Industrial Revolution - Tamalpais Union High School District

advertisement

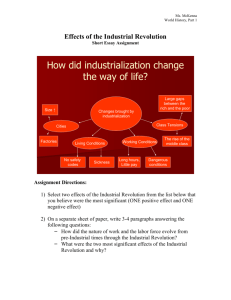

Industrial Revolution Issues and Responses Urban Conditions As the new towns and cities rapidly developed during the Industrial Revolution the need for cheap housing, near the factories, increased. Whilst there were some men, such as Robert Owen, who were willing to create good housing for their workers, many employers were not. These employers ruthlessly exploited their workers by erecting poor, and often unsanitary, shoddily built houses. Workers often paid high rents for, at best, sub-standard housing. In the rush to build houses, many were constructed too quickly in terraced rows. Some of these houses had just a small yard at the rear where an outside toilet was placed. Others were ‘back to back’ with communal toilets. Almost as soon as they were occupied, many of these houses became slums. Most of the poorest people lived in overcrowded and inadequate housing, and some of these people lived in cellars. It has been recorded that, in one instance, 17 people from different families lived in an area of 5 metres by 4 metres. Sanitary arrangements were often non-existent, and many toilets were of the ‘earth closet’ variety. These were found outside the houses, as far away as possible because of the smell. Usually they were emptied by the ‘soil men’ at night. These men took the solid human waste away. However, in poorer districts, the solid waste was just heaped in a large pile close to the houses. The liquid from the toilets and the waste heaps seeped down into the earth and contaminated the water supplies. These liquids carried disease-causing germs into the water. The most frightening disease of all was cholera. The streets where the poor lived were poorly kept. A doctor in Manchester wrote about the city: "Whole streets, unpaved and without drains or main sewers, are worn into deep ruts and holes in which water constantly stagnates, and are so covered with refuse and excrement as to be impassable from depth of mud and intolerable stench." Fresh water supplies were also very difficult to get in the poor areas. With no running water supplies, the best people could hope for was to leave a bucket out and collect rainwater. Some areas were lucky enough to have access to a well with a pump but there was always the chance that the well water could have been contaminated with sewage from a leaking cesspit. Those who lived near a river could use river water. However, this is where nightmen emptied their carts full of sewage and where general rubbish was dumped. Any water collected would have been diluted sewage. Life in Industrial Towns The Industrial Revolution witnessed a huge growth in the size of British cities. In 1695, the population of Britain was estimated to be 5.5 million. By 1801, the year of the first census, it was 9.3 million and by 1841, 15.9 million. This represents a 60% growth rate in just 40 years. Manchester, as an example, experienced a six-times increase in its population between 1771 and 1831. Bradford grew by 50% every ten years between 1811 and 1851 and by 1851 only 50% of the population of Bradford was actually born there. None of these homes was built with a bathroom, toilet or running water. You either washed in a tin bath in the home with the water being collected from a local pump or you simply did not wash. Many didn’t wash as it was simply easier. There would be a courtyard between each row of terraces. Waste of all sorts from the homes was thrown into the courtyard and so-called night-men would collect this at night and dispose of it. Sanitation and hygiene barely existed and throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the great fear was a cholera, typhus or typhoid epidemic. Toilets would have been nothing more than cesspits. When these were filled they had to be emptied and what was collected was loaded onto a cart before being dumped in a local river. This work was also done by the night-men. Local laws stated that their work had to be done at night as the stench created by emptying the cesspits was too great to be tolerated during the day. When the great social reformer Lord Shaftesbury visited one house, he went into the cellar – where a family was living – and found that the sewage from a nearby cesspit had leaked right under their floor boards. A block of 40 houses would have possibly 6 toilets for all persons. It is estimated that on average 9 people lived in one house, which would mean that 6 toilets served 360 people! Another problem was that it was the responsibility of the landlord of the house to pay to have cesspits emptied and they were never too enthusiastic to do this. One cesspit cost £1 to empty. As the average rent was 2 shillings a week, this equalled 5 weeks rent. No-one in local authority enforced the law In the first half of the 19th century, urban overcrowding, poor diets, poor sanitation, and essentially medieval medical remedies all contributed to very poor public health for the majority of English people. The densely packed and poorly constructed working-class neighborhoods contributed to the fast spread of disease. As we read in Engels’ first hand account of working-class areas in Manchester, these neighborhoods were filthy, unplanned, and slipshod. Roads were muddy and lacked sidewalks. Houses were built touching each other, leaving no room for ventilation. Perhaps most importantly, homes lacked toilets and sewage systems, and as a result, drinking water sources, such as wells, were frequently contaminated with disease.Cholera, tuberculosis, typhus, typhoid, and influenza ravaged through new industrial towns, especially in poor working-class neighborhoods. In 1849, 10,000 people died of cholera in three months in London alone ("Public Health Timeline"). Tuberculosis claimed 60,000 to 70,000 lives in each decade of the 19th century (Robinson). Poor nutrition, disease, lack of sanitation, and harmful medical care in these urban areas had a devastating effect on the average life expectancy of British people in the first half of the 19th century. The Registrar General reported in 1841 that the average life expectancy in rural areas of England was 45 years of age but was only 37 in London and an alarming 26 in Liverpool (Haley). These are life-long averages that highlight a very high infant mortality rate; in the first half of the 19th century, 25 to 33% of children in England died before their 5th birthday (Haley). Perhaps the most dramatic example of a scientific breakthrough occurred at a drinking well in London in 1854. A physician, John Snow, traced an epidemic outbreak of cholera back to a specific well in the Soho neighborhood of central London. Snow applied the scientific method to the situation and hypothesized that cholera spread through the use of tainted water. So he made a detailed map showing where victims lived in the area:clustered around a single contaminated well. The dot map showed that greater distance from the well meant fewer incidents of plague. This cholera map provided conclusive proof of how the disease spread (it was later discovered that the well had been dug just two feet from an old sewage pit). The epidemic subsided soon after the city disabled the pump. Snow also demonstrated that households getting water from downstream pumps—infected by nearby sewers—suffered a death rate fourteen times greater than those that pulled water from upstream pumps. As a simple public health solution, Snow recommended boiling water before use. Snow’s investigations and experiments led the way to improved public health and hygiene in the new densely packed urban areas (Haley). The British government addressed public health by passing regulatory laws to curb the ills of workingclass urban living. The Public Health Act of 1848 set up local health boards, investigated sanitary conditions nationwide, and established a General Board of Health. The local boards had the responsibility of ensuring that water supplies were safe. And in the 1875 Public Health Act, the government took on more responsibility for public health, adding housing, sewage, drainage, and contagious diseases. This Each new law was a big step forward for modern medicine and public health, and a far cry from the medieval bloodletting that had occurred only decades earlier (Haley). What were the working conditions like during the Industrial Revolution? Well, for starters, the working class—who made up 80% of society—had little or no bargaining power with their new employers. Since population was increasing in Great Britain at the same time that landowners were enclosing common village lands, people from the countryside flocked to the towns and the new factories to get work. This resulted in a very high unemployment rate for workers in the first phases of the Industrial Revolution. Henry Mayhew, name his title or role, studied the London poor in 1823, and he observed that “there is barely sufficient work for the regular employment of half of our labourers, so that only 1,500,000 are fully and constantly employed, while 1,500,000 more are employed only half their time, and the remaining 1,500,000 wholly unemployed” (Thompson 250). As a result, the new factory owners could set the terms of work because there were far more unskilled laborers, who had few skills and would take any job, than there were jobs for them. Also, since the textile industries were so new at the end of the 18th century, there were initially no laws to regulate them. Desperate for work, the migrants to the new industrial towns had no bargaining power to demand higher wages, fairer work hours, or better working conditions. Worse still, since only wealthy people in Great Britain were eligible to vote, workers could not use the democratic political system to fight for rights and reforms. In 1799 and 1800, the British Parliament passed the Combination Acts, which made it illegal for workers to unionize, or combine, as a group to ask for better working conditions. For the first generation of workers—from the 1790s to the 1840s—working conditions were very tough, and sometimes tragic. Most laborers worked 10 to 14 hours a day, six days a week, with no paid vacation or holidays. Each industry had safety hazards too; the process of purifying iron, for example, demanded that workers toiled amidst temperatures as high as 130 degrees in the coolest part of the ironworks (Rosen 155). Under such dangerous conditions, accidents on the job occurred regularly. A report commissioned by the British House of Commons in 1832 commented that "there are factories, no means few in number, nor confined to the smaller mills, in which serious accidents are continually occurring, and in which, notwithstanding, dangerous parts of the machinery are allowed to remain unfenced" (Sadler). The report added that workers were often "abandoned from the moment that an accident occurs; their wages are stopped, no medical attendance is provided, and whatever the extent of the injury, no compensation is afforded" (Sadler). As the Sadler report shows, injured workers would typically lose their jobs and also receive no financial compensation for their injury to pay for much needed health care. “Chant no more your old rhymes about bold Robin Hood His feats I but little admire I will sing the achievements of General Ludd, Now the Hero of Nottinghamshire” (547). The Luddites The most dramatic uprising against the negative effects of the Industrial Revolution in Britain began around what was left of the deforested Sherwood Forest, Nottinghamshire, the land of the fabled Robin Hood. The rebels were skilled weavers and other pre-industrial artisans who saw in the new textile machines the destruction of their traditional craft, their livelihood, and their community. In 1811, when the uprising began, about half the families in the Nottingham region were unable to support themselves and were reduced to Poor Law charity (Sale 66). And because the government had passed laws making it illegal for workers to meet, form a union, or go on strike, this desperate group met covertly and swore secret oaths of allegiance to each other. These rebellious artisans wrote anonymous letters to factory owners warning them to close down or face the consequences. Then they raided factories at night and destroyed the new textile machines that took away their jobs. Neither the sheriff of Nottingham nor the new factory owners knew precisely who the secret members were. But the rebels signed their first letter of demands, “From Robin Hood’s Cave” (3). These rebellious and skilled artisans became known as the “Luddites” (pronounced “LUHD-eyets”). Since the organization was so secret—after all, swearing an oath of obedience to the group was a crime in itself—there remain today no surviving documents or testimonies that clarify for certain the origin of the name. Some evidence suggests the name is derived from an old children’s story about a child, Ned Ludd, who broke his knitting frame in anger to spite his father. Some historians suggest the name refers to the Celtic God, Lludd. Still others find evidence of an ancient King Lud who ruled over a city that later came to be called “Ludon” or “London” (78). In any case, the group often signed its letters as “King Lud” or “Ned Ludd.” So, the group became known as the Luddites. A small movement of writers and philanthropists responded to the negative effects of the Industrial Revolution by designing and trying to implement new ideal, or utopian, communities. But some utopian communities sought to create cooperative industrial environments in response to what they viewed as individualistic, competitive, and exploitive capitalist societies. They dreamed of communities that focused on creating more dignified working conditions and better treatment of women and children. Some radical utopians focused on socialism—an economic system (about which you will learn more in the next section) that focuses on cooperation and equality amongst all economic classes in society. One of the most well-known utopian socialists was a factory owner named Robert Owen (1771-1858). He wrote about and tried to put into practice utopian factory communities in which workers were treated fairly and encouraged to reach their potential (“Robert Owen”). Inside Robert Owen’s Factory In 1799, after making his fortune managing textile factories in Manchester, Owen bought the only four cotton mills in a small town in Scotland called New Lanark (“Robert Owen”). He then began experimenting with putting into practice his utopian dream of a cooperative industrial town. Concerned with the welfare of his workers, he went to great expense to ensure they had education, houses of their own, and access to doctors. Owen focused especially on education and children. He disallowed physical punishment of young people, common in these times as a form of discipline. Children under ten years of age could not work in his factories and had to attend a school that he had built. Owen also created, in 1816, the first known nursery of the industrial era for children under age six; as a result, mothers could go back to work six months to a year after childbirth. Owen also ensured that the factories, streets, and community buildings were clean and well tended (“Biography of Robert Owen”). Despite all the expenses that Owen incurred to improve the welfare of the workers, New Lanark succeeded commercially. The utopian community became famous throughout Europe because it showed that factories could treat families with dignity, improve working conditions, and still make a profit. The British Parliament set up a commission in 1832 to investigate child labor in factories. Based on those findings, Parliament felt compelled to respond. As a result, the government passed The Factory Act of 1833 to regulate excessive child labor. The act set limits on how many hours per day children could work. This was the first ever government regulation of the industrial workplace. It was a very small step: even after the reform, nineyear-old children, for example, could still work nine hours a day, six days a week. Factory owners had resisted the law because they said it would slow down production, increase the cost of their products, and make them less competitive. And, some parents of the child workers worried that their families would have less money to survive as a result of the lost income. Nonetheless, this first child labor law set a new precedent: that the British Parliament might reluctantly take it upon itself to regulate abuses in the industrial workplace. The key provisions of the Factory Act of 1833: ● Children 8 and younger could not work in factories. ● Employers had to have an age certificate for their child workers. ● Children between 9-13 years could work no more than 9 hours a day. ● Children between 13-18 years could work no more than 12 hours a day. ● Children could not work at night. ● Four factory inspectors were appointed to investigate thousands of factories throughout England and enforce the law (“1833 Factory Acts”). The Romantic Movement developed in the United Kingdom in the wake of, and in some measure as a response to, the Industrial Revolution. Many English intellectuals and artists in the early 19th century considered industrialism inhumane and unnatural and revolted—sometimes quite violently—against what they felt to be the increasingly inhumane and unnatural mechanization of modern life. Poets such as Lord Byron (particular in his addresses to the House of Lords) and William Blake (most notably in his poem “The Chimney Sweeper”) spoke out—and wrote extensively about—the psychological and social affects of the newly industrial world upon the individual and felt rampant industrialization to be entirely counter to the human spirit and intrinsic rights of men. Many English Romantic intellectuals and artists felt that the modern industrial world was harsh and deadening to the senses and spirit and called for a return, both in life and in spirit, to the emotional and natural, as well as the ideals of the pre-industrial past. In 1834 a new Poor Law was introduced. Some people welcomed it because they believed it would: ● reduce the cost of looking after the poor ● take beggars off the streets ● encourage poor people to work hard to support themselves The new Poor Law ensured that the poor were housed in workhouses, clothed and fed. Children who entered the workhouse would receive some schooling. In return for this care, all workhouse paupers would have to work for several hours each day. Except in special circumstances, poor people could now only get help if they were prepared to leave their homes and go into a workhouse. Conditions inside the workhouse were deliberately harsh, so that only those who desperately needed help would ask for it. Families were split up and housed in different parts of the workhouse. The poor were made to wear a uniform and the diet was monotonous. There were also strict rules and regulations to follow. Inmates, male and female, young and old were made to work Chartism The dissent and insubordination of the English workingmen reached its peak in the mid- nineteenth century with Chartism, an ideology that called for political reform in the country. Its name was based on the People's Charter, a document written in 1838 by William Lovett and other radicals of the London Working Men's Association, and adopted at a national convention of workingmen's organizations in August of that year. The Charter called for several changes to the Parliamentary system: o Universal Male Suffrage o Annual Parliaments o Vote by ballot o Abolition of the property qualification for MPs o Payment of MPs o Equal electoral constituencies (Chartism too much talk, too little action) Flora Tristan: French writer and political activist, The Worker’s Union, 1843 Workers, you must leave behind division and isolation as quickly as possible and march courageously and fraternally down the only appropriate path- unity...The workers, the vital part of the nation, must create a huge union to assert their unity! Then, the working class will be strong; then it will be able to make itself heard, to demand from the bourgeois gentlemen its right to work and organize. Workers, it is up to you, who are the victims of real inequality and injustice, to establish the rule of justice and absolute equality between man and woman on this earth...You, the strong men, the men with bare arms, proclaim your recognition that woman is your equal, and as such, you recognize her equal right to the benefits of the universal union of working men and women. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, German Social Theorists, The German Ideology 1845-1846 The alteration of men on a mass is necessary, an alteration which can only take place in a practical movement, a revolution; this revolution is necessary, therefore, not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew. Louis Blanc, French political leader, The Organization of Labor, introduction to the second edition, 1848. Have we avowed that our goal is to undermine competition, to withdraw industry from the regime of laissez-faire? Most certainly, and far from denying it, we proclaim it aloud. Why? Because we want freedom. But real freedom, freedom for all...We want a strong government because, in the regime of inequality within which we are still vegetating, there are weak persons who need a social force to protect them...We want a government that will intervene in industry because the freedom of the future must be a reality.