The Development of the Freedom of Speech

advertisement

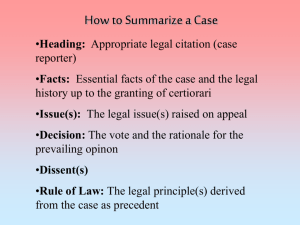

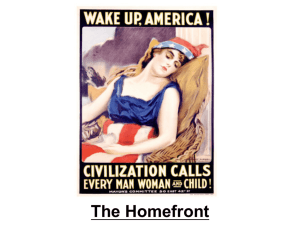

The Development of the Freedom of Speech GOVT 2305 In this section we trace the development of the freedom of speech, specifically the gradual allowance of individuals to engage in speech critical of government. This will set us up for a look at the way the Supreme Court handles free speech cases and then how public opinion evolves. This has occurred because over time the concept of sedition has been narrowed. And justifications for censorship have also been narrowed. We’ll look at both in this section – mostly the narrowing of sedition. Here are blog Tags taking you to the various posts I’ve complied over the years related to this section: Free Speech Freedom of Speech Marketplace of Ideas Sedition We will note that the freedom of speech is essential in a democracy and has allowed for public opinion to emerge as an external force on government. Let’s begin by reviewing the language of the First Amendment. “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” Remember from a previous section that this does not establish rights, it restricts legislative interference with certain rights. It removes these from the control the majority, meaning that they are intended to support the right of the minority. The carves out protections for two types of rights. Religious Political We covered religious freedoms in a previous sections. There are four specific types of political freedoms established. The freedom of speech solidified the right of people to not only speak freely but to influence others, thus influencing the course of public opinion which can in turn influence the direction of public policy. The freedom of the press allows for the development of communications mechanisms that can disseminate speech and provide information about public events without governmental interference. The right to peaceful assembly interest groups and political parties, in addition to the ability of people to meet and discuss politics – or anything else they choose – as they wish. The right petition for a redress of grievances allows for citizens to take an issue to their elected representatives, to engage in lobbying and other activities which allow for a direct interaction with government officials. None of these freedoms were fully recognized or protected in Britain or the American colonies prior to the Glorious Revolution, and were really only sporadically protected following that. Recall that the states had no obligation to recognize these rights until the 14th Amendment was ratified. Let’s dig into the development of the freedom of speech. Here is a critical consequence of Freedom of Speech: By allowing people to think freely, government allows citizens to form their own opinions and to be critical of it. They tend to not like that. Governments, historically, do not like to be criticized by their people, and often have not allowed it. Sedition and Seditious Libel have been punished over history, sometimes brutally. In law, sedition is overt conduct, such as speech and organization, that is deemed by the legal authority to tend toward insurrection against the established order. – Wikipedia. Seditious libel is defined as any spoken or written attempt to: • bring government into hatred or contempt • incites people to change government • promotes discontent among the citizens Relevant trivia: “The crime of seditious libel was defined and established in England during the 1606 case "De Libellis Famosis" by the Star Chamber. The case defined seditious libel as criticism of public persons, the government, or King.” – Wikipedia. Remember that we covered the Star Chamber previously when we looked at the judiciary. It was a court fully controlled by the king, and used to punish powerful opponents. Sedition allows them to be punished for what they say – especially if they say something negative about the monarch. Seditious libel "has always been an accordion-like concept, expandable or contractible at the whim of judges.“ - Leonard Levy. Sedition in its modern meaning first appeared in the Elizabethan Era (c. 1590) as the "notion of inciting by words or writings disaffection towards the state or constituted authority". "Sedition complements treason and martial law: while treason controls primarily the privileged, ecclesiastical opponents, priests, and Jesuits, as well as certain commoners; and martial law frightens commoners, sedition frightens intellectuals.“ - Wikipedia Free speech can undermine authority. Note that the previous section mentions that sedition is intended to frighten intellectuals. These people are responsible for the ideas that can challenge existing authority and propose new ways to organize societies; new ideas for governing. Remember this guy? In the early sections of this class we discussed John Locke’s First and Second Treatises on Government. The first argued against the divine right of the monarch. The second argued for governments based on the consent of the governed. Elizabeth I would call that sedition, if not outright treason. Sedition can go beyond articulating ideas that challenge authority. It can attempt to determine what thoughts one can hold. This occurred in Britain once monarchic power expanded over religion. When Henry VIII (1509 – 1547) became king he expanded the power (and resources) of the monarchy by replacing the Catholic Church with the Church of England. He named himself Supreme Head of the church. Loyalty to the king – including membership in the Church of England - became especially important given ongoing hostility with the Catholic Church. To be Catholic was to be considered a potential enemy of the monarch and traitor to England. Here’s a slide from a previous section in class: England moved into an era of "conformity of mind" with the new royal supremacy (much akin to the absolutism of France's Louis XIV): by 1536, all ecclesiastical and government officials were required to publicly approve of the break with Rome and take an oath of loyalty – Britannia.com To not conform was to a potential rebel. To articulate your opinions meant you were willing to act rebelliously. Like this guy: Meet Guy Fawkes You might be more familiar with this image: Or this one There was also no allowance for Freedom of Conscience, or Thought. A definition of the freedom of conscience: “the freedom of an individual to hold or consider a fact, viewpoint, or thought, independent of others' viewpoints.” Madison proposed the following language for the Bill of Rights: “No State shall violate the equal rights of conscience.” It was not approved by Congress The founders of the United States were clearly guilty of seditious libel. As were those of Texas. Had the revolution failed they would have faced severe punishment. "We must indeed all hang together, or most assuredly we shall all hang separately." Benjamin Franklin He meant that literally. The idea that people ought to be free to express their beliefs, even if they are critical of government began in late 17th Century Britain following the Glorious Revolution and the limitation of arbitrary monarchic power. Specifically it happened when the British Bill of Rights was signed by William and Mary. Remember that the purpose of the document was to place limits on the arbitrary power of the monarchy. This began a slow process where people were able to enjoy political freedoms. Here are a couple bits from the document: “. . . it is the Right of the Subjects to petition the King and all Commitments and Prosecutions for such Petitioning are Illegall.” “. . . the Freedome of Speech and Debates or Proceedings in Parlyament ought not to be impeached or questioned in any Court or Place out of Parlyament.” Spelling of course was a bit random back then. And a weird thing happened when these freedoms began to be established. Ideas began to flow freely in Britain, and the nation began to prosper. Ideas about religion, government, science, and all sorts of things began to be exchanged. Britain became a center of innovation. These freedoms arrived about the same time that coffee made an appearance in Britain. This helped loosen tongues. Click here for English coffeehouses. It also coincided with the Age of Enlightenment. Many early arguments in favor of free expression were found in Cato’s Letters These were essays that promoted expanded individual freedom, speech and conscience, and argued against tyranny. Cato’s Letter #15 Argued that the freedom of speech is inseparable from public liberty “SIR, Without freedom of thought, there can be no such thing as wisdom; and no such thing as publick liberty, without freedom of speech: Which is the right of every man, as far as by it he does not hurt and control the right of another; and this is the only check which it ought to suffer, the only bounds which it ought to know. . . . . . . This sacred privilege is so essential to free government, that the security of property; and the freedom of speech, always go together; and in those wretched countries where a man can not call his tongue his own, he can scarce call any thing else his own. Whoever would overthrow the liberty of the nation, must begin by subduing the freedom of speech; a thing terrible to publick traitors.” These authors were very influential in the American colonies and had an impact on the development of republican thought in the United States. It helps explain the system of government that was developed in the Constitution. Its also worth pointing out that the expansion of freedom – equally – to different groups in society over American History included the ability of these groups to speak freely. Meanwhile in the colonies, the definition of sedition was undergoing modification. That was the consequence of the trial of John Peter Zenger in 1735. Up to that time, any negative statement could be considered seditious, even if it was true. Zenger was a New York printer charged with sedition for printing negative stories about the Governor of the New York Province, William Cosby. He was arrested for seditious libel, but Zenger’s attorney – Andrew Hamilton - argued to the jury that the truth of the stories meant they should not be considered seditious. The jury agreed, and changed the meaning of sedition. Hamilton persuaded the jury to nullify existing sedition law and determine that the speaking and printing of the truth was not seditious. That said, sedition continued to be punished in the early years of the United States, and periodically afterwards. An early example was the Sedition Act, which was passed along with the Alien Act as a way the Federalists to try to push back against the growth of the DemocraticRepublican Party. We covered this a few sections back when we covered the party system in the US. Its full title was An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes against the United States (Sedition Act) Click here for the LOC page on it. Here’s the key section from the bill: And be it further enacted, That if any person shall write, print, utter or publish, or shall cause or procure to be written, printed, uttered or publishing, or shall knowingly and willingly assist or aid in writing, printing, uttering or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute; . . . . . . or to excite against them, or either or any of them, the hatred of the good people of the United States, or to excite any unlawful combinations therein, for opposing or resisting any law of the United States, or any act of the President of the United States, done in pursuance of any such law, or of the powers in him vested by the constitution of the United States, or to resist, oppose, or defeat any such law or act, . . . . . . or to aid, encourage or abet any hostile designs of any foreign nation against the United States, their people or government, then such person, being thereof convicted before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars, and by imprisonment not exceeding two years. Some people went to jail for violating the act, for example: Matthew Lyon and Benjamin Franklin Bache. But it would also lead to John Adam’s defeat in the 1800 election. It also led to the idea that one could oppose the president for political reasons, but this did not mean one was seditious or treasonous. This is alleged to be a fight in Congress over the Acts. The next major sedition act passed into law was the Sedition Act of 1918, which was passed in the waning days of WWI. “It forbade the use of "disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language" about the United States government, its flag, or its armed forces or that caused others to view the American government or its institutions with contempt. Those convicted under the act generally received sentences of imprisonment for 5 to 20 years.” It was sporadically enforced. Eugene Debs was among the people who served time for violating the law. Click here for a description of how the law was implemented in Montana. The Montana Sedition Project. The more significant arrests were made in New York when 5 people were prosecuted for printing and distributing circulars critical of the American involvement in WWI. This case would become known as Abrams v. United States. A description from the majority decision: “It was admitted on the trial that the defendants had united to print and distribute the described circulars and that 5,000 of them had been printed and distributed about the 22d day of August, 1918. The group had a meeting place in New York City, in rooms rented by defendant Abrams, under an assumed name, and there the subject of printing the circulars was discussed about two weeks before the defendants were arrested. The defendant Abrams, although not a printer, on July 27, 1918, purchased the printing outfit with which the circulars were printed, and installed it in a basement room where the work was done at night. The circulars were distributed, some by throwing them from a window of a building where one of the defendants was employed and others secretly, in New York City.” – Findlaw. Aside from stating that the accused did in fact violate the letter of the law, they suggested that by printing the circulars, they also posed an actual physical threat to the United States: “ . . . the language of these circulars was obviously intended to provoke and to encourage resistance to the United States in the war, as the third count runs, and, the defendants, in terms, plainly urged and advocated a resort to a general strike of workers in ammunition factories for the purpose of curtailing the production of ordnance and munitions necessary and essential to the prosecution of the war . . . “ Eight members of the court voted to uphold the decision, but one – Oliver Wendell Holmes – voted against it. His dissenting argument stated that since no actual harm was likely to happen due to the circulars, the defendants had the right to speak freely. Sedition must include the likelihood that harm will result from the speech. This marked a change for Holmes, he had previously written for the majority in Schenck v United States upholding a conviction under the 1917 Espionage Act. “The First Amendment did not protect speech encouraging insubordination, because, ‘when a nation is at war, many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.’” Here’s the key part of the Schencks decision. “We admit that in many places and in ordinary times the defendants in saying all that was said in the circular would have been within their constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. . . . The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. It does not even protect a man from an injunction against uttering words that may have all the effect of force. . . . . . . The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.” – Schenck v. US This is the famous falsely shouting fire in a crowded theater rule. It’s the classic example of unprotected speech. But Holmes changed his mind somewhat in Abrams. He started narrowing what it took to present a clear and present danger to the government which might justify restrictions on speech “It is only the present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about that warrants Congress in setting a limit to the expression of opinion where private rights are not concerned. Congress certainly cannot forbid all effort to change the mind of the country.” “I do not see how anyone can find the intent required by the statute in any of the defendant's words.” “In this case sentences of twenty years imprisonment have been imposed for the publishing of two leaflets that I believe the defendants had as much right to publish as the Government has to publish the Constitution of the United States now vainly invoked by them.” “Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power and want a certain result with all your heart you naturally express your wishes in law and sweep away all opposition...But when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas...that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out. That at any rate is the theory of our Constitution.” “It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment. Every year if not every day we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based upon imperfect knowledge. While that experiment is part of our system I think that we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death, unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purposes of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country.” “I had conceived that the United States through many years had shown its repentance for the Sedition Act of 1798 by repaying fines that it imposed. Only the emergency that makes it immediately dangerous to leave the correction of evil counsels to time warrants making any exception to the sweeping command, 'Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech.‘” “Of course I am speaking only of expressions of opinion and exhortations, which were all that were uttered here, but I regret that I cannot put into more impressive words my belief that in their conviction upon this indictment the defendants were deprived of their rights under the Constitution of the United States.” The Marketplace of Ideas Since this ruling mentions the concept of the marketplace of ideas, it’s worth digging a bit into it. It has a great degree of resonance in the public debate. Holmes’ position was based largely on the arguments made by John Stuart Mill in his 1859 book On Liberty – which itself is based on arguments made in Cato #15. The Harm Principle: “. . . the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others." The essence of the marketplace of ideas is that free open debate is necessary in order to either swap error for truth, or ensure a renewed appreciation for preexisting principles. It allows for a dynamic, rather than static, society. This can include ongoing discussions of the merit of different governing systems, and the pros and cons of different policy options. But these can sometimes be taken – for different reasons – to create a clear and present danger, fairly or unfairly. Here’s an extended quote on the thought taken from the Wikipedia pages on On Liberty. This addresses the question: How can challenging an idea be beneficial to society? First, if any opinion is compelled to silence, that opinion may, for aught we can certainly know, be true. To deny this is to assume our own infallibility. Secondly, though the silenced opinion be an error, it may, and very commonly does, contain a portion of truth; and since the general or prevailing opinion on any subject is rarely or never the whole truth, it is only by the collision of adverse opinions that the remainder of the truth has any chance of being supplied. Thirdly, even if the received opinion be not only true, but the whole truth; unless it is suffered to be, and actually is, vigorously and earnestly contested, it will, by most of those who receive it, be held in the manner of a prejudice, with little comprehension or feeling of its rational grounds. And not only this, but, fourthly, the meaning of the doctrine itself will be in danger of being lost, or enfeebled, and deprived of its vital effect on the character and conduct: the dogma becoming a mere formal profession, inefficacious for good, but cumbering the ground, and preventing the growth of any real and heartfelt conviction, from reason or personal experience. His basic point: There is never a jutifiable reason to suppress an opinion. The marketplace of ideas has to be open and broad. If opinions are not accepted in the marketplace of ideas, maybe it wasn’t a good one. Here’s a more recent expression of that idea: “Free speech is an indispensable tool of self-governance in a democratic society. Concurring in Whitney v. California (1927), Justice Louis Brandeis wrote that ‘freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth.’“ – Rodney Smolla A second point: The Tyranny of the Majority It also ties into John Stuart Mill’s take on the tyranny of the majority. Remember that this was also the subject of Federalist #10. In it James Madison promoted a republic on the national level because it was likely to break apart the majority faction so that would be unable to dominate the legislative process and impose the will of the majority upon the minority. More specifically it could not use its majoritarian power to undermine the rights of the minority. While Mill was also concerned about the ability of the majority to dominate public policy and suppress the rights of the minority, he was also concerned about the ability of the majority to – subtly (or not) – suppress the tendency of the minority to speak their minds. Click here for a website that does a pretty good job of outlining the issue: Here’s a quote from Mill highlighted by the site: Protection, therefore, against the tyranny of the magistrate is not enough: there needs protection also against the tyranny of the prevailing opinion and feeling; against the tendency of society to impose, by other means than civil penalties, its own ideas and practices as rules of conduct on those who dissent from them; to fetter the development, and, if possible, prevent the formation, of any individuality not in harmony with its ways, and compel all characters to fashion themselves upon the model of its own. This points out that in a democracy, the freedom of speech does not guarantee that all points of view will be expressed. Unpopular opinions can be subtly – or not so subtly – suppressed. Attempts can be made to protect expression, but sometimes these are not sufficient. Since the Supreme Court began taking the freedom of speech seriously since the early 20th Century, it has ruled on a series of cases that have involved this question. It can be best summarized as: How do we balance the extent of free speech against the greater interest of society? This is another way of asking: How does the court determine what speech is acceptable and what speech is not? We turn to that question in the section on Free Speech and the Supreme Court.