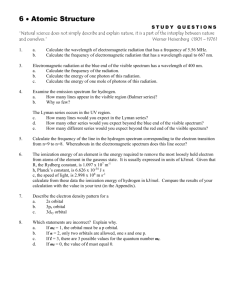

Jensen_Chapter02_CSUN_407

Wave Model of Electromagnetic Energy

An electromagnetic wave is composed of electric and magnetic vectors that are orthogonal to one another and travel from the source at the speed of light (3 x 10 8 m s -1 ).

Jensen, 2000

Spectral Bandwidths of Landsat and SPOT Sensor Systems

Jensen, 2000

Blackbody Radiation

Curves

Blackbody radiation curves for several objects including the Sun and the Earth which approximate 6,000 ˚K and 300 ˚K blackbodies, respectively. Notice that as the temperature of the object increases, its dominant wavelength shifts toward the short wavelength portion of the spectrum.

Jensen, 2000

Radiant Intensity of the Sun

The Sun approximates a 6,000 K blackbody with a dominant wavelength of 0.5 m (green light).

Earth approximates a 300 K blackbody with a dominant wavelength of 9.7 m . The 6,000 K

Sun produces 41% of its energy in the visible region from 0.4 - 0.7 m

(blue, green, and red light). The other

59% of the energy is in wavelengths shorter than blue light (<0.4 m) and longer than red light (>0.7 m). Eyes are only sensitive to light from the

0.4 to 0.7 m. Remote sensor detectors can be made sensitive to energy in the non-visible regions of the spectrum.

Jensen, 2000

Electromagnetic

Spectrum

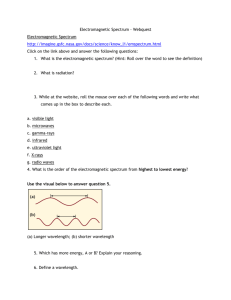

The Sun produces a continuous spectrum of energy from gamma rays to radio waves. The visible portion of the spectrum may be measured using wavelength

(measured in nanometers or micrometers, i.e. nm or m) or electron volts (eV) terminology.

All units are interchangeable.

Jensen, 2000

Particle Model of Electromagnetic Energy

Niels Bohr (1885-1962) and Max Planck recognized the discrete nature of exchanges of radiant energy and proposed the quantum theory of electromagnetic radiation . This theory states that energy is transferred in discrete packets called quanta or photons as discussed.

The relationship between the frequency of radiation expressed by wave theory and the quantum is:

Q = h where Q is the energy of a quantum measured in Joules (J), h is the

Planck constant (6.626 x 10 -34 J s -1 ), and is the frequency of the radiation.

Particle Model of Electromagnetic Energy

Referring to the previous formulas, we can multiply the equation by h/h, or

1, without changing its value:

= h c h

By substituting Q for h , we can express the wavelength associated with a quantum of energy as:

= h c / Q, or Q = h c /

Thus, the energy of a quantum is inversely proportional to its wavelength , i.e. the longer the wavelength involved, the lower its energy content.

The Energy of

Quanta (Photons)

The energy of quanta (photons) ranging from gamma rays to radio waves in the electromagnetic spectrum.

The Creation of Light

Creation of Light from Atomic Particles and the Photoelectric Effect

Electron

Proton

1

2

3

4

5

Ground state a.

Photon of light is absorbed

1

2

3

4

5

Excitation - photon is absorbed b.

1

2

3

Photoelectric effect d.

1

2

3

1

2

3

4

5

De-excitation - quantum leap c.

Photon of light is emitted when an electron drops from a higher energy state to a lower energy state

The emission of an electron carrying the same amount of energy

(a-c) A photon of electromagnetic energy is emitted when an electron in an atom or molecule drops from a higher energy state to a lower energy state. The type of light emitted (i.e. its wavelength) is a function of the changes in the energy levels of the outer, valence electron. (d) Matter can also be subjected to such high temperatures that electrons that normally move in captured, nonradiating orbits are broken free.

When this happens, the atom remains with a positive charge equal to the negatively charged electron which escaped. The electron becomes a free electron and the atom is called an ion.

If another free electron fills the vacant energy level created by the free electron, then radiation from all wavelengths is produced, i.e. a continuous spectrum of energy. The intense heat at the surface of the Sun produces a continuous spectrum in this manner.

The Creation of Light from Atomic Particles

The SodiumVapor Lamp

Atom's energy loss is 2.1 eV when an excited electron falls back to an orbit closer to the nucleus

Energy change in electron volts (eV)

Sodium

Atom

Emits a photon of yellow light (2.1 eV)

4

3

2

1

0

Electron

Orbit

Electron

Nucleus

Creation of Light

After being energized by several thousand volts of electricity, the outermost electron in each energized atom of sodium vapor climbs to a high rung on the energy latter and then returns down the ladder in a predictable fashion.

The last two rungs in the descent are 2.1 eV apart. This produces a photon of yellow light which has 2.1 eV of energy.

Atmospheric Scattering a.

Rayleigh Scattering

Gas molecule

Mie Scattering b.

Diameter

Smoke, dust

Non-Selective Scattering c.

Water vapor

Photon of electromagnetic energy modeled as a wave

Atmospheric

Scattering

The type of scattering is a function of:

• the wavelength of the incident radiant energy, and

• the size of the gas molecule, dust particle, or water vapor droplet encountered.

Intensity of Rayleigh Scattering

Varies Inversely with

3 2.75 2.5 2.25 2 1.75

100

Energy in electron volts (eV)

80

60

Rayleigh

Scattering

The intensity of Rayleigh scattering varies inversely with the fourth power of the wavelength ( -4 ).

40

20

V B G Y O R

0

0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7

Wavelength in Micrometers

Atmospheric Refraction

Incident radiant energy

Normal to the surface

Optically less dense atmosphere refraction for this layer of the atmosphere

Path of

energy in homogeneous atmos phere

Optically more dense atmosphere

Optically less dense atmosphere

Path of radiant energy affected by atmospheric refraction

Atmospheric

Refraction

Refraction in three non-turbulent atmospheric layers. The incident radiant energy is bent from its normal trajectory as it travels from one atmospheric layer to another. Snell's law can be used to predict how much bending will take place based on a knowledge of the angle of incidence and the optical density of each atmospheric level.

Absorption

• Absorption is the process by which radiant energy is absorbed and converted into other forms of energy. An absorption band is a range of wavelengths (or frequencies) in the electromagnetic spectrum within which radiant energy is absorbed by substances such as water (H

2

O), carbon dioxide

(CO

2

), oxygen (O

2

), ozone (O

3

), and nitrous oxide (N

2

O).

• The cumulative effect of the absorption by the various constituents can cause the atmosphere to close down in certain regions of the spectrum. This is bad for remote sensing because no energy is available to be sensed.

Absorption

• In certain parts of the spectrum such as the visible region (0.4 - 0.7 m), the atmosphere does not absorb all of the incident energy but transmits it effectively. Parts of the spectrum that transmit energy effectively are called “atmospheric windows”.

• Absorption occurs when energy of the same frequency as the resonant frequency of an atom or molecule is absorbed, producing an excited state . If, instead of re-radiating a photon of the same wavelength, the energy is transformed into heat motion and is reradiated at a longer wavelength, absorption occurs. When dealing with a medium like air, absorption and scattering are frequently combined into an extinction coefficient .

• Transmission is inversely related to the extinction coefficient times the thickness of the layer. Certain wavelengths of radiation are affected far more by absorption than by scattering. This is particularly true of infrared and wavelengths shorter than visible light.

Absorption of the Sun's Incident Electromagnetic Energy in the

Region from 0.1 to 30 m by Various Atmospheric Gases

Jensen, 2000

Reflectance

Reflectance is the process whereby radiation “bounces off” an object like a cloud or the terrain. Actually, the process is more complicated, involving reradiation of photons in unison by atoms or molecules in a layer one-half wavelength deep .

• Reflection exhibits fundamental characteristics that are important in remote sensing. First, the incident radiation, the reflected radiation, and a vertical to the surface from which the angles of incidence and reflection are measured all lie in the same plane. Second, the angle of incidence and the angle of reflection are equal.

Reflectance

There are various types of reflecting surfaces:

• When specular reflection occurs, the surface from which the radiation is reflected is essentially smooth (i.e. the average surface profile is several times smaller than the wavelength of radiation striking the surface).

• If the surface is rough , the reflected rays go in many directions, depending on the orientation of the smaller reflecting surfaces. This diffuse reflection does not yield a mirror image, but instead produces diffused radiation . White paper, white powders and other materials reflect visible light in this diffuse manner.

• If the surface is so rough that there are no individual reflecting surfaces, then scattering may occur. Lambert defined a perfectly diffuse surface ; hence the commonly designated Lambertian surface is one for which the radiant flux leaving the surface is constant for any angle of reflectance to the surface normal.

Reflectance

Spectral Reflectance Curves of Selected Materials

Jensen, 2000

Concept of Radiant Flux Density

Area, A

Irradiance

The concept of radiant flux density for an area on the surface of the earth. Irradiance is a measure of the amount of incoming energy in

Watts m -2 . Exitance is a measure of the amount of energy leaving in

Watts m -2 .

Area, A

Exitance

=

Concept of Radiance

Normal to Surface

Side view of Source

Area, A

The concept of radiance leaving a specific projected source area on the ground, in a specific direction, and within a specific solid angle.This is the most precise radiometric measurement used in remote sensing.

0.3

0.5

1 m 5 10 20 30 100 m

107

8

5

3

2

15 y

10 y

102

8

5

100 min

1 hr

D 1

D 2 S1

L3

S3

S2

L2

10 15 20 30

LI

106

8

5

3

2

3

2

3

2

10

8

5

3

2

5 y

4 y

3 y

2 y

1 y

180 d min

B1

T2

U2

U3

E1

L4

105

8

5

3

2

104

8

5

3

2

103

8

5

C 2

55 d

44 d

30 d

22 d

16 d

9 d

10,000 min

5 d

4 d

3 d

2 d

D E3

D E4

D E5

1 d

1,000 min

12 hr

D E2

T4

T3

1 m

D E1, E2

2

C 1

3 5

T1, U1

SPIN -2

KVR-1000 2 x 2

TK-350 10 x 10

JERS-1

MSS 18 x 24

L-band 18 x 18

SPOT HR V 1,2,3,4

Pan 10 x10

MSS 20 x 20

SPOT 5 HR G (2001; not shown)

Pan 2.5 x 2.5; 5 x 5

MSS 10 x 10; SWIR 20 x 20

ERS-1,2

C-band 30 x 30

Quickbird (2000)

0.82 x 0.82

3.28 x 3.28

EOSAT/Space Imaging

IKONOS (1999)

Pan 1 x 1

MSS 4 x 4

IRS-P5 ( 1999)

Pan 2.5 x 2.5

ORB IMAGE

OrbView 3 (1999)

Pan 1 x 1

MSS 4 x 4

OrbView 4 (2000)

Pan 1 x 1

MSS 4 x 4

H yperspectral 8 x 8 m

M5

Aerial Photography

< 0.25 x 0.25 m ( 0.82 x 0.82 ft.)

1 x 1 m (3.28 x 3.28 ft.)

R AD ARSAT

C-band

11-9, 9

25 x 28

48-30 x 28

32-25 x 28

50 x 50

22-19 x 28

63-28 x 28

100 x 100

LISS-3 23.5 x 23.5; MIR 70 x 70

LAND SAT 4,5

MSS 79 x 79

TM 30 x 30

LAND SAT 7 ETM + (1999)

Pan 15 x 15; M SS 30 x 30

TIR 60 x 60

ASTER (1999)

EOS AM -1

VNIR 15 x 15 m

SWIR 30 x 30 m

TIR 90 x 90 m

SPOT 4

Vegetation

1 x 1 km

MODIS (1999)

EOS AM -1

Land 0.25 x 0.25 km

Land 0.50 x 0.50 km

Ocean 1 x 1 km

Atmo 1 x 1 km

TIR 1 x 1 km

ORB IMAGE

OrbView 2

SeaW iFS

AVHR R

LAC 1.1 x 1.1 km

GAC 4 x 4 km

1.13 x 1.13 km

GOES

LISS-1 72.5 x 72.5

LISS-2 36.25 x 36.25

VIS 1 X 1 km

TIR 8 x 8 km

IRS-1 AB

IRS-1C D

Pan 5.8 x 5.8

Wi FS 188 x 188

METEOSAT

VISIR 2.5 x 2.5 km

TIR 5 x 5 km

M1

M2

N WS WSR -88D

D oppler R adar

1 x 1 km

4 x 4 km

M3

M4

100 m

1 km

1000 m 5 km 10 km

0.2 0.3

0.5

.8

1.0 2 3 5 10 2 3 5 102 2 3 5

Nominal Spatial Resolution in meters

103 8 104

Nominal Spatial and

Temporal Resolution of

Remote Sensor Data

Required to Extract

Urban/Suburban

Infrastructure Information

Jensen, 2000