Selective Mutism

advertisement

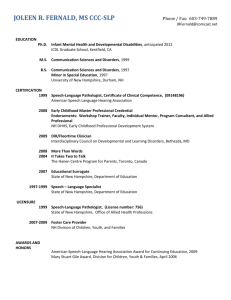

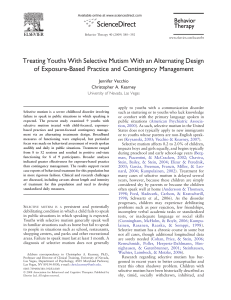

Selective Mutism in Children: A Psychogenic Voice Disorder Emily Buchanan April 1, 2003 Definition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders The persistent refusal to talk in one or more social situations, including school Consistent failure to speak in specific social situations in which there is an expectation for speaking (e.g., school), despite speaking in other situations The disturbance interferes with educational or occupational achievement or with social communications The duration of the disturbance is at least 1 month (not limited to the first month of school) Failure to speak is not limited to lack of knowledge or comfort with social language required (e.g., bilingual or immigrant children) (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) Symptoms: Excessive shyness Fear of social embarrassment Social isolation Withdrawal Impulsive traits Negativism Clinging behavior Temper tantrums Controlling or oppositional behaviors Theories of causation Immigrant family background Significant early childhood trauma Injury that affects the mouth Possible family secrets Anxiety is most commonly an underlying feature! Problems of Selective Mutism Provides limited opportunity for social interaction and growth Delays the development of appropriate oral reading and work attack skills Hinders the involvement in normal school activities Prevalence Estimated to occur in less than .8 per 1,000 of the population Slightly more common in females than males Onset is usually before 5 years Many times disturbances may not come into attention until entry into school One or both parents of a selectively mute child have a history of anxiety symptoms, including shyness, social anxiety, or panic attacks Suggests the child’s anxiety is a familial trend! (Giddan et. Al, 1997) History Previously called elective mutism, renamed in 1987 Covers broad spectrum from psychoanalytic schools of Europe in 1800s to contemporary behavioral interventions In early German literature, selectively mute children were removed from the home and place in residential treatment centers A Norway study by Wergeland (1979) described selectively mute children who were removed from their homes from 8 months to 3 years Found that untreated children were better at follow-up than the children who had been removed from their homes (Giddan et. Al, 1997) History con’t Little attention paid to associated speech and language problems in children with selective mutism until Baltaxe (1994) who examined 12 years of records at the UCLA Neuropsychiatric Institute: Of the 24 patients identified: 75% had articulation problems 86% failed auditory processing measures 60% demonstrated receptive language problems 75% showed expressive deficits (Baltaxe, 1994) Psychoanalytic View Psychoanalysts: children who are orally fixated wish to punish their parents They may be maintaining a family secret, displacing hostility toward the mother, or regressing to a preverbal stage Atoynatan (1986) believed the mutism was a vehicle for the mother’s unexpressed hostility Through it, the child achieves an exclusive relationship with the mother (Atoynatan, 1986) Behavioral View Selective mutism is the product of a long series of negatively reinforced learning patterns Approaches reduce anxiety about talking and/or reinforcing the child for speaking (Giddan et. Al, 1997) SLP roles in Selective Mutism Communication and Linguistic specialist Often the first consulted when a child is not talking in school Coordinate efforts of a multidisciplinary team Psychologist, psychotherapist, social worker, classroom teacher, special education teacher, parents, peers Important contributors to the programs designed for the child Education for other professionals, teachers, parents/family Help the teacher develop different methods of assessment of the child’s reading abilities Advocate/Confidant for the child Diagnosing SLPs first must refer the parents and child to a mental health practioner! Assess the child’s receptive language To make linguistic diagnoses, the SLP will have to rely on language samples recorded on audio- or videotape at home Then, remediation of the linguistic aspect of the problem can only be addressed once speech has been initiated in the therapy setting Treatment Types Two pronged approach: Individual psychotherapy to help reduce the general anxiety A behavioral program at school to slowly shape appropriate communication Treatment revolves around: contingency management: rewards speaking behavior and ignores non-speaking behavior stimulus fading: introduces a new person to a situation where the child normally speaks response initiation: encouraging child to initiate communication (Schum, 2002) Treatment Types (Krohn, Weckstein, & Wright, 1992) developed a response initiation approach Begins with a psychiatric evaluation, information presented to parents, and a brief period of therapy Children given message that speaking is necessary Therapist schedules a complete day when child will spend the day with the therapist The child is required to speak one word to the therapist before leaving the therapist’s office Most children speak within 1-2 hours, rarely more than 4 hours needed Goals are then set! (Krohn, et. Al, 1992) Psychoeducational Approach Multidisciplinary approach, includes psychologist, SLP, classroom teacher, parents Psychotherapy and Speech and Language Therapy Encourage nonverbal gestures: Making eye contact, following directions, nonverbal participation in group activities, pantomime activities, Leads to Stimulus Fading Response Initiation, whispering Expand on verbalizations by having child choose what things to say Psychoeducational Approach con’t Child must agree to whisper in SLP sessions Shaping, encourage use of other vocalizations Generalize to classroom teacher, an aide, others in the school environment, peers Cough, sounds with a kazoo, animal sounds Increase volume, child must be interested and animated about topics Generalize voice to specific words, class subjects, and finally different settings Must use reinforcing Rewards! (Giddan et. Al, 1997) Peer Approach Involve the child with peers in various activities Most selectively mute children are well accepted and liked SLP identifies which peers show a mutual interest in the child Collaborates with teacher to set up instructional situations in which the child is paired with a preferred peer Peer can also attend speech and language therapy sessions Generalize from short activities to therapy sessions to home visits to activities outside home and school (Schum, 2002) Videotape/Audiotape Approach Self Modeling Child can see what it will be like when the child talks Tape at home, listened to at therapy Good for children who are resistant to behavioral therapy Video freeforward: Videotapes of the child talking obtained in situations in which the child talks fluently are edited with videotapes of the child in situations in which the child does not talk so that the edited intervention videotape depicts that child talking in situations in which he or she has been mute. (Blum, N.J. et. Al, 1998) Treatment Issues The longer the child is silent, the more entrenched the behavior gets Course of treatment is unpredictable Based on length of time the behavior has existed, personality factors, willingness of the significant others to focus on the problem Selectively mute children often found in immigrant populations Due to cultural and linguistic differences between home and school Treatment Issues con’t Recent medical literature reports use of antidepressants to treat selective mutism Routine and structure important for an anxious child, know what is to come Helpful in treating anxiety symptoms, does not treat mute behaviors Often “slow to warm up”, let the child observe first (Schum, 2002) suggests using terms such as “shy” and “nervous” to describe feelings when they are reluctant to speak, and “brave” when they speak (Schum, 2002) Treatment Issues con’t Selectively mute children are often inadvertently rewarded for not talking Follow rules, quiet Fellow classmates often reinforce, support, and enable silence by speaking for the child Easy for people to become frustrated with the child Works Cited 1Up Health. Selective Mutism. Retrieved March, 30, 2003, from http://www.1uphealth.com/health/selective_mutism_info.html American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Atoynatan, T.H. (1086). Elective Mutism: Involvement of the mother in the treatment of the child. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 17, 15-27. Baltaxe, C.A.M. (1994, November). Communication issues in selective mutism. Paper presented at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Convention, New Orleans, LA. Blum, N.J. (1998, February). Case study: audio freeforward treatment of selective mutism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 40-43. Giddan, J.J., Ross, G.J., Sechler, L.L., Becker, B.R. (1997). Selective mutism in elementary school: multidisciplinary interventions. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 28, 127-133. Krohn, D.D., Weckstein, S.M., & Wright, H.L. (1992). A study of the effectiveness of a specific treatment for elective mutism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 711-718. Schum, R. (2002). Selective mutism: an integrated treatment approach. ASHA Leader online. Wergeland, H. (1979). Elective mutism: Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 59, 218-228.