HERE - Bekemeyer's World

advertisement

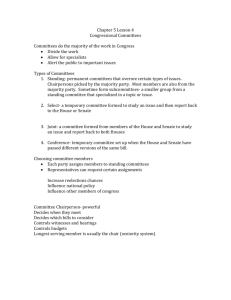

American Government Mr. Bekemeyer Comparison: U.S. House and U.S. Senate Why We Have a House and Senate Driven by Their Differences By Robert Longley Why do we have two chambers in Congress, the House and Senate? Since members of both are elected by, and represent the people, wouldn't the lawmaking process be more efficient if bills were considered by only one body? While it may appear clumsy and often overly time-consuming, the two-chamber or "bicameral" setup of Congress works today exactly the way a majority of the Founding Fathers envisioned in 1787. Clearly expressed in the Constitution is the Founders' belief that power should be shared among all units of government. Dividing Congress into two chambers, with the positive vote of both required to approve legislation, is a natural extension of the Founders' concept of employing "checks and balances" to prevent tyranny. The Founding Fathers explain the formation of Congress to the people in the Federalist Papers 52-66. Why are the House and Senate so Different? Have you ever noticed that major bills are often debated and voted on by the House in a single day, while the Senate's deliberations on the same bill take weeks? Again, this reflects the Founding Fathers' intent that the House and Senate not be carbon-copies of each other. By designing differences into the House and Senate, the Founders assured that all legislation would be carefully considered, taking both the short and long-term effects into account. Why are the Differences Important? The Founders intended that the House be seen as more closely representing the will of the people than the Senate. To this end, they provided that members of the House - U.S. Representatives - be elected by and represent limited groups of citizens living in small geographically defined districts within each state. Senators, on the other hand, are elected by and represent all voters of their state. When the House considers a bill, individual members tend to base their votes primarily on how the bill might impact the people of their local district, while Senators tend to consider how the bill would impact the nation as a whole. This is just as the Founders intended. All members of the House are up for election every two years. In effect, they are always running for election. This insures that members will maintain close personal contact with their local constituents, thus remaining constantly aware of their opinions and needs, and better able to act as their advocates in Washington. Elected for six-year terms, Senators remain somewhat more insulated from the people, thus less likely to be tempted to vote according to the short-term passions of public opinion. By setting the constitutionally-required minimum age for Senators at 30, as opposed to 25 for members of the House, the Founders hoped Senators would be more likely to consider the long-term effects of legislation and practice a more mature, thoughtful and deeply deliberative approach in their deliberations. Setting aside the validity of this "maturity" factor, the Senate undeniably does take longer to consider bills, often brings up points not considered by the House and just as often votes down bills passed easily by the House. A famous (though perhaps fictional) simile often quoted to point out the differences between the House and Senate involves an argument between George Washington, who favored having two chambers of Congress and Thomas Jefferson, who believed a second chamber to be unnecessary. The story goes that the two Founders were arguing the issue while drinking coffee. Suddenly, Washington asked Jefferson, "Why did you pour that coffee into your saucer?" "To cool it," replied Jefferson. "Even so," said Washington, "we pour legislation into the senatorial saucer to cool it." 2 Leadership Structure of the U.S. Congress (adapted from Lowi, et al., American Government and Barbour, et al., Keeping the Republic) The majority and minority in each house elect their own leaders, who are, in turn, the leaders of Congress. The Constitution provides for the election of some specific congressional officers, but Congress itself determines how much power the leaders of each chamber will have. The main leadership offices in the House of Representatives are the Speaker of the House (the only post established by the Constitution), the majority leaders, the minority leader, and the whips. The real political choice about who the party leader should be occurs within the party groupings or caucuses in each chamber. The Speaker of the House is elected by the majority party Speaker of the House John Boehner (R-OH) and, as the person who presides over debates on the floor of the House, is the most powerful House member. The House majority leader, second in command, is given wide-ranging responsibilities to assist the Speaker. The House minority leader is the official head of the minority party in the House. In the House of Representatives, the Speaker of the House and the majority leader work together to organize the chamber and set the legislative agenda. The Speaker and the majority leader have great influence in the process of determining which members are seated in the different committees and subcommittees. They also have some sway over determining the powerful position of chair of each committee, although the traditional seniority system gives strong preference to members of the majority party who have been sitting in the committee the longest. The Speaker and the majority leader also help determine the course of legislation in the chamber. For example, when a bill is initially dropped in the hopper as a legislative proposal, the Speaker of the House determines which committee has jurisdiction over it. Since the mid-1970s, the Speaker has had multiple-referral power, permitting him or her to assign different parts of a bill to different committees or the same parts sequentially or simultaneously to several different 3 committees. The Speaker can also influence the scheduling of legislation, a factor that can be crucial to a bill’s success, even pulling a bill from consideration when defeat would embarrass the chamber’s leadership. The Speaker is also second in the line of succession to the presidency after the Vice President under the Presidential Succession Act of 1947. The leadership organization in the Senate is similar but not as elaborate. According to the Constitution, the presiding officer of the Senate is the vice president of the United States, who can cast a tie-breaking vote when necessary but otherwise does not vote or take part in debates and does not sit in any committee. When the vice president is not present, which is almost always the case, the president pro tempore of the Senate officially presides. This role is given to the majority party member with the greatest seniority. Because of the Senate’s much freer rules for deliberation on the floor, the presiding officer has less power than in the House, where debate is generally tightly controlled by the Speaker. The locus of real leadership in the Senate is the Senate majority leader and the Senate minority leader. Although the smaller and highly individualistic Senate would not accept the kind of formal authority afforded the Speaker of the House, like the Speaker, the Senate majority leader can influence the scheduling of bills and can withdraw a bill from consideration. In both chambers, Democratic and Republican leaders are assisted by party whips. (The term whip comes from an old English hunting expression; the “whipper in” was charged with keeping dogs together in pursuit of the fox.) Elected by party members, whips find out how people intend to vote so that on important party bills, the leaders can adjust legislation, negotiate acceptable changes, or employ favors (or, occasionally, threats) to line up support. Whips work to persuade party members to support the party on key bills, and they are active in making sure favorable members are available to vote when needed. The Committee System (adapted from Lowi, et al., American Government and Barbour, et al., Keeping the Republic) Meeting as full bodies, it would be impossible for the House and the Senate to consider and deliberate on all of the 100,000 bills and 100,000 nominations they receive every two years. Hence, the work is broken up and handled by smaller groups called committees. The Constitution says nothing about congressional 4 committees; they are completely creatures of the chambers of Congress they serve. But they are, indeed, the only way that the legislative process can function in an efficient manner in the House and, to a lesser extent, in the Senate, where chaos would ensue were all matters to be addressed by the general membership. It is at the committee and, even more, the subcommittee stage that the nittygritty details of legislation are worked out – and where members of Congress – who in committees act as specialists in an area of legislation – have the most opportunity to influence the outcome of the process. Committees act as the eyes, ears, and workhorses of Congress in considering, drafting, and redrafting proposed legislation. Congress has four types of committees: standing, select, joint and conference. The vast majority of work is done by the standing committees. These are permanent committees, created by law, that carry over from one session of Congress to the next. Standing committees are said to have gate-keeping authority. They review most pieces of legislation that are introduced to Congress. After a bill is sent to a committee, the committee may take no further action on it, amend the legislation in any way, or even write its own legislation before bringing the bill before the whole chamber for a vote. Committees, then, are lords of their jurisdictional domains, setting the table, so to speak, for their parent chamber. So powerful are the standing committees, in sum, that they scrutinize, hold hearings on, amend, and, frequently, kill legislation before the full Congress ever gets the chance to discuss it. The size of the standing committees and the ratio of majority to minority party members on each are determined at the start of each Congress by the majority leadership in the House and by negotiations between the majority and minority leaders in the Senate. Standing committee membership is relatively stable as seniority on the committee is a major factor in gaining subcommittee or committee chair; the chairs wield considerable power and are coveted positions. When a problem before Congress does not fall into the jurisdiction of a standing committee, a select committee may be appointed. These committees are usually temporary and do not recommend legislation but are, rather, used to gather information on specific issues. An example of a select committee was the Select 5 Committee on Homeland Security that conducted investigations following the September 11 terror attacks. Joint committees are made up of members of both houses of Congress. There are currently only four joint committees. They are the joint committees on the library, on printing, on taxation, and the joint economic committee. None of the joint committees have legislative powers, limiting themselves to conducting researching issues and monitoring the activities of the parts of the executive branch. Before a bill can become a law, it must be passed by both houses of Congress in exactly the same form. But because the legislative process in each house often subjects bills to different pressures, they may be very different by the time they are debated and passed. Conference committees are temporary committees made up of members of both houses of Congress commissioned to resolve these differences, after which the bills go back to each house for a final vote. 6 U.S. House Standing Committees (Source: U.S. House Website) U.S. Senate Standing Committees (Source: U.S. Senate Website) Committee on Agriculture Committee on Appropriations Committee on Armed Services Committee on the Budget Committee on Education and Labor Committee on Energy and Commerce Committee on Financial Services Committee on Foreign Affairs Committee on Homeland Security Committee on House Administration Committee on the Judiciary Committee on Natural Resources Committee on Oversight and Government Reform Committee on Rules Committee on Science and Technology Committee on Small Business Committee on Standards of Official Conduct Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure Committee on Veterans' Affairs Committee on Ways and Means 7 Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry Appropriations Armed Services Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs Budget Commerce, Science, and Transportation Energy and Natural Resources Environment and Public Works Finance Foreign Relations Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Judiciary Rules and Administration Small Business and Entrepreneurship Veterans' Affairs Members of the U.S. House Committee on Agriculture, 113th Congress (Source: U.S. House Website) 8 9 10 11 12 Members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry (Source: U.S. Senate Website) 13 14 Constituency Demographics The United States Ethnicity 65.9% White Non-Hispanic, 15.1% Hispanic, 12.4% Black, 4.3% Asian Distribution 82% urban, 12% rural Median Income $49,445 Poverty Rate 15.1% 2008 Election 52.10% Barack Obama (Dem.), 45.7% John McCain (Rep.) State of Georgia – Sen. Saxby Chambliss (R-GA) and Sen. Johnny Isakson (R-GA) Population 9,829,211 Ethnicity 57.5% White Non-Hispanic, 30.2% Black, 8.3% Hispanic, 3.0% Asian Median Income $44,696 Poverty Rate 16.9% Distribution 81% urban 18% rural 2008 Election 52.10% McCain, 46.90% Obama 49.8% Sen. Chambliss (Rep.), 46.8% Martin (Dem.) Georgia’s 6th Congressional District – Rep. Tom Price (R-GA) Population 629,725 Ethnicity 74.2% White 8.9% Black 8.7% Hispanic 6.3% Asian Distribution 96.69% urban 2.31% rural Median Income $82,593 Poverty Rate 3.9% 2008 Election 64.7% McCain 68% Rep. Price 15 Georgia’s 5th Congressional District – John Lewis (D-GA) Population 629,727 Ethnicity 50.2% Black 37.6% White 8.1% Hispanic 2.6% Asian Distribution 99.54% urban 0.46% rural Median Income $50,072 Poverty Rate 15.2% 2008 Election 78.9% Obama 100% Rep. Lewis Georgia’s 9th Congressional District – Tom Graves (R-GA) Population 629,672 Ethnicity 81.3% White 3.4% Black 12.8% Hispanic 1.3% Asian Distribution 33.8% urban 66.12% rural Median Income $49,065 Poverty Rate 10% 2010 election 80.1% McCain 100% Rep. Graves State of New York – Sen. Charles Schumer (D-NY) and Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) Population 19,541,453 Ethnicity 59.9% White Non-Hispanic, 17.2% Black, 16.8% Hispanic, 7.1% Asian Median Income $46,320 Poverty rate 13.7% Distribution 92.2% urban 7.8% rural 2008 Election Obama 62%, McCain 37% 2006 Election 68% Sen. Clinton (Dem.) 16 2010 Election 63% Kirsten Gillibrand (Dem.) New York’s 15th Congressional District – Charlie Rangel (D-NY) Population 654,360 Ethnicity 45.1% Hispanic 27.6% Black 21.3% White 3.7% Asian Distribution 100% urban Median Income $37,240 Poverty Rate 22.6% 2008 Election 87.9% Obama 89% Rep. Rangel New York’s 26th Congressional District – Christopher Lee (R-NY) Population 654,360 Ethnicity 90.2% White 3.5% Black 2.5% Hispanic 2.2% Asian Distribution 71.17% urban 28.8% rural Median Income $55,576 Poverty Rate 6% 2008 Election 51.7% McCain 55% Rep. Lee 17 Party Voting in Congress, 1970-2006 (Source: Barbour, et al., Keeping the Republic) Ideological Distance Between the Two Major Parties in the U.S. Congress, 18792011 (Source: Voteview.com) 18