UF Poster Template - Department of Pharmaceutical Outcomes

advertisement

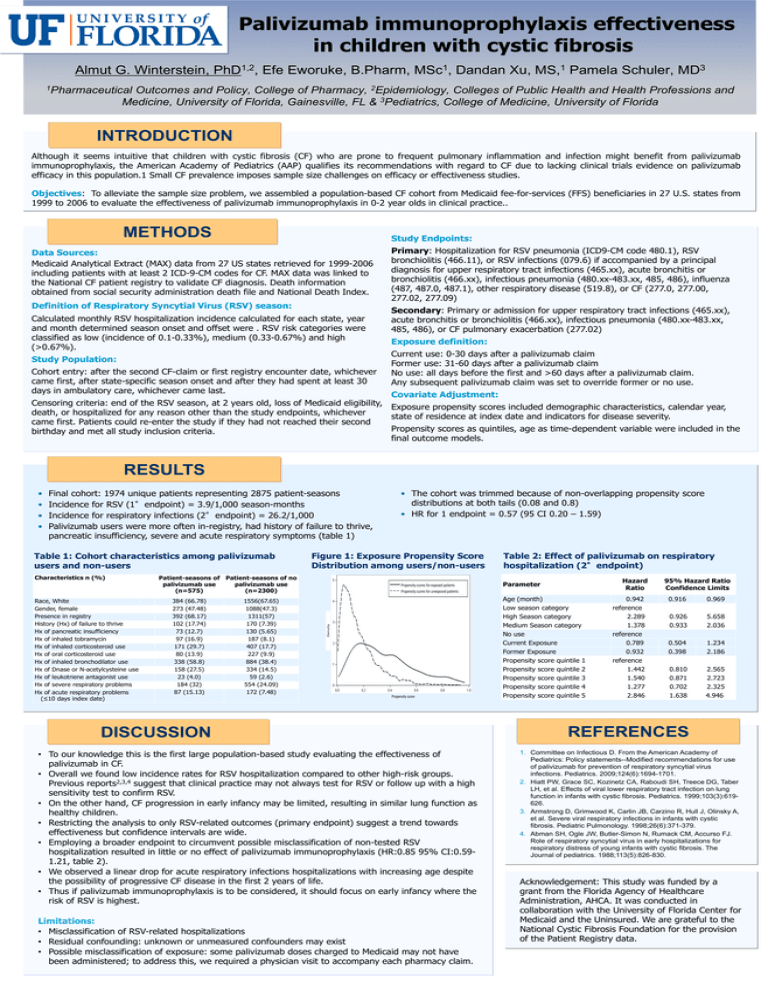

Palivizumab immunoprophylaxis effectiveness in children with cystic fibrosis Almut G. Winterstein, 1,2 PhD , Efe Eworuke, B.Pharm, 1 MSc , Dandan Xu, 1 MS, Pamela Schuler, 3 MD 1Pharmaceutical Outcomes and Policy, College of Pharmacy, 2Epidemiology, Colleges of Public Health and Health Professions and Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL & 3Pediatrics, College of Medicine, University of Florida INTRODUCTION Although it seems intuitive that children with cystic fibrosis (CF) who are prone to frequent pulmonary inflammation and infection might benefit from palivizumab immunoprophylaxis, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) qualifies its recommendations with regard to CF due to lacking clinical trials evidence on palivizumab efficacy in this population.1 Small CF prevalence imposes sample size challenges on efficacy or effectiveness studies. Objectives: To alleviate the sample size problem, we assembled a population-based CF cohort from Medicaid fee-for-services (FFS) beneficiaries in 27 U.S. states from 1999 to 2006 to evaluate the effectiveness of palivizumab immunoprophylaxis in 0-2 year olds in clinical practice.. METHODS Study Endpoints: Data Sources: Medicaid Analytical Extract (MAX) data from 27 US states retrieved for 1999-2006 including patients with at least 2 ICD-9-CM codes for CF. MAX data was linked to the National CF patient registry to validate CF diagnosis. Death information obtained from social security administration death file and National Death Index. Definition of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) season: Calculated monthly RSV hospitalization incidence calculated for each state, year and month determined season onset and offset were . RSV risk categories were classified as low (incidence of 0.1-0.33%), medium (0.33-0.67%) and high (>0.67%). Study Population: Cohort entry: after the second CF-claim or first registry encounter date, whichever came first, after state-specific season onset and after they had spent at least 30 days in ambulatory care, whichever came last. Primary: Hospitalization for RSV pneumonia (ICD9-CM code 480.1), RSV bronchiolitis (466.11), or RSV infections (079.6) if accompanied by a principal diagnosis for upper respiratory tract infections (465.xx), acute bronchitis or bronchiolitis (466.xx), infectious pneumonia (480.xx-483.xx, 485, 486), influenza (487, 487.0, 487.1), other respiratory disease (519.8), or CF (277.0, 277.00, 277.02, 277.09) Secondary: Primary or admission for upper respiratory tract infections (465.xx), acute bronchitis or bronchiolitis (466.xx), infectious pneumonia (480.xx-483.xx, 485, 486), or CF pulmonary exacerbation (277.02) Exposure definition: Current use: 0-30 days after a palivizumab claim Former use: 31-60 days after a palivizumab claim No use: all days before the first and >60 days after a palivizumab claim. Any subsequent palivizumab claim was set to override former or no use. Covariate Adjustment: Censoring criteria: end of the RSV season, at 2 years old, loss of Medicaid eligibility, Exposure propensity scores included demographic characteristics, calendar year, death, or hospitalized for any reason other than the study endpoints, whichever state of residence at index date and indicators for disease severity. came first. Patients could re-enter the study if they had not reached their second Propensity scores as quintiles, age as time-dependent variable were included in the birthday and met all study inclusion criteria. final outcome models. RESULTS Final cohort: 1974 unique patients representing 2875 patient-seasons Incidence for RSV (1°endpoint) = 3.9/1,000 season-months Incidence for respiratory infections (2°endpoint) = 26.2/1,000 Palivizumab users were more often in-registry, had history of failure to thrive, pancreatic insufficiency, severe and acute respiratory symptoms (table 1) Table 1: Cohort characteristics among palivizumab users and non-users Characteristics n (%) Race, White Gender, female Presence in registry History (Hx) of failure to thrive Hx of pancreatic insufficiency Hx of inhaled tobramycin Hx of inhaled corticosteroid use Hx of oral corticosteroid use Hx of inhaled bronchodilator use Hx of Dnase or N-acetylcysteine use Hx of leukotriene antagonist use Hx of severe respiratory problems Hx of acute respiratory problems (≤10 days index date) Figure 1: Exposure Propensity Score Distribution among users/non-users Patient-seasons of Patient-seasons of no palivizumab use palivizumab use (n=575) (n=2300) 384 (66.78) 273 (47.48) 392 (68.17) 102 (17.74) 73 (12.7) 97 (16.9) 171 (29.7) 80 (13.9) 338 (58.8) 158 (27.5) 23 (4.0) 184 (32) 87 (15.13) 1556(67.65) 1088(47.3) 1311(57) 170 (7.39) 130 (5.65) 187 (8.1) 407 (17.7) 227 (9.9) 884 (38.4) 334 (14.5) 59 (2.6) 554 (24.09) 172 (7.48) • The cohort was trimmed because of non-overlapping propensity score distributions at both tails (0.08 and 0.8) • HR for 1 endpoint = 0.57 (95 CI 0.20 – 1.59) Propensity scores for exposed patients Propensity scores for unexposed patients Density • • • • Propensity score DISCUSSION • To our knowledge this is the first large population-based study evaluating the effectiveness of palivizumab in CF. • Overall we found low incidence rates for RSV hospitalization compared to other high-risk groups. Previous reports2,3,4 suggest that clinical practice may not always test for RSV or follow up with a high sensitivity test to confirm RSV. • On the other hand, CF progression in early infancy may be limited, resulting in similar lung function as healthy children. • Restricting the analysis to only RSV-related outcomes (primary endpoint) suggest a trend towards effectiveness but confidence intervals are wide. • Employing a broader endpoint to circumvent possible misclassification of non-tested RSV hospitalization resulted in little or no effect of palivizumab immunoprophylaxis (HR:0.85 95% CI:0.591.21, table 2). • We observed a linear drop for acute respiratory infections hospitalizations with increasing age despite the possibility of progressive CF disease in the first 2 years of life. • Thus if palivizumab immunoprophylaxis is to be considered, it should focus on early infancy where the risk of RSV is highest. Limitations: • Misclassification of RSV-related hospitalizations • Residual confounding: unknown or unmeasured confounders may exist • Possible misclassification of exposure: some palivizumab doses charged to Medicaid may not have been administered; to address this, we required a physician visit to accompany each pharmacy claim. Table 2: Effect of palivizumab on respiratory hospitalization (2°endpoint) Hazard Ratio Parameter Age (month) Low season category High Season category Medium Season category No use Current Exposure Former Exposure Propensity score quintile 1 Propensity score quintile 2 Propensity score quintile 3 Propensity score quintile 4 Propensity score quintile 5 0.942 reference 2.289 1.378 reference 0.789 0.932 reference 1.442 1.540 1.277 2.846 95% Hazard Ratio Confidence Limits 0.916 0.969 0.926 0.933 5.658 2.036 0.504 0.398 1.234 2.186 0.810 0.871 0.702 1.638 2.565 2.723 2.325 4.946 REFERENCES 1. Committee on Infectious D. From the American Academy of Pediatrics: Policy statements--Modified recommendations for use of palivizumab for prevention of respiratory syncytial virus infections. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1694-1701. 2. Hiatt PW, Grace SC, Kozinetz CA, Raboudi SH, Treece DG, Taber LH, et al. Effects of viral lower respiratory tract infection on lung function in infants with cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 1999;103(3):619626. 3. Armstrong D, Grimwood K, Carlin JB, Carzino R, Hull J, Olinsky A, et al. Severe viral respiratory infections in infants with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology. 1998;26(6):371-379. 4. Abman SH, Ogle JW, Butler-Simon N, Rumack CM, Accurso FJ. Role of respiratory syncytial virus in early hospitalizations for respiratory distress of young infants with cystic fibrosis. The Journal of pediatrics. 1988;113(5):826-830. Acknowledgement: This study was funded by a grant from the Florida Agency of Healthcare Administration, AHCA. It was conducted in collaboration with the University of Florida Center for Medicaid and the Uninsured. We are grateful to the National Cystic Fibrosis Foundation for the provision of the Patient Registry data.