- UVic LSS

advertisement

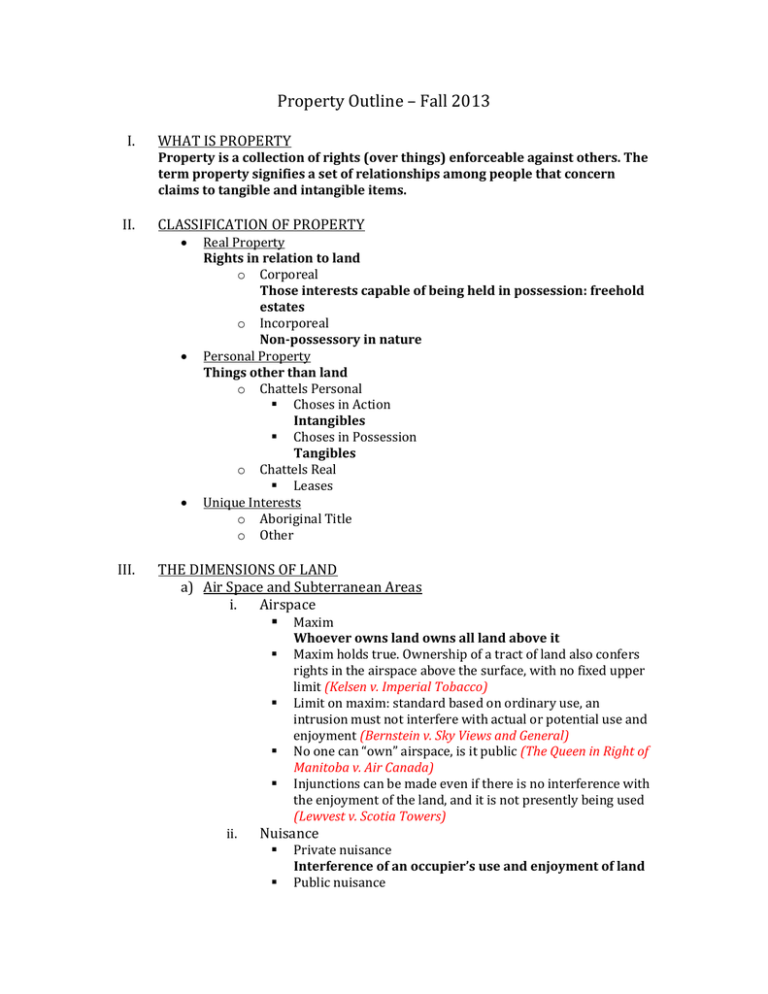

Property Outline – Fall 2013 I. II. WHAT IS PROPERTY Property is a collection of rights (over things) enforceable against others. The term property signifies a set of relationships among people that concern claims to tangible and intangible items. CLASSIFICATION OF PROPERTY III. Real Property Rights in relation to land o Corporeal Those interests capable of being held in possession: freehold estates o Incorporeal Non-possessory in nature Personal Property Things other than land o Chattels Personal Choses in Action Intangibles Choses in Possession Tangibles o Chattels Real Leases Unique Interests o Aboriginal Title o Other THE DIMENSIONS OF LAND a) Air Space and Subterranean Areas i. Airspace Maxim ii. Whoever owns land owns all land above it Maxim holds true. Ownership of a tract of land also confers rights in the airspace above the surface, with no fixed upper limit (Kelsen v. Imperial Tobacco) Limit on maxim: standard based on ordinary use, an intrusion must not interfere with actual or potential use and enjoyment (Bernstein v. Sky Views and General) No one can “own” airspace, is it public (The Queen in Right of Manitoba v. Air Canada) Injunctions can be made even if there is no interference with the enjoyment of the land, and it is not presently being used (Lewvest v. Scotia Towers) Nuisance Private nuisance Interference of an occupier’s use and enjoyment of land Public nuisance iii. Below the surface b) Fixtures Interference with public at large in exercise of rights common to all Action in nuisance can be brought if it can be proven that there has been an unreasonable interference with the enjoyment of the plaintiff’s land (Attorney General of Manitoba v. Campbell) Owner of land also has absolute subsurface rights (Edwards v. Sims) A chattel that becomes sufficiently attached to land may be transformed into a “fixture”, thereby forming part of the realty i. Tests a. The greater absorbs the smaller b. Can it have a separate existence in a useful sense c. Can it be taken apart without damage ii. Annexation In order to determine whether something is a fixture look at the degree and the object of annexation o Degree: How well fixed is it? o Object: Why was it affixed? To enhance the land or for the better use of the chattel as a chattel? Things attached to land that are easy to remove and don’t have permanency, and that for the better use of the chattel as a chattel are not fixtures (Re Davis) iii. The Fixtures Doctrine 1. Objective Test Not attached other than by own weightchattel If attached even slightlyfixture (unless appreciable damage would result from it’s removal) Can refute objective test by looking at annexation 2. Annexation Degree of annexation Object of annexation Object of annexation given more weight than degree of annexation (Recreation v. Canada Camdex Investments) iv. Contracts Whether or not a chattel becomes a fixture cannot be conclusively controlled by contract An agreement that provides that a chattel “shall not be attachment or otherwise be deemed a fixture” will not resolve the issue of characterization (Diamond Neon v. Toronto Dominion Realty) v. Items that are not attached Items not physically attached will sometimes be treated as fixtures (L&R v. Nuform) vi. Ambiguity over object of annexation As a general matter when ambiguity over the object of annexation arises because of the existence of dual functions c) Water i. ii. (chattel use and land-enhancement), attachment or nonattachment should carry the day Purpose of annexation test is hard to apply (ex: mobile homes) (Lichty v. Voigt) Categories of Water 1. Surface Water Rainwater, snowmelt 2. Water in Watercourse A defined channel either on surface of land or underground Subject to riparian rights Riparian land: land at border of land and water 3. Percolating Water Underground water that is trickling or oozing Common Law Riparian Rights o Riparian rights known as natural rights o Ordinary use: can take water in any quantity for ordinary use, such as domestic (even to the point of exhaustion) o Extraordinary use: can take water in reasonable amounts for irrigation, manufacturing, etc, as long as substantially replaced and water not significantly reduced in flow or character o Flow: downstream riparian owner entitled to a flow not substantially altered in volume or quality o Access to and from water o Accretion and drainage o o o ii. Current legislative regimes typically do not completely wash away the common law of riparian rights, unless abrogated by statute, those rights remain in force (Johnson v. Anderson) BC Water Act can nullify riparian rights (Steadman) If extracting water from different place than license gives permission, it is unlawful (Schillinger) BC Water Act Title/use of all stream water is owned by Government, unless license given or the water is unrecorded or domestic a. Definitions (s.1) Domestic Purposes: for household use, sanitation, fire prevention, domestic animals and poultry, and irrigating small gardens Groundwater: water below surface of ground Stream: natural watercourse or source of water supply, whether usually containing water or not, ground water, a lake, river, creek, spring, ravine, swamp and gulch b. c. d. e. f. g. h. iii. Percolating Water o o iv. Unrecorded Water: water the right to use of which not held under license or under a special or private Act S. 2(1): title and right to use and flow of all water in any stream in BC vested in government, except only in so far as private rights have been established under license or approvals given under this or a former Act s. 2(2): no right to divert or use water may be acquired by prescription (prescription = manner of acquiring property as a result of use/enjoyment of land openly and peacefully for a prescribed period of time) s. 3: a proclamation by LG in Canada may make this Act apply to groundwater s. 42(2): it is not an offence to divert unrecorded water (i.e. water for which no license has been issued) for domestic purposes Note this latter part makes it lawful, but does not give right, to use unrecorded water. Distinction of lawful = a shield (so I can’t be sued, can argue nuisance if someone else interferes with my use/enjoyment of my land and hence water in/on it, but do not have entitlement) from a right (i.e. entitlement) = a sword (I can sue someone else for taking it away) S. 5: licenses allow holder to divert water according to specified use, time, and quantity; to store water; construct necessary works; alter/improve stream S. 41: person commits an offence if: hinders or interferes with license holder or their works; puts sawdust, timber, tailings, gravel, refuse, etc. in stream after having been ordered not to; diverts water without authority, or more than authorized to, or that cannot use beneficially; makes changes in and about a stream without authorization. Fines are up to $200,000 per day or imprisonment not exceeding 12 months, or both S. 42(1): not an offence to divert water to extinguish a fire (but must promptly restore) Landowner can extract percolating water for any purpose, with no regard to others (Bradford) o Note: In Canada today no one has right to percolating water 1989: percolating water was not a part of Water Act and not owned by anyone, so common law principles applied (Steadman v. Erickson) o Could argue a nuisance claim Ownership of Beds of Streams, Lakes and Ponds o Ad medium filum aquae o common law presumption that the boundary of land that is adjacent to a non-tidal river extends to the o v. middle of that river, unless the documents of title state otherwise o When the body of water is tidal, ownership extends only to the ordinary or mean high water mark o Beyond that line the Crown holds title o The foreshore (the strip between the high and low marks) also belongs to the state o Tidal rivers are treated as navigable and hence reserved for general access o Ad medium will apply as a rule of construction to help assist courts and when land is sold on the border of a river even if it is not explicitly stated in the maps (Mickelthwaite) o Ad medium does still applies under BC Torrens system when land described as bounded by a nontidal and non-navigable stream (Canadian Exploration v. Rotter) Land Act o Legislation passed after Rotter to phase out ad medium rule in BC o S.55(1): no part of bed or shore is deemed to have passed to person acquiring grant unless red colour used on map, or express provision to contrary, or minister otherwise directs o S.56(2): this does not affect any claim decided by court before 1961 (so Rotter ok), or someone with indefeasible title issued before 1961 that specifically includes bed (whether or not red used) Access by Riparian Owners Riparian rights include access, right to cross foreshore, and mooring, but not the right to construct on foreshore (North Saanich v. Murray) If the waterway in it’s natural state is navigable, then it must be treated as a public highway (Welsh v. Marantette) b) Support The owner of land enjoys a right of support for land in its natural state and at its normal level, a right that must be respected by the owners of neighbouring properties o Right exists because the removal of soil on one property reduces lateral pressures imposed against adjoining lands A purchaser of land is entitled to the level of support that existed at the time the land was acquired Excavation on neighbour’s land that leads to subsidence is actionable and liability is strict A claim for loss of support is predicated on the occurrence of actual damage, not merely increasing the risk of future subsidence The right to support applies both vertically and horizontally o Ex: mining operations beneath someone’s land is actionable The natural right of support does not extend to buildings on the land If direct action of neighbor causes nature to directly or indirectly impact natural state of land, they are liable (Cleland) There is no claim if the neighbour’s actions did not have an impact on nature impacting the natural state of the land (Bremner) Natural right of support does not extend to additions or erections (Welsh) c) Accretion i. As the contours of a body of water change, so does the ii. iii. iv. v. IV. configuration of the adjoining land o Regulated by accretion, an element of common law riparian rights Accretion of the land is when there is recession of the water and the land grows, no longer belongs to the Crown but to owner of the land In order for the landowner to benefit of an accretion the process of transformation must be gradual and imperceptible in action o It is the progress of accretion that must be imperceptible, not the result o Accretion may occur through non-natural forces, as long as it is not the landowner who has caused it Accreted land cannot be foreshore, it must be dry (Neilson) Accreted land must come about by land projecting outwards horizontally (deposits must attach to adjoining land), not through vertical development (Re Bluman) BASIC PRINCIPLES OF LAND LAW a) The Doctrine of Tenure If A owns land, and dies leaving no will or no next of kin as recognized as recognized by law, the land will go to the immediate lord, which in Canada means the Crown The doctrine of tenures embodies the rules for allocating land rights and corresponding obligations, but does not describe their duration b) The Doctrine of Estates Doctrine of estates sets rules for the duration of property rights. An estate confers a segment of ownership as measured by time. There are freehold, leasehold and fee tail estates. Estates are quantitative, unlike tenures, which are qualitative. With an estate you have title to land for a period of time after which it passes to the next successive estate owner, or the Crown if there isn’t one. Technically no one owns the land, but they have an interest in the land 4 types of freehold estates 1. Fee simple Closest approximation to absolute ownership Potentially infinite duration and includes the most proprietary rights An estate that is fee simple will continue after the death of the current holder through a will or otherwise to those who are entitled under statute o If no takers an escheat will occur Proper language must be employed, or else only a life estate will be passed o “To A and his(or her) heirs” 2. Fee tail An estate in fee tail devolves only to lineal descendants Abolished in BC in 1921 3. Life Estate Estate given to someone for the duration of their life If A gives land to B, then the land returns to A upon B’s death o A is reversioner 4. Autre vie For the duration of someone else’s life Leasehold Estate An ownership of a temporary right to hold land or property in which a lessee or a tenant holds rights of real property by some form of title from a lessor or landlord. c) Equitable Interests vi. ????? d) Relationship of Real and Personal Property vii. Real Property Rights in relation to land viii. Personal Property Things other than land Personal property is allodial: you own the very thing itself, as oppose to estates which are separate from the land e) Marital Unity: Common Law and Equity f) Separate Property Regime/Claims Upon a Breakdown of Marriage V. ISSUES IN ABORIGINAL TITLE a) Introduction i. Three Competing Meanings of Aboriginal Title 1. Aboriginal Title as a mere tenancy at will Not enforceable in Canada courts Only a moral right to occupy lands Can be terminated by the sovereign Treaties that extinguish Aboriginal titles are shams because they have no legal right to the land to give it up 2. Aboriginal title as a purely personal right Aboriginal title is a legally enforceable communal interest ii. It amounts to no more than a bundle of non-exclusive rights to hunt, fish, trap and pick berries on traditional lands Rights may only be surrendered to the Crown and are not legally a right of ownership or property 3. Aboriginal title as a form of communal ownership Aboriginal title is a property right in traditional lands similar to fee simple title or ordinary land owners (protected by the law of trespass) It can only be surrendered to the Crown In most treaties surrendering your title retained their right to hunt/fish History in BC 1850-1863: Governor James Douglas makes a few treaties on Vancouver Island. Process stops leaving only a small part of BC subject to treaty 1864-1870: land policy comes under control of Trutch, and his approach is more settler-oriented 1871-1880: BC joins Canada in 1871, and jurisdiction over “lands reserved for the Indians” comes under federal power. Ottawa makes treaties through the west, and disallows land laws in BC. A year later Ottawa relents when BC agrees to the formation of a reserve commission to allot reserves. Ottawa claims BC’s land laws dealing with lands that are subject to Indian title is unconstitutional 1881-1887: A Nisga’a and Tsimshian delegation travel to Victoria in 1887 to demand a treaty. A royal commission is set up but instructed not to discuss Indian title, thus no treaty is made 1888-1905: a number of Aboriginal leaders keep putting on pressure, but immigration results in pressure to reduce reserves rather than to give Indian title. In 1899 dominion treaty No.8 extends into northern BC, but the provincial government takes no part 1906-1911: various tribes agitated to have their title recognized. Premier is unsympathetic. Legal opinion in Ottawa is that Indian title is a form of ownership and exists in BC. They want to force BC into court, but the Premier refuses. Prime Minister takes steps to force BC into court, but then loses the election 1912-1916: Nisga’a Land Committee is formed and petitions the king for a hearing before the Privy Council. Ottawa instead proposes a royal commission on Indian reserves. BC accepts as long as issue of Indian title is dropped. Commission finishes work in 1916 and the Allied Indian Tribes of BC is formed to protest Indian title 1917-1925: a decade of talks between Allied Indian and Ottawa takes place with no cooperation from BC ii. 1926-1928: Allied group gets a parliamentary hearing and BC refuses to attend. Committee rejects claim to Indian title and creates a law making it illegal to make these claims against the government. Allied tribes collapses. 1929-1950: everything put on hold due to war and Great Depression 1951-1972: ban on land claim activities is lifted in 1951 and the Nisga’a Tribal Council is established in 1955. They bring a lawsuit for Indian title, but lose at trial at the BC Court of Appeal 1973-1981: In the Calder case the SCC rules that Indian title exists in Canada, but were split 3:3 on whether the title was implicitly extinguished before BC joined Canada. Four of seven judges say they cannot decide these questions because the Nisga’a did not have BC’s permission to sue. Ottawa establishes a land claim policy allowing one claim to be brought forward at a time. BC refuses to take part and claims that there is no Indian title in BC, and that if there was, it was extinguished before BC joined Canada 1982-1984: Constitution Act recognized and affirms existing Aboriginal rights. The Gitskan and Wet’suwet’en decide to sueDelgamuukw v. The Queen 1985-1992: BC government agrees to participate in a new treaty process. The Delgammukw case grinds on. They lose at trial but BC Court of Appeal says there was no blanket extinguishment of Aboriginal rights in BC prior to confederation 1993-1997: Nisga’a agreement in principle signed in 1996, but a final agreement proves elusive. Delgammukw case goes to SCC when no treaty is negotiated. In 1997 court orders a new trial stating that Aboriginal title is a form of ownership and that BC has never had legal authority to extinguish Aboriginal title. Although the court does not actually hold they title, the implication is that a significant amount of BC is subject to unextinguished Aboriginal title. Selected Legal Precedents (Aboriginal title as a form of communal ownership) a) The Royal Proclamation of 1763 states that lands were reserved for them, and if they want to dispose of them they can do so only to the Crown b) The SCC in Canadian Pacific v. Paul said that Aboriginal title is more than the right to enjoyment and occupancy c) The SCC in Delgammukw said that Aboriginal title encompasses the right to exclusive use and occupation of the land held pursuant to that title. The Court also stated that provincial governments may not extinguish Aboriginal title and may not make laws relating to Aboriginal title or Aboriginal rights a) Delgamuukw Supreme Court clarified the basic rules for the recognition of Aboriginal title in Canadian law Boils down to first occupancy. Must be shown that land was occupied at the time of the assertion of British sovereignty Continuity between present and pre-sovereignty occupation must be shown Occupation will have been made out if it is proven that a connection with the land has been substantially maintained The occupation relied upon must have been exclusive The nature and sources of Aboriginal title Early authorities regarded Aboriginal title as a personal and usufructuary right Aboriginal title is sui generis o It is unique and no particular rule of property law applies to it Unique features of Aboriginal title o It is inalienable except to the Crown o Title is held communally by the members of an Aboriginal nation o Aboriginal title also differs from other kinds of holdings by virtue of its source: it pre-dates the assertion of colonial sovereignty o The right to the exclusive use and occupation of the affected lands lie within the bundle of rights conferred by this kind of title o Use of land is not limited by traditional practices that are integral to the Aboriginal society However, the use to which the land is put must be consistent with the nature of the group’s historic attachment to the land b) R v. Marshall Aboriginal rights, some of which are analogous to profits a prendre, can also be recognized under the common law or by way of treaty c) Cultural Property/Traditional Knowledge