Eminent Domain and Takings Law - The Workforce Housing Council

advertisement

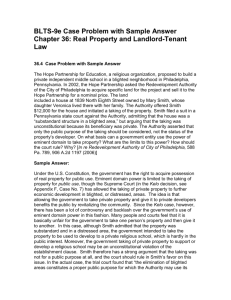

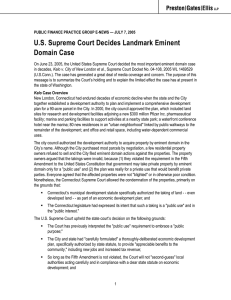

Eminent Domain and Takings Law: Federal and Northern New England Perspectives Friday – June 13, 2008 Benjamin Frost, Esq, AICP 1 You know there’s a problem when… 2 3 Municipalities’ Power • Local control? That may be a desire, but our three states are Dillon’s Rule states • Agents of the sovereign • Must look to statutes for authority to do anything • Statutory eminent domain authority for municipalities to do a variety of things 4 Source of Eminent Domain Power • An inherent power of the sovereign • Cannot be surrendered or taken away • But the sovereign itself can impose limits 5 Constitutional Limitations • US and state Constitutions restrict the power of the sovereign to take property • Require “public use” and “just compensation” King John signing the Magna Carta, 1215 6 U.S. Constitution, Amendment V No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation. 7 NH Constitution, Part 1, Article 12 [Art.] 12. [Protection and Taxation Reciprocal.] Every member of the community has a right to be protected by it, in the enjoyment of his life, liberty, and property; he is therefore bound to contribute his share in the expense of such protection, and to yield his personal service when necessary. But no part of a man’s property shall be taken from him, or applied to public uses, without his own consent, or that of the representative body of the people. Nor are the inhabitants of this state controllable by any other laws than those to which they, or their representative body, have given their consent. 8 VT Constitution, Ch. 1, Article 2 “That private property ought to be subservient to public uses when necessity requires it, nevertheless, whenever any person’s property is taken for the use of the public, the owner ought to receive an equivalent in money.” 9 ME Constitution, Art. 1, Sec. 21 “Private property shall not be taken for public uses without just compensation; nor unless the public exigencies require it.” 10 A Fair and Balanced View of Kelo 11 1 6 5B 5A 2 3 5C 4A Fort Trumbull State Park 4B 7 Pfizer Site 12 Susette Kelo… …and her cute cottage. 13 What Does “Public Use” Mean? The Kelo Court’s Polar Propositions 1. “[T]he sovereign may not take the property of A for the sole purpose of transferring the it to another private party B, even though A is paid just compensation.” 2. [A] State may transfer property from one party to another if future “use by the public is the purpose of the taking…” 14 Public Use(s) • “Use by the public” requirement was rejected long ago by federal and state courts: “…proved impractical given the diverse and always evolving needs of society.” • Apply the “more natural interpretation” of public purpose. • What did Kelo really change? 15 Public Purpose Berman v. Parker (1954) • 5,000 DC housing units, mostly beyond repair • Most of condemned land to be used for public facilities • Petitioner’s thriving department store also targeted • Unanimous court: deferred to legislative judgment that planning must be done as a whole; “community redevelopment programs need not, by force of the Constitution, be on a piecemeal basis—lot by lot, building by building.” 16 Public Purpose Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff (1984) • Property taken from lessors and transferred mostly to long-term lessees. • A to B private-private transfer? • No—intended to end long-standing feudal ownership system (land oligopoly)—a valid public purpose 17 The New London Situation • A carefully formulated economic development plan that will afford community-wide benefits • State statutory authority • Limited scope of federal review • Appropriate to “resolve the challenges of the individual owners, not on a piecemeal basis, but rather in light of the entire plan.” 18 The Conclusion • Court finds no basis for exempting economic development from historically broad understanding of “public purpose” • Court declines to second-guess the City’s determination of what properties need to be acquired 19 Kelo Court’s Invitation • “…nothing in our opinion precludes any State from placing further restrictions on its exercise of the takings power.” • Constitutional provisions: e.g., Michigan • Statutory provisions: e.g., California 20 New Hampshire Pre-Kelo • Merrill v. City of Manchester (1985) • “Public use” subject to a balancing test: “The net benefit to the public will consist of the benefits of the proposed project and the benefits of the eradication of any harmful characteristics of the property in its present form, reduced by the social costs of the loss of the property in its present form.” 21 New Hampshire Pre-Kelo • Merrill – Undeveloped land in Current Use (RSA 79-A) – Proposed to be taken for an industrial park – Clear legislative purpose: social value in undeveloped land— “open space” – Such land may only be taken for direct public use— school, playground, utilities—and not for uses with incidental public benefits • Could a Kelo-like taking have occurred under Merrill? 22 New Hampshire Post-Kelo • No cases, but lots of activity in the Legislature • Chapter 234, Laws of 2006 • “Public use” clarified – Precludes takings solely for facilitating “incidental private use.” – Excludes public benefits from private economic development, “including increased tax revenues and increased employment opportunities.” 23 New Hampshire Post-Kelo • 2006 Constitutional Amendment • Part I, Art. 12-a [Power to Take Property Limited.] No part of a person's property shall be taken by eminent domain and transferred, directly or indirectly, to another person if the taking is for the purpose of private development or other private use of the property. Adopted November 7, 2006 • What about the balancing test? 24 Vermont Pre-Kelo 85 VSA § 3210. Eminent domain; authority; survey. (a) A municipality shall have the right to acquire by condemnation a fee simple title or any other interest in real property which it may determine necessary for or in connection with an urban renewal project under this chapter. The powers conferred upon municipalities under this section shall be considered "urban renewal project powers" as defined in section 3219(b) of this title and the term "municipality", as used in this section, shall mean the agency, board, commissioner or officers having such powers under section 3219(a) of this title. The municipality shall set out the necessary lands and cause them to be surveyed. An urban renewal plan approved under section 3207(d) of this title may be considered to constitute such a survey. 25 Amended 1963, No. 2, § 3, eff. Feb. 14, 1963; 1964, No. 9 (Sp. Sess.), § 1, eff. March 5, 1964. Vermont Post-Kelo 12 VSA § 1040 (a) Notwithstanding any other provision of law, no governmental or private entity may take private property through the use of eminent domain if the taking is primarily for purposes of economic development, unless the property is taken pursuant to chapter 85 of Title 24 (urban renewal) (b) This section shall not affect the authority of an entity authorized by law to use eminent domain for the following purposes: (1) transportation projects, including highways, airports, and railroads; (2) public utilities, including entities engaged in the generation, transmission, or distribution of electric, gas, sewer and sewage treatment, or communication services; (3) public property, buildings, hospitals, and parks; or (4) water, wastewater, stormwater, flood control, drainage, or waste disposal projects. Added 2005, No. 111 (Adj. Sess.), § 1. 26 Maine Post-Kelo 1 MRSA § 816. Limitations on eminent domain authority 1. Purposes. Except as provided in subsections 2 and 3 and notwithstanding any other provision of law, the State, a political subdivision of the State and any other entity with eminent domain authority may not condemn land used for agriculture, fishing or forestry or land improved with residential homes, commercial or industrial buildings or other structures: A. For the purposes of private retail, office, commercial, industrial or residential development; B. Primarily for the enhancement of tax revenue; or C. For transfer to an individual or a for-profit business entity. 27 Just Compensation • Fair Market Value Measurement – Most probable price on the open market – Determined three ways: comparable sales, income, replacement cost – Should be based on the “best and highest” use of the property • Highest market value, greatest financial return, most profit • Should represent a reasonably probable use 28 NH Eminent Domain Procedure Act • Since 1971, New Hampshire law governing all condemnations of property for public use • Not an expansion or limitation of the rights of condemnees or condemnors – Merely established a consistent process for eminent domain 29 NH Eminent Domain Procedure Act • • • • Appraisal and Notice of Offer Declaration of Taking; Recording of Notice Condemnee’s Options Appeals 30 Inverse Condemnation—Federal • Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon (1922) – “…while property may be regulated to a certain extent, if regulation goes too far it will be recognized as a taking.” – How far is “too far”? • Lucas v. So. Carolina Coastal Council (1992) – A compensable taking will occur if a regulation denies “all economically beneficial and productive use of the land.” – Conversely, if a reasonable, economically beneficial and productive use of the land remains that is not prohibited by regulation, then a taking has not occurred. 31 Inverse Condemnation—States • NH, ME, and VT law is similar: reasonable regulations will generally be upheld. • What’s reasonable? – Limitation of owner’s use to protect others from harm or loss of use of their own land – But excessive action will trigger compensation 32 Misinterpretation and Delay • Delay in permitting is generally not compensable—it is a cost of doing business, part of the land development process • Errors in interpreting a valid regulation also not compensable • Distinguish from an invalid ordinance • Development moratoria do not require compensation in the abstract (Tahoe-Sierra, 535 U.S. 302 (2002)). 33 Questions? Ben Frost bfrost@nhhfa.org (603) 310-9361 34