Gender and CHD: a social science perspective - Dr David

advertisement

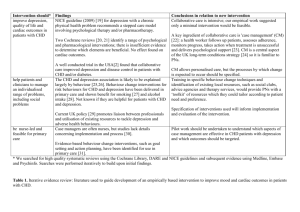

BACR & IACR Welcomes you Annual Conference Belfast 2006 Belfast 2006 GENDER AND CHD: A SOCIAL SCIENCE PERSPECTIVE David G. Shaw dshaw02@bcuc.ac.uk TERMINOLOGY SEX: a biological term used by physical scientists… • genetic constitution, hormones, secondary sexual characteristics • essentially immutable • femaleness and maleness GENDER: a psycho-social term used by social scientists… • expression of biological sex • behaviour, emotions, communication, etc • learned and therefore culture-bound • masculinity and femininity GENDER DIFFERENCES IN HEALTH WOMEN MEN more sick leave/days in bed more health/medical consultations more self-medication more reproductive problems more chronic illness serious chronic diseases more acute non-fatal illnesses acute fatal illnesses neurotic disorders pathological grief, PTSD depression burnout higher levels of physical symptoms better self-rated health old age infirmity higher all-cause mortality SUMMARY differences in morbidity (women are sicker than men) differences in mortality (men die earlier than women) applies broadly to industrialised societies but almost all this is changing CHD MORTALITY BY SEX (BHF 2005, ICD codes 120-125) number of percentage of CHD deaths all CHD deaths females 51 495 45.2% males 62 400 54.8% total 113 895 100% percentage of all deaths female 16% male 22% CHD: A MAN’S DISEASE Images of CHD:"....not the delicate, neurotic person......but the vigorous in mind and body, the keen and ambitious man, the indicator of whose engine is always at full speed ahead.“ (Osler, 1892) Type A Personality/Behaviour Pattern (Rosenman & Freidman, 1974) • competitive, hard-driving, impatient, aggressive etc • a metaphor for masculinity The persistent stereotype of a coronary candidate is likely to be a middle aged, middle class man, red-faced, overweight, excitable, overworked, and in a high powered job. Women were ignored in cardiac research for many years leading to a very weak evidence base for practice. Some awakening through the 1990’s but a number of studies have mixed findings…why? THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SEX AND GENDER GENDER SEX (biological characteristi (gendered roles, social norms, attitudes etc) EXPLAINING GENDER DIFFERENCES BIOLOGICAL • genetics • hormones • immune response • stress reaction BEHAVIOURAL • health knowledge • health behaviour: eg smoking; food choices; exercise • illness behaviour • service uptake • communication PSYCHO-SOCIAL (good reviews by Brezinka & Kittel, 1996; Jacobs & Stone, 1999) Socio-Economic Status (Wilkinson, Marmot) • usually defined as poverty and low educational attainment • a stronger determinant of CHD mortality in women than men • difference persists when health behaviours are factored out • single status • we need to ask why? Emotions & Support • anxiety and depression are more common among women • sources of stress likely to be different for many women eg marital stress is more important to women than work stress (OrthoGomer et al 2000) • social relationships are not a proxy for social support (Chesney & Darbes 1998) social support needs to be reconceptualised to take into account the obligations and care-giving aspects EMPLOYMENT (good chapter in Orth-Gomer et al, 1998) In general, having a job is associated with good health in both sexes. However… • in men the impact of work on health is likely to be a function of the work demands only • in women it is likely to be the work demands combined with other areas of demand • the stress threshold above which work strain might have a detrimental effect is lower for women • work is more cardio-protective for managerial/professional women • women in paid work tend to occupy different jobs to men Karasek & Theorell’s Demand-Control Model: • high job demands; low autonomy/decision latitude; and low social support • pathogenic job profile associated with CHD and other illnesses DEMAND-CONTROL MODEL (Morrison & Bennett 2006, after Karasek & Theorell) high decision control dentist sales person architect scientist police officer bank manager physician school teacher low demand high demand night watchman janitor lorry driver carpenter low decision control telephonist cook waiter secretary STEREOTYPICAL FEMALE CORONARY CANDIDATE (after Jacobs & Stone, 1999) • • • • • • • • • • post-menopausal and with co-morbidities low SES with little formal education high perceived stress homemaker with no outside job or has high demand-low control and still does most of the home tasks low social support in and out of the home widow, also impacted by other bereavements negative health behaviours (smoker, high fat diet, lack of exercise) of South Asian origin lay care-giver But do such women see themselves as coronary candidates? COMPONENTS OF TREATMENT DELAY INTERVAL patient delay onset of symptoms to point of contact with EMS EMS delay contact with EMS to arrival in hospital arrival in hospital to start of treatment hospital delay total delay period onset of symptoms to start of treatment ILLNESS BEHAVIOUR… The ‘gender paradox’ - women delay even longer than men. • possibly different presentation, context of background of comorbid symptoms, low somatic awareness • competing time and role demands, role adherence • concerns about troubling others • structural barriers, eg transport, health insurance (US) Cardiac illness prototypes are culturally shared beliefs about CHD. • social construction of ‘standard’ cardiac symptoms based on male norms • low public perception of risk compared with carcinoma of breast • applies to HPs as well as members of the public SELF-REGULATORY MODEL (Leventhal & Cameron, 1987) REPRESENTATION OF PROBLEM ACTION PLAN FOR COPING WITH PROBLEM APPRAISAL EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE ACTION PLAN FOR COPING WITH EMOTION APPRAISAL INTERNAL & ENVIRONMENTAL STIMULI …ILLNESS BEHAVIOUR Self-Regulatory Model focuses on the individual: • cognitive representations – sets of beliefs about CHD (risk, causes, presentation, seriousness etc) • pervasive fallacies about low susceptibility (even in the face of multiple risk factors) • women are often indecisive in the face of symptoms • often make inappropriate lay or professional consultations • beliefs about symptoms might not match experience, which correlates( with delays Heuristics (decision-rules) correlate with delays: • one is that we tend to attribute symptoms to stress when they occur in challenging circumstances • another is gender, which will influences attribution (Martin & Suls, 2003) DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT Women more commonly misdiagnosed: • ECG changes less prominent in women • symptoms might be different • but HPs are no different to anyone else; their perceptions are subject to error (eg McKinlay studies) • medical textbooks – disproportionate number of male images Investigation and treatment: Numerous UK and US studies have shown that women are less likely: • to be admitted to CCU, and to be thrombolysed • to receive aspirin and ß blockers on discharge • to be offered angioplasty or CABG (much debate about the possible reasons for all this) CR ATTENDANCE Another paradox… • women are less likely to attend and complete CR • especially low those from low SES groups; MEG’s; elders; & younger women less likely (Inverse Care Law) • women are less likely to be invited Emery (1995) identifies three areas to consider in encouraging women to attend:1. Programme characteristics 2. The CR environment 3. Patient characteristics Other factors: women are less likely to be accompanied; more likely to need social support from the group; role adherence for both sexes, though roles might differ. REHABILITATION AND THE SICK ROLE Role Resumption: • many women resume activities too soon, sooner than men • and the activities are often inadvisable • additive effect of various roles • salience of place, those for whom the home is also the workplace • role attraction Several recent UK studies: Thornton, Radley, Shaw. Work disability: • data on women are scarce but there are a couple of good studies • less likely to be encouraged to return to work by HPs • might have different motives for returning to work: men are more likely to return to work if married and if high income; in women no relationship with income, singles more likely to return • women see themselves as tougher and rate their MI as less severe, so they soldier on (Nau et al 2005) EMOTIONALITY • • • • • • • • • females more anxious and depressed than males but this applies to trait anxiety and depression pre-CHD anyway so correlational studies are of little help some of the difference might result from reporting bias due to social norms about emotional expression and females generally prefer to use emotion-focussed coping styles in some studies depression emerged later in men (after a month), which could be due to the resumption of roles and diminution of denial, which is more common in men women often have to face their problems earlier than men, and therefore become distressed earlier women are consistently more prone to vicarious distress less likely to have the benefit of protective buffering from partner SEXUAL MORBIDITY • many studies on male coronary victims • a number of small studies and a couple of big ones on post MI women – results are equivocal • but there are significant problems in both sexes • difficult to unpack, given the unknown dyadic dynamics • women are older, more anxious and might have older husbands • direction of causality yet to be established CAUSAL ATTRIBUTIONS Most studies have been on men, but some data on women (eg Lewin et al): • men tend to attribute their CHD to modifiable causes (eg smoking, diet) • women tend to make external attributions (ag luck, fate, heredity) • this external locus of control might help explain women’s non-uptake of CR since the things on offer will do little to assist with their perceived cause • might also explain why women are less likely to modify risky behaviour Stress is an attribution common to both but the source might be different: • in men it is often work stress • women often identify relationship/family problems (eg bereavement) and care-giving roles IMPLICATIONS • explain about the nature of CR rather than just invite • need to be aware that women generally are at higher risk of psycho-social impairment than men • women are not a homogeneous group • need to examine sub-components of gender and other individual variables such as culture • assess and work with causal attributions • assess role occupancy and tailor CR accordingly • assess social support and maximise where possible • more research on women’s illness representations • government/public health policy needs to focus superordinate social factors that lead to individual behaviour BACR & IACR Welcomes you Annual Conference Belfast 2006