rafiqui record keeping - bflo

advertisement

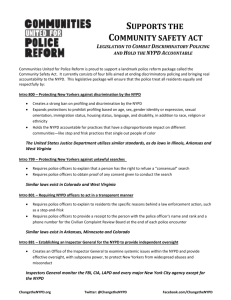

Record Keeping And Public Access By The Buffalo Police Department At Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority Properties: By Ammad W. Rafiqi QUESTIONS PRESENTED: 1. What records does BPD keep of its interactions with BMHA residents, visitors, trespassers, etc.? Furthermore, what types of information are recorded and how are the records available to the public? 2. What are best practices from around the country in record keeping and public access? RECORD KEEPING AND PUBLIC ACCESS: Upon talking to Rebecca Town, a public defender at the Legal Aid Bureau of Buffalo and contacting the Buffalo Police Department (BPD) Records office; it appears that the police are not required to fill in (and do not) any It appears that the police are not required to fill in (and do not) any forms upon the initiation or termination of their encounters with civilians. With the exception of arrest records, no information is accessible to lawyers or the public for review forms upon the initiation or termination of their encounters with civilians. With the exception of arrest records, no information is accessible to lawyers or the public for review. This stands in contrast with civilian encounter forms completed by the Boston Police Department (Boston PD) and the New York Police Department (NYPD) (enacted postTerry decision1). The only data available is misdemeanor arrests data from the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, which is grouped under property, personal, drug and other misdemeanor offenses with no separate category for trespasses2. 1 Additional analysis of the racial disparities in the Erie County Criminal Justice system will be conducted in the near future but the trends are highly likely to mirror those of Open Buffalo’s report ‘Alarming Disparities: The Disproportionate Number of African American and Hispanic People in Erie County Criminal Justice System’.3 BEST PRACTICES: This report specifically looks at the reporting and public accessibility standards adopted and implemented by two of the country’s most scrutinized police departments and their best practices i.e. the New York Police Department (NYPD) and the Boston Police Department (Boston PD). There will also be a brief look at the data collection practices of police departments in other major cities namely Philadelphia, Chicago and Los Angeles. I. Boston Police Department: The Boston PD uses a Field Interrogation/Observation/Encounters (FIOE) report that is made when a police officer interrogates, observes, stops, frisks or searches a civilian. Boston PD’s Rule 323 required officers to complete these reports after “observ[ing], detain[ing], or interrogat[ing] a person suspected of unlawful design,” after “frisk[ing] or Boston PD’s Rule 323 required officers to complete these reports after “observ[ing], detain[ing], or interrogat[ing] a person suspected of unlawful design,” after “frisk[ing] or search[ing] an individual during a stop,” and after searching vehicles search[ing] an individual during a stop,” and after searching vehicles4. In a March 9,2011 memo circulated to Boston PD, Police Commissioner, Edward Davis explained that Section 3.2 of the Rule 323 defines a “Field Interaction/Stop” as “ brief detainment of an individual, whether on foot or in a vehicle, based on reasonable suspicion for the purposes of determining the individual’s identity and resolving the officer’s suspicions”5. Section 3.3 defines “Frisk” 2 as “pat down of the outer clothing, and the area within immediate control of the person for weapons” and allows frisking only when there exist “objective articulable facts” that could lead an officer to believe that person is “armed, and thus poses a threat to the officer or others”. Section 4 requires a FIOE report to include “basis for a stop” and other supporting information needed to establish “reasonable suspicion” or the presence of a “legitimate intelligence purpose”6. The section also asks officers to record race/ethnicity as well as date, time and location of the encounter. Section 5 instructs on duty police officers to carry FIOE forms; to complete them in ink and submitted to a detective supervisor at the end of duty; asks supervisors to review FIOE’s for “legibility, articulation of justification and completeness”; and finally submission by officer into the FIOE database within forty-eight hours of approval7. The FIOE Reports of the Boston Police Department were made available, even though in limited form, to independent researchers for investigation such as the American Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts8. It would aid in police accountability and community-law enforcement trust building if the Buffalo Police Department (BPD) were to be asked to report and record police-civilian encounter similar to Boston PD’s FIOE’s through city legislature initiatives, BHMA contracts or department policy guidelines. Interestingly, per the ACLU of Massachusetts, Boston police used “investigate person” Use of “investigate person” as a reason for interrogation, observation, frisk or search is insufficient in explaining or understanding if law enforcement action was legitimate and if the officer has reasonable articulable suspicion to do so. as a reason for interrogation, observation, frisk or search which is insufficient in explaining or understanding if law enforcement action was legitimate and if the officer has reasonable articulable suspicion to do so.9 One must attempt 3 to determine if similar explanations are used by Buffalo PD in its stop and frisk activities on BMHA properties. Best Practices Recommendations: Best practices recommended by the ACLU of Massachusetts to Boston PD that should be replicated in Buffalo include issuance of receipts by officers to civilians in case of any encounters if interrogated, stopped, frisked or searched regardless of ensuing arrest and whether the encounter was consented to10. The receipts would identify officer, time, Best practices recommended by the ACLU . . . include issuance of receipts by officers to civilians in case of any encounters if interrogated, stopped, frisked or searched regardless of ensuing arrest and whether the encounter was consented to. place, legal basis for encounter and means of filing a complaint. A focus must be made in ensuring all officers complete a detailed police report upon encounter as well as a supervisory review of all police-civilians encounters forms including corrective action when officers fail to complete the form. II. The New York Police Department (NYPD): UF-250 Civilian-Police Encounter Forms: NYPD uses a form named UF-250 to document “stop and frisk” encounters. Officers are required to record information such as: The name, age, gender, physical description, race and other pedigree information of the person “stopped”; The name, tax identification number, and command of the officer who performed the “stop”; The time, place and precinct where the “stop” occurred; 4 The suspected charge which gave rise to the “stop”; The “factors which caused the officer to reasonably suspect the person stopped ([i]nclud[ing] information from third persons and their identity, if known)”; Whether the officer used force to effect the “stop”; Whether a frisk was conducted and, if so, whether a weapon or contraband was seized; Whether a search of the inside of the suspect’s clothing was conducted and, if so, the basis for that search; and Whether the person “stopped” was arrested and, if so, on what charge11 12. Additionally, department policy requires that the officers be required to complete a UF-250 form under four specific circumstances Supervisors are responsible for ensuring that officers are able to “articulate sufficient levels of suspicion” for their actions and if violations are committed, to then discipline or retrain the officer such as when a suspect is 1. “Stopped by force”; (2) frisked i.e. pat down and/or searched; (3) arrested; or (4) “stopped” and refusal to identify him or herself. Similar to Boston, officers are required to submit the completed form to their supervisors who review and sign it. Supervisors are responsible for ensuring that officers are able to “articulate sufficient levels of suspicion” for their actions and if violations are committed, to then discipline or retrain the officer.13 Analogous to Boston PD’s use of ‘investigative person’ as an insufficiently detailed or legitimate reason for ‘stop and frisk’ NYPD’s use of ‘furtive movement’ in 51.3% of their stops and frisks was deemed too vague to be justifiable enough by the Floyd court14. 5 Best Practices Recommendation: In a situation closely resembling the practices on Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority (BMHA) properties, a preliminary settlement agreement on January 7, 2015 concluded the five-year long federal class-action lawsuit between residents/guests of New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) properties and the NYPD. The settlement puts an end to the NYPD’s enforcement of criminal trespass laws on NYCHA by the appointment of court-appointment monitors that were decreed in the Floyd case by Judge Shira [public housing] residents and their authorized visitors have the same legal rights as the residents and authorized visitors of any other residential building in New York City, and deserve the utmost courtesy and respect Scheindlein15. Most notably for the BMHA situation, the settlement unequivocally states that “NYCHA residents and their authorized visitors have the same legal rights as the residents and authorized visitors of any other residential building in New York City, and deserve the utmost courtesy and respect”16. The settlement also asks for revisions to the NYPD Patrol guide on interior patrols in NYC public housing properties; requires the NYPD to document all trespass arrests conducted in NYC public housing and curiously, also modifies public housing rules on resident cooperation with the NYPD and the prohibitions on ‘lingering’17. This settlement could be crucial in negotiations with the Buffalo Police Department given the precedent now set for the state as a whole. The impending risk of litigation and the costs that will be incurred by the city during the litigation and by the ensuing possible settlement agreements including use of a court-appointed monitor might make it palatable for the BPD to cease its aggressive ‘stop and frisk’ practices as well as mandate documentation for its officers. 6 Public Access to Records: The NYPD operates a ‘Stop, Question and Frisk Report Database’ from the years 20032014 that is accessible on the city’s website18. Even though the NYPD has led the way in successfully collecting and making available raw stop and frisk data, the inaccessibility of the format (.por.) has left room for The NYPD operates a ‘Stop, Question and Frisk Report Database’ from the years 2003-2014 that is accessible on the city’s website . . . available in multiple formats making it accessible to the general public and easier to use, a format that needs to be continued and replicated country-wide improvement. This file type has typically required the use of expensive software that only governmental agencies and academics possess for statistical analysis. Thus, the average citizen is unable to access this readily available data and process the information for monitoring purposes. However, in 2008, the NYPD made its 2006 stop and frisk data available in multiple formats making it accessible to the general public and easier to use, a format that needs to be continued and replicated country-wide. The recent release of the NYPD’s stop and frisk 2014 data was available in both .por and .csv formats19. Data Collection Methodology and Public Accessibility in Philadelphia, Chicago and LA: The Philadelphia Police Department (PPD), like NYPD, was moved into making its stop and frisk data available pursuant to a court decree in the 2011 case, Bailey v. City of Philadelphia that was fought by the ACLU of Pennsylvania (ACLU-PA)20. The court ordered PPD to implement an electronic database that would collect detailed and analyzable stop and frisk data; which the city did in 2014 (by entering their 75-48a pedestrian/vehicle stop reports into the database). The ACLU-PA in it’s fifth court7 mandated report pointed out that while stop and frisks without reasonable suspicion …while stop and frisks without reasonable suspicion were still high …plummeted to 39 percent of all stop and frisks from 50 percent in 2011 when the decree was entered [to implement an electronic database for stop and frisk data] were still high, they had plummeted to 39 percent of all stop and frisks from 50 percent in 2011 when the decree was entered21. In that report, the ACLU-PA blamed the still high and unlawful levels of stop and frisk on the lack of accountability of “officers and their immediate supervisors”.22 Owing to The Rampart Division Scandal (an anti-gang unit involved in unwarranted shootings and beatings) in the late 1990’s, the Department of Justice in 2001 put the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) under a consent decree requiring the collection of field data as well as an independent review of stop and frisk data23. Unfortunately, after 2009, the last year in which the consent decree applied; LAPD has stopped collecting stop and frisk data24. In Chicago, litigation attempts were dismissed or failed (most notably in the case of Olympic gold medalist Shani Davis in Davis v. City of Chicago) although it was found that the Chicago Police Department (CPD) used contact information cards during stop and frisk25. These contact information cards were and are not specific enough to point to the type of civilian-police encounter namely whether it is a Terry stop or gang/narcotics-relating loitering. Crucially, the current CPD practice in using contact information cards involves officers narrating details of the incident purely in narrative form instead of ticking off specific categories for issues like reasons for stop, description of crime and suspect as well as if the person was frisked, searched and produced contraband or weapons26. This raises difficulties in determining with 8 sufficient certainty the scale of stop and frisk and must be avoided in Buffalo in the near future if BPD agrees to undertake information gathering on such encounters. In contrast to all the data collection practices listed in this report, the Buffalo Commission on Citizens’ Rights and the Buffalo Commission on Citizens’ Rights and Community Relations only deals with filing and pursuit of police misconduct and providing recommendations… but it does not sanction or monitor civilian-police encounters, as it should be allowed to… Community Relations only deals with filing and pursuit of police misconduct and providing recommendations to city officials on improving community relations as well as respect for citizens’ rights. It does also review police investigation of misconduct but it does not sanction or monitor civilian-police encounters, as it should be allowed to by court decree or legislation. 9 WORKS CITED: 1 Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. (1968) (The Supreme Court held that tt is a reasonable search when an officer performs a quick seizure and a limited search for weapons on a person that the officer reasonably believes could be armed.) 2 See, Exhibit 1: Misdemeanor Arrests in New York State and Erie County for 2009-14 by Age and Ethnicity, attached. 3 Erin Carman, Open Buffalo, Alarming Disparities: The Disproportionate Number of African American and Hispanic People in Erie County Criminal Justice System (2013). 4 American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Foundation of Massachusetts, Black, Brown and Targeted: A report on Boston Police Department Street Encounters from 2007-2010 (2014) at 3. 5 See, Exhibit 2: Memo on Boston Police Department Rules and Procedures relating to Rule 323, attached. 6 See, Exhibit 2, attached. 7 See, Exhibit 2, attached. 8 Black, Brown and Targeted at 4-5. 9 Id. at 11. 10 Id. at 15-16. 11 Report of the OAG’s “Stop & Frisk” Investigation, Eliot L. Spitzer, Attorney General, March 18, 1999 at 63-65. 12 Greg Ridgeway, Center on Quality Policing, Analysis of Racial Disparities in the New York Police Department’s Stop, Question, and Frisk Practices (2007) at 54-55 (the pages contain a copy of the UF-250 forms). 13 Id. 14 Floyd v. City Of New York, 959 F. Supp. 2d 540, 559 (S.D.N.Y 2013). 15 National Association of Colored Peoples (NAACP) Legal Defense & Education Fund (LDF), Preliminary Settlement Reached in Federal Class Action Lawsuit Challenging Police Practices in NYC Public Housing; Major NYPD Reforms to be Implemented in Court-ordered Monitoring Process, available at http://www.naacpldf.org/update/preliminary-settlement-reached-federal-class-action-lawsuitchallenging-police-practices-nyc-. 16 Id. 17 Id. 18 New York Police Department, NYPD Stop, Question and Frisk Report Database, available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/nypd/html/analysis_and_planning/stop_question_and_frisk_report.shtml. 19 Becca James, Stop and Frisk in 4 cities: The importance of open police data, Sunlight Foundation blog (March 2, 2015), http://sunlightfoundation.com/blog/2015/03/02/stop-and-frisk-in-4-cities-the-importanceof-open-police-data-2/. 20 Bailey v. City of Philadelphia,C.A. No. 10-5952 (E.D. Pa. 2011). 21 Bailey v. City of Philadelphia,C.A. No. 10-5952 (E.D. Pa. 2011) ( ‘Plaintiffs’ Fifth Report to Court and Monitor on Stop and Frisk Practices’). 22 Id. 23 Supra, note 19. 24 Supra, note 19. 25 Supra, note 19. 26 Supra, note 19. 10