Shinto

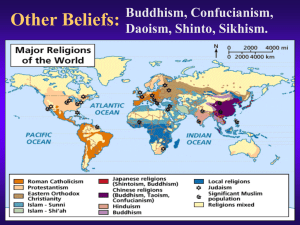

advertisement

Shinto Summary: Shinto, a loosely organized native Japanese religion, embraces a wide variety of beliefs and practices. The variety is so wide that it is difficult to define Shinto precisely. In one sense, Shinto is a religious form of Japanese nationalism. Its mythology describes the formation of Japan as a land that is superior to all other lands; its shrines commemorate the great heroes and events in the history of Japan. Historically, it has taught the Japanese people that their emperors were descendants of the sun goddess. Western commentators have frequently compared Japanese Shinto to the feeling that Americans get when visiting Gettysburg or the Washington Monument. Perhaps the closest comparison would be what takes place in some American towns on Memorial Day, when people recall great events in national history, visit the graves of war dead, and ask God to bless the nation on a beautiful late spring day. Shinto is more than religious nationalism, however. It also involves the Japanese in a worshipful attitude toward the beauties of their land, particularly its mountains and forests. It includes aspects of animism and ancestor worship. Large-scale, public Shinto rituals take place in shrines throughout Japan. Private family rituals are carried out in small shrines in Japanese homes. Highly organized and active religious sects also have developed from basic Shinto. Thus, the term “Shinto” may refer to a multitude of varying Japanese religious and cultural practices. The word “Shinto” itself was not officially coined until the 6th century C.E., to distinguish native Japanese religion from the newer religions/philosophies—Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism—being imported from China and Korea during the period. The word Shinto actually comes from the Chinese words shen and tao, which may be roughly translated in this context as “the way of the gods.” The preferred Japanese term that describes this native religion is kami-no-michi, which also may be defined as “the way of the gods.” A Timeline of Shinto 522 The term “Shinto” is used to distinguish Buddhism from local religion 8th c. Composition of Shinto classics 800-1700 Shinto is combined with other religions 1700 Revival of the ancient tradition 1868 Meji state religion 1887 Buddhism is allowed 1889 Religious freedom 1946 State Shinto is abolished Japanese Mythology: To understand Japanese religion before the sixth century C.E., we must look at some of the traditional myths surrounding the origin of Japan, its native gods, and its early history. In the beginning, there were the kami, usually defined as “gods,” which is inexact. Some scholars have chosen to define kami as mana, which indicates “the occult force that preliterate man found emanating from objects and experiences that aroused in him emotions of wonder and awe.” Others have identified kami with the Greek term daimon, but that is also lacking. Even 18th century Japanese Shinto scholar Motoori Norinaga confessed, “I do not yet understand the meaning of the term kami.” Kami certainly refers to the deities of heaven and earth worshipped by the Japanese people, but it can also refer to the spirit that is in human beings, animals, trees, plants, seas, and mountains. Any person, thing, or force that possessed superior power or was awesome in any way was described by the ancient Japanese as kami. Although kami may be defined in these broad terms, in mythology it generally refers to gods or to humans with godlike powers. The major source for our knowledge of Japanese mythology is the Kojiki, “Chronicles of Ancient Events,” collected in the 7th and 8th centuries C.E. as a response to the entrance of Chinese culture and religions. In these centuries, the Japanese, although willing to accept the advanced culture of the Chinese, sought their own heritage. The results of this search yielded the chronicles, which contain a section called “The Age of the Gods,” the mythological background of Japanese culture. The Kojiki includes stories that describe the special creation of the Japanese islands by two kami, Izanagi and his consort, Izanami. These two became the divine parents of the other kami in Japanese mythology. The chief of these spirits is Amaterasu, the sun goddess. All of the Japanese emperors are believed to have descended from the line of Amaterasu. The History of Shinto According to mythological tradition, the first Japanese emperor was enthroned in the seventh century B.C.E., but most modern scholars agree that the actual history of Japan does not begin until the third century C.E. At that point, Japan became known to other nations and began to keep historical records. Therefore, Japan’s is among the youngest cultures of all of the Asian nations. Early in its history, Japan became an object of interest to Chinese and Korean merchants and missionaries, who brought with them much of the older culture of China, including its arts, language, system of writing, and, of course, its various religions and ethical systems. After the fourth century C.E., Japan came under the influence of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism. All of these had a lasting effect on Japanese civilization. The Kojiki records the entrance of Chinese culture into Japan. Before this period, the Japanese had no written language. They subsequently adopted the Chinese script and many other elements of Chinese culture. Confucian ethics were welcomed because Japan was governed by a feudal system, and Confucianism provided an ethical foundation for the Japanese political system. Ancestor worship had always been practiced in Japan; thus, Confucian and Taoist elements that emphasized filial piety were readily accepted. The Chinese arts, particularly those connected to Buddhist ritual, were also adopted. Altogether, the period between the fourth and eighth centuries C.E. was one of dramatic change for Japan. According to the Japanese chronicles, the emperor was presented with an image of the Buddha and several volumes of Buddhist scripture in 522 C.E. The emperor was delighted, but his advisers warned him that the introduction of a foreign god might arouse the anger of the native kami. Shortly after the introduction of the Buddha, a plague broke out in Japan. Afraid that the plague was the work of vengeful kami, the emperor had the Buddha image thrown into a canal and the temple built to house it burned. The chronicles explain that the emperor’s rejection of the foreign religion brought the plague to an end. In succeeding generations, however, other statues of the Buddha were introduced into Japan, as well as prayers and rituals. By the end of the sixth century C.E., Mahayana Buddhism had taken a firm foothold in Japan. Japanese reaction to Buddhism was four-fold. First was the introduction of the name Shinto or kami-no-michi to distinguish the native Japanese religion from the new foreign religion. Second, Japanese advocates of Shinto recognized the many Buddhas and Bodhisattvas of Buddhism, but thought of them as the revelation of the kami to the Indian and Chinese people. Naturally, the Buddhists tended to reverse this line of thinking and to identify the kami as Japanese revelations of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. The third reaction was Ryobu (Two Aspect Shinto), a syncretism between Shinto and Buddhism that developed in Japan between the sixth and ninth centuries C.E. Little by little, the boundaries between the two religions disappeared. Buddhist priests began to officiate at Shinto shrines. Buddhist architectural elements were added to Shinto temples. Generally, Japanese life began to be divided into two spheres. The concerns of day-to-day life became the domain of the Shinto side of the religion, and concerns for the afterlife were served by the Buddhists. Thus, a traditional citizen of Japan might be said to have been born a Shintoist but to have died a Buddhist. For ten centuries, Shinto and Buddhism lived side by side in Japan, each serving a special need of the people. The fourth reaction of the Japanese to Buddhism was the development of some distinctively Japanese forms of Buddhism. Mahayana Buddhism is an extremely elastic religion, allowing for variations to such a degree that it may be considered a family of religions rather than a single branch of Buddhism. Buddhism had emphasized meditation as a means of insight into religious truth. The Chinese Buddhists had picked up this emphasis through the missionary work of Bodhidharma and called it their branch of Buddhism Ch’an. The Japanese developed meditative Mahayana Buddhism even further under the name Zen. The Japanese also originated or developed other forms of Buddhism, such as Pure Land and Nichiren. These and other forms of Buddhism became so popular in Japan that even though Shinto was intermingled with them, it was almost forgotten as a viable religion for the people of Japan. Many reformers wished to revise and revitalize the native religion of Japan. As early as the fourteenth century, various scholars tried to point out the strengths of Shinto and restore it to a place of prominence. However, it was not until the seventeenth century and the rise of the Tokugawa regime (1600-1867) that Shinto received official support. In this era, the Japanese were unified by tough-minded military leaders who sought to isolate the nation from outside influences. Because Buddhism and Christianity were foreign-born, they were pushed aside; since Shinto was native to Japan, it was given new strength and support by the national government. Large numbers of Christians were executed when they refused to renounce their faith. A Japanese version of Confucianism was the only foreign system that was allowed support during this period, because Confucian ethics were supportive of the militaristic Tokugawa regime. One of the most colorful aspects of Japanese life during the Tokugawa era was the feudal knight, called samurai. Throughout the history of Japan, individual warriors hired themselves out as bodyguards or mercenary soldiers to lords; but in the Tokugawa era, the samurai was idealized and a code of conduct was established for him. In the seventeenth century, the government set up the Chu His (Shushi) School of Confucianism as the orthodox model for the conduct of the upper classes. A leader of this school, Yamaga Soko (1622-1685) led in combining Shinto and Confucianism to develop the warrior code called Bushido, “the way of the fighting knight.” The standard of conduct established for the Japanese feudal knight was similar in many respects to that of the idealized Christian knight of medieval Europe, except for the absence of romantic love. Generally, Bushido required that a samurai be loyal to his master in the hierarchy of the feudal system; must have great courage in life, in battle, and in his willingness to lay down his life for his master; must be a man of honor; and must be a gentleman in every sense of the word, polite to his master and to people in positions of authority as well as benevolent toward peasants, righting wrongs and bringing justice to victims of injustice. The willingness of the proper samurai to commit suicide rather than face dishonor and the attitude of the Japanese people toward suicide as a whole have long amazed Westerners. Many European religious traditions forbid suicide. In Japan, however, suicide has often been encouraged as a means of avoiding dishonor, as a means of escaping a bad situation, as a means of protest, and in World War II as a very effective means of destroying enemy warships. Perhaps no other culture in the history of this world has had this attitude toward suicide. In Bushido, the warrior is expected to kill himself in a slow, painful manner called seppuku. (Westerners prefer the term hara-kiri, which means “belly slitting”). This is suicide by disembowelment. At the proper time, the warrior is expected to slit open his abdomen so his intestines fall out. In more recent times, it became common for a friend to chop off the head right after the necessary slitting took place. This form of death was reserved for warriors and nobility. Women and peasants were forbidden to commit seppuku and were expected to kill themselves in a quicker manner by stabbing themselves in the throat. The willingness of warriors to die in such a manner for personal honor or for the good of the Japanese nation may seem out of place to the Westerner trained in the sacredness of life and the evils of suicide, but in the coming together of the Shinto’s love of and worship for the nation and its heroic figures and the Confucian’s high sense of honor, seppuku is considered very religious. During the Tokugawa era, Japan did its best to avoid foreign influence in any form. It closed itself off from foreign trade, diplomatic missions, and foreign religions. During this period, it attempted to draw only from its native resources. In 1853, Japan was brought to a sudden confrontation with the outside world when Commodore Perry of the U.S. Navy appeared in Tokyo Bay and asked that the Japanese ports be opened and trade relations established between the United States and Japan. In 1854, Perry appeared again with more ships, troops, and cannons; the Japanese rulers were forced to open their nation to foreigners. After a period of some confusion over what role religion was to play in the new Japan, it was decided, in the Constitution of 1889, that the nation would follow the pattern of many Western nations in that there would be state-supported religion but that all other religions would be allowed to exist and propagate. There would be state-supported Shinto that would essentially consist of patriotic rituals at certain shrines. The state took over the support of some 110,000 Shinto shrines and approximately 16,000 priests who tended these shrines throughout the nation. Each shrine supported by the state was dedicated to some local deity, hero, or event; the grand imperial shrine at Ise was dedicated to the mother goddess of Japan, Amaterasu. The visitor approaches the shrine through a distinctive Japanese archway, called a torii, which is so inseparably connected to Shinto that it was become known worldwide as its symbol. The typical major shrine consists of two buildings, an inner and an outer shrine. Both are built of unpainted wood and must be torn down and rebuilt once every twenty years. Anyone may visit the outer shrine, but the inner one is reserved for priests and government officials. The inner shrine contains objects of importance to the deity or event it commemorates. For example, at the grand imperial shrine, the sacred objects are a mirror, sword, and string of beads, all of which are important to the myth of Amaterasu. On certain occasions or holidays, these relics are publicly displayed. With the developments of the Meiji era (1868-1912), specifically when the government treated Shinto as a nationalistic and militaristic institution, the religious side of Shinto was forced to identify itself separately and find its own support, as were all other religions in Japan. The adherents of these religions are thought to number more than 18 million; however, statistics regarding any religion are always suspect, and this is especially true in Japan, where a person may in good conscience be a Buddhist, a Confucian, and a member of a Shinto sect all at the same time). The thirteen major sects of Shinto may be divided into three categories. First are the sects whose primary emphasis is on mountain worship. The beautiful, graceful mountains of Japan have always been objects of reverence to its people. At some point, it became popular for people to climb the mountains during seasonal pilgrimages. A second category developed from the basic practices of shamanism and divination of the Japanese peasants. The basic appeal of these sects in modern Japan is their promise of faith healing. A third type includes sects classified as more or less pure Shinto. When the rulers took over the shrines of Shinto in the Meiji era and used them for political purposes, this left behind a basic residue of the religious tradition of Shinto, its mythology, and its rituals. Three major sects developed to emphasize these religious elements and revived the myths of the origin of Japan from the ancient chronicles. They emphasized purification of the body through fasting, breath control, bathing in cold water, chanting, and many other devices similar to those of the Yoga cults of Hinduism. Today, these sects seem to be losing ground among the people of Japan. In addition to the organized forms of state and sectarian Shinto is another, more basic form. This is the very simple and common form of Shinto that takes place in many Japanese homes. The basic unit or symbol of domestic Shinto is the kami-dana (god shelf), which is found in many Japanese homes, containing the symbols of whatever may be of religious significance to the family. It usually contains the names of the ancestors of the family, because a part of the religion of the household is filial piety. It might contain statues of the gods that have been beneficial to the family or are highly regarded. In the homes and shops of many Japanese artisans are the images of the various patron deities. The literature of Japan contains many stories of skilled workers creating masterpieces under the direction of an unseen patron god. The traditional kami-dana contains objects that have been bought at the great shrines, such as the one at Ise. Any object the family considers sacred is fit for veneration at the god shelf. There is a story that the kami-dana in one household contained the cast-off shoes of a man who had been a benefactor of the household when it was in trouble. The shoes were believed to be symbolic of the friend’s goodness or to contain the mana or kami that prompted the good deeds. At any rate, they became objects of veneration. Worship at the kami-dana in the Japanese home is a simple affair. Offerings of flowers, lanterns, incense, food, and drink may be placed before this altar each day. A simply daily service in which the worshippers wash their hands, make an offering, clap their hands as a symbol of communication with the spirits, and offer a brief prayer may also be held here. On such special occasions as holidays, weddings, or anniversaries, more elaborate ceremonies may be held at the kami-dana. However, if the occasion is decidedly religious—a funeral, for example—the Japanese family turns not to the Shinto deities or priest but to the Buddhist priest. In the special religious syncretism of Japan, Shinto is for this life but Buddhism is for the life beyond. Therefore, in addition to their kami-dana, many Japanese homes have a butsu-dan, a Buddhist household altar, where worship of the Buddhist deities is also held. Traditional Japanese holidays are a combination of secular, agricultural, Buddhist, and Shinto celebrations. At times, one tradition or religion dominates; at others, all others blend together. Various festivals are held at local Shinto shrines throughout the year. These include the Japanese New Year. New Year used to be held in February when a lunar calendar was followed; today, it is celebrated January 1 through January 6. During this period, businesses close and people gather with their families, purifying and cleaning the home for the New Year. On New Year’s Eve, special food is eaten and offerings are made to the ancestors. At Buddhist temples at midnight, gongs are struck 108 times for 108 kinds of passion to be purged in the coming year. On New Year’s Day, families visit places of worship: some to Buddhist temples, but most to Shinto shrines. At the end of the season, New Year’s decorations are burned in bonfires. On April 8, Japan celebrates Buddha’s birthday. At Buddhist temples, priests pour flowers and sweet tea over the statues of the Buddha as a remembrance that on the day of his birth flowers and sweet tea came down from heaven. December 8 is celebrated as the traditional day of Buddha’s enlightenment. Zen Buddhists participate in an all-night meditation to welcome this day. Among Japanese Buddhists, Ulllambana (the festival for dead ancestors, or All Soul’s Day), is celebrated in midJuly. As in other Buddhist nations, this holiday is an occasion to welcome the spirits of the dead into homes. In this season, graves are swept and decorated. It also is at time of parades, dancing, and bonfires. A combination agricultural and Shinto holiday is Niiname-sai, celebrated on November 23 and 24. At this autumn festival, the emperor offers the first fruits of the autumn harvest to Amaterasu and the other kami at Ise. Although this is the national festival of the harvest, various local thanksgiving ceremonies are held throughout Japan during October and November. Following the defeat of Japan at the end of World War II, several events occurred that made the future of Shinto uncertain. The most direct threat to this religion was the removal of official government support for state Shinto. State Shinto was established to engender patriotism and loyalty toward the nation of Japan. The Constitution of 1889 began with these words: “The Empire of Japan shall be reigned over and governed by a line of Emperors unbroken for ages eternal…The Emperor is sacred and inviolable.” This constitution also made the military leaders responsible to the emperor rather than to the parliament. State Shinto therefore became an instrument of support for the military in the wars in which Japan participated during the last part of the 19th and first part of the 20th centuries. It was particularly supportive of the Japanese war effort during WWII. Shinto had become such an inseparable part of Japanese militarism that they American occupation forces felt it necessary to abolish state support for Shinto in December 1945. In January 1946, the occupation forces directed the emperor to issue a statement declaring that he was not divine. Since 1945, the shrines once supported by the Japanese government have continued to exist but are now sustained by the financial support of private citizens. Immediately following World War II, attendance at these shrines dropped off and many fell into disuse. In Japan’s remarkably fast industrialization post-WWII, Shinto competed with not only it own antiquity against the modern world, but also its old rival, Buddhism. Most Japanese today consider themselves Buddhists primarily, with Shinto viewed as a secondary practice. One might think that Shinto, with its ancient myths, rituals, and shrines, would quickly fade away, but it remains strong in Japan today, with interest in the shrines reviving, and new sects emphasizing faith healing, positive thinking and chanting being accepted by millions of Japanese. Adherents of the some of these new sects have entered politics and supported certain labor unions; new forms of Shinto have also provided an outlet for the day-to-day stresses of the urban population in modern Japan. In its many forms, Shinto remains an important force in Japanese culture.