Paige – Seizure & Other Seizure Disorders

advertisement

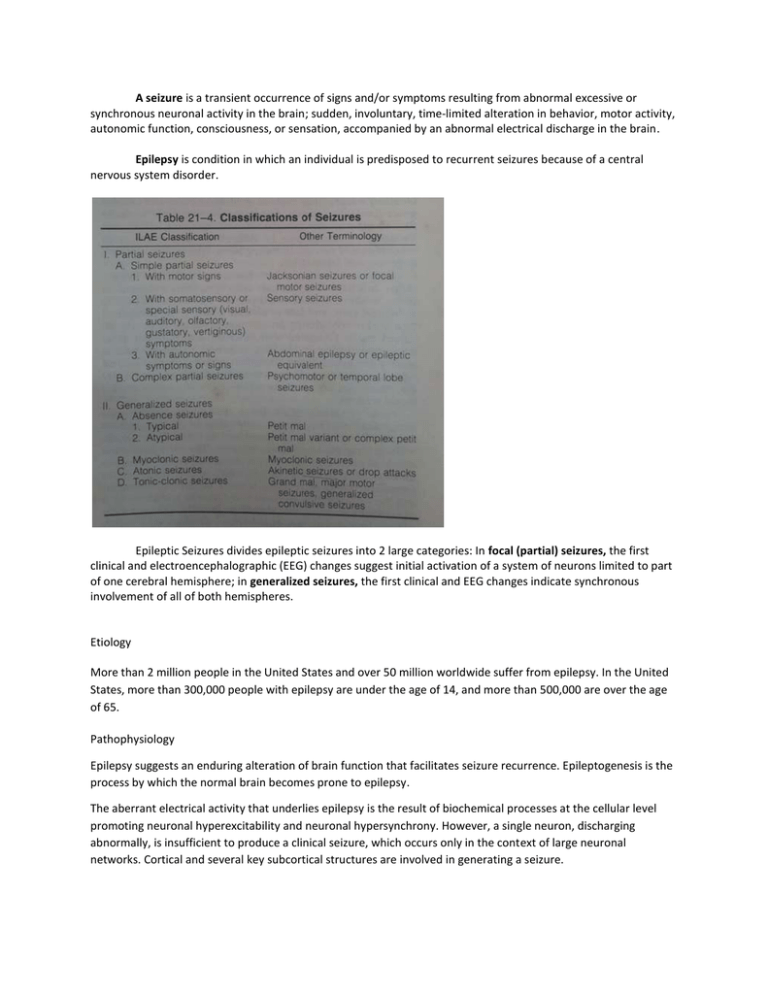

A seizure is a transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms resulting from abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain; sudden, involuntary, time-limited alteration in behavior, motor activity, autonomic function, consciousness, or sensation, accompanied by an abnormal electrical discharge in the brain. Epilepsy is condition in which an individual is predisposed to recurrent seizures because of a central nervous system disorder. Epileptic Seizures divides epileptic seizures into 2 large categories: In focal (partial) seizures, the first clinical and electroencephalographic (EEG) changes suggest initial activation of a system of neurons limited to part of one cerebral hemisphere; in generalized seizures, the first clinical and EEG changes indicate synchronous involvement of all of both hemispheres. Etiology More than 2 million people in the United States and over 50 million worldwide suffer from epilepsy. In the United States, more than 300,000 people with epilepsy are under the age of 14, and more than 500,000 are over the age of 65. Pathophysiology Epilepsy suggests an enduring alteration of brain function that facilitates seizure recurrence. Epileptogenesis is the process by which the normal brain becomes prone to epilepsy. The aberrant electrical activity that underlies epilepsy is the result of biochemical processes at the cellular level promoting neuronal hyperexcitability and neuronal hypersynchrony. However, a single neuron, discharging abnormally, is insufficient to produce a clinical seizure, which occurs only in the context of large neuronal networks. Cortical and several key subcortical structures are involved in generating a seizure. Focal seizures may be localized lesion, but investigation of focal seizures during childhood may be nondiagnostic. Focal seizures in a neonate may be seen in perinatal stroke. Motor seizures may be focal or generalized and tonic-clonic, tonic, clonic, myoclonic, or atonic. Tonic seizures are characterized by increased tone or rigidity, and atonic seizures are characterized by flaccidity or lack of movement during a convulsion. Clonic seizures consist of rhythmic muscle contraction and relaxation; myoclonus is most accurately described as shocklike contraction of a muscle. The duration of the seizure and state of consciousness (retained or impaired) should be documented. The history should determine whether an aura preceded the convulsion and the behavior of the child immediately preceding the seizure. The most common aura experienced by children consists of epigastric discomfort or pain and a feeling of fear. The posture of the patient, presence and distribution of cyanosis, vocalizations, loss of sphincter control (particularly of the urinary bladder), and postictal state (including sleep, headache, and hemiparesis) should be noted. I. Partial seizures A. SIMPLE PARTIAL SEIZURES These can take the form of sensory seizures (auras) or brief motor seizures, the specific nature of which gives clues as to the location of the seizure focus, as described earlier. Brief motor seizures are the most common and include (focal tonic, clonic or atonic seizures. Often there is a motor (Jacksonian) march from face to arm to leg, adversive head and eye movements to the contralateral side, or postictal (Todd’s) paralysis that can last minutes or hours, and sometimes longer. Unlike tics, motor seizures are not under partial voluntary control; seizures are more often stereotyped and less likely than tics to manifest different types in a given patient. B. COMPLEX PARTIAL SEIZURES Complex partial seizures usually last 1-2 min and are often preceded by an aura, such as a rising abdominal feeling, déjà vu or déjà vécu, a sense of fear, complex visual hallucinations, micropsia or macropsia (temporal lobe), generalized difficult-tocharacterize sensations (frontal lobe), focal sensations (parietal lobe), or simple visual experiences (occipital lobe). Children <7 yr old are less likely than older children to report auras, but parents might observe unusual preictal behaviors that suggest the experiencing of auras. Subsequent manifestations consist of decreased responsiveness, staring, looking around seemingly purposelessly, and automatisms. Automatisms are automatic semipurposeful movements of the mouth (oral, alimentary such as chewing) or of the extremities (manual, such as manipulating the sheets; leg automatisms such as shuffling, walking). Often there is salivation, dilation of the pupils, and flushing or color change. The patient might appear to react to some of the stimulation around him or her but does not later recall the epileptic event. At times, walking and/or marked limb flailing and agitation occur, particularly in patients with frontal lobe seizures. Frontal lobe seizures often occur at night and can be very numerous and brief, but other complex partial seizures from other areas in the brain can also occur at night. There is often contralateral dystonic posturing of the arm and, in some cases, unilateral or bilateral tonic arm stiffening. Some seizures have these manifestations with minimal or no automatisms. Others consist of altered consciousness with contralateral motor, usually clonic, manifestations. After the seizure, the patient can have postictal automatisms, sleepiness, and/or other transient focal deficits such as weakness or aphasia. C. SECONDARY GENERALIZED SEIZURES Secondary generalized seizures can start with generalized clinical phenomena (due to rapid spread of the discharge from the initial focus), or as simple or complex partial seizures with subsequent clinical generalization. There is often adversive eye and head deviation to the contralateral side followed by generalized tonic, clonic, or tonic-clonic activity. Tongue biting, urinary and stool incontinence, vomiting with risk of aspiration, and cyanosis are common. Fractures of the vertebrae or humerus are rare complications. Most such seizures last 1-2 min. Tonic focal or secondary generalized seizures often manifest adversive head deviation to the contralateral side, or fencing, hemi- or full figure-of-four arm, or Statue of Liberty postures. These postures often suggest frontal origin, particularly when consciousness is preserved during them, indicating that the seizure originated from the medial frontal supplementary motor area. EEG in patients with partial seizures usually shows focal spikes or sharp waves in the lobe where the seizure originates. A sleep-deprived EEG with recording during sleep increases the diagnostic yield and is advisable in all patients whenever possible. Despite that, about 15% of children with epilepsy initially have normal EEGs because the discharges are relatively infrequent or the focus is deep. If repeating the test does not detect paroxysmal findings, then 24-hour video EEG monitoring may be helpful and can allow visualization of the clinical events and the corresponding EEG tracing. Brain imaging is critical in patients with focal seizures. In general, MRI is preferable to CT and can show pathologies such as changes due to previous strokes or hypoxic injury, malformations, medial temporal sclerosis, arteriovenous malformations, or tumors. II. Generalized seizures A. ABSENCE SEIZURES Typical absence seizures usually start at 5-8 yr of age and are often, owing to their brevity, overlooked by parents for many months even though they can occur up to hundreds of times per day. Unlike complex partial seizures they do not have an aura, usually last for only a few seconds, and are accompanied by flutter or upward rolling of the eyes but typically not by automatisms of the complex partial seizure type (absence seizures can have simple automatisms like lip-smacking or picking at clothing and the head can minimally fall forward). Absence seizures do not have a postictal period and are characterized by immediate resumption of what the patient was doing before the seizure. Hyperventilation for 3-5 min can precipitate the seizures and the accompanying 3 Hz spike–and–slow wave discharges. The presence of periorbital, lid, perioral or limb myoclonic jerks with the typical absence usually predicts difficulty in controlling the seizures with medication. Atypical absence seizures have associated myoclonic components and tone changes of the head and body and are also usually more difficult to treat. They are precipitated by drowsiness and are usually accompanied by 1-2 Hz spike–and–slow wave discharges. Juvenile absence seizures are similar to typical absences but occur at a later age and are accompanied by 4-6 Hz spike–and– slow wave and polyspike–and–slow wave discharges. These are usually associated with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. B. GENERALIZED MOTOR SEIZURE The most common generalized motor seizures are generalized tonic-clonic seizures that can be either primarily generalized (bilateral) or secondarily generalized from a unilateral focus. If there is no partial component then the seizure usually starts with loss of consciousness and at times with a sudden cry, upward rolling of the eyes, and a generalized tonic contraction with falling, apnea, and cyanosis. In some, a clonic or myoclonic component precedes the tonic stiffening. The tonic phase is followed by a clonic phase that, as the seizure progresses, shows slowing of the rhythmic contractions until the seizure stops usually 1-2 min later. Incontinence and postictal period often follow. The latter usually lasts for 30 min to several hours with semicoma or obtundation and postictal sleepiness, ataxia, hyper- or hyporeflexia, and headaches. There is a risk of aspiration and injury. First aid measures include positioning the patient on his or her side, clearing the mouth if it is open, loosening tight clothes or jewelry, and gently extending the head and, if possible, insertion of an airway by a trained professional. The mouth should not be forced open with a foreign object (this could dislodge teeth, causing aspiration) or with a finger in the mouth (this could result in serious injury to the examiner’s finger). Many patients have single idiopathic generalized tonic-clonic seizures that may be associated with intercurrent illness or with a cause that cannot be ascertained. Generalized tonic, atonic, and astatic seizures often occur in severe pediatric epilepsies. Generalized myoclonic seizures can occur in either benign or difficult-to-control epilepsies. C. BENIGN GENERALIZED EPILEPSIES Petit mal epilepsy typically starts in mid-childhood, and most patients outgrow it before adulthood. Approximately 25% of patients also develop generalized tonic-clonic seizures, half before and half after the onset of absences. Benign myoclonic epilepsy of infancy consists of the onset of myoclonic and other seizures during the 1st yr of life, with generalized 3 Hz spike–and–slow wave discharges. Often it is initially difficult to distinguish this type from more-severe syndromes, but follow-up clarifies the diagnosis. Febrile seizures plus syndrome manifests febrile seizures and multiple types of generalized seizures in multiple family members, and at times different individuals within the same family manifest different generalized and febrile seizure types. Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (Janz syndrome) is the most common generalized epilepsy in young adults, accounting for 5% of all epilepsies. Typically, it starts in early adolescence with one or more of the following manifestations: myoclonic jerks in the morning, often causing the patient to drop things; generalized tonic clonic or clonic-tonicclonic seizures upon awakening; and juvenile absences. Sleep deprivation, alcohol (in older patients), and photic stimulation or, rarely, certain cognitive activities can act as precipitants. The EEG usually shows generalized 4-5 Hz polyspike–and– slow wave discharges. There are other forms of generalized epilepsies such as photoparoxysmal epilepsy, in which occipital, generalized tonic clonic, absence or myoclonic generalized seizures are precipitated by photic stimuli such as flipping through TV channels and viewing video games. Other forms of reflex (i.e., stimulusprovoked) epilepsy can occur; associated seizures are usually generalized, although some may be focal. Absence petit mal sudden cessation of motor activity or speech with a blank facial expression and flickering of the eyelids more prevalent in girls rarely persist longer than 30 sec do not lose body tone Generalized tonic-clonic grand mal suddenly lose consciousness and in some cases emit a shrill, piercing cry eyes roll back, their entire body musculature undergoes tonic contractions, and they rapidly become cyanotic in association with apnea clonic phase of the seizure is heralded by rhythmic clonic contractions alternating with relaxation of all muscle group A. Myoclonic Seizures Myoclonic seizures are divided into focal, multifocal, and generalized types. Myoclonic seizures can be distinguished from clonic seizures by the rapidity of the jerks and by their lack of rhythmicity. Focal myoclonic seizures characteristically affect the flexor muscles of the upper extremities and are sometimes associated with seizure activity on EEG. Multifocal myoclonic movements involve asynchronous twitching of several parts of the body and are not commonly associated with seizure discharges on EEG. Generalized myoclonic seizures involve bilateral jerking associated with flexion of upper and occasionally lower extremities. The latter type of myoclonic jerks is more commonly correlated with EEG abnormalities than the other types. B. Clonic Seizures Clonic seizures can be focal or multifocal. Multifocal clonic seizures incorporate several body parts and are migratory in nature. The migration follows a non-Jacksonian trend; for example, jerking of the left arm can be associated with jerking of the right leg. Generalized clonic seizures, which are bilateral, symmetrical, and synchronous, are uncommon in the neonatal period presumably due to decreased connectivity associated with incomplete myelination at this age. C. Tonic Seizures Tonic seizures can be focal or generalized (generalized are more common). Focal tonic seizures include persistent posturing of a limb or posturing of trunk or neck in an asymmetric way often with persistent horizontal eye deviation. Generalized tonic seizures are bilateral tonic limb extension or tonic flexion of upper extremities often associated with tonic extension of lower extremities. D. Atonic seizures Atonic seizures, are usually longer and the loss of tone often develops more slowly. Febrile seizures Febrile convulsions, the most common seizure disorder during childhood Age dependent and are rare before 9 mo and after 5 yr of age. A strong family history of febrile convulsions. Usually generalized, is tonic-clonic and lasts a few seconds to 10-min Mapped the febrile seizure gene to chromosomes 19p and 8q13-21. A simple febrile seizure is a primary generalized, usually tonic-clonic, attack associated with fever, lasting for a maximum of 15 min, and not recurrent within a 24-hour period. Complex febrile seizure is more prolonged (>15 min), is focal, and/or recurs within 24 hr. Febrile status epilepticus is a febrile seizure lasting >30 min. Acute symptomatic seizures occur secondary to an acute problem affecting brain excitability such as electrolyte imbalance or meningitis. Most children with these types of seizures do well, but sometimes such seizures signify major structural, inflammatory, or metabolic disorders of the brain, such as meningitis, encephalitis, acute stroke, or brain tumor; the prognosis depends on the underlying disorder, including its reversibility or treatability and the likelihood of developing epilepsy from it. Unprovoked seizure is not an acute symptomatic seizure. Remote symptomatic seizure is thought to be secondary to a distant brain injury such as an old stroke. Epileptic syndrome is a disorder that manifests one or more specific seizure types and has a specific age of onset and a specific prognosis. Status Epilepticus: More than thirty minutes of continuous seizure activity, or recurrent seizures without intercurrent recovery of consciousness Epilepsy is a disorder of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate seizures and by the neurobiologic, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition. The clinical diagnosis of epilepsy usually requires the occurrence of at least 1 unprovoked epileptic seizure with either a second such seizure or enough EEG and clinical information to convincingly demonstrate an enduring predisposition to develop recurrences. For epidemiologic purposes epilepsy is considered to be present when ≥2 unprovoked seizures occur in a time frame of >24 hr. Approximately 4-10% of children experience at least 1 seizure in the first 16 yr of life. The cumulative lifetime incidence of epilepsy is 3%, and more than half of the cases start in childhood. The annual prevalence is 0.5-1%. Thus, the occurrence of a single seizure or of febrile seizures does not necessarily imply the diagnosis of epilepsy. Seizure disorder is a general term that is usually used to include any one of several disorders including epilepsy, febrile seizures, and possibly single seizures and seizures secondary to metabolic, infectious, or other etiologies (e.g., hypocalcemia, meningitis). An epileptic syndrome is a disorder that manifests one or more specific seizure types and has a specific age of onset and a specific prognosis. Several types of epileptic syndromes can be distinguished epileptic encephalopathy is an epilepsy syndrome in which the severe EEG abnormality is thought to result in cognitive and other impairments in the patient. Idiopathic epilepsy is an epilepsy syndrome that is genetic or presumed genetic and in which there is no underlying disorder affecting development or other neurologic function (e.g., petit mal epilepsy). Symptomatic epilepsy is an epilepsy syndrome caused by an underlying brain disorder (e.g., epilepsy secondary to tuberous sclerosis). cryptogenic epilepsy (also termed presumed symptomatic epilepsy) is an epilepsy syndrome in which there is a presumed underlying brain disorder causing the epilepsy and affecting neurologic function, but the underlying disorder is not known. Treatment In general, antiepileptic therapy, continuous or intermittent, is not recommended for children with one or more simple febrile seizures. Parents should be counseled about the relative risks of recurrence of febrile seizures and recurrence of epilepsy, educated on how to handle a seizure acutely, and given emotional support. If the seizure lasts for >5 min, then acute treatment with diazepam, lorazepam, or midazolam is needed. Rectal diazepam is often prescribed to be given at the time of recurrence of febrile seizure lasting buccal or intranasal midazolam may be used and is often preferred by parents. Intravenous benzodiazepines, phenobarbital, phenytoin, or valproate may be needed in the case of febrile status epilepticus. If the parents are very anxious concerning their child’s seizures, intermittent oral diazepam can be given during febrile illnesses (0.33 mg/kg every 8 hr during fever) to help reduce the risk of seizures in children known to have had febrile seizures with previous illnesses. Intermittent oral nitrazepam, clobazam, and clonazepam (0.1 mg/kg/day) have also been used. Other therapies have included intermittent diazepam prophylaxis (0.5 mg/kg administered as a rectal suppository every 8 hr), Phenobarbital (4-5 mg/kg/day in 1 or 2 divided doses), and valproate (20-30 mg/kg/day in 2 or 3 divided doses). In the vast majority of cases it is not justified to use these medications owing to the risk of side effects and lack of demonstrated long-term benefits, even if the recurrence rate of febrile seizures is expected to be decreased by these drugs. Other antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) have not been shown to be effective. Antipyretics can decrease the discomfort of the child but do not reduce the risk of having a recurrent febrile seizure, probably because the seizure often occurs as the temperature is rising or falling. Chronic antiepileptic therapy may be considered for children with a high risk for later epilepsy. Currently available data indicate that the possibility of future epilepsy does not change with or without antiepileptic therapy. Iron deficiency has been shown to be associated with an increased risk of febrile seizures, and thus screening for that problem and treating it appears appropriate. Mimicking seizures Benign paroxysmal vertigo Benign paroxysmal vertigo occurs in young children and consists of abrupt episodes of unsteadiness or ataxia. Benign paroxysmal vertigo is a frequent etiology of childhood dizziness. The child may appear startled or frightened by the sudden loss of balance, which is accompanied by brief nystagmus and/or pallor; consciousness is always preserved. The diagnosis of benign paroxysmal vertigo is based on the clinical history, but the differential includes posterior fossa tumors or cervical spine abnormalities, otological pathology, epilepsy (benign occipital epilepsy), or metabolic disorders. Benign paroxysmal vertigo is primarily a disorder of infants and preschool children. The disorder may, however, develop in older children. The onset is usually between 2 and 8 years of age, but cases beginning before 6 months of age have been described. An otherwise normal child suddenly, and without warning, becomes vertiginous. Vertigo is so profound that even a sitting posture cannot be maintained. Neither the initiation nor the severity of the attack is influenced by head or body position. The child becomes pale, is clearly frightened, and may lie motionless on the floor. Infants indicate the need to be held by a parent. Consciousness is not altered, and headache is not reported. Verbal children always describe that either they are rotating or the environment is spinning. The sensation of rotation is the initial and primary feature of the attack. Nausea or other abdominal discomfort may follow. Episodes usually last for seconds or minutes, but on rare occasions they may continue for hours. The child wishes to remain absolutely still. After the vertigo subsides, the child is unstable and briefly appears ataxic. Nystagmus accompanies the vertigo, but is often not reported. The neurologic examination is otherwise normal. The attacks are stereotyped. Episodes can recur at irregular intervals—sometimes several in 1 week. More often, they recur once a month or less. With time, the attacks either cease completely or evolve into a more common migraine syndrome. The evolution of the condition may first include the additional feature of vomiting and then headache with the vertigo. The vertigo becomes progressively less severe and may disappear altogether. Some children complain of vertigo or dizziness as an initial feature of later migraine attacks. The results of investigations of vestibular and auditory function in children with benign paroxysmal vertigo have been in conflict, but no convincing data indicating pathology of the peripheral or central vestibular system have been definitively demonstrated. Basser's original assertions may be supported by the development of abnormalities in rotational testing, unilateral reduced caloric responsiveness, and vestibular system dysfunction patterns on posturography in patients with chronic migraine-related benign paroxysmal vertigo Night terrors The sleep disorder of night terrors typically occurs in children aged 3-12 years, with a peak onset in children aged 3½ years. Night terrors are distinctly different from the much more common nightmares, which occur during REM sleep. Night terrors are characterized by frequent recurrent episodes of intense crying and fear during sleep, with difficulty arousing the child. Night terrors are frightening episodes that disrupt family life. An estimated 1-6% of children experience night terrors. Boys and girls are equally affected. Children of all races also seem to be affected equally. The disorder usually resolves during adolescence. In addition to frequent recurrent episodes of intense crying and fear during sleep, with difficulty arousing the child, children with night terrors may also experience the following: Tachycardia (increased heart rate) Tachypnea (increased breathing rate) Sweating during episodes Unlike nightmares, most children do not recall a dream after a night terror episode, and they usually do not remember the episode the next morning. The typical night terror episode usually begins approximately 90 minutes after falling asleep. The child sits up in bed and screams, appearing awake but is confused, disoriented, and unresponsive to stimuli. Although the child seems to be awake, the child does not seem to be aware of the parents' presence and usually does not talk. The child may thrash around in bed and does not respond to comforting by the parents. Most episodes last 1-2 minutes, but they may last up to 30 minutes before the child relaxes and returns to normal sleep. If the child does awake during a night terror, only small pieces of the episode may be recalled. Usually, the child does not remember the episode upon waking in the morning. Breath-holding spells Breath-holding spells (or attacks) are not uncommon in toddlers and can sometimes occur in young babies. They occur in about one in twenty children. A breath-holding spell may happen after a child has an upset or sudden startle, such as a minor bump or a fright. The child opens their mouth as if to cry but nothing comes out. They then can look deathly pale or go blue around the lips. The child may become limp and fall to the ground. Convulsive movements of their limbs may then occur. The child may recover quickly or be unresponsive for a short period. Breath-holding spells often occur as part of toddler tantrums. The spell is a reflex reaction to an unpleasant stimulus, which the child can’t prevent. It is not a deliberate behaviour on the child’s part. Syncope Syncope is a sudden, brief loss of consciousness associated with loss of postural tone from which recovery is spontaneous. Up to 15 percent of children experience a syncopal episode prior to the end of adolescence. Although the etiology of syncopal events in children is most often benign, syncope can also occur as the result of more serious (usually cardiac) disease with the potential for sudden death. The vast majority of cases of syncope in the pediatric age group represent benign alterations in vasomotor tone. Life-threatening causes of syncope generally have a cardiac etiology. Paroxysmal kinesigenic Choreoathetosis Paroxysmal kinesigenic choreathetosis (PKC) also called Paroxysmal Kinesigenic Dyskinesia (PKD) is a hyperkinetic movement disorder characterized by attacks of involuntary movements, which are triggered by sudden voluntary movements. The number of attacks can increase during puberty and decrease in a person’s 20's to 30's. Involuntary movements can take many forms such as ballism, chorea or dystonia and usually only affect one side of the body or one limb in particular. This rare disorder only affects about 1 in 150,000 people with PKD accounting for 86.8% of all the types of paroxysmal dyskinesias and occurs more often in males than females. There are two types of PKD, primary and secondary. Primary PKD can be further broken down into familial and sporadic. Familial PKD, which means the individual has a family history of the disorder, is more common, but sporadic cases are also seen.[3] Secondary PKD can be caused by many other medical conditions such as multiple sclerosis (MS), stroke, pseudohypoparathyroidism, hypocalcemia, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, central nervous system trauma, or peripheral nervous system trauma.[5] PKD has also been linked with infantile convulsions and choreoathetosis (ICCA) syndrme, in which patients have afebrile seizures during infancy (benign familial infantile epilepsy) and then develop paroxysmal choreoathetosis later in life. This phenomenon is actually quite common, with about 42% of individuals with PKD reporting a history of afebrile seizures as a child. Shuddering attacks Infant shudder syndrome usually makes itself known as early as four months of age, although some children may experience it later than that. The attacks can involve a rapid tremor of the head, shoulder, and trunk. Depending on the type of shudder syndrome, only the head of the child might shake. The infant may also stiffen the limbs, or arch the back. It can sometimes look like the child is shuddering from a chill. Fiercer attacks may look something like a seizure. These shudder attacks usually only last a few seconds but can occur many times throughout a day. Most often, shuddering attacks happen when eating. Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy The defining characteristic of BPT is a tilting or rotating of an infant’s head in recurrent episodes, for varying periods of time. Furthermore, the child’s trunk may bend in the same direction as the head, giving the baby an overall curved shape; this complaint is known as tortipelvis. In addition to this, the individual may also, but not necessarily, experiencevomiting, pallor, ataxia, agitation, infantile migraine, unsteadiness of gait upon learning to walk, general malaise and nystagmus. The periods in which the child’s head is tilted and other symptoms appear can last anywhere from a few minutes to a few days, with a frequency of anywhere from two per year to two per month. Hereditary chin trembling Hereditary chin trembling is a rare autosomal dominant disease often considered as an "essential tremor variant". The clinical and neurophysiological data obtained in a new white family lead to the suggestion that this abnormal involuntary movement is a focal variant of hereditary essential myoclonus. Narcolepsy Narcolepsy is a chronic sleep disorder, or dyssomnia, characterized by excessive sleepiness and sleep attacks at inappropriate times, such as while at work. People with narcolepsy often experience disturbed nocturnal sleep and an abnormal daytime sleep pattern, which often is confused with insomnia. Narcoleptics, when falling asleep, generally experience the REM stage of sleep within 5 minutes; whereas most people do not experience REM sleep until an hour or so later. Another one of the many problems that some narcoleptics experience is cataplexy, a sudden muscular weakness brought on by strong emotions (though many people experience cataplexy without having an emotional trigger). It often manifests as muscular weaknesses ranging from a barely perceptible slackening of the facial muscles to the dropping of the jaw or head, weakness at the knees (often referred to as "knee buckling"), or a total collapse. Rage attacks Rage attack is an intense or growing anger. It is associated with the Fight-or-flight response and oftentimes activated in response to an external cue, such as the murder of a loved one or some other kind of serious offense. The phrase, 'thrown into a fit of rage,' expresses the immediate nature of rage that occurs before deliberation. If left unchecked rage may lead to violence. Depression and anxiety lead to an increased susceptibility to rage and there are modern treatments for this emotional pattern. Pseudo seizures Pseudo seizure is an attack resembling an epileptic seizure but having purely psychological causes, lacking the electroencephalographic changes of epilepsy, and sometimes able to be stopped by an act of will. Masturbation Masturbation is the sexual stimulation of the genitals, usually to the point of orgasm. The stimulation can be performed using the hands, fingers, everyday objects, or dedicated sex toys. Mutual masturbation, masturbation with a partner, can be an alternative to sexual intercourse. Studies have found that masturbation is frequent in humans of both sexes and all ages, although there is variation. Various medical and psychological benefits have been attributed to a healthy attitude to sex in general and to masturbation in particular, and no causal relationship is known between masturbation and any form of mental or physical disorder. Acts of masturbation have been depicted in art worldwide since prehistory. While there was a period when it was subject to medical censure and social conservatism, it is considered a normal part of healthy life today. It is commonly mentioned in popular music as well as on television, in films and in literature.