Reassessing Middlebrow Drama during the Second World War

advertisement

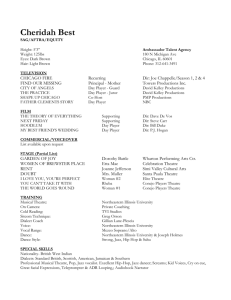

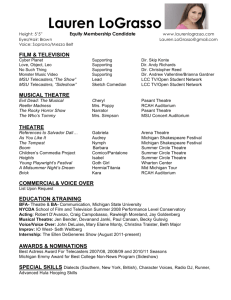

Reassessing Middlebrow Drama during the Second World War Dr Rebecca D’Monté, University of the West of England, Bristol Above: Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, London (stalls and circle the morning after bomb damage, 1940) Left: Argyle Theatre, Birkenhead (auditorium after bomb damage in 1940) Right: Hippodrome Theatre, Dover (Second World War bomb damage) Above: Streatham Hill Theatre, London (V1 rocket bomb damage, 1944) Entertainments National Services Association (ENSA) Left: John Gielgud takes a production overseas in an ENSA plane Above: The Western Brothers in North Africa Left: ENSA Programme Middlebrow writers are important in expressing ‘ideas and modes of feeling which were commonplace among the intelligentsia before the war’ but they have ‘a suggestive insensitiveness to the life round them, a lack of discrimination and the functioning of a second-rate mind.’ Q. D. Leavis (1932) Fiction and the Reading Public. London: Pimlico. ‘The Middlebrow is the man, or woman, of middlebred intelligence who ambles and saunters now on this side of the hedge, now on that, in pursuit of no single object, neither art nor life itself, but both mixed indistinguishably, and rather nastily, with money, fame, power, or prestige.’ Virginia Woolf (1942) 'Middlebrow'. In The Death of the Moth. London: Hogarth Press. ‘the common terms “highbrow”, “lowbrow” and “middlebrow” created a convenient aesthetic and psychological equivalent to the British class system, labelling authors and readers in one epigrammatic blow.’ Clive Bloom (2002) Bestsellers: Popular Fiction Since 1900, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ‘This is a war of the unknown warriors….The whole of the warring nations are engaged, not only soldiers, but the entire population, men, women and children. The fronts are everywhere. The trenches are dug in the towns and streets. Every village is fortified. Every road is barred. The front lines run through the factories. The workmen are soldiers with different weapons but the same courage.’ Winston Churchill, quoted in Angus Calder (1969) The People’s War: Britain 1939-1945. London: Pimlico, p. 17. Above: Miniature of Manderley Above and Left: Judith Anderson and Joan Fontaine, in Rebecca (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1940) Above: Celia Johnson, with Trevor Howard, Brief Encounter (dir. David Lean, 1945) Right: Robert Newton & Celia Johnson, This Happy Breed (dir. David Lean, 1944) Above and Right: Owen Nares, Matinee Idol J. B. Priestley at the BBC Right and Below Right: Film of Quiet Weekend (dir. Harold French, 1947) Location: East Garston, Berkshire Above: Quiet Week-End, Esther McCracken (1938; revived in 1941 with Michael Wilding and Glynis Johns) u Above: Dear Octopus, Dodie Smith (Queen’s Theatre, dir. Glen Byam-Shaw, 1938, with Marie Tempest and John Gielgud) Above: Film of This Happy Breed (dir. David Lean, 1944; with Robert Newton, Celia Johnson, and Stanley Holloway) This royal throne of kings, this scepter’d isle, This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars, This other Eden, demi-paradise. This fortress built by Nature for herself Against infection and the hand of war, This happy breed of men, this little world, This precious stone set in the silver sea, Which serves it in the office of a wall Or as a moat defensive to a house, Against the envy of less happier lands,— This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England. William Shakespeare, Richard II, 2.1 Left: Mrs Miniver (dir. William Wyler, 1942; with Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon) Above: No Medals, Esther McCracken (Vaudeville Theatre, dir. Richard Bird, 1944; l. to r. Pauline Tennant, Fay Compton, Valerie White) ‘Miss Esther McCracken. Writes the kind of domestic comedy that is always safe because it touches everyday experience and does not botch its details. No Medals is about the cares of a housewife in wartime (and, for that matter, in time of peace). It is about marmalade and vacuum-cleaners and charwomen and plum-bottling and fish-queues…audiences accept it as part of the theatre ritual, continue to chuckle at the domesticities familiar in their mouths as household words, and leave, restored, to return to their own fish-queues, and vacuum-cleaners, and marmalade.’ J. C. Trewin, ‘Women as Playwrights’, John O’London’s Weekly, November 2, 1945. The Years Between, Daphne du Maurier, Wyndham’s Theatre, 1945 Left: Film (dir. Compton Bennett, 1946; with Valerie Hobson and Michael Redgrave) Right: Play revived at the Orange Tree Theatre, Richmond, 2007 (dir. Caroline Smith, with Karen Ascoe and Michael Lumsden)