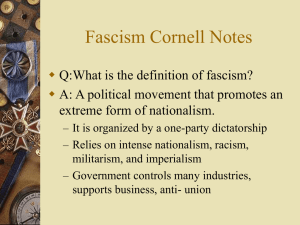

The Relationship between Fascism and Nationalism

advertisement

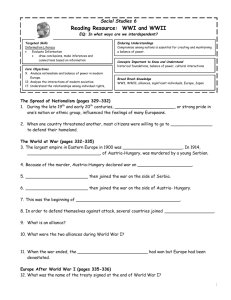

The Relationship between Fascism and Nationalism It is evident why fascism could be considered to be an extreme form of nationalism –many fascist regimes have been most particularly characterized by their extreme nationalistic feelings, for example the Nazi emphasis on the importance of being German. It could be argued that some of the beliefs that characterize fascism are simply extensions of nationalistic ideas. For example the positive focus on struggle and competition could be seen to be the logical conclusion to the idea that ones nation is superior to other nations as victory in struggle proves that this is so. Furthermore the two ideologies also share certain beliefs, such as the idea of organic society. However such ideological similarities do not mean that fascism can be regarded simply as nationalism at its most extreme, the central themes of fascism and the way these have been put into practice demonstrate that this is not the case. The most convincing evidence that fascism is simply an extreme form of nationalism comes from the fact that fascists are supporters of nationalism. They emphasize the importance of the unity of the nation. In Italian and Spanish fascism this was promoted through the idea of loyalty to the state, Mussolini regularly reiterated the philosophy of Giovanni Gentile, “everything for the state, nothing against the state, nothing outside the state”. Meanwhile German fascism (Nazism) took a different approach to nationalism, focusing on cultural and racial unity of the people, for example portraying Aryan Germans as the ‘master race’. Like nationalism, fascism can be seen to promote unity through a shared culture and history, for example under the Nazis children were taught about the heroic deeds of the Teutonic knights in the Middle Ages. It can be seen that this idea of shared culture is more extreme in fascism than other forms of nationalism, particularly in Italian fascism where the popular idea that Italy in the past a glorious established single nation was actually largely a crafted myth. This suggests that fascism is more than an extreme form of nationalism as cultural nationalists do not create a false history to promote their own ideas, but merely emphasize aspects of culture that are in existence, for example in Scotland there are celebrations of haggis and bagpipe playing. However, whilst nationalism is celebratory of cultural differences fascism can be seen to be far more destructive. This is particularly evident in Nazi Germany where differences were not just frowned upon but destroyed with the use of extermination camps. Furthermore the fascist idea is far more than simple patriotism and valuing of tradition, it stresses the idea of a ‘national re-birth’, for example in Italy the emphasis was on modernization and industrialization, which again separates the fascism that occurred there from nationalism. The fact that this was more evident in Italy than Germany suggests that Nazism was a more nationalistic form of fascism (although both exhibited fascist elements). Nazism contained more of the elements of traditional nationalism, for example emphasizing common aspects of culture and race, whereas Italian fascism is more economically based. The Nazi approach is far more extreme than traditional nationalism, for example the persecution of Jews simply because of their racial identity. Whilst the basic ideas of cultural separation in Nazism can be regarded as nationalistic, the extremity of such fascist action marks it as ideologically separate to nationalism, rather than a strong extension of it, it is racialism rather than just extreme nationalism. Since Nazism is evidently the most nationalistic form of fascism this suggests that nationalism is not merely an extreme form of nationalism. However what ultimately separates the nationalistic aspect of fascism from nationalism itself is its aggressive militant aspect. Nationalism is partly characterized by the concept of self-determination, each state has the right to exist and to decide how it is governed. This idea is clearly overlooked in fascist thinking and there is a clear expansionist element. This was evident in the 1930s when Japan occupied Manchuria, Italy began to found an African empire through invasion of Abyssinia and Germany sought ‘lebensraum’ (living space) by first taking over Austria and later invading Czechoslovakia and Poland. Whilst nationalists may argue that it can be necessary to defend the nation, pursuing such expansion without just cause could not be defended from a nationalist viewpoint and is hence clearly unique to fascism. The two ideologies may appear to have similarities but they have completely different foundations for their beliefs – nationalists believe in national pride whereas fascists believe in national superiority. The difference is evident in the way fascist countries have acted. Therefore whilst nationalist beliefs are a part of fascist ideology, most particularly Nazism, fascism is not just an extreme form of nationalism. Fascist nationalism is markedly different to nationalism itself as an ideology and some forms of fascism do not even exhibit nationalism as their most overpowering force. Ultimately fascism has more components than simply being extreme nationalism, hence why it is classed as a separate ideology. A central theme of fascism that emphasizes this difference from nationalism is the positive view of struggle. This demonstrates the militant nature of fascism; it is the adaptation of Darwin’s theory of evolution in a way to fit human beings – ‘social Darwinism’. The belief is that human existence is based on competition and so progress comes from conflict, which means war is good and it is important to have regular conflict to maintain strength, which is valued extremely highly. This is evident in fascist regimes, for example both Germany and Italy in the 1930s introduced compulsory military service and were more than prepared to go to war in 1945, seeing war as the ultimate test of strength. Mussolini exhibited the view that war is good and natural when he said “war is to men what maternity is to women”. Whilst strength is valued in fascist thought naturally its opposite, weakness, is despised, as was evident in Germany where there were attempts to eliminate disability (which was perceived as weakness) by forcibly sterilizing the mentally and physically disabled. Nationalism has no such focus on the idea of strength, nor does it value war in itself, usually regarding it as appropriate only as a defense strategy, for example as a way to gain independence. Therefore the idea of struggle suggests that fascism is not merely an extreme form of nationalism, as nationalists do not show support for war, they believe the nation as it is to be a good thing, but they do not believe in forced strength. This is clearly a key ideological difference. One central belief of fascists that differentiates them from nationalists is idea of leadership and elitism. This was based on the philosophy of Nietzsche who spoke of an ‘ubermensch’ (superman) who was a gifted and powerful individual. Fascists emphasize the necessity of an unquestioned all-powerful leader who they believe to reflect the will of the people. This has been evident in all fascist regimes, for example Hitler in Germany, Mussolini in Italy and Franco in Spain. Beneath the leader there is a small elite, for example the SS in Germany, to help carry out the leader’s work, beneath them are the ordinary people and beneath them the underclass (who are not a real part of society). Such a defined social system is not evident in nationalism, indeed in most forms of nationalism it is simply being part of a nation that allows you to be part of the belief system. Whilst it could be argued that both fascism and nationalism believe in the collective good of the nation, which makes them appear similar, in nationalism there is no belief in an unquestioned leader to ‘embody’ such this collective good. This is an evident ideological difference, as the idea of a strong leader and complete opposition to democracy is a central feature in fascism, whereas nationalism can occur in a variety of political systems, including democratic ones, for example America and Wales. Fascists can also be characterized by their opposition to rationalism and the ideas that dominated liberal political philosophy. They believe in the ideas of Friedrick Nietzsche, that humans are driven by emotion not by reason. This was a complete contrast to enlightenment thinkers such as Immanuel Kant, who believed that humans should act on reason alone. However fascists see ‘normal’ political life as ‘cold, dry and lifeless’ and believe that (in the words of Henry Bergson) living creatures have a life force that must be expressed. This emphasis on emotion can be seen to have occurred in fascist regimes, for example in Nazi Germany Hitler was famous for his hugely passionate speeches that appealed strongly to the emotions of the people. This is an evidently similar approach to that of nationalism, which is also filled with emotion such as pride and love for one’s country. This is apparent in the passion evident in nationalist groups, for example Indian nationalists were willing to go on hunger strike and long marches in order to try to gain independence. The strength of emotion in Enoch Powell’s famous ‘rivers of blood’ speech could be seen to be merely a less extreme form of the anti-rationalism evident in Hitler’s famous addresses. However it is not the case that fascism simply takes the emotional approach of nationalism one step further. Fascists actively oppose the idea of rationalism in a way that nationalists do not. Nationalists may be emotional regarding their ideas but they do not specifically reject the idea of using reason, indeed liberal nationalists would argue that their ideas are a product of reason. This difference makes it evident that fascism is indeed more than an extreme form of nationalism, it is a separate ideology with a different belief system. One notable feature of fascism is that in some ways it has been considered similar to socialism, for example it is anti-capitalist, values the community above the individual, is against materialism and believes that leadership should be based on personality not financial power. These ideas were evident in fascist regimes, for example in both Germany and Italy there were attempts to control big business and focus on the collective good, Nazi coins were inscribed with the slogan ‘common good before private good”. It could potentially be argued that nationalism also has similarities to socialism, for example nationalists focus on the good of the nation over the good of the individual and nationalist aims, such as independence or cultural recognition are often not material. However these similarities do not in any sense show that fascism is nothing more than an extreme form of nationalism, it merely demonstrates that there are ideological overlaps between fascism, nationalism and socialism (indeed nationalism has occurred in both fascist and socialist regimes). In conclusion fascism certainly is something more than an extreme form of nationalism. Whilst fascist regimes, particularly Nazi Germany, demonstrate a strong belief in nationalism, the extremity of actions demonstrates a different belief, a belief in racialism. Furthermore fascism is characterized by other key beliefs which are not shared by nationalists, such as struggle and leadership and elitism. These can be seen to be even more fundamental to fascism that nationalistic beliefs as different kinds of fascist regimes place different emphasis on nationalism, whereas leadership and struggle remain ideologically central regardless of the strand of fascism in question. The central themes of fascism and the ways they have been manifested in different countries indicates that whilst fascism may have some similarities to nationalism ultimately it is ideologically distinct.