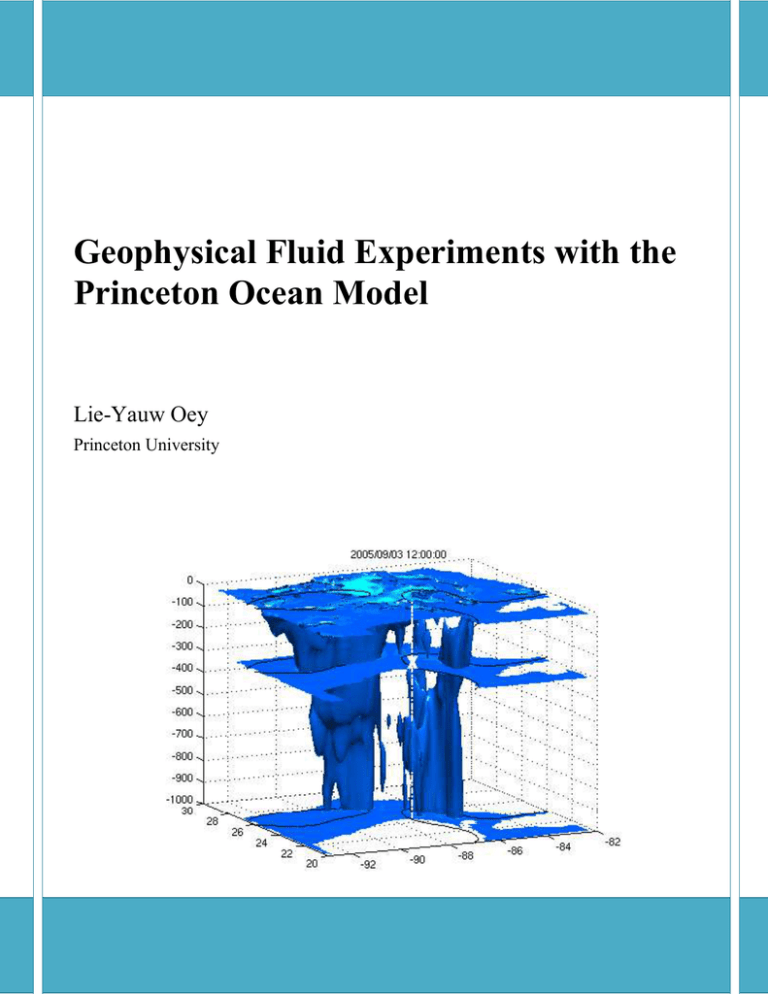

COVER ILLUSTRATION

A three-dimensional surface of near-inertial energy = 0.03 m2s-2 on Sep/03/12:00,

approximately one week after the passage of the disastrous hurricane Katrina, Aug/2530/2005, in the Gulf of Mexico, USA, simulated by the Princeton Ocean Model. This

shows penetration of intense energies to deep layers due to the presence of the warm-core

ring and the Loop Current, both represented by the dark contours in the three cut-away

xy-planes.

The location of an observational mooring where extensive modelobservational analyses have been conducted is shown as vertical dashed line [from: Oey

et al. 2008: “Stalled inertial currents in a cyclone,” in press, Geophysical Res. Lett., with

permission to reproduce].

Page 3

PROLOGUE: About This Book

“.. I have no special talents. I am only passionately curious..” (Albert

Einstein)

This book is about exploring various aspects of fluid motions on a

rotating earth using a popular, relatively simple yet powerful numerical

model - the Princeton Ocean Model (POM). It is a book aimed primarily

for advanced undergraduates and graduates in physical oceanography; but

the book should also be useful for researchers or anyone fascinated by and

intensely curious about oceanic fluid motions. Some knowledge of fluid

mechanics is assumed, equivalent to a two-semester course which usually

covers up to the derivations of conservation laws of viscous fluid motions,

including the boundary layer theory; these prerequisites should not be an

impediment to those interested enough to want to open this book. On the

other hand, we have strived to make the book more or less self-contained by

building each chapter from simple to more advanced concepts. By

conducting geophysical fluid experiments on a computer and analyzing the

results, we hope that the student will gain a solid understanding of

geophysical fluid dynamics (GFD) and physical oceanography; the student

will also learn to critically examine the results (be a skeptic) and to attempt

connecting them to the real-world phenomena. And of course, the student

will learn to use POM, numerical methods and, we hope, to keep exploring

long after he or she surpasses this book.

Why POM? One reason is our familiarity with the model. More

importantly, however, it is because the model is relatively easy to tweak, say

to suit a different flow problem, or to change the model physics. This

makes it an excellent educational tool because it gives the student a handson experience. It is much like the difference between being a driver and

being a driver as well as a mechanics. Most of us are the former, but only

the privileged few belong to the latter. POM shares many of the same

features of other popular ocean models now available in the scientific

community, and it uses basically the same equations of motions and

conservation of mass etc. Therefore, an accomplished student of this book

should find it easy to transit to other models should he or she so desire.

The book begins in chapter 1 with the near-surface ocean response to

wind built upon Ekman’s fundamental work. This is not the common

Page 4

approach of a book in physical oceanography. On the other hand, most of

us experience the ocean perhaps through a summer swim in a coastal sea or

in a lake, and wind-driven surface motions are the most apparent. For a

majority of flows on the rotating earth, we find that by directly dealing with

viscous boundary-layer (i.e. Ekman’s) flows, one can quickly grasp why

most of the ocean’s interior is nearly inviscid yet why the boundary layers

are so important for the interior flows.

POM and related files for exercises outlined in this book can be downloaded

from:

ftp://aden.princeton.edu/pub/lyo/pom_gfdex/

Download latest public-released POM from:

http://www.aos.princeton.edu/WWWPUBLIC/PROFS/waddow

nload.html

Download POM User Guide other releases from:

http://www.aos.princeton.edu/WWWPUBLIC/htdocs.pom/

Page 5

CHAPTER 1: Wind-Driven Ocean Currents

The book begins with the near-surface ocean response to wind.

We

will for the moment assume that the ocean density ( 1035 kg m-3) is

constant. Throughout this book, unless explicitly stated, we will use the SI

units. Most of us experience the ocean perhaps through a summer swim in

a coastal sea or in a lake. Wind-driven surface motions in the form of

waves and surfs are familiar. However, these motions can involve large

vertical accelerations and are of very small scales (order of centimeters to

meters, O(cm-m)) which we will not model for now, at least not directly.

Instead, we focus on motions which are of sufficiently large scales in the

horizontal (scale L ~ O(1-1000 km)) compared to vertical (scale D ~ O(101000 m)), D/L << 1, that the pressure field satisfies the hydrostatic equation:

𝜕𝑝

𝜕𝑧

= −𝜌𝑔,

(1-1)

where a Cartesian coordinate system xyz is used such that, conventionally, x

and y are the west-east and south-north axes respectively, and z is the

vertical axis with z = 0 placed at the mean sea level (MSL; Figure 1-1); x, y

and z are measured in m. The pressure p is in N m-2 (also called Pascal,

Pa), and g ( 9.806 m s-2) is the acceleration due to gravity.

In other

words, the motions of interest occur in such thin fluid layers (with D/L <<

1) that as far as the vertical force balance is concerned the fluid may be

treated as being static.1 For such an atmosphere-ocean system, the pressure

at some depth z = z’ in the water is just the weight per unit area of fluid

(water and air) above, or

p = [mass per area].g = [ (-z’) + <eazea> ].g

(1-2)

1 The thinness of the oceanic (or atmospheric) layer relative to its horizontal extent is

comparable to that of the thickness of paper of this book relative to its width.

Page 6

Figure 1-1. A sketch of water of mean depth H(x,y) and free surface (x,y,t).

Here, z = (x,y,t) is the free surface; and/or z’ can be positive or negative,

and z’ ( 0) represents the distance from the sea-surface to the point z = z’

in the water.

The term <eazea> represents the mass per area of the

atmosphere, it is given by

∞

∞

<eazea> = ∫ 𝑎 𝑑𝑧 ∫0 𝑎 𝑑𝑧

(1-3)

where a is the air density. Thus ea and zea may be thought of as the

effective density and height of the “air-containing” atmosphere. The main

bulk (about 80%) of the atmosphere’s mass is within the lowest layer (the

troposphere) of about 10 km thick such that the atmospheric pressure at the

sea surface, pa = <eazea>.g 105 N m-2 = 1 bar.2 Equation (1-2) can be

written as

2 An easy way to remember this is to use ea 1 kg m-3, zea 10 km and g 10 m s-2. Note

also the familiar weather reporting of “1000 millibar” etc, which is 1 bar, the approximate sealevel pressure.

Page 7

p = g(-z’) + pa(x,y,t)

(1-4)

which is also obtained by integrating (1-1) from z = z’ to z = ; in general,

the pa is a function of the horizontal position and time.

If both a and pa do not vary with (x, y) and either are steady or at

most only vary so slowly with time that the fluid remains in hydrostatic

equilibrium, i.e. (1-1) is satisfied, then the fluid remains motionless provided

that initially it is also at rest. A simple system to imagine is water in an

annulus channel (Figure 1-2). If the axis of the annulus is far from the

center, so that r/Ranu << 1, where r is the width of the channel, and Ranu is the

radius of curvature of the annulus, then one can approximate the

(motionless) water to be in a straight channel with x directed along the

channel axis, y across the channel (Figure 1-2) and a vertical slice along the

axis gives Figure 1-1. Modelers refer to this kind of channel a “periodic

channel” since, starting from a yz-section at any x-location and going around

along the axis, the field variables return to the same values. When

conducting geophysical fluid experiments, a periodic channel is a convenient

configuration to use because it often allows the extraction of essential flow

physics while at the same time alleviates the modeler from having to

formulate more complicated boundary conditions.

Page 8

Figure 1-2. A circular annulus channel of radius Ranu much larger than the

width of the annulus r. This is used to illustrate along-channel periodic

fluid motion within the annulus.

1-1: A Simple Shearing Flow by the Wind

Consider therefore the straight channel (Figure 1-1) in which we will

further assume that all variables are independent of the cross-channel axis

“y,” and that the earth’s rotation is nil. The flow is described by the three

components of velocity (u, v, w) and the pressure p. Since there can be no

flow across the channel wall, i.e.

v = 0,

at y = 0 and y = r,

t.

(1-5)

the cross-channel velocity v must be zero everywhere; the symbol t means

“at all time.”

The channel is further idealized by letting its depth H =

constant. Initially, at t = 0, the water is at rest. A wind stress (N m-2) is

then applied uniformly at the surface, so that is a function of time only:

= (t)

(1-6)

Similarly, we could stipulate that pa is also a function of time only; but for

simplicity we will set

pa = 0.

(1-7)

It follows that, the along-channel velocity u cannot vary with x. Therefore,

at any point, there can be no accumulation (convergence or divergence) of

mass, and since w = 0 at z = H, the vertical velocity is nil everywhere, and

the sea-surface remains flat. Thus,

u = u(z, t),

w = 0 = /x = p/x.

(1-8)

Under these very specialized conditions, a parcel of fluid experiences

acceleration only due to the vertical shear stress. The momentum balance

is then:

𝐷𝑢

𝐷𝑡 =

𝜕𝑧𝑥

𝜕𝑧

(1-9)

Page 9

where zx denotes shear stress (force per unit area) in the x-direction acting

on the fluid elemental face that is perpendicular to the z-axis, and D(.)/Dt is

the material derivative which for a fluid property S is given by

𝐷𝑆

𝐷𝑡

=

𝜕𝑆

𝜕𝑡

+𝑢

𝜕𝑆

𝜕𝑥

+𝑣

𝜕𝑆

𝜕𝑦

+𝑤

𝜕𝑆

𝜕𝑧

.

(1-10)

For the present specialized case, the last three terms are nil, and with S = u,

we have

𝐷𝑢

𝐷𝑡

=

𝜕𝑢

𝜕𝑡

. A loose analogy is a stack of poker cards which are

glued with a special adhesive that is never dry and thus remains sticky.

The top card is then “pulled” parallel to the card’s surface a small distance

and it drags upon the card below it. In our fluid system, the wind is doing

the “pulling” by transferring air momentum onto the water’s surface (and we

assume that no ripples or wind waves are produced!). Momentum is

vertically transferred from the surface to fluid layers below – upper fluid

drags upon the lower fluid which in turn drags upon the layer further below,

and so on (Figure 1-3).

Figure 1-3. The ocean is treated as a (vertical) stack of thin layers each of

thickness z : shown are layers “1” and “2;” layer “0” is air. The Fmn is

(shearing) force per unit (horizontal) area due to layer “m” on layer “n.”

The formulae show that the net force per unit area in layer “1” is F1net = F01

+ F21 =z.zx/z. Therefore, the net shearing force per unit mass is F1net x

Page 10

y/(xyz) = (zx/z)/. This, in the idealized case described in the text,

is = u/t, the acceleration in the x-direction.

For the so called Newtonian fluid such as water, the shear stress zx is

proportional to the vertical rate of change of fluid velocity (i.e. the vertical

“rate of strain”):

zx =

𝜕𝑢

𝜕𝑧

(1-11)

where is the viscosity which to a good approximation may be taken as a

constant and moreover is rather small; it is 10-3 kg m-1 for water and

1.7×10-5 kg m-1 for air. Equation (1-11) is valid for laminar or slowlymoving viscous flows void of turbulent movements we usually see in say, a

mountain stream or in swirling air vortices around a house. However, as

will be seen below, one often model oceanic and atmospheric flows using a

similar formula, except that an “eddy viscosity” e is used to represent the

aggregated effects of small eddies on the large-scale flows. The eddy

viscosity is much larger than the molecular viscosity and is moreover not a

constant – it depends on the flow.

The “e” will be ascribed below but for

now we will proceed with our model formulation using equation (1-11).

Equation (1-9) then becomes:

𝜕𝑢

𝜕𝑡

=

𝜕

𝜕𝑧

(𝑒

𝜕𝑢

𝜕𝑧

(1-12)

)

where e = e/, the kinematic eddy viscosity. This is a simple “heatdiffusion” equation that can be easily solved subject to some initial

conditions and boundary conditions at z = 0 and z =H; for example:

u = 0,

t=0

(1-13)

u = 0,

z = H

(1-14a)

Page 11

𝜕𝑢

𝑒 𝜕𝑧 =

𝑜

,

z = 0,

(1-14b)

where o is a constant wind stress.

Exercise 1-1A: Use POM to solve (1-12) subject to (1-13) and (1-14) in a

periodic straight channel. Compare your solution with exact (analytical)

solution. Experiment with different grid sizes as well as with more

complicated initial and/or boundary conditions. Analyze and discuss your

results (e.g. use Matlab or IDL etc).

Exercise 1-1B: Repeat Exercise 1-1A using a e-profile that decays with

depth, e.g. e = eo exp(z), where eo and are constants.

Exercise 1-1C: Repeat Exercise 1-1A using an annulus channel (Figure 12) instead of the straight (periodic) channel. Use a curvilinear grid (in

POM) for this exercise. Experiment with various values of Ranu and r.

Compare and discuss your results. Are the results substantially different

from the straight-channel case when Ranu is “not too large” (define what this

means), why? Is equation (1-12) still valid then? Why (or why not)?

1-2: Effects of Earth’s Rotation

In the above straight-channel flow example, we saw that the crosschannel flow is nil. This is no longer true if the channel is placed on a

turntable and rotates about a vertical axis. We now expand the study of

wind-driven shearing flow to the case when the earth’s rotation cannot be

ignored. We can imagine that the earth is the “turntable.” If our channel

is placed at the (celestial) pole, then it rotates about the earth’s rotation axis

once every day (0.997258 day to be more exact) anticlockwise at the north

pole and clockwise at the south pole (Figure 1-4). Thus the rotational

frequency = 2/(86163.09 s) = 7.292 10-5 s-1. If the channel is placed

on the (celestial) equator, then there is no rotation (though the channel is

being carried west to east at a great speed = Rearth 1673 km/hour; Rearth

6371 km is the radius of a sphere having the same volume as the earth).

a given latitude, the rotational frequency is:

Rot() = .sin(), /2 +/2

At

(1-15)

Page 12

with the convention that positive (negative) is anticlockwise (clockwise).

Figure 1-4.

The Earth's axial tilt (or obliquity) and its relation to the

rotation axis and plane of orbit (from Wikipedia).

We are anchored (by gravity) to the earth and therefore also rotate as

the channel does. It is most convenient to describe phenomenon referenced

to this rotating coordinate frame rather than to a fixed, inertial frame. For

scalar quantities such as the temperature or salinity of a (generally moving)

fluid parcel, a change in the frame of reference clearly will not change their

value. The parcel’s momentum is a different story. While the phenomena

are still independent of the frame of reference, our perception of the

phenomena as well as their descriptions are altered. An example is offered

in Figure 1-5.

Page 13

Figure 1-5.

A turntable rotating at a constant radians/s with two

observers “A” and “B” on it. At time t o “A” throws the ball (red) to “B.”

A time-interval “t” later, the relative position of both observers are

unchanged (and neither perceive any change). Let the ball’s speed be such

that it arrives at the original B’s position in the same time-interval. To

“A,” the ball has been forced to the right of “B.” This apparent force is

called the Coriolis force. It is only perceived by “A” (and “B”) in the

rotating frame but not felt by an outside observer in an inertial frame.

We now derive the momentum equation on a rotating frame. We

examine first the rate of change of an arbitrary vector (e.g. the momentum)

B = B1i1 + B2i2 + B3i3 in a rotating Cartesian frame of reference with unit

vectors (along x, y and z) i1, i2 and i3 [Pedlosky, 1979]. By chain rule:

𝑑𝑩

( ) =

𝑑𝐵𝑘

𝑑𝑡 𝐼

𝑑𝑡

𝑑𝑩

𝑑𝐵𝑘

𝐢𝑘 +

𝑑𝐢𝑘

𝑑𝑡

(1-16)

𝐵𝑘 ,

where repeated index k means summation over all k = 1, 2 and 3, and the

subscript I denotes rates of change as seen from an observer in the inertial

frame, respectively.

Clearly, the first term on the RHS of (1-16) is

( ) =

𝑑𝑡 𝑅

𝑑𝑡

(1-17)

𝐢𝑘

i.e. it is the rate of change of Bk when ik is fixed, i.e. when the observer is

himself rotating, hence is not able to sense the rotation of the coordinate

axes. The second term on the RHS of (1-16) involves

𝑑𝐢𝑘

𝑑𝑡

, the rate of

change of a vector of fixed length (i.e. a unit vector), hence its change is

completely due to its changing direction as the coordinate axes rotate.

From Figure 1-6, we see that

𝑑𝑨

( ) = × 𝑨

𝑑𝑡

where

(1-18)

is the angular velocity at which the constant-length vector A

rotates. Setting A = ik and using (1-17) and (1-18), equation (1-16) gives

𝑑𝑩

𝑑𝑩

𝑑𝑡 𝐼

𝑑𝑡 𝑅

( ) = ( ) + × 𝑩

(1-19)

Page 14

Figure 1-6. Rate of change of a vector A of fixed length caused by it being

rotated by . This rate of change is seen from the sketch to be a vector of

length |||A|sin(), where is the angle between A and , directed

perpendicular to the plane formed by A and , i.e. it is simply the vector

product A.

Thus the rate of change of the vector B in the inertial (non-rotating) system

𝑑𝑩

consists of two parts. The first part, ( ) , is the rate of change as seen by

𝑑𝑡

𝑅

an observer (that is us) “glued” to the rotating frame of reference (that is the

earth). To this must be added the second part, B, in order that the

𝑑𝑩

correct rate of change, ( ) , can be used in Newton’s law to describe fluid

𝑑𝑡

𝐼

𝑑

motion. This equates the rate of change ( ) of momentum following a

𝑑𝑡

fluid element in an inertial frame of reference to the sum of forces acting on

the element:

Page 15

𝑑𝒖

( 𝑑𝑡𝐼) = −𝑝 + + 𝐹 (𝒖𝐼 ),

(1-20)

𝐼

where the subscript I again reminds us that the equation is valid only in an

inertial frame of reference. The RHS is the sum of the pressure gradient

force p, the body force , and the viscous force F(uI) which for

Newtonian fluids with molecular viscosity is

𝐹 (𝒖𝐼 ) = (𝒖𝐼 ) + (𝒖𝐼 ).

(1-21)

3

These equations are derived, for example, in Batchelor [1967]. Applying

(1-19) to the position vector r of the fluid element, and also to uI (i.e. setting

B = r and B = uI in turn), we obtain,

𝒖𝐼 = 𝒖𝑅 + × 𝒓

𝑑𝒖𝐼

(

𝑑𝑡

) =(

𝐼

𝑑𝒖𝐼

𝑑𝑡

(1-22a)

) + × 𝒖𝐼

(1-22b)

𝑅

𝑑𝒓

𝑑𝒓

where in (1-22a) we have set ( ) = 𝒖𝐼 and ( ) = 𝒖𝑅 . As seen in the

𝑑𝑡

𝑑𝑡

𝐼

𝑅

inertial frame (from a “fixed star” outside the planet earth), the fluid velocity

uI consists of the velocity uR measured by an earth-bound observer, plus an

amount equal to the rate r (in m/s) at which the fluid element is being

carried along by the rotating earth. Since uR is the velocity we directly

observe, we substitute (1-22a) into (1-22b), (1-21) and (1-20) to express the

equation of motion entirely in term of uR. Thus, (1-22b) becomes:

𝑑𝒖𝐼

(

𝑑𝑡

) =(

𝐼

𝑑𝒖𝑅

𝑑𝑡

) + × 𝒖𝑅 + × ( × 𝒓),

𝑅

where we have assumed that

𝑑

𝑑𝑡

is small compared to other terms.

(1-22b)

Figure

1-7 explains that (r) is a centrifugal acceleration that can be expressed

as the gradient of a centrifugal potential c; it therefore can be grouped

with the body force on the RHS of (1-20), i.e. (+c) = g, the acceleration

due to gravity. The direction of g is conveniently taken to align with the z-

Page 16

axis, positive upwards. Since |(r)| < ||2 Rearth 3.410-2 m s-2, the

centrifugal acceleration makes but a small correction to the radial direction

that is “vertical” were the earth not rotating.

Note that (r) is zero at

the poles and is maximum at the equator; it accounts for the slight bulge of

the earth around the equator. Substituting (1-22a) into (1-21), one can

show that F(uI) = F(uR). Thus substituting (1-22b) into (1-20) gives:

𝑑𝒖

( 𝑑𝑡𝑅 ) = − × 𝒖𝑅 − 𝑝 − 𝒈 + 𝐹 (𝒖𝑅 ),

𝑅

(1-23)

which is entirely in terms of quantities in the rotating frame of reference.

As written, equation (1-23) is valid also for non-constant . Henceforth the

subscript R will be dropped.

Figure 1-7.

(a) Sketch showing the centrifugal acceleration vector

(r) = ||2|r|sin()nc

of a fluid material volume element with

Page 17

position r on the earth’s surface (at latitude = /2 - ), directed along the unit

vector nc perpendicular to and away from the axis of rotation of angular

momentum . For convenience, the origin of r is at the earth center, but

this is irrelevant. (b) Sketch showing the vector sum (+c), of (i) ,

the gravitational acceleration vector directed towards the center of the earth,

where is the gravitational potential, and (ii) c =(r) =||2r [see

sketch (a) for meaning of r], where c is the centrifugal potential. Let r =

xk ik , then c = (||2x2k )/2 as direct differentiation using = ik (/xk)

shows. Note also that c = (||2|r|2)/2 = |r|2/2. In geophysics, the

summed vector (+c) = g is called the acceleration due to gravity and

the direction of g (i.e. “upwards”) is conveniently aligned with the z-axis.

The Equation of Motion Applied to Large-Scale Oceanic Flows:

Written in component form, (1-23) is:

𝐷𝑢

𝜕𝑝

𝐷𝑣

𝜕𝑝

( 𝐷𝑡 ) = − (⏟

2 𝑤 − 3 𝑣) −

+ (𝑢)

𝜕𝑥

(1-24a)

( 𝐷𝑡 ) = − (3 𝑢 − ⏟

1 𝑤 ) −

+ (𝑣)

𝜕𝑦

(1-24b)

𝐷𝑤

𝜕𝑝

−(1 𝑣 − 2 𝑢) − 𝑔 − 𝜕𝑧 + ⏟

(𝑤)

⏟( 𝐷𝑡 ) = ⏟

(1-24c)

In arriving at these equations, we have used the incompressibility condition

𝒖 = 0

(1-25)

to eliminate the second term on the RHS of (1-21). Equation (1-25) is also

often called the continuity equation, a term that we will also use, though this

is correct only if effects of density change on mass balance are negligible.

𝑑

𝐷

Instead of ( ), we have also used the more conventional notation ( ) to

𝑑𝑡

𝐷𝑡

denote the substantive derivative:

Page 18

𝐷𝐺

(

𝐷𝑡

)=

𝜕𝐺

𝜕𝑡

+ 𝒖𝐺

(1-26)

i.e. the rate of change of a field variable G following the fluid’s material

volume element. This is permitted since the vector r (Fig.1-7) denotes the

position of the fluid element. A localized coordinate has been chosen such

that the direction of 23 points in the z-direction and its magnitude is (c.f.

Figure 1-7) 2sin() = f, say, where is the latitude of the fluid element.

The “f” is called the Coriolis parameter; it is zero at the equator, and is a

maximum (=2) at the pole as noted previously when discussing equation

(1-15). For large-scale, thin-fluid flows (i.e. D/L << 1) that we will mostly

focus on, it can be shown [e.g. Pedlosky, 1979; Gill, 1982] through a scaling

analysis that the ⏟

( … ) terms in (1-24) are generally quite small compared

to other terms in the same equation; these terms will therefore be dropped.

The molecular viscous terms (u) are also very, very small; though their

importance increases as the scale of motion becomes very small and

eventually they provide the necessary energy dissipation for the fluid

system. In models, effects of turbulence are usually parameterized by

invoking an eddy or effective viscosity which in the vertical (z) is denoted by

M (or diffusivity KH for heat and salt, chapter 3; two excellent texts are

Hinze, 1961, and Schlichting, 1963); these have much enhanced values than

their molecular counterparts: KM >> , a result of “eddy mixing” on the

small scales.3 Unlike the molecular viscosity, the eddy viscosity depends

on the flow itself, hence is a function of time and space, and in general takes

different forms in the vertical and horizontal directions (i.e. non-isotropic).

Various models of turbulence are available for KM (and KH). For example,

the Mellor and Yamada’s [1982] parameterization scheme is very popular

and is used in many oceanic and atmospheric circulation models including

3 A proper treatment involves Reynolds averaging – see Hinze, 1961. Equation (1-24)

is then called the Reynolds equation.

Page 19

the Princeton Ocean Model. While parameterizations for the vertical eddy

viscosity and diffusivity are relatively well-known, those for enhanced

horizontal eddy viscosity and diffusivity are in comparison still a subject of

much debate. Unless otherwise stated, we will assume that horizontal

viscosity and diffusivity are small, and include them only for the purpose of

numerical computations: stabilization of the numerical schemes and/or

elimination of grid-point (“2x” oscillatory) noise [e.g. Roach, 1972].

Excellent reviews of turbulence mixing in geophysical flows can be found in

the various chapters of the book edited by Baumert et al. [2005].

With the above simplifications, equation (1-24c) becomes

𝜕𝑝

𝜕𝑧

= −𝑔

(1-27)

which is the hydrostatic equation (1-1) except that it is seen to be valid also

for non-uniform .

Indeed, (1-24) admits a “static” solution

u = 0, = o(z) and p = po(z)

(1-28)

which however is not very interesting. More interesting flows are

produced as a result of deviations of the pressure field from this hydrostatic

state:

= o(z) + ’,

p = po(z) + p’

(1-29)

where the ’ and p’ are perturbation density and pressure respectively. In

the ocean o oc = 1025 kg m-3 say, where oc is a constant density, and

’ is generally a small fraction of this: ’/o 0.01 and smaller.

Subtracting (1-28) from (1-24), letting o in the acceleration terms, and

dividing through by o, we obtain:

𝐷𝑢

1 𝜕𝑝′

𝐷𝑡

𝐷𝑣

𝑜 𝜕𝑥

𝐷𝑡

𝑜 𝜕𝑦

( ) = +𝑓𝑣 −

( ) = −𝑓𝑢 −

1 𝜕𝑝′

+

+

𝜕

𝜕𝑧

𝜕

𝜕𝑧

(𝐾𝑀

(𝐾𝑀

𝜕𝑢

)

(1-30a)

)

(1-30b)

𝜕𝑧

𝜕𝑣

𝜕𝑧

Page 20

𝜕𝑝′

𝜕𝑧

= −′𝑔

(1-30c)

with an error in (1-30a,b) that is at most O(’/o).

1-3: Wind-Driven Homogeneous Flows with Rotation

Equations (1-25) and (1-30) are insufficient to solve for u, v, w, ’ and

p’. Additional equations involving the heat and salt equations as well as

the equation of state are required. These will be discussed in chapter 3.

Here, we study the case of a homogeneous fluid of constant density (i.e. ’

is known, ’ = 0), for which equations (1-25) and (1-30) are then complete

and may be solved for u, v, w, and p’, given appropriate initial and boundary

conditions.

For this homogeneous fluid system, while ’ = 0, p’ is not and it may

be written in terms of the free surface . Assume then a free-surface z =

(x, t) in an idealized ocean of depth z = H but with no lateral boundaries.

There can be no flow across the surface and bottom, i.e. z = and z = H are

material surfaces, and D(z)/Dt and D(z+H)/Dt are both = 0:

𝑤=

𝜕

𝜕𝑡

+𝑢

𝑤 = −𝑢

𝜕𝐻

𝜕𝑥

𝜕

𝜕𝑥

+𝑣

−𝑣

𝜕𝐻

𝜕𝑦

𝜕

𝜕𝑦

,

, 𝑎𝑡 𝑧 = (𝑥, 𝑦, 𝑡),

(1-31a)

𝑎𝑡 𝑧 = −𝐻 (𝑥, 𝑦).

(1-31b)

These equations constitute the upper and lower boundary conditions for our

problem. From (1-30c) with ’ = 0, we have p’ = p’(x, y, t); also the first of

(1-29) gives = o, a constant. Integrating (1-27) and using the second of

(1-29) yield:

p = ogz + function(x, y, t) = po(z) + p’(x, y, t),

(1-32a)

Page 21

from which we may let

po = ogz

(1-32b)

Across the air-sea interface, z = , the total pressure p must be continuous

and equal to pa, so that (1-32) gives:

p’ = og + pa.

(1-33)

The incompressibility condition (1-25) can now be used to relate (or p’) to

the velocity. Integrating (1-25) from z = H to z = and applying (1-31):

𝜕

𝜕𝑡

=−

𝜕𝑈

𝜕𝑥

−

𝜕𝑉

(1-34a)

𝜕𝑦

(𝑈, 𝑉) = ∫−𝐻(𝑢, 𝑣)𝑑𝑧

(1-34b)

Equation (1-34) can also be re-written in term of a vertically-averaged

𝜕

velocity (𝑢

̅, 𝑣̅ ) = ∫−𝐻(𝑢, 𝑣)𝑑𝑧/𝐷 , where 𝐷 = 𝐻 + , so that

=

𝜕𝑡

−

̅

𝜕𝐷𝑢

𝜕𝑥

−

𝜕𝐷𝑣̅

𝜕𝑦

. The form used in (1-34) shows explicitly however that the

equation is valid for general (u, v) that may also be a function of z (as well as

of x, y and t).

Substituting (1-33) into (1-30a,b), the resulting equations and (1-34)

are grouped together here for convenience:

𝜕

=−

𝜕𝑡

𝐷𝑢

𝜕𝑈

𝜕𝑥

−

𝜕𝑉

(1-35a)

𝜕𝑦

( ) = +𝑓𝑣 − 𝑔

𝜕

𝐷𝑡

𝐷𝑣

𝜕𝑥

𝜕

𝐷𝑡

𝜕𝑦

( ) = −𝑓𝑢 − 𝑔

+

+

𝜕

𝜕𝑧

𝜕

𝜕𝑧

(𝐾𝑀

(𝐾𝑀

𝜕𝑢

𝜕𝑧

𝜕𝑣

𝜕𝑧

)

(1-35b)

).

(1-35c)

These constitute three equations to be solved for (u, v, ) given appropriate

initial and boundary conditions. These are in fact the equations solved

numerically in POM. After (u, v) are solved, the incompressibility

condition (1-25) is then used to solve for w. Before we describe the

numerical solution however, it is instructive to examine more closely how

one can approach the problem analytically.

Page 22

1.3.1 Boundary-Layer and Interior Flows:

For analytic treatment, we closely follow Pedlosky [1979]. We

study a problem in which the ocean is confined in the vertical by a free

surface z = (x,y,t) and a bottom z = H(x,y), but is unbounded in the

horizontal. It is more direct to use (1-25) and (1-30), which are repeated

here:

𝜕u

𝜕v

+ 𝜕𝑦 +

𝜕𝑥

⏟

𝜕𝑡

⏟

+𝑢

𝜕u

𝜕𝑥

+𝑣

𝜕u

𝜕𝑡

⏟

+𝑢

𝜕v

𝜕𝑥

𝜕𝑝′

𝜕𝑧

= +𝑓𝑣

⏟ −

(3) 𝑓𝑜 𝑈

(2) 𝑊𝑈/𝐷

+𝑣

(1) 𝑈 2 /𝐿

𝜕u

+ 𝑤

⏟

𝜕𝑦

𝜕𝑧

(1) 𝑈 2 /𝐿

𝜕v

(1-36a)

=0

(2) 𝑊/𝐷

(1) 𝑈/𝐿

𝜕u

𝜕w

⏟

𝜕𝑧

𝜕v

𝜕𝑦

𝜕v

+ 𝑤

⏟

𝜕𝑧

= − 𝑓𝑢

⏟ −

(2) 𝑊𝑈/𝐷

(3) 𝑓𝑜 𝑈

1 𝜕𝑝′

⏟

𝑜 𝜕𝑥

𝜕

+ ⏟ (𝐾𝑀

1 𝜕𝑝′

) (1-36b)

𝜕𝑧

𝜕𝑧

(5) 𝐾𝑈/𝐷2

(4) 𝑃/𝑜 𝐿

⏟

𝑜 𝜕𝑦

𝜕𝑢

𝜕

+ ⏟ (𝐾𝑀

(4) 𝑃/𝑜 𝐿

𝜕𝑣

) (1-36c)

𝜕𝑧

𝜕𝑧

(5) 𝐾𝑈/𝐷2

(1-36d)

=0

Under each term, we indicate its order of magnitude by using the following

scale for each variable:

(x,y) L;

t L/U;

z D;

(u,v) U;

w W ~ UD/L;

p’ P ~ oLfoU; f fo

where “” means “have/has the scale of.”

KM K;

(1-37a)

(1-37b)

(1-37c)

Expression (1-37a) sets the

basic scales for the horizontal (L) and vertical (D) distances, and also the

horizontal velocity (U) and the eddy viscosity (K). The time scale (L/U) in

(1-37b) is chosen to be the “advective time scale,” i.e. the time taken for a

parcel of fluid to cover a distance of about L. If f is constant, then:

f/fo = ±1

(1-37d)

where the plus (minus) sign is for the northern (southern) hemisphere. The

vertical velocity scale W is chosen as follows. In order to satisfy the

continuity equation (1-36a), horizontal divergences or convergences

Page 23

𝜕𝑢

𝜕𝑣

(𝜕𝑥 + 𝜕𝑦) must be balanced by vertical motion

𝜕𝑤

𝜕𝑧

such that their net sum

is zero; thus we set terms (1) and (2) in (1-36a) to be of the same order, and

W ~ UD/L. It follows then that the scale of term (2) of equations (1-36b,c),

WU/D ~ U2/L, which is also the scale of term (1) of these equations;

although |w| is in general much smaller than |u| or |v|, it multiplies the

𝜕𝑢

vertical gradient

𝜕𝑧

or

𝜕𝑣

𝜕𝑧

which is generally much larger than the

horizontal velocity gradients such as 𝑢

𝜕𝑢

𝜕𝑥

. The scale for pressure in (1-

37c), P, is such that the horizontal pressure gradients balance the Coriolis

acceleration (see below). It is easy to see now that when the variables in

(1-36) are non-dimensionalized by the above scales, the equations become

[after dividing (1-36b,c) through by the scale (foU)]:

𝜕u

+

𝜕𝑥

𝜕v

𝜕𝑦

𝜕u

+

𝜕w

𝜕𝑧

𝜕u

(1-38a)

=0

𝜕u

𝜕u

1 𝜕𝑝′

( 𝜕𝑡 + 𝑢 𝜕𝑥 + 𝑣 𝜕𝑦 + 𝑤 𝜕𝑧 ) = 𝑓𝑣 −

𝑜

𝜕v

𝜕v

𝜕v

𝜕v

𝜕𝑥

1 𝜕𝑝′

(𝜕𝑡 + 𝑢 𝜕𝑥 + 𝑣 𝜕𝑦 + 𝑤 𝜕𝑧 ) = −𝑓𝑢 −

𝑜

𝜕𝑝′

𝜕𝑧

+

𝜕𝑦

𝐸𝑣 𝜕

2 𝜕𝑧

+

(𝐾𝑀

𝐸𝑣 𝜕

2 𝜕𝑧

𝜕𝑢

)

(1-38b)

𝜕𝑣

) (1-38c)

𝜕𝑧

(𝐾𝑀

𝜕𝑧

(1-38d)

=0

where now all variables are dimensionless, f = ±1 for constant Coriolis and

𝑈

2𝐾

𝑜

𝑜

= 𝑓 𝐿 = 𝑅𝑜𝑠𝑠𝑏𝑦 𝑛𝑢𝑚𝑏𝑒𝑟, 𝐸𝑣 = 𝑓 𝐷2 = 𝐸𝑘𝑚𝑎𝑛 𝑛𝑢𝑚𝑏𝑒𝑟 (1-39)

are the two parameters of the problem (the factor “2” in Ev is for

convenience, below).

The non-dimensionalized kinematic boundary

conditions at z = and z = H have the same form as equations (1-31a,b).

Equations (1-38b,c) show that the Coriolis and pressure gradient

terms are of the same order, both of these terms in (1-38b,c) are multiplied

by “1.” Thus by choosing the scales as those in (1-37c), we implicitly

assume that the Coriolis acceleration terms are important, and are in fact of

the same order of magnitude as the pressure-gradient terms. Clearly this

choice is only valid if “f” is not zero; the scaling (and balance of terms) will

need to be changed close to the equator. Observations of most oceanic

(and atmospheric) flows do indicate that away from the equator, pressure

gradients approximately balance Coriolis accelerations. From (1-38b,c) we

Page 24

see that the conditions for this to be true are that the Rossby and Ekman

numbers are small. The former requires that either the flow is not strong

and/or the horizontal scale L is sufficiently large – for example, U 0.1 m/s,

L > 10 km for fo 10-4 s-1. The latter requires that the Ekman scale

(2K/fo)1/2 is much smaller than the ocean depth D; if K 10-4~10-1 m2 s-1, this

requires that D > 10~50 m.

However, close to a boundary, no matter how small the eddy viscosity

KM is, at some point the shear terms

𝐸𝑣 𝜕

2 𝜕𝑧

(𝐾𝑀

𝜕(𝑢,𝑣)

𝜕𝑧

) become important.

This is most apparent at the bottom boundary where the fluid parcel cannot

have a relative motion with respect to that boundary, i.e. the “no-slip”

condition must be satisfied:

ntu = 0, or approximately u = 0,

at z = H(x,y)

(1-40)

where nt is the unit vector tangential to the bottom. Therefore, unless the

flow is trivially zero, the interior (i.e. away from the bottom) velocity of a

real-fluid (i.e. fluid with viscosity) flow must decrease in value until it

becomes zero at the bottom.4 Since Ev is small, the only way the viscous

terms

𝐸𝑣 𝜕

2 𝜕𝑧

(𝐾𝑀

𝜕(𝑢,𝑣)

𝜕𝑧

) can become large enough to balance the Coriolis

acceleration term is if the z-derivatives of (u, v) become very large, i.e. if the

decrease of velocity from the interior to the bottom occurs within a thin

layer in the immediate neighborhood of the bottom. This thin layer is

called a boundary layer, or a bottom boundary layer in the present case. A

similar thin layer also exists near the surface where wind stresses are

applied.

Geostrophic Nearly-Inviscid Interior Flows:

Far away from boundaries, then, one expects that the flow is nearly

inviscid and one may approximate equation (1-38b,c) by dropping the term

4 An inviscid flow needs only to satisfy the no-normal flow condition

equation (1-31b), so that a fluid parcel can ‘slip’ past the bottom.

Page 25

involving Ev. Just exactly how far is “far” will be determined below. If

is also small, equations (1-38b,c) then give (for f = ±1):

𝑣𝑔 =

1 𝜕𝑝′

(1-41a)

𝑜 𝜕𝑥

1 𝜕𝑝′

𝑢𝑔 =

(1-41b)

𝑜 𝜕𝑦

Oceanographers call the horizontal velocity (ug, vg) that satisfy (1-41)

geostrophic velocity, and the equation geostrophic relation. In the northern

hemisphere, a higher pressure in the south (east) than in the north (west),

p’/y < 0 (p’/x > 0) would produce an eastward (northward) geostrophic

velocity ug > 0 (vg > 0). The geostrophic flow around a center of high

(low) pressure is therefore clockwise (anticlockwise) or anticyclonic

(cyclonic). The direction of the flow is reversed in the southern

hemisphere (f < 0). For homogeneous fluid flow, since p’ is independent of

z (see 1-38d), (ug, vg) is therefore also independent of z. From (1-41), a

geostrophic flow also has zero horizontal divergence:

𝜕𝑢𝑔

𝜕𝑥

+

𝜕𝑣𝑔

𝜕𝑦

(1-42)

= 0,

so that the corresponding vertical velocity wg satisfies:

𝜕𝑤𝑔

𝜕𝑧

(1-43)

=0

All three components of the geostrophic velocity (ug, vg, wg) are therefore

independent of z, the rotation axis. This is the Taylor-Proudman theorem

which is valid for inviscid homogeneous slow (small ) flow. If the upper

or lower boundary is flat, so that wg = 0 there, then wg = 0 through the water

column. The motion is then two dimensional, (ug, vg) 0, but wg = 0.

Figure 1-8 shows an example of this type of flow.

(See Exercises).

Strictly speaking, the model solution in Fig.1-8 is still evolving in time, so it

is not steady and does not exactly satisfy equations (1-41), (1-42) and (1-43).

This is an important point – purely geostrophic flows satisfying exactly (141) through (1-43) are indeterminate. Any p’(x,y) satisfies the hydrostatic

relation (1-38d), and (ug, vg) can be constructed to satisfy the two

(approximate) momentum equations (1-41a,b); the unknown (ug, vg) in turn

Page 26

is horizontally non-divergent (equation 1-42) which simply requires that the

vertical velocity wg is independent of z. We know all these information

(hence the Taylor-Proudman theorem) but cannot pin down what the flow is!

To arrive at the unique model solution shown in Fig.1-8, we actually

included the small terms on the left hand side of momentum equations (138b,c), the time-dependent terms in particular.5 Another way to pin down

a unique solution is to include the shear terms

𝐸𝑣 𝜕

2 𝜕𝑧

(𝐾𝑀

𝜕(𝑢,𝑣)

𝜕𝑧

) which of

course have the added benefit that we can then also satisfy the physically

relevant no-slip bottom condition (1-40) and the conditions at the sea surface

where windstress may be applied.

5 There were additionally horizontal viscous terms on the RHS of (1-38b,c) included for

numerical stability, but these were small and unimportant to the arguments presented

here.

Page 27

Figure 1-8. Nearly-steady homogeneous (constant-density) flow in an xperiodic channel, 600km by 300km, of depth 200m except at the channel’s

center where a cylinder rises 50m above the bottom. Color is sea-surface

height in meters and vectors are velocity at (A) z=0m (i.e. surface), (B)

z=90m and (C) z=180m. This model calculation was carried out for 100

days when the flow has reached a nearly steady state. The experiment is

meant to illustrate Taylor-Proudman theorem: flow below the cylinder’s

height goes around the cylinder while above it the flow also tends to go

around as if the cylinder extends to the surface. The velocity does not vary

with “z” and the vertical velocity (which is not shown) is nearly zero.

Viscous Boundary-Layer Flows:

Page 28

It was mentioned before that no matter how small the Ekman number

Ev is, at some point close to the boundary the shear terms

𝐸𝑣 𝜕

2 𝜕𝑧

(𝐾𝑀

𝜕(𝑢,𝑣)

𝜕𝑧

)

become large enough that they balance the Coriolis and pressure gradient

terms which by our scaling (see equation 1-38) are of O(1); purely

geostrophic flows then break down. Thus in a thin layer close to the

boundary, the small Ev multiplies

𝜕

𝜕𝑧

(𝐾𝑀

𝜕(𝑢,𝑣)

𝜕𝑧

) to make their product O(1).

We express this mathematically by changing the coordinate z to , where

=

𝑧

(1-44)

1/2

𝐸v

so that the shear terms become

𝐸𝑣 𝜕

2

(𝐾𝑀

𝜕𝑧

𝜕(𝑢,𝑣)

𝜕𝑧

1 𝜕

) = 2 𝜕 (𝐾𝑀

𝜕(𝑢,𝑣)

𝜕

(1-45)

),

which is of O(1). The heuristic interpretation is, since

𝜕

𝜕𝑧

(𝐾𝑀

𝜕(𝑢,𝑣)

𝜕𝑧

) is

large, of O(Ev-1), inside the boundary layer because a small change in z

results in a large change in (u, v), the change is made more gradual in the

stretched coordinate (i.e. ‘one moves more slowly’ in than in z) and one

can resolve or “see” the rapid velocity change so that the boundary condition

(1-40) (and a corresponding one at the surface, see below) can be satisfied.

The “z” measures distance changes outside the boundary layer, i.e. “z” is an

outer coordinate (see equation 1-37a, in which the dimensional z* (where

the asterisk denotes dimensional) is non-dimensionalized by the water depth

D >> boundary layer depth), and the geostrophic relation (1-41 through 143) is an outer solution, though at the moment an incomplete one. Inside

the boundary layer, vertical distances are measured by

scaled by a much

smaller (localized) length scale l* which from (1-44) is

1/2

𝑙 ∗ = 𝐷𝐸v

≪ 𝐷.

(1-46)

The is called an inner coordinate, and the solution to be derived below is

called an inner solution. Indeed, equation (1-38) belongs to a class of

problems that are amendable to solution by the singular perturbation

Page 29

methods, the early development and usage of which is in aerodynamics [van

Dyke, 1964].

With the new vertical scale l*, we have

𝜕w

𝜕𝑧

=

1 𝜕w

1/2

𝐸v

𝜕

, which would

appear to be much larger than (and therefore cannot be balanced by) the

horizontal divergence term

𝜕u

𝜕𝑥

+

𝜕v

𝜕𝑦

in the continuity equation (1-38a).

This apparent dilemma is resolved by recognizing that in actuality the

vertical velocity w is very small. Indeed, inside the boundary layer, the

continuity equation requires that W*/l* ~ U/L, where W* is the scale of w

inside the boundary layer; thus

𝑊 ∗~

𝑙 ∗𝑈

𝐿

1/2 𝐷𝑈

𝐿

= 𝐸v

1/2

(1-47)

= 𝐸v 𝑊

where we have used (1-46) and (1-37b; for W). Therefore, because of the

thinness of the boundary layer, hence a much smaller aspect ratio l*/L than

the D/L previously assumed in (1-37), the appropriate vertical velocity scale

W* is correspondingly much smaller, by O(Ev1/2), than the scale W that we

have assumed. In the absence of other processes, the reader should satisfy

himself or herself to show that w* is the scale of the vertical velocity that is

valid both inside and outside the boundary layer.

If we now write the newly rescaled vertical velocity 𝑤

̃ as

𝑤

̃ = w*/W* = w.W/W* = w/Ev1/2

using (1-47), the 𝑤

𝜕

𝜕𝑧

(1-48)

terms on the RHS of the momentum equations (1-

38b,c) become:

𝑤

𝜕(𝑢,𝑣)

𝜕𝑧

=𝑤

̃

𝜕(𝑢,𝑣)

(1-49)

𝜕

and equation (1-38) becomes:

𝜕𝑢

+

𝜕𝑥

𝜕𝑣

𝜕𝑦

𝜕u

+

̃

𝜕𝑤

𝜕u

𝜕

(1-50a)

=0

𝜕u

𝜕𝑢

1 𝜕𝑝′

( 𝜕𝑡 + 𝑢 𝜕𝑥 + 𝑣 𝜕𝑦 + 𝑤

̃ ) = 𝑓𝑣 −

𝜕

𝜕𝑥

𝑜

𝜕v

𝜕v

𝜕v

𝜕𝑣

1 𝜕𝑝′

(𝜕𝑡 + 𝑢 𝜕𝑥 + 𝑣 𝜕𝑦 + 𝑤

̃ ) = −𝑓𝑢 −

𝜕

𝑜

𝜕𝑝′

𝜕

=0

+

𝜕𝑦

1 𝜕

𝜕𝑢

(𝐾𝑀 𝜕 )

2 𝜕

+

1 𝜕

𝜕𝑣

(𝐾𝑀 𝜕 )

2 𝜕

(1-50b)

(1-50c)

(1-50d)

Page 30

where (1-45) has been used in the viscous shear terms in (1-50b,c), f = ±1

for constant Coriolis and the hydrostatic relation is unchanged but for a

trivial change of the vertical coordinate. Because of (1-50d) (or 1-38d), the

thinness of the boundary layer means that the pressure-gradient force (per

unit mass), (p’/x, p’/y)/o, may be represented by their values just

outside the boundary layer in the geostrophic interior of the water column,

i.e., by f(vg, ug) from (1-41) (f = ±1).

Now that equation (1-50) is properly scaled for flows inside the

boundary layer, we may simplify it (as we did with equation (1-38) when

deriving the geostrophic relation) by dropping the terms involving :

𝜕𝑢

𝜕𝑥

+

𝜕𝑣

𝜕𝑦

+

̃

𝜕𝑤

𝜕

(1-51a)

=0

0 = 𝑓(𝑣 − 𝑣𝑔 ) +

1 𝜕

𝜕𝑢

(1-51b)

(𝐾𝑀 𝜕 )

2 𝜕

0 = −𝑓(𝑢 − 𝑢𝑔 ) +

1 𝜕

𝜕𝑣

(1-51c)

(𝐾𝑀 𝜕 )

2 𝜕

where (1-41) has been used in (1-51b,c) to replace the pressure-gradient

terms by the geostrophic velocity. Also, for constant Coriolis, f = ±1,

where the first (second) or top (bottom) sign of or applies to the

northern (southern) hemisphere with positive (negative) Coriolis.

Note that

since (ug, vg) is independent of z (or ), the (u, v) appearing in the derivatives in equations (1-51b,c) may be replaced by

(uE, vE) = (u-ug, v-vg),

(1-52)

the Ekman velocity; this is in fact what we will do below.

A wind stress is applied at the surface, and the boundary condition in

dimensional form is:

𝐾𝑀∗

𝜕(𝑢∗ ,𝑣 ∗ )

𝜕𝑧 ∗

= (𝑋𝑠∗ , 𝑌𝑠∗ ), at z* = 0

(1-54)

where the kinematic wind stress (Xs*, Ys*) = (o*/o) (Xs, Ys), and o* is the

scale of the wind stress in N m-2. In non-dimensional form, (1-54) is:

𝐾𝑀

𝜕(𝑢,𝑣)

𝜕

= 𝛼(𝑋𝑠 , 𝑌𝑠 ) = 𝛼𝝉𝑠 ,

at 𝜁 = 0

(1-55a)

Page 31

where s = (Xs, Ys) is the non-dimensionalized kinematic wind stress, and

𝛼=

𝑜∗ 𝐷

𝑜 𝑈𝐾

1/2

𝐸𝑣 .

(1-55b)

The boundary condition at the bottom is the no-slip condition:

at z = H

(u, v) = (0, 0),

(1-56)

Surface Boundary Layer with Constant Eddy Viscosity:

We assume constant eddy viscosity KM (= 1, non-dimensional), and

also that the depth of the channel is sufficiently deep that the surface and

bottom boundary layers do not interact. Equations (1-51b,c) are solved by

first re-writing them in terms of A = uE + ivE, where i = (1). Thus {(151c) i (1-51b)} gives (for f = ±1):

𝑖𝐴 =

1 𝜕2 𝐴

2 𝜕 2

.

(1-57)

We first consider the surface boundary layer, for which the solution that

satisfies (1-55a) and that vanishes as ~ (so that u ~ ug and v ~ vg as one

moves into the geoestrophic region outside the boundary layer) is:

𝑢𝐸 + 𝑖𝑣𝐸 =

𝛼

2

(1 − 𝑖)(𝑋𝑠 + 𝑖𝑌𝑠 )𝑒𝑥𝑝[(1 𝑖)]

(1-58)

or,

𝑢𝐸 =

𝑣𝐸 =

𝛼𝑒 𝜁

√2

𝛼𝑒 𝜁

√2

𝜋

𝜋

[𝑋𝑠 sin (𝜁 + ) 𝑌𝑠 cos (𝜁 + )]

4

4

𝜋

(1-59a)

𝜋

[ 𝑋𝑠 cos (𝜁 + ) + 𝑌𝑠 sin (𝜁 + )]

4

4

(1-59b)

In dimensional form, equation (1-59a,b) are:

𝑢𝐸∗ =

𝑣𝐸∗ =

𝑒𝜁

√𝐾𝑓𝑜

𝑒𝜁

√𝐾𝑓𝑜

𝜋

𝜋

[𝑋𝑠∗ sin (𝜁 + ) 𝑌𝑠∗ cos (𝜁 + )]

4

4

𝜋

𝜋

[ 𝑋𝑠∗ cos (𝜁 + ) + 𝑌𝑠∗ sin (𝜁 + )]

4

4

(1-60a)

(1-60b)

1/2

where = 𝑧 ∗ /(𝐷𝐸𝑣 ) = 𝑧 ∗ /√2𝐾/𝑓𝑜 . Equation (1-59) shows that over a

distance of about

E* = l* = √2𝐾/𝑓𝑜

(1-61)

Page 32

the velocity profiles (u, v) ~ (ug, vg), the geostrophic velocity in the ocean’s

The E* is called the Ekman depth; it

interior outside the boundary layer.

measures the thickness of the boundary layer which is therefore thicker for

larger K and/or smaller fo. At the surface, = 0, the vector product (uE,

vE) (Xs, Ys) gives the angle w between the velocity (uE, vE) and wind-stress

vector (Xs, Ys) as:

w = sin-1[cos(/4)] = /4;

(1-62)

the positive (negative) sign is for the northern (southern) hemisphere and it

means that the Ekman velocity is directed to the right (left) of the wind

stress, at an angle of 45o.

To obtain w, we use the continuity equation (1-51a), and also (1-59):

−

̃

𝜕𝑤

𝜕

=

𝛼𝑒 𝜁

√2

𝜋

𝜋

[(∇ ∙ 𝝉𝑠 ) sin (𝜁 + ) 𝒌(∇ × 𝝉𝑠 ) cos (𝜁 + )] (1-63)

4

4

0

which gives upon integration ∫𝜁 𝑑𝜁′ and setting 𝑤

̃(𝑥, 𝑦, 0) = 0:

𝛼

𝑤

̃(𝑥, 𝑦, 𝜁) = [−𝑒 𝜁 (∇ ∙ 𝝉𝑠 ) sin 𝜁 𝒌(∇ × 𝝉𝑠 ) (1−𝑒 𝜁 cos ζ)] (1-64a)

2

In dimensional form, using equation (1-48), we have:

𝑤∗ =

1

𝑓𝑜

[−𝑒 𝜁 (∇∗ ∙ 𝑠∗ ) sin 𝜁 𝒌(∇∗ × 𝑠∗ ) (1−𝑒 𝜁 cos ζ)]

(1-64b)

where = z*/(2K/fo)1/2.

Outside the surface boundary layer, ~ , the vertical velocity is:

𝑤

̃(𝑥, 𝑦, 𝜁~ − ) = 𝛼 𝒌(∇ × 𝝉𝑠 )/2

(1-65)

In terms of the original variables “w” and “z,” we note from equation (1-44)

that the ~ means a finite but small z-distance below the surface, i.e.

~ is equivalent to z ~ 0 and Ev1/2 << 1,

(1-66)

so that:

1/2

𝑤(𝑥, 𝑦, 𝑧~0− ) = 𝛼𝐸𝑣 𝒌(∇ × 𝝉𝑠 )/2

(1-67a)

Page 33

In dimensional form, this is:

𝑤 ∗ (𝑥, 𝑦, 𝑧~0− ) =

1

𝑓𝑜

𝒌(∇∗ × 𝑠∗ )

(1-67b)

Equation (1-67) is the main result from the analysis of surface boundary

layer: the effect of the wind is to induce a small vertical velocity which is

directly proportional to the wind stress curl:

𝒌(∇ × 𝝉𝑠 ) =

𝜕𝑌𝑠

𝜕𝑥

−

𝜕𝑋𝑠

𝜕𝑦

(1-68)

For positive wind stress curl, there is upwelling (downwelling) in the

northern (southern) hemisphere. The vertical velocity is small, but as we

shall see in a simple example, it has a profound effect on the interior flow

field. Before we give this example, it is necessary to conduct a similar

analysis on the bottom boundary layer near z =H.

Bottom Boundary Layer with Constant Eddy Viscosity:

The analysis for the bottom boundary layer follows much the same

way as for the surface layer. Instead of the wind-stress condition (1-55),

we now apply the no-slip condition (1-56). Let

zb = z + H

(1-69)

where the subscript “b” (here and below) is used to denote the bottom

boundary layer, to distinguish the solution from that obtained previously for

the surface boundary layer. The bottom boundary layer is near zb > 0.

Equation (1-56) then becomes:

(u, v) = (0, 0),

at zb = 0

The boundary-layer coordinate (1-44) becomes:

𝑏 =

𝑧𝑏

1/2

𝐸v

=

𝑧+𝐻

1/2

𝐸v

(1-70)

(1-71)

Equation (1-57) is the same, but a solution that decays as b ~ + is chosen:

uEb + i vEb = (ug + i vg) exp[(1 i)b ]

(1-72)

which also satisfies the no-slip condition (1-70). Thus,

𝑢𝐸𝑏 = 𝑒 −𝜁𝑏 [−𝑢𝑔 cos 𝜁𝑏 𝑣𝑔 sin 𝜁𝑏 ]

(1-73a)

𝑣𝐸𝑏 = 𝑒 −𝜁𝑏 [±𝑢𝑔 sin 𝜁𝑏 − 𝑣𝑔 cos 𝜁𝑏 ]

(1-73b)

Page 34

and the corresponding dimensional form simply has the u’s and v’s replaced

by corresponding variables with asterisks:

∗

𝑢𝐸𝐵

= 𝑒 −𝜁𝑏 [−𝑢𝑔∗ cos 𝜁𝑏 𝑣𝑔∗ sin 𝜁𝑏 ]

(1-74a)

∗

𝑣𝐸𝐵

= 𝑒 −𝜁𝑏 [±𝑢𝑔∗ sin 𝜁𝑏 − 𝑣𝑔∗ cos 𝜁𝑏 ]

(1-74b)

The vertical velocity is again obtained from the continuity equation (1-51a),

and also (1-73):

̃𝑏

𝜕𝑤

𝜕𝑏

= 𝑒−𝜁𝑏 [ 𝒌(∇ × 𝒖𝑔 ) sin 𝜁𝑏 ]

(1-75)

𝜁

which gives upon integration ∫0 𝑏 𝑑𝜁′ and setting 𝑤

̃ 𝑏 (𝑥, 𝑦, 0) = 0:

1

𝑤

̃ 𝑏 (𝑥, 𝑦, 𝜁𝑏 ) = [1 − 𝑒 −𝜁𝑏 (sin 𝜁𝑏 + cos 𝜁𝑏 )]𝒌(∇ × 𝒖𝑔 )

2

(1-76a)

In dimensional form, using equation (1-48), we have:

𝐾

𝑤𝑏∗ = √ [1 − 𝑒 −𝜁𝑏 (sin 𝜁𝑏 + cos 𝜁𝑏 )]𝒌(∇∗ × 𝒖𝑔∗ )

2𝑓

o

(1-76b)

where b = (z*+H*)/(2K/fo)1/2.

In terms of the original variables “w” and “z,” we note from equation

(1-71) that the b ~ + means a finite but small z-distance above the bottom,

i.e.

b ~ + is equivalent to zb ~ 0+, or z = H+ and Ev1/2 << 1,

(1-77)

so that (1-76a) and (1-48) give:

1/2

𝑤(𝑥, 𝑦, 𝑧~−𝐻 + ) = 𝐸𝑣 𝒌(∇ × 𝒖𝑔 )/2

(1-78a)

In dimensional form, this is:

𝑤 ∗ (𝑥, 𝑦, 𝑧 ∗ ~−𝐻∗+ ) == √

𝐾

2𝑓o

𝒌(∇∗ × 𝒖𝑔∗ )

(1-78b)

Equation (1-78) is the main result from the analysis of bottom boundary

layer. Unlike the surface boundary layer, it is the interior geostrophic flow

that is driving the bottom boundary layer. In the northern (southern)

hemisphere, a positive curl in the geostrophic velocity produces upwelling.

Page 35

A Simple Problem: Quasi-Geostrophic Interior Solution:

Equipped with the above boundary-layer formulae, we are now ready

to revisit the interior flow and attempt to close the otherwise indeterminate

(geostrophic) solution (equations 1-41 through 1-43). The correctly scaled

equation that governs the interior flow is (1-38). We will find an

approximate solution which as will become clear is called quasi-geostrophic.

We already saw that a first approximation is the geostrophic relation, and

indicated that the solution in Figure 1-8 was obtained through the inclusion

of small terms on the left-hand-side of the momentum equations. These

small terms represent small imbalances to the purely geostrophic relation.

Equations (1-38b,c) suggest then that the “degree” of this imbalance, or

ageostrophy, is of O(). It is reasonable to assume then that the solution

consists of predominantly the geostrophic part, plus a small correction that is

of O():

u = ug + u1 + O(2);

v = vg + v1 + O(2); etc.

and similarly for other variables also.

(1-79)

Higher order correction terms , O(2)

and higher are also indicated in equation (1-79), since there is no reason to

expect that the geostrophic relation plus the O() correction (i.e. u1 etc) will

provide the complete solution. It is important to understand that just as the

(ug, vg, …) are properly scaled of O(1), the (u1, v1, …), (u2, v2, …), etc are

also all scaled to be of O(1). Only then it makes sense to assume the form

of (1-79) for (u, v, …). Equation (1-79) is called a perturbation expansion,

which by the way may not be necessarily convergent [van Dyke, 1964].

From the discussion prior to Figure 1-8 (Taylor-Proudman Theorem) the

geostrophic velocity components are all independent of z: (ug,vg,wg)/z =

(0, 0, 0). In particular, for “w,” we already know from the boundary-layer

solutions at either the surface or the bottom boundary (see 1-67a and/or 178a) that w ~ O(Ev1/2).

Therefore, since Ev1/2 << 1 ~ O() say, the

corresponding expansion (i.e. 1-79) for w = wg + w1 + … shows that

wg = 0,

for all z;

(1-80)

Page 36

otherwise, the solution for w will be inconsistent with its small values near

the surface and bottom boundaries. In quasi-geostrophic approximations,

the vertical velocity component is very small, O(; Ev1/2), and represents

only the ageostrophic portion of the flow. However, this ageostrophy is

very important.

Substituting (1-79) into (1-38b,c), and collecting and equating terms

that are of O(1) and O() separately we obtain for the O(1) terms the

geostrophic relation as before, while the O() terms give:

𝜕𝑢1

𝜕𝑥

𝜕 𝑢𝑔

𝜕𝑡

𝜕𝑣𝑔

𝜕𝑡

𝜕𝑝′1

𝜕𝑧

+

𝜕𝑣1

𝜕𝑦

+ 𝑢𝑔

+ 𝑢𝑔

+

𝜕 𝑢𝑔

𝜕𝑥

𝜕𝑣𝑔

𝜕𝑥

𝜕𝑤1

𝜕𝑧

+ 𝑣𝑔

+ 𝑣𝑔

𝜕 𝑢𝑔

𝜕𝑦

𝜕𝑣𝑔

𝜕𝑦

= 𝑓 𝑣1 −

= −𝑓𝑢1 −

1 𝜕𝑝1′

(1-81b)

𝑜 𝜕𝑥

1 𝜕𝑝1′

(1-81c)

𝑜 𝜕𝑦

(1-81d)

=0

Note that the viscous terms

terms 𝑤𝑔

(1-81a)

=0

𝜕(𝑢𝑔 ,𝑣𝑔 )

𝜕𝑧

𝐸𝑣 𝜕

2

[𝐾𝑀

𝜕𝑧

𝜕 (𝑢𝑔 ,𝑣𝑔 )

𝜕𝑧

] and the vertical advection

are missing in (1-81) because

𝜕(𝑢𝑔 ,𝑣𝑔 )

𝜕𝑧

= (0,0) of course,

but in the latter case also because wg = 0 from (1-80). Thus the O()

dynamics are also hydrostatic and incompressible, but are not in perfect

geostrophic balance. The ageostrophy is due to the unsteadiness and

advective terms by the geostrophic flow (i.e. the left-hand-side of 1-81b,c).

We eliminate the pressure gradients from (1-81) by subtracting the yderivative of (1-81b) from the x-derivative of (1-81c), i.e. by [(181c)/x(1-81b)/y], and using (1-42) and also (1-81a):

𝜕 𝑔

𝜕𝑡

+ 𝑢𝑔

𝜕 𝑔

𝜕𝑥

+ 𝑣𝑔

𝜕𝑔

𝜕𝑦

=𝑓

𝜕 w1

𝜕𝑧

(1-82)

Page 37

where g = vg/xug/y is the relative vorticity of the geostrophic flow (not

to be confused with the scaled vertical coordinate of the boundary layer,

e.g. equations (1-44) or (1-71)). Since g is also independent of z, equation

0

(1-82) can be integrated ∫−𝐻 𝑑𝑧 to yield, upon using (1-67a) and (1-78a):

𝜕 𝑔

𝜕𝑡

+ 𝑢𝑔

𝜕 𝑔

𝜕𝑥

+ 𝑣𝑔

𝜕𝑔

𝜕𝑦

1/2

=

𝑓𝐸𝑣

𝐻2𝜖

[α𝒌(∇ × 𝝉𝑠 ) − 𝑔 ]

(1-83)

Given the wind stress curl, s, this equation now allows the determination

of the geostrophic vorticity field g, hence also the geostrophic velocity (ug,

vg). It is the consideration of the viscous boundary layers near the surface

(providing the wind stress curl) and also near the bottom (providing the

‘damping’, g) that allows the existence of a small vertical velocity and the

determination of the O(1) geostrophic field.

illustrates these ideas.

A simple example further

A simple problem:

Consider a homogeneous fluid in a channel of constant depth = H that

extends to in the x-direction; all fields (and forcing) are assumed

independent of the y-direction. A y-directed kinematic wind stress s = (Xs,

Ys) is applied at the surface:

(Xs, Ys) = (0, x)

(1-84a)

The solution is seeked only in the region L* x* +L*, where L* = 500 km,

or in terms of the non-dimensional “x,” in 1 x +1. Taking the scale of

the kinematic wind stress o*/o = 10-4 m2 s-2:

(𝑋𝒔∗ , 𝑌𝒔∗ ) = (0, 10−4 )𝑥 ∗ /𝐿∗

𝑚2 𝑠 −2 ;

(1-84b)

Page 38

we then have wind stresses of about 0.1 N m-2 at x* = 500 km. Since the

flow is independent of y, the geostrophic relation (1-41) requires that ug = 0.

Assuming also steady state, the LHS of equation (1-83) is then zero, yielding

the simple solution:

𝑔 = α𝒌(∇ × 𝝉𝑠 )

(1-85a)

or in dimensional form:

2

(𝑢𝑔∗ , 𝑣𝑔∗ ) = √𝑓 𝐾 (𝑋𝒔∗ , 𝑌𝒔∗ )

o

(1-85b)

The solution (equation 1-85) states a simple balance between the applied

wind stress at the surface and the frictional damping dues to the viscous

effects at the bottom. Knowing the geostrophic velocity in the interior, the

complete solution is supplemented near the surface by equations (1-59) and

(1-64a) (or in dimensional forms, equations 1-60 and 1-64b) and near the

bottom by equations (1-73) and (1-76a) (or in dimensional forms, equations

1-74 and 1-76b). Some details of this solution are given in Figures 1-9 and

1-10 (see exercises).

Exercise 1-3A: Use POM to solve the simple problem (above) of winddriven flow in a channel. (See Figures 1-9 and 1-10). Modify the code to

solve also the case with no-slip conditions at the bottom, and replot the

figures for this latter case.

Exercise 1-3B: Use POM to solve the Taylor-Proudman column (Figure

1-8). Note that in this case POM is modified without vertical viscosity.

Solve also the case of a seamount instead of the cylinder.

Exercise 1-3C: Use POM to solve a case that has wind as well as the

seamount: i.e. a combination of exercises 1-3A and 1-3B above. Derive

the corresponding analytical solution.

Page 39

Figure 1-9. Nearly-steady homogeneous (constant-density) wind-driven

rotational flow in a channel of depth 200m and theoretically unbounded in x,

but in practice an x-length = 1000 km is used in the solution. The flow is

assumed independent of y. The wind stress is specified in y-direction only:

(0, 10-4).(x/500km 1) m2 s-2. Panel (A) is for the y-directed velocity and

panel (B) the x-directed velocity. In (B), profiles of u are also plotted at

the four indicated x-locations with scales 0.1 m/s given along the bottom

for the first and fourth locations. Detailed plots comparing the profile at

x=205 km (i.e. the first x-location) with analytical solution are given in

Figure 1-10. The Coriolis parameter is constant, fo = 610-5 s-1, and the

vertical eddy viscosity is also constant, K = 510-3 m2 s-1. This numerical

solution is at time = 100 days, and differs slightly from the analytical one

discussed in the text; instead of the no-slip condition at the bottom, a

Page 40

matching of the velocity to the law-of-the-wall log layer is used [see the

POM manual by Mellor, 2004].

Page 41

Figure 1-10. Profiles of (A) u, (B) v and (C) w at the x = 205 km location

described in Figure 1-9b. Solid line indicates analytical solution assuming

no-slip condition at the bottom, while dashed line the corresponding

numerical (i.e. Figure 1-9) solution assuming log-layer at the bottom.

Black line indicates the Ekman velocity while red (in panels (A) and (B))

indicates the total (Ekman + geostrophic) velocity. Note that in panel (B),

total v/4 is plotted (so the profile fits in the same panel).

Page 42

CHAPTER 2: Wind-Driven Homogeneous Ocean: Boundary Currents

In this chapter we study the effects of wind on the general circulation of the

ocean. We will examine how the large-scale oceanic gyre may be explained by the

theories of Sverdrup [1947], Stommel [1948] and Munk [1950]. The circulation

consists of a slow equatorward drift in the mid-ocean and over the eastern portion of the

ocean basin, and a swift and narrow poleward current along the western boundary. We

then numerically simulate these large-scale features with simple model experiments using

POM. We will compare the numerical results against theories.

We still assume that the fluid is homogeneous ( = constant), and that the motions

have horizontal scales much larger than the vertical scales; in other words, we still

assume that the hydrostatic equation (1-30c) is satisfied. In fact the scales are so large

(~1000 km’s) that the Coriolis parameter “f” is no longer a constant, i.e. equation (1-37d)

is not valid, and

f = 2.sin(), /2 +/2

(2-1)

can be a function of the latitude

2-1: The -plane & the QG-Potential Vorticity Equation

For the moment, unprimed symbols are dimensional variables; primed symbols

(such as u’ etc) denote dimensionless variables. Suppose we focus on a certain latitude,

= o where f = fo, and let “y” be the northward (distance) coordinate measured from this

latitude (so that y = yo at = o), then for “small” distances away from this latitude, we

have:

f fo + [df/dy][yyo] = fo + [(df/d)/ro][yyo] = fo + [2.cos(o)/ro][yyo]

(2-2)

or,

f fo + o(yyo)

(2-3a)

o = 2.cos(o)/ro

(2-3b)

where

Page 43

Equation (2-3) constitutes the so called “-plane,” and is valid for |yyo| not too large (i.e.

a few thousands of kilometers, for o 2×10-11 m-1s-1 near mid-latitude.) We now

derive a vorticity equation similar to equation (1-82) but taking into account that f is a

function of y, i.e. is given by (2-3). In terms of dimensionless variables, denoted by

primes, (2-3) is:

f’ f’o + ’(y’y’o),

’ = (oL/|fo|) << 1.

(2-4)

where f’o = fo/|fo| = ±1 denotes northern or southern hemisphere. Note that ’ is small;

we will in fact let ’ , and from (1-39):

= ’/ = oL2/U O(1).

(2-5)

With (2-4), the Coriolis terms in equation (1-38) (which is dimensionless) becomes:

f'v’ = [f’o + ’(y’y’o)][v’g + v’1 + O(2)]

= f’ov’g + f’ov’1 + ’(y’y’o) v’g + O(’, 2)

(2-6a)

f'u’ = f’ou’g f’ou’1 ’(y’y’o) u’g + O(’, 2)]

(2-6b)

With these expressions, substituting (1-79) into (1-38b,c), and collecting and equating

terms that are of O(1) and O(, ) separately we obtain for the O(1) terms the geostrophic

relation as before, while the O(, ) terms give (c.f. equation 1-81):

𝜕𝑢1

𝜕𝑥

𝜕𝑢𝑔

𝜕𝑡

𝜕𝑣𝑔

𝜕𝑡

𝜕𝑝1′

𝜕𝑧

+

𝜕𝑣1

𝜕𝑦

+ 𝑢𝑔

+ 𝑢𝑔

=0

+

𝜕𝑤1

𝜕𝑢𝑔

𝜕𝑥

𝜕𝑣𝑔

𝜕𝑥

𝜕𝑧

=0

+ 𝑣𝑔

+ 𝑣𝑔

𝜕𝑢𝑔

𝜕𝑦

𝜕𝑣𝑔

𝜕𝑦

(2-7a)

1 𝜕𝑝1′

= 𝑓𝑜 𝑣1 + (y − 𝑦𝑜 )𝑣𝑔 −

𝜕𝑥

𝑜

1 𝜕𝑝1′

= −𝑓𝑜 𝑢1 − (y − 𝑦𝑜 )𝑢𝑔 −

𝑜

𝜕𝑦

(2-7b)

(2-7c)

(2-7d)

where fo = ±1, = ’/, and dimensionless variables are now unprimed (except for the

perturbation pressure p’1). Taking the curl, i.e. [(2-7c)/x(2-7b)/y] now gives

(instead of 1-82):

Page 44

𝑑𝑔

𝑑𝑡

+ 𝑣𝑔 = 𝑓𝑜

𝜕w1

(2-8a)

𝜕𝑧

where

𝑑

=

𝑑𝑡

𝜕

𝜕

𝜕

+ 𝑢𝑔 𝜕𝑥 + 𝑣𝑔 𝜕𝑦

𝜕𝑡

(2-8b)

0

Since (ug, vg) hence g are independent of z, equation (2-8) can be integrated ∫−𝐻 𝑑𝑧 to

yield, upon using (1-67a) and (1-78a) (c.f. 1-83):

𝑑𝑔

𝑑𝑡

+ 𝑣𝑔 =

1/2

𝑓𝑜 𝐸𝑣

2𝐻𝜖

[α𝒌(∇ × 𝝉𝑠 ) − 𝑔 ]

(2-9)

In dimensional form [with asterisks *; using (1-39) and (1-55b)], this is:

𝑑∗g

𝑑𝑡 ∗

+ ∗o 𝑣g∗ = (𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑙𝑧∗ 𝝉∗𝑠 − 𝑟 ∗ ∗g )/𝐷∗

(2-10)

where 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑙𝑧∗ 𝝉∗𝑠 is the z-component of the curl of the kinematic wind stress 𝝉∗𝑠 (see

equation 1-55a) and

1/2

𝑟 ∗ = 𝐸∗ 𝑓o∗ /2; 𝐸∗ = 𝑙 ∗ = 𝐷∗ 𝐸v

(2-11)

is the bottom friction coefficient; l* is the Ekman depth (from 1-46); note that an asterisk

has been placed on D, i.e. D* to avoid confusion with non-dimensional variables.

2-2: A Model of Large-Scale Ocean Gyre & Western Boundary Current

In this section, unless otherwise stated, all variables will be dimensional.

Consider a “box” ocean with sides Lx and Ly on a -plane (Figure 2-1). A zonal wind

stress is applied:

𝝉𝑤 = (−𝜏𝑤𝑜 cos(𝑦/𝐿𝑦 ), 0)

so that

(2-12)

Page 45

𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑙𝑧 (𝝉𝑤 ) = −(𝜏𝑤𝑜 /𝐿𝑦 )sin(𝑦/𝐿𝑦 )

(2-13)

where wo (which will be set = 10-4 m2s-2 below) is the magnitude of the (kinematic) wind

stress. Initially, the fluid is at rest:

(u, v, w) = (0, 0, 0), and also, free surface = 0

(2-14)

At the four side walls, both the normal and tangential components of the horizontal

velocities are zero:

(u, v) = (0, 0) at x = 0, x = Lx and also at y = 0, y = Ly.

(2-15)

At the ocean bottom and at the free surface, equations (1-31) are satisfied:

𝑤=

𝜕

𝜕𝑡

𝜕

𝜕

+ 𝑢 𝜕𝑥 + 𝑣 𝜕𝑦 , 𝑎𝑡 𝑧 = (𝑥, 𝑦, 𝑡),

𝜕𝐻

𝜕𝐻

𝑤 = −𝑢 𝜕𝑥 − 𝑣 𝜕𝑦 ,

𝑎𝑡 𝑧 = −𝐻(𝑥, 𝑦).

(2-16a)

(2-16b)

The continuity equation and the x and y momentum equations are then (c.f. 1-35):

𝜕

𝜕𝑡

𝜕𝑈

𝜕𝑉

= − 𝜕𝑥 − 𝜕𝑦

(2-17a)

𝜕𝑢

𝜕

𝜕

𝜕𝑢

𝜕𝑣

𝜕

𝜕

𝜕𝑣

( 𝜕𝑡 ) = +𝑓𝑣 − 𝑔 𝜕𝑥 + 𝜕𝑧 (𝐾𝑀 𝜕𝑧 )

( 𝜕𝑡 ) = −𝑓𝑢 − 𝑔 𝜕𝑦 + 𝜕𝑧 (𝐾𝑀 𝜕𝑧 ).

(2-17b)

(2-17c)

where

(𝑈, 𝑉) = ∫−𝐻(𝑢, 𝑣)𝑑𝑧

(2-18)

is the depth-integrated transport vector (per unit length). These equations differ from

(1-35) in that the nonlinear advective terms in momentum equations (2-17b,c) have been

dropped.

Page 46

Figure 2-1. A “box” ocean circulation driven by eastward (northern half of basin) and

westward (southern half) wind stress distribution.

Depth-integrate (2-17b,c), and again drop nonlinear terms such as u etc:

𝜕𝑈

𝜕

𝜕𝑉

𝜕

𝑥

( 𝜕𝑡 ) = +𝑓𝑉 − 𝑔𝐻 𝜕𝑥 + 𝜏𝑤

− 𝜏𝑏𝑥

𝑦

𝑦

( 𝜕𝑡 ) = −𝑓𝑈 − 𝑔𝐻 𝜕𝑦 + 𝜏𝑤 − 𝜏𝑏

(2-19a)

(2-19b)

where w and b are wind and bottom stress vectors respectively. These equations

together with equation (2-17a) constitute there equation for three unknowns (, U, V).

For our purpose, it is more convenient to write them in terms of the depth-averaged

velocity:

0

(𝑢̅, 𝑣̅ ) = ∫−𝐻(𝑢, 𝑣)𝑑𝑧/𝐷 ∫−𝐻(𝑢, 𝑣)𝑑𝑧/𝐻 = (𝑈, 𝑉)/𝐻,

so that (2-17a) and (2-19) become:

(2-20)

Page 47

𝜕

𝜕𝑡

+

̅𝐻

𝜕𝑢

𝜕𝑥

+

𝜕𝑣̅ 𝐻

𝜕𝑦

=𝑄

̅

𝜕𝑢

𝜕

𝜕𝑣̅

𝜕

(2-21a)

𝑥

( 𝜕𝑡 ) = +𝑓𝑣̅ − 𝑔 𝜕𝑥 + (𝜏𝑤

− 𝑟𝑢̅)/𝐻

𝑦

( 𝜕𝑡 ) = −𝑓𝑢̅ − 𝑔 𝜕𝑦 + (𝜏𝑤 − 𝑟𝑣̅ )/𝐻

(2-21b)

(2-21c)

where r is the bottom friction coefficient with dimension m/s, we have modeled the

bottom friction as:

𝑦

(𝜏𝑏𝑥 , 𝜏𝑏 ) = 𝑟(𝑢̅, 𝑣̅ ),

(2-22)

and we have also added a source term Q to the right hand side of (2-21a). This we will

use later to model the net effect of precipitation (𝑃̇) minus evaporation (𝐸̇ ), i.e.

Q = (𝑃̇ – 𝐸̇ )/o (unit is m/s).

(2-23)

Let H = constant, a vorticity equation similar to (2-10) may now be derived from

(2-21). Taking the curl of (2-21b,c), we obtain:

𝜕̅

𝜕𝑡

𝜕

+ 𝑜 𝑣̅ − 𝑓 𝜕𝑡 /𝐻 = [𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑙𝑧 (𝝉𝑤 ) − 𝑄𝑓 − 𝑟̅]/𝐻

(2-24a)

Apart from the terms involving Q and /t, this equation is equivalent to (2-10). The

term /t does not appear in (2-10) because it is neglected when we derived the vertical

velocity at the surface (see equation 1-67). We will explain in the next section when

this term may be deleted; assuming that it can be, then (2-24a) becomes:

𝜕̅

𝜕𝑡

+ 𝑜 𝑣̅ = [𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑙𝑧 (𝝉𝑤 ) − 𝑄𝑓 − 𝑟̅ ]/𝐻

(2-24b)

The appearance of -Qf together with curlz(w) means that as far as the large-scale ocean

circulation is concerned, effects of wind stress curl and net precipitation minus

evaporation are equivalent. The reason is that in both cases, the ocean layer beneath the

surface boundary layer (where wind and precipitation etc act) ‘sees’ only vertical mass

flux coming in (or out) of the surface layer. In the case of wind stress curl, this is

“Ekman pumping” (Chapter 1) caused by convergence or divergence in the surface layer,

Page 48

while in the case of precipitation etc, it is more direct – due to the flux of water from the

atmosphere. We will model these effects and give a physical interpretation below.

Also, while H is the ocean depth, it may be (and for our purpose will be) interpreted as

the depth of the main thermocline in which the predominant large-scale currents reside.

̅ is then considered as the friction at the base of the main

In that case, the friction 𝑟𝒖

thermocline.

Sverdrup Relation:

In the open ocean away from side boundaries, the relative vorticity ̅ is assumed

weak, in fact ̅ 0, and the main vorticity balance in steady state is, from (2-24b)

(omitting Q for simplicity):

𝑜 𝑣̅ 𝐻 = 𝑜 𝑉 = 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑙𝑧 (𝝉𝑤 )

(2-25)

Figure 2-2. A schematic to explain the equatorward Sverdrup transport V caused by a

negative wind stress curl, curlz(w) < 0.

Page 49

Equation (2-25) is the Sverdrup relation; it shows that in steady motion, a negative

curlz(w) produces southward transport. Figure 2-2 explains the physics involved. The

negative curlz(w) produces convergent flow in the thin surface (Ekman) layer (Chapter 1)

and hence a downward pumping that squashes the vortex tube in the deeper interior; this

is equivalent to a divergent subsurface flow. Squashing increases the cross-sectional

area of the tube, and if it stays at the same latitude a negative relative vorticity (i.e. a

reduced spin) would be produced, ̅ < 0. To keep the same ̅ 0, and assuming that

the tube remains approximately vertical (and it does), the tube must move south along the

curved earth surface where it can stretch and retain its initial zero spin. The curved

surface in this case is the physical equivalence of the -effect, i.e. the Coriolis parameter f

varies with latitude. Gill [1982; p.465] gives another, equivalent explanation. The

divergent subsurface flow beneath the negative curlz(w) increases the cross-sectional

area of the vortex tube, so the absolute vorticity (i.e. f + ) decreases. But since f >> ,

the only way that this decrease can be accomplished is that the tube moves southward

where f is smaller.

Figure 2-2 illustrates two other features. One is that the effect of (positive) Q [=

(𝑃̇–𝐸̇ )/o] is similar to (negative) curlz(w): this is because Q ‘pumps’ water into the

subsurface layer and again squashes vortex tube. The other one is that while the surface

is slightly elevated ( > 0) it is not important in the argument given above; in steady

state, it is in fact = 0.

If as shown in Figure 2-1 the Sverdrup transport occurs over most portion of the

ocean basin, then the total southward transport is:

𝐿

SV ∫0 𝑥 𝑐𝑢𝑟𝑙𝑧 (𝝉𝑤 )/𝑜 𝑑𝑥

(m3 s-1).

(2-26)

Page 50

Figure 2-3. Annual mean distribution of Ekman pumping, positive = upwelling, in unit

of 10-6 m s-1 (or 0.1 m/day). From Tomczak and Godfrey.

Figure 2-3 shows a global map of Ekman pumping – note large areas of downwelling in

the subtropical regions, suggesting equatorward Sverdrup transports there. From (2-26),

𝑥

we have roughly SV curlz(w).Lx/o 2|𝜏𝑤

|Lx/(Lyo) (2×10-4/10-11)(Lx/Ly) m3 s-1

𝑥

20 Sv (1 Sv = 106 m3 s-1) for Lx Ly, |𝜏𝑤

| 10-4 m2 s-2 and o 10-11 m-1s-1. The

corresponding Ekman pumping (downwelling) is from (1-64b) = curlz(w)/fo

𝑥

2|𝜏𝑤

|/(Lyfo) 1~2×10-6 m s-1 for Ly 2000 km and fo 6×10-5 s-1, roughly equal to the

values shown in Figure 2-3. This Ekman velocity (or Figure 2-3) may be compared

with contours of Q [= (𝑃̇–𝐸̇ )/o] shown in Figure 2-4, which gives local maxima of

roughly 10-7 m s-1, about 10 times weaker than the Ekman pumping.

Page 51

Figure 2-4. Annual mean distribution of precipitation minus evaporation, Q = (𝑃̇–𝐸̇ )/o,

in m yr-1 ( 3×10-8 m s-1); shaded regions are positive.

Stommel’s Model of the Western Boundary Current (WBC):

In our idealized closed basin (Figure 2-1), the southward Sverdrup transport must

be returned northward. Since this return cannot be in the mid-ocean (i.e. open ocean)