TARIKI TRUST PSYCHOTHERAPY TRAINING PROGRAMME

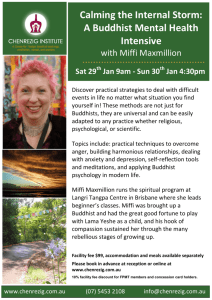

advertisement