Chest Compressions in Neonatal

advertisement

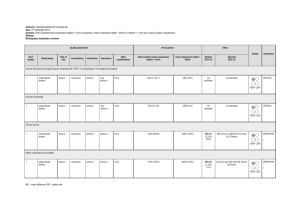

C0009 NRP® Current Issues Seminar: Monumental Changes on the Horizon Chest Compressions in Neonatal Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Vishal Kapadia, MD, MSCS, FAAP University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas Faculty Disclosure Information In the past 12 months, I have no relevant financial relationships with the manufacturer(s) of any commercial product(s) and/or provider(s) of commercial services discussed in this CME activity. I do not intend to discuss an unapproved/investigative use of a commercial product/device in my presentation. Session Objectives Describe indications of chest compressions during neonatal CPR Understand goal of cardiac compression during neonatal CPR Understand correct technique of neonatal chest compressions Discuss evidence behind current guidelines for neonatal CPR Anticipate Neonatal CPR You get a page for stat C/S 20 yo G1P0 mom, No prenatal care Clinical diagnosis of Chorioamnionitis Fetal bradycardia with loss of baseline variability Bedside sono suggest 39 wks How to Prepare for Neonatal CPR Assessment of perinatal risk Mobilization of the team Identification of team leader and pre-resuscitation briefing: Anticipating interventions and assigning roles. A standardized checklist to ensure that all necessary supplies and equipment are present and functioning Decide on an estimated weight May prepare umbilical catheter and may draw up intravenous epinephrine doses and label Going Back to Our Baby Baby is delivered, cord clamped and given to neonatal team Found to be not breathing and limp Airway positioned, secretions cleared, dried and stimulation provided Remains apneic and HR around 20 Positive pressure ventilation is initiated. Pulse oximeter is attached. Heart rate remains 20 bpm. What is the next step? If after initiation of PPV, HR remains < 60 You should A. Start chest compressions B. Stimulate the neonate C. Auscultate for full 1 minute for accurate HR assessment D. Attempt ventilation corrective steps: MRSOPA Indication of Cardiac Compression during Neonatal CPR If heart rate remains below 60 bpm despite adequate ventilation via advanced airway if possible. Ensure that assisted ventilation is being delivered optimally before starting chest compressions Ventilation is the most effective action in neonatal resuscitation. Chest compressions are likely to compete with effective ventilation Ventilation Corrective Steps Goal of Compressions Goal is to deliver sufficient oxygenated blood to the myocardium ( coronary) and to vital organs, especially brain. Coronary perfusion is a determinant of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). As oxygenated blood reaches the heart providing the energy (ATP), it may start beating again. Cerebral perfusion is a determinant of neurologic outcome Coronary Perfusion Pressure Coronary Perfusion Pressure=Aortic DBP – Right Atrial DBP Compressions with Diastolic BP Compressions with Minimal Diastolic BP Coronary Arteries ATPATP ATP Heart Heart Aorta α-adrenergic effects of epinephrine or uninterrupted compressions lead to Aorta Aortic DBP Adequate Diastolic Blood Pressure is Critical to the Success of CPR Coronary Perfusion Pressure = Aortic DBP – Right Atrial DBP C P P Compression Ventilation Robert A. Berg et al. Circulation. 2001;104:2465-2470 Optimal Neonatal Cardiac Compressions Location Compression depth Two thumbs versus Two finger Method Compression to ventilation ratio Synchronization Location: Lower 1/3 of Sternum You et al. Resuscitation 2009: Retrospective review of CT scan images. ( n= 75, mean age 4 ± 3 months) Left ventricle (Max AP diameter of heart ) located under lower third of sternum. Clements 2000 and Saini 2012 : Anatomic relationship between the nipples and lower sternum to determine finger position is not reliable. Running one’s fingers along the lower edge of the rib cage to locate the xiphoid, then placing the thumbs centrally and immediately above the xiphoid, avoiding direct pressure on the xiphoid. Compression Depth Chest compressions should be administered to a depth of approximately one-third of the AP diameter of the chest to produce a palpable pulse. The chest should be allowed to fully recoil before the next compression to allow the heart to refill with blood. Administer Compressions at a Depth of 1/3 the AP Diameter of the Chest – Retrospective observational study in neonates (n=54) – Mathematical modeling based upon neonatal chest CT scan dimensions – 1/3 AP chest depth should be more effective than 1/4 compression depth, and safer than 1/2 AP compression depth Meyer et al. Resuscitation 2010 What method of compressions should be used? Two thumb technique: Hands encircling the chest and thumbs depressing the sternum Two finger technique: Index and middle fingers to depress the sternum with the other hand behind the back providing a firm base Which technique is recommended for providing chest compressions? A. Two thumbs method B. Two fingers method C. Two thumbs method except when attempting line placement or managing airway D. The one you are most familiar with Use Two-Thumb Method Rather than Two-Finger Method for Neonatal Cardiac Compressions Use Two-Thumb Method Rather than Two-Finger Method for Neonatal Cardiac Compressions Use Two-Thumb (TT) Method Rather than Two-Finger (TF) Method 11 manikin RCTs including those using newborn manikin show with TT method: • • • • • Higher BP Appropriate compression depth Consistent correct placement on chest Less variance in compression quality Less fatigue over time Multiple human and neonatal observational studies and animal studies agree with superiority of two thumbs method. Two Finger Method Should Not be Used Disadvantages of two thumb method from the side of the bed. 1. No easy access to the umbilicus for line and medication. Many providers switch to TF method during line placement. 2. Must reach across the patient and body is not aligned to use large muscle groups for effective chest compressions. Head of Bed Compressions Allows Continuous Two-thumb Technique Once an airway is secured, move the compressor to head of bed Potential Advantages: Arms are in a more natural position, Umbilical access is more readily available while continuing Two-thumb technique, More space for person giving meds at the patient’s side Less compressor fatigue (Unpublished data, Sparks et al) Two finger method should no longer be used. What Ratio of Compression to Ventilation to Use (C:V ratio) In Adult V-fib model: problem with flow, not the content of the blood • Forward flow from left ventricle ceases • Blood has near normal carbon dioxide, oxygen and pH. • Emphasis on chest compression over ventilation In Neonatal asphyxial arrest, left ventricular blood has much lower oxygen tension, higher carbon dioxide and lower pH. • Neonatal CPR needs adequate airway and ventilation to oxygenate the blood and good quality chest compression to move that blood forward. In Asphyxia Animal Model, Chest Compression with Ventilation is Superior to Ventilation or Compression Alone CC + V (n=10) CCC (n=10) V (n=10) 7.42 ± 0.01 7.42 ± 0.02 7.40 ± 0.01 43 ± 1 42 ± 1 45 ± 2 7.20 ± 0.03 7.17 ± 0.04 7.23 ± 0.04 68 ± 5 77 ± 11 51 ± 3 10 (100%) 4 (40%) 6 ( 60%) Baseline (before asphyxia) Arterial pH Arterial pCO2 (mmHg) After 1 min of CPR Arterial pH Arterial pCO2 (mmHg) ROSC obtained in < 2 min, n (%)* *p 0.01 Berg RA et al. Circulation 2000 What Ratio of Compression to Ventilation to Use Study Year Design Total Pts Population Solevag 2010 RCT 32 Pigs (12-36 hrs) Solevag 2011 RCT 22 Pigs (12-36 hrs) Solevag 2012 RCT 2 (x 5 runs) Neo Resus Providers Dannevig 2012 RCT 31 Pigs (12-36 hrs) Dannevig 2013 RCT 54 Pigs ( 14-34 hrs) Hemway 2013 RCT 32 Neo Resus Providers Schmolzer 2014 RCT 16 Pigs (1-4 days) Compression to Ventilation Ratio 15:2 is Not Superior to 3:1 in Neonatal Asphyxia Model 3:1 (n=9) 15:2 (n=9) P Value 58 ± 7 75 ± 5 <0.001 4.8 ± 2.6 7.1 ± 2.8 0.004 2 2 NS 150 (140-180) 195 (145-358) NS pH following ROSC 6.6 ± 0.1 6.6 ± 0.1 NS pCO2 ( kPa) 11.2 ± 4.3 9.6 ± 2.7 NS Cardiac Compression/min Increase in DBP during compression cycles (mmHg) Number of animals with no ROSC Time to ROSC (sec)* DBP=Diastolic Blood Pressure, ROSC=return of spontaneous circulation Solevåg et al. ADC 2011 Continue Use of 3:1 Compression to Ventilation Ratio Animal studies: No advantage to higher C:V ratio for tissue injury, gas exchange during CPR, time to return of spontaneous circulation. Manikin studies ( Hemway 2013, Solevag 2012): disadvantage of higher ratio regarding compressor fatigue and minute ventilation. A 3:1 C:V ratio is recommended, with 90 compressions and 30 breaths to achieve approximately 120 events per minute to maximize ventilation at an achievable rate. Rescuers may consider using higher ratios (eg, 15:2) if the arrest is believed to be of cardiac origin Should we continue to coordinate the compressions and ventilations? Compressions and ventilations should be coordinated to avoid simultaneous delivery. Asynchronous CPR Appears Equivalent to 3:1 CPR in Asphyxiated Neonatal Pigs Term newborn piglets, 8/group After ROSC CCaV group had higher pCO2, lower pH and higher lactate. No difference in ◦ 3:1 ◦ 3:1 • Asynchronous − ROSC • Asynchronous − Survival − Hemodynamic parameters − Minute ventilation Schmölzer et al Resuscitation 2014 What is the recommended method to estimate heart rate during neonatal CPR? A. B. C. D. E. Auscultation Palpation of umbilical cord ECG monitor Pulse oximetry Palpation of radial pulse Continue Good Practice and Change in Practice Anticipate need for resuscitation Optimal assisted ventilation via advanced airway before starting chest compressions Use ECG monitor during CPR Always two thumb compressions. Move to head of the bed during emergent umbilical line placement. Continue 3:1 C:V ratio. Compress lower third of sternum. Avoid unnecessary interruption of chest compression as CPP drops when interrupted. Be aware of compressor fatigue and switch Evidence Based Resuscitation Guideline documents: Perlman JM, Wyllie J, Kattwinkel J, Wyckoff M, Aziz K, Guinsburg R, Kim HK, Liley H, Mildenhall L, Simon WM, Szyld E, Tamura M, Velaphi S. Part 7: Neonatal resuscitation: 2015 International consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Circulation 2015; In press. Wyckoff MH, Aziz K, Escobedo M, Kapadia V, Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, Simon W, Weiner GM, Zaichkin J. Part 13:Neonatal resuscitation: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2015; In press. References 1.Berg RA, Hilwig RW, Kern KB, Babar I, Ewy GA. Simulated mouth-to-mouth ventilation and chest compressions (bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation) improves outcome in a swine model of prehospital pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest. Critical care medicine. Sep 1999;27(9):1893-1899. 2.Berg RA, Hilwig RW, Kern KB, Ewy GA. "Bystander" chest compressions and assisted ventilation independently improve outcome from piglet asphyxial pulseless "cardiac arrest". Circulation. Apr 11 2000;101(14):1743-1748. 3.Braga MS, Dominguez TE, Pollock AN, Niles D, Meyer A, Myklebust H, et al. Estimation of optimal CPR chest compression depth in children by using computer tomography. Pediatrics. Jul 2009;124(1):e69-74. 4.Christman C, Hemway RJ, Wyckoff MH, Perlman JM. The two-thumb is superior to the two-finger method for administering chest compressions in a manikin model of neonatal resuscitation. Archives of disease in childhood. Fetal and neonatal edition. Mar 2011;96(2):F99-F101. 5.Clements F, McGowan J. Finger position for chest compressions in cardiac arrest in infants.Resuscitation. Mar 2000;(1):43-46. 6.Dannevig I, Solevag AL, Saugstad OD, Nakstad B. Lung Injury in Asphyxiated Newborn Pigs Resuscitated from Cardiac Arrest - The Impact of Supplementary Oxygen, Longer Ventilation Intervals and Chest Compressions at Different Compression-toVentilation Ratios. The open respiratory medicine journal. 2012;6:89-96. 7.Dannevig I, Solevag AL, Sonerud T, Saugstad OD, Nakstad B. Brain inflammation induced by severe asphyxia in newborn pigs and the impact of alternative resuscitation strategies on the newborn central nervous system. Pediatric research. Feb 2013;73(2):163-170. 8.Dannevig I, Solevag AL, Wyckoff M, Saugstad OD, Nakstad B. Delayed onset of cardiac compressions in cardiopulmonary resuscitation of newborn pigs with asphyctic cardiac arrest. Neonatology. 2011;99(2):153-162. 9.David R. Closed chest cardiac massage in the newborn infant. Pediatrics. Apr 1988;81(4):552-554. 10.Dorfsman ML, Menegazzi JJ, Wadas RJ, Auble TE. Two-thumb vs. two-finger chest compression in an infant model of prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Oct 2000;7(10):1077-1082. References 11.Ewy GA. Continuous-chest-compression cardiopulmonary resuscitation for cardiac arrest. Circulation. Dec 18 2007;116(25):2894-2896. 12.Ewy GA, Zuercher M, Hilwig RW, Sanders AB, Berg RA, Otto CW, et al. Improved neurological outcome with continuous chest compressions compared with 30:2 compressions-to-ventilations cardiopulmonary resuscitation in a realistic swine model of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Circulation. Nov 27 2007;116(22):2525-2530. 13.Haque IU, Udassi JP, Udassi S, Theriaque DW, Shuster JJ, Zaritsky AL. Chest compression quality and rescuer fatigue with increased compression to ventilation ratio during single rescuer pediatric CPR. Resuscitation. Oct 2008;79(1):82-89. 14.Hemway RJ, Christman C, Perlman J. The 3:1 is superior to a 15:2 ratio in a newborn manikin model in terms of quality of chest compressions and number of ventilations. Archives of disease in childhood. Fetal and neonatal edition. Jan 2013;98(1):F42-45. 15.Houri PK, Frank LR, Menegazzi JJ, Taylor R. A randomized, controlled trial of two-thumb vs two-finger chest compression in a swine infant model of cardiac arrest [see comment]. Prehospital emergency care : official journal of the National Association of EMS Physicians and the National Association of State EMS Directors. Apr-Jun 1997;1(2):65-67. 16.Huynh T, Hemway RJ, Perlman JM. Assessment of effective face mask ventilation is compromised during synchronised chest compressions. Arch Dis Child-Fetal. Jan 2015;100(1):F39-F42. 17.Huynh TK, Hemway RJ, Perlman JM. The two-thumb technique using an elevated surface is preferable for teaching infant cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The Journal of pediatrics. Oct 2012;161(4):658-661. 18.Kapadia V, Wyckoff MH. Chest compressions for bradycardia or asystole in neonates. Clinics in perinatology. Dec 2012;39(4):833-842. 19.Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, Aziz K, Colby C, Fairchild K, Gallagher J, et al. Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Pediatrics. Nov 2010;126(5):e1400-1413. References 20.Kern KB, Hilwig RW, Berg RA, Sanders AB, Ewy GA. Importance of continuous chest compressions during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: improved outcome during a simulated single lay-rescuer scenario. Circulation. Feb 5 2002;105(5):645-649. 21.Lee KH, Kim EY, Park DH, Kim JE, Choi HY, Cho J, et al. Evaluation of the 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for infant CPR finger/thumb positions for chest compression: a study using computed tomography. Resuscitation. Jun 2013;84(6):766-769. 22.Lee SH, Cho YC, Ryu S, Lee JW, Kim SW, Yoo IS, et al. A comparison of the area of chest compression by the superimposed-thumb and the alongside-thumb techniques for infant cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. Sep 2011;82(9):1214-1217. 23.Li ES, Cheung PY, O'Reilly M, Aziz K, Schmolzer GM. Rescuer fatigue during simulated neonatal cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. Feb 2015;35(2):142-145. 24.Lim JS, Cho Y, Ryu S, Lee JW, Kim S, Yoo IS, et al. Comparison of overlapping (OP) and adjacent thumb positions (AP) for cardiac compressions using the encircling method in infants. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. Feb 2013;30(2):139-142. 25.Martin P, Theobald P, Kemp A, Maguire S, Maconochie I, Jones M. Real-time feedback can improve infant manikin cardiopulmonary resuscitation by up to 79%--a randomised controlled trial. Resuscitation. Aug 2013;84(8):1125-1130. 26.Martin PS, Kemp AM, Theobald PS, Maguire SA, Jones MD. Does a more "physiological" infant manikin design effect chest compression quality and create a potential for thoracic over-compression during simulated infant CPR? Resuscitation. May 2013;84(5):666-671. 27.Menegazzi JJ, Auble TE, Nicklas KA, Hosack GM, Rack L, Goode JS. Two-thumb versus two-finger chest compression during CRP in a swine infant model of cardiac arrest. Annals of emergency medicine. Feb 1993;22(2):240-243. 28.Meyer A, Nadkarni V, Pollock A, Babbs C, Nishisaki A, Braga M, et al. Evaluation of the Neonatal Resuscitation Program's recommended chest compression depth using computerized tomography imaging. Resuscitation. May 2010;81(5):544-548. 29.Mildenhall LFJ, Huynh TK. Factors modulating effective chest compressions in the neonatal period. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 12// 2013;18(6):352-356. References 30.Moya F, James LS, Burnard ED, Hanks EC. Cardiac massage in the newborn infant through the intact chest. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. Sep 15 1962;84:798-803. 31.Orlowski JP. Optimum position for external cardiac compression in infants and young children. Annals of emergency medicine. Jun 1986;15(6):667-673. 32.Phillips GW, Zideman DA. Relation of infant heart to sternum: its significance in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Lancet. May 3 1986;1(8488):1024-1025. 33.Saini SS, Gupta N, Kumar P, Bhalla AK, Kaur H. A comparison of two-fingers technique and two-thumbs encircling hands technique of chest compression in neonates. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. Sep 2012;32(9):690-694. 34.Schmolzer GM, Kumar M, Aziz K, Pichler G, O'Reilly M, Lista G, et al. Sustained inflation versus positive pressure ventilation at birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of disease in childhood. Fetal and neonatal edition. Jul 2015;100(4):F361-368. 35.Schmolzer GM, O'Reilly M, Labossiere J, Lee TF, Cowan S, Nicoll J, et al. 3:1 compression to ventilation ratio versus continuous chest compression with asynchronous ventilation in a porcine model of neonatal resuscitation. Resuscitation. Feb 2014;85(2):270-275. 36.Schmolzer GM, O'Reilly M, Labossiere J, Lee TF, Cowan S, Qin S, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation with chest compressions during sustained inflations: a new technique of neonatal resuscitation that improves recovery and survival in a neonatal porcine model. Circulation. Dec 3 2013;128(23):2495-2503. 37.Solevag AL, Cheung PY, Li E, Aziz K, O'Reilly M, Fu B, et al. Quantifying force application to a newborn manikin during simulated cardiopulmonary resuscitation. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstet. Jul 29 2015:1-3. References 38.Solevag AL, Cheung PY, Lie H, O'Reilly M, Aziz K, Nakstad B, et al. Chest compressions in newborn animal models: A review. Resuscitation. Aug 19 2015;96:151-155. 39.Solevag AL, Dannevig I, Wyckoff M, Saugstad OD, Nakstad B. Extended series of cardiac compressions during CPR in a swine model of perinatal asphyxia. Resuscitation. Nov 2010;81(11):1571-1576. 40.Solevag AL, Dannevig I, Wyckoff M, Saugstad OD, Nakstad B. Return of spontaneous circulation with a compression:ventilation ratio of 15:2 versus 3:1 in newborn pigs with cardiac arrest due to asphyxia. Archives of disease in childhood. Fetal and neonatal edition. Nov 2011;96(6):F417-421. 41.Solevag AL, Madland JM, Gjaerum E, Nakstad B. Minute ventilation at different compression to ventilation ratios, different ventilation rates, and continuous chest compressions with asynchronous ventilation in a newborn manikin. Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergency medicine. 2012;20:73. 42.Thaler MM, Stobie GH. An Improved Technic of External Cardiac Compression in Infants and Young Children. The New England journal of medicine. Sep 19 1963;269:606-610. 43.Tingay DG, Bhatia R, Schmolzer GM, Wallace MJ, Zahra VA, Davis PG. Effect of sustained inflation vs. stepwise PEEP strategy at birth on gas exchange and lung mechanics in preterm lambs. Pediatric research. Feb 2014;75(2):288-294. 44.Todres ID, Rogers MC. Methods of external cardiac massage in the newborn infant. The Journal of pediatrics. May 1975;86(5):781-782. 45.Udassi JP, Udassi S, Lamb MA, Lamb KE, Theriaque DW, Shuster JJ, et al. Improved chest recoil using an adhesive glove device for active compression-decompression CPR in a pediatric manikin model. Resuscitation. Oct 2009;80(10):1158-1163. 46. Udassi JP, Udassi S, Theriaque DW, Shuster JJ, Zaritsky AL, Haque IU. Effect of alternative chest compression techniques in infant and child on rescuer performance. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. May 2009;10(3):328-333. 47. You Y. Optimum location for chest compressions during two-rescuer infant cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation. Dec 2009;80(12):1378-1381.