Killing Non-Human Animals I: Peter Singer

advertisement

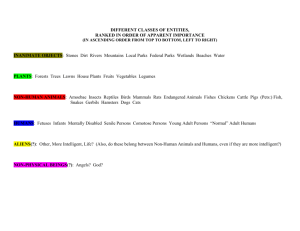

1 Is it Wrong to Kill Non-Human Animals? I 2 Peter Singer: “All Animals are Equal ” Singer’s Project • Singer argues we should “extend to other species the basic principle of equality that most of us recognize should be extended to members of our own species.” (401) • As such, we need to curtail the use of animals in experiments (medical or otherwise). • As well, if we are going to eat meat, we need to minimize the suffering of animals in the food industry. 3 Singer’s Central Argument P1 Beings have interests just in case they are capable of suffering. (404) P2 Human beings and many non-human animals are capable of suffering. P3 Therefore, human beings and many non-human animals have interests. P4 Basic Principle of Equality: “[T]he interests of every being […] are to be taken into account and given the same weight as the interests of any other being.” (403) P5 Human beings and many non-human animals have an interest in avoiding suffering. C Therefore, the interests non-human animals have in avoiding suffering is to be given the same weight as the interests human beings have in avoiding suffering. 4 Equality & Discrimination • A liberation movement demands an expansion of our moral horizons and an extension or reinterpretation of the “basic moral principle of equality”. Race Orientation Sex • Practices previously regarded as natural and inevitable come to be seen as being based on an unjustifiable prejudice. • We should make the same mental switch in our attitudes and practices towards non-human animals, extending to other species the same principle of equality that we recognize should be extended to members of our own species. 5 Wollstonecroft & Taylor • Mary Wollstonecraft’s 1792 book, Vindication of the Rights of Women, was widely regarded as absurd. • Thomas Taylor responds with an anonymous satire, A Vindication of the Rights of Brutes, in which he tries to show that the arguments supplied by Wollstonecraft, if sound, are equally sound when applied to non-human animals. But, Taylor argues, that “brutes” have equal rights to men is patently absurd. If the argument leading to the conclusion that non-human animals have rights equal to men is unsound, then so too is Wollstonecraft’s argument, since the same argument is used in each case. 6 Capacities & Rights • Might we respond to Taylor, that the reason women have an equal right to men, but that non-human animals do not, is that women and men have certain capacities that non-human animals do not, such as the ability to make rational decisions? In other words, men and women are similar and so should have equal rights, while humans and nonhumans are different and so should not have equal rights. • Certainly, biologically, men and women have different capacities, and these may lead to different rights. Likewise, since a pig isn’t capable of voting, it shouldn’t have the right to vote. 7 Equality Does Not Imply Sameness • “The extension of the basic principle of equality from one group to another does not imply that we must treat both groups in exactly the same way, or grant exactly the same rights to both groups.” (401) • Rather, the sort of equality we should be concerned with is equality of consideration, and equal consideration for different beings may lead to different treatments and different rights. • Certainly, humans come in all sorts of sizes and shapes, with differing moral capacities, intellectual abilities, sensitivities, capacities to experience pain and pleasure, and so on. If the demand for equality were based on some actual equality of all human beings, we would have to stop demanding equality. 8 Equality Does Not Imply Sameness • “Although humans differ as individuals in various ways, there are no differences between the races and sexes as such.” (402) A person’s race or sex is no guide to his or her abilities. • So far as actual abilities are concerned, there do seem to be some measurable differences between races and sexes, when taken on average. What we don’t know is how much of this difference is due to genetic endowments, and how much to environmental differences. But it would be dangerous to rest a case against racism and sexism on the belief that all significant differences are environmental in origin: if there did turn out to be some genetic basis for differences in ability, racism and sexism would in some way be defensible. 9 Equality Does Not Imply Sameness • There is a stronger argument to be made for equality for the races and sexes – one which does not depend upon intelligence, moral capacity, physical strength, or other matters of fact. Equality is a moral ideal and not a simple assertion of fact. There is no compelling reason for assuming any factual difference in ability between two people justifies any difference in the amount of consideration we give to satisfying their needs and interests. The principle of the equality of human beings is not descriptive of their actual equality, but prescriptive of how we should treat them. 10 Equal Consideration of Interests • To treat another being as equal to another means to give both beings equal consideration for their interests. • “The capacity for suffering and enjoying things is a prerequisite for having interests at all, a condition that must be satisfied before we can speak of interests in a meaningful way.” (404) I can suffer, so I I can’t suffer, so I can have interests. can’t have interests. 11 Suffering, Sentience, and Speciesism • If a being can suffer, there can be no justification for not taking that suffering into consideration. “No matter what the nature of the being, the principle of equality requires that its suffering be counted equally with the like suffering—in so far as rough comparisons can be made—of any other being.” (404) Sentience—the capacity to suffer or experience enjoyment—is the only defensible boundary of concern for the interests of others. • Racism violates the principle of equality by giving greater weight to the interests of members of one’s own race. • Likewise, speciesism violates the principle of equality by giving greater weight to the interests of members of one’s own species. • “Most human beings are speciesists.” (404) 12 Suffering, Sentience, and Speciesism • We tend to regard the lives of non-human animals as a means to an end: we eat them. • But we don’t need to eat animals, certainly not on the grounds of satisfying nutritional needs. • An even clearer indication of our speciesism is the suffering we inflict on non-human animals while they are alive before we eat them. • None of these practices cater to any more than our tastes. • “To avoid speciesism we must stop this practice, and each of us has a moral obligation to cease supporting this practice.” (405) 13 Non-Human Experimentation • The same form of discrimination is apparent in the widespread practice of experimentation on other species to ascertain if some substances are safe for human beings, or what effect some stimulus will have. If an experimenter is not prepared to experiment on a newborn infant, he should likewise refrain from experimenting on adult non-human mammals. If anything, adult non-human mammals are more aware, and is at least as sensitive to pain as a newborn infant. Certainly, we should be more prepared to experiment on brain-dead human beings than healthy, adult non-human animals. • The experimenter shows his speciesism by experimenting on a non-human animal where he would not perform the same experiment on a human at an equal or lower level of sentience. 14 Non-Human Experimentation • If humans are to be regarded as equal to one another, then we need some sense of “equal” that does not require any actual equality of capacities, talents, or other factual characteristics. • If, on the other hand, we are to regard “all humans are equal” as a non-factual (perhaps prescriptive) statement, it is even more difficult to exclude non-humans from the sphere of equality. 15 Singer’s Central Argument Revisited P1 Beings have interests just in case they are capable of suffering. (404) P2 Human beings and many non-human animals are capable of suffering. P3 Therefore, human beings and many non-human animals have interests. P4 Basic Principle of Equality: “[T]he interests of every being […] are to be taken into account and given the same weight as the interests of any other being.” (403) P5 Human beings and many non-human animals have an interest in avoiding suffering. C Therefore, the interests non-human animals have in avoiding suffering is to be given the same weight as the interests human beings have in avoiding suffering. 16 Singer’s Central Argument Revisited P1 Beings have interests just in case they are capable of suffering. Might a being have interests and yet be incapable of suffering? P2 Human beings and many non-human animals are capable of suffering. Certainly, there are borderline cases, but certainly this clearly applies to dogs, and cats, and cows, and chickens, and… P3 Therefore, human beings and many non-human animals have interests. Follows from P1 and P2. 17 Singer’s Central Argument Revisited P4 Basic Principle of Equality: “[T]he interests of every being […] are to be taken into account and given the same weight as the interests of any other being.” There are multiple ways that the Basic Principle might be violated: racism, sexism, speciesism... According to Singer’s argument, humans in persistent vegetative states do not have interests, and so the Basic Principle does not apply to them. P5 Human beings and many non-human animals have an interest in avoiding suffering. Implicit in the above argument. C Therefore, the interests non-human animals have in avoiding suffering is to be given the same weight as the interests human beings have in avoiding suffering.