Ability Expectation and Ableism Peace: A Prerequisite for a Culture

advertisement

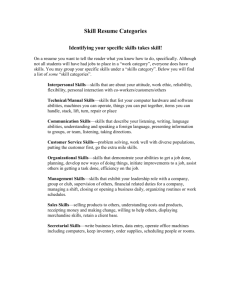

Ability Expectation and Ableism Peace: A Prerequisite for a Culture of Peace Gregor Wolbring and Jacqueline Noga University of Calgary, Faculty of Medicine, Dept of Community Health Sciences gwolbrin@ucalgary.ca for INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH ASSOCIATION(IPRA) Conference, Japan Nov 29th , 2012 Introduction Various fields have been linked to peace study from sociology to gender studies and ecology. Ability studies, the cultural investigation of ability expectations and preferences and ableism is an under used and underappreciated lens through which to analyse peace dynamics. The academic field of disability studies and disabled activists were the first to look at “cultural dynamics and the cultural impact of ability preferences, coining the term ableism as a cultural concept in the process”[1]. However, the favoritism for abilities (want stage) and ableism (need stage) is a much broader cultural reality. Ableism can be used in a positive and negative way. Every individual, household, community, group, sector, region, and country cherishes and promotes different abilities[2]; some promote the ability to consume or to compete, some the ability of free speech, some the ability to act as an individual or conversely, as a community. Some have the desire to have the ability to live in peace while others thrive on the ability to generate violence. Often these ability expectations (want stage) morph into forms of ableism where one not only desires or expects certain abilities but one perceives a given ability as essential (need stage)[3]. What abilities one favours and what ableisms one exhibits often is part of one’s self-identity which leads to an ability-based and ability-justified understanding of oneself, one’s body and one’s relationship with others of one’s species, other species[2]. It also impacts human-nature relationships[4] and the ability to have a culture of peace. Value theory of peace studies is about designing peace studies so it changes attitudes as well as imparts knowledge [5]. Value theory records what people do value and attempts to understand why they value certain things. Ableism is about valuing certain abilities and expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation (the ability desired) could be used to analyze dynamics of peace. Conflict theory emphasizes possible conflict between social groups. Conflict resolution is part of peace studies [6-8]. Various ability expectations are in direct conflict with each other. The concept of a ‘culture of peace’ was formulated at the 1989 International Congress on Peace in the Minds of Men, held in Côte d’Ivoire [9] and is central to UNESCO and the United Nations. The 1998 UN resolution (A/Res/52/13, 15 January 1998, paragraph 2)[10] calls “for the promotion of a culture of peace based on the principles established in the Charter of the United Nations and on respect for human rights, democracy and tolerance, the promotion of development, education for peace, the free flow of information and the wider participation of women as an integral approach to preventing violence and conflicts, and efforts aimed at the creation of conditions for peace and its consolidation.” A culture of peace according to article 1 of the United Nations Declaration on the culture of peace is a set of values, attitudes, traditions and modes of behaviour and ways of life based on among others: (i) Adherence to the principles of freedom, justice, democracy, tolerance, solidarity, cooperation, pluralism, cultural diversity, dialogue and understanding at all levels of society and among nations; and fostered by an enabling national and international environment conducive to peace. “[11] However, what abilities and what forms of ableism have to be tolerated? Which abilities have to be evident for a democracy to work ([12]? What forms of development? How does this play itself out among different forms of ability expectations and ableism? Culture of peace is linked to as diverse topics as water [13-17], public health[18], sport[19-24], education[25-27] and gender [28;29], What is glaring is the absence of disabled people within the culture of peace discourse and it may be that this explains why an ability studies lens is also absent. Various indicators, templates, and determinants exist to evaluate progress in achieving a culture of peace [30-43] However which ability expectations are conducive to culture of peace? Is there a hierarchy? Are some of the expectations outlined in article 1 and 2 contra indicative? Which existing ability expectations can fulfill the present and future needs and which can’t? Cultural Diversity, Disabled People and Ableism The concepts of cultural and biological diversity are often intertwined [44-48]. However, interestingly the biological diversity is non-human based, which means that disabled people and their fight for being seen as a biological diversity is not part of the biological diversity discourse. Indeed the Convention on Biological Diversity explicitly does not cover human biological diversity. The acceptance or rejection of the biological diversity of disabled people is directly linked to the acceptance or rejection of disabled people as a social group(s) with cultural identities. To give one example: if one talks about the possible birth of a child with Down Syndrome one mostly hears and reads the term “at risk of having a child with Down Syndrome”. The table below reflect the results of some key word searches in Google. It shows that the term risk has an at least 10-1000 times higher association with Down Syndrome than the term probability. The same is true for other so called ‘impairments’. Within the discourse of Down Syndrome the term risk is used to justify the availability of pre-birth tests which was first promoted for women over a certain age as they would have an ‘increased risk’ of a child with Down Syndrome. Of course, factual the term to use would be ‘probability’. Risk is a biased term with an attached negative judgement. Keyword Google Scholar Google “Genetic risk” “Down Syndrome” 1,490 46,300 “Genetic probability” “Down Syndrome” 2 28 “Genetic likelihood” “Down Syndrome” 2 11 risk “Down Syndrome” 22,600 1,790,000 Probability “Down Syndrome” 5210 162,000 Likelihood “Down Syndrome” 5440 183,000 Neutral language such as the following is rejected by most: “Down syndrome is a naturally occurring chromosomal arrangement that has always been a part of the human condition. The occurrence of Down syndrome is universal across racial and gender lines, and it is present in approximately one in 800 births in Canada. Down syndrome is not a disease, disorder, defect or medical condition. It is inappropriate and offensive to refer to people with Down syndrome as "afflicted with" or "suffering from" it. Down syndrome itself does not require either treatment or prevention. (Position Statement on Redefining Down Syndrome Approved November 2003 Canadian Down Syndrome Society)”[49] The negative form of ableism and the linked disablism experienced by disabled people is a serious problem for a culture of peace. Human security is seen as essential for a culture of peace [32;50]. The human security discourse covers economic security, food security, health security, environmental security, personal security, community security, and political security. However they miss two essential securities namely ability security and self-identity security [51]. “Ability security means that one is able to live a decent life with whatever set of abilities one has, and that one will not be forced to have a prescribed set of abilities to live a secure life (e.g. even if one doesn’t have the ability to walk, he or she should be able to secure employment)” [51;52]. “Self-identity security could be seen as a subset of personal security and means that one is accepted with one’s set of abilities and that one should not be forced (physically or by circumstance) to accept a perception of oneself one does not agree with (e.g. one is not expected to have the ability to walk or is seen as a ‘deficient product’ if one cannot walk)” [51;52]. Ability and self-identity security are not getting much currency as ability expectations is so far an underused lens and what is debated within disability studies field is often not used in other discourses[53]. However without dealing with negative forms of ableism we see new barriers to various forms of peace. We see a decrease in intergenerational peace partly linked to a rise in ageism and youthism, two negative ‘isms’ supported by ability expectations. Ability expectations which are intrinsic to an anthropocentric view of dealing with nature [4] might make a peace between humans in existence today and humans to come problematic. Selfidentity security is of importance to women and ethnic and cultural oppressed groups who are punished simply for who they are[51]. However we do not apply this mind frame to ability related self-identity. Culture of Peace and Science and Technology Advancements In April 2007 the UNESCO executive was given a report titled "A Strategic Framework for the Future of the Sciences in UNESCO” (1) which talks about reorienting UNESCO science programs to contribute more to: poverty reduction; peace; better living standards (especially for traditionally excluded segments of the population); empowerment of people; dialogue and integration of mainstream science with traditional, local and indigenous sciences of diverse cultures; diversity; sustainability; and distributive justice. How will the language in the culture of peace documents and the report be interpreted with the interventions made possible by new and emerging technologies? How will the language be used with respect to: the enhancement of animals (2) (which will redefine the relationship between humans and animals); immortality and longevity research (which could lead to intergenerational strife); molecular manufacturing (which will lead to a total collapse of the trade system as we know it today); and new products that can modify the appearance and functioning of the human body beyond existing norms and species-typical boundaries which will lead to self-identity and ability security problems? So far, policies around new and emerging technologies have failed to establish a culture of peace Ability Peace: An elusive concept so far Peace in relation to ability expectations does not exist between so called disabled and nondisabled people. One can think of this notion of peace in relation to abilities as ‘ability peace’. Ability peace is also elusive in other aspects. One could say that judging ones culture based on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) numbers assumes certain abilities in the given culture and certain ways of organizing the culture. This pits groups with different ability expectations based social organizations against the GDP base ones. The ability conflict based on divergent ability expectations between so called disabled and nondisabled people will become more prevalent and severe with the anticipated ability of new and emerging sciences and technologies: to generate human bodily enhancements in many shapes and forms[54] with an accompanying ability divide and the appearance of the external and internal techno poor disabled; [55] to generate, modify and enhance non-human life forms; to separate cognitive functioning from the human body; and to modify humans to deal with the aftermath of anti-environmentalism[56]. We can already observe a changing perception of ourselves, our body, and our relationships with others of our species, other species and our environment. New forms of ableism are appearing where body related ability expectation and ableism focus on beyond the species-typical [57-70] (transhumanization of ability expectations and ableism). It was predicted in 2008 that we will see a “climate change-driven appeal for a transhuman version of ableism, where the transhumanisation of humans is seen as a solution for coping with climate change”[71]. Indeed we see the first academic papers of authors with transhumanist backgrounds putting forward this angle [72]. Conclusion: As we are able to further enhance the abilities of the body through science and technology, ability and self-identity security will increasingly be of importance to every person, individual, household, community, group, sector, region, and country who does not want to modify their body according to the wishes of others or who cannot afford these modifications. People who currently see themselves as the norm, as non-impaired or ‘species-typical,’ will be seen by others as impaired or deficient if they do not enhance themselves according to ‘new norms,’ or the wishes of powerful others. We have seen for decades, if not centuries, that when science and technology develops new tools that are external to the body, people often have to learn how to use these devices so that they can capitalize on the new abilities if they want to keep their job or get a new job. Although these non-impaired species-typical labeled people might not see it as such, they also have no ability security. They are forced to adopt the latest advances or they will be unemployable. For instance as the typewriter diffused across the United States, secretaries with perfect penmanship (a long valued ability) were replaced by secretaries who could type at high speeds. If predictions of new and emerging nanoscale S&T products and processes come true and if we focus a lot on the ability of competitiveness and consumerism we will see this dynamic not only speed up we might see a move towards the transhumanization of ableism. Those people now considered nonimpaired, species-typical, will no longer have a competitive set of abilities to be considered fit workers. They will have to decide whether they want a job badly enough to modify their body so they meet the new expected types of abilities. Without dealing with the culture of ableism one cannot deal with the transhumanized version of ableism. How disabled people are treated in public policy discourse pertaining to science and technology will have an impact on a group of people we can expect to grow – the techno poor disabled people; people who do not have, who cannot afford, or who do not want certain cellular, genomic or bodily enhancements[55]. This new ‘social group’ will be as badly treated and will be seen as deficient as the ‘traditional disabled people’ of today. Eliminating the negative forms of ableism is essential if we want to diminish, reverse, or prevent the conflict that may result from the disruptive potential of many abilities to come. The field of Ability Studies was proposed[56]. It was described as follows: “Ability Studies investigates: (a) the social, cultural, legal, political, ethical and other considerations by which any given ability may be judged, and which leads to favouring one ability over another; (b) the impact and consequence of favouring certain abilities and rejecting others; (c) the consequences of ableism in its different forms, and its relationship with and impact on other isms; (d) the impact of new and emerging technologies on ableism and consequent favouritism towards certain abilities and rejection of others; and (e) identification of the abilities that would lead to the most beneficial scenario for the maximum number of people in the world” [56]. Ability Studies might be essential to investigate ability peace which is essential to peace studies. Reference List 1. Wolbring, G. Expanding Ableism: Taking down the Ghettoization of Impact of Disability Studies Scholars. Societies 2012, 2 (3), 75-83. 2. Wolbring, G. Why NBIC? Why human performance enhancement? Innovation; The European Journal of Social Science Research 2008, 21 (1), 25-40. 3. Wolbring, G. Eco-ableism. Anthropology News 2012, Sept. 14. 4. Wolbring, G. Ableism and energy security and insecurity. Studies in Ethics, Law, and Technology 2011, 5 (1), Article 3. 5. Eckhardt, W. Peace studies and attitude change: A value theory of peace studies. Peace & Change 1984, 10 (2), 79-85. 6. Jacoby, T. Understanding Conflict & Violence; Routledge: 2012. 7. Kehoe, A. B. Legitimating Peace Studies. Expanding American Anthropology, 1945-1980: A Generation Reflects 2012, 193. 8. Danesh, H. B. Human Needs Theory, Conflict, and Peace. The Encyclopedia of Peace Psychology 2012. 9. UNESCO UNESCO -Mainstreaming the culture of peace. UNESCO 2012.Available online: http://www3.unesco.org/iycp/uk/uk_sum_cp.htm (accessed on 23rd September 2012). 10. UNESCO Resolution adopted by the General Assembly [without reference to a Main Committee (A/52/L.4/Rev.1 and Add.1)] 52/13. Culture of peaceCulture of Peace. UNESCO 1998.Available online: http://www3.unesco.org/iycp/kits/res52-13_en.htm (accessed on 23rd September 2012). 11. United Nations Resolution adopted by the General Assembly [without reference to a Main Committee (A/53/L.79] 53/243. Declaration and Programme of Action on a Culture of Peace. United Nations 1999.Available online: http://cpnn-world.org/resolutions/resA-53243B.html (accessed on 23rd September 2012). 12. Wolbring, G. Nanotechnology for Democracy versus Democratization of Nanotechnology. In Little by Little: Expansions of Nanoscience and Emerging Technologies, Harro van Lente, Christopher Coenen, Torsten Fleischer, Kornelia Konrad, Lotte Krabbenborg, Colin Milburn, François Thoreau, Eds.; AKA-Verlag/IOS Press: Dordrecht, 2012. 13. Broner, I. Water and peace in the Middle East : J. Isaac and H. Shuval (Editors), Proceedings of the First Israeli-Palestinian International Academic Conference on Water, 10-13 December 1992, Zurich, Switzerland, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, New York, 552 pp., US$ 222.75/Dfl. 390.00, ISBN 0-444-81464-7. Agricultural Water Management 1996, 29 (3), 339-340. 14. Ruff, J. F. Rivers of Eden : Rivers of Eden: The Struggle for Water and the Quest for Peace in the Middle East, by Daniel Hillel, Oxford University Press, 1994, 355 pp. $30.00 (cloth), ISBN 019-58068-8. Agricultural Water Management 1997, 32 (2), 211-212. 15. Heinzen, B. 4.7 Water for peace in the Middle East: Rapporteur: Barbara Heinzen. Participants: 200. Water Policy 2001, 3 (Supplement 1), S153-S154. 16. Turton, A. 4.8 Water for peace in Southern Africa: Rapporteur: Anthony Turton. Participants: 150. Water Policy 2001, 3 (Supplement 1), S155-S157. 17. Eckstein, Y.; Eckstein, G. E. Groundwater Resources and International Law in the Middle East Peace Process. Water International 2003, 28 (2), 154-161. 18. Laaser, U.; Donev, D.; Bjegovic, V.; Sarolli, Y. Public health and peace. Croatian Medical Journal 2002, 43 (2), 107-113. 19. United Nations Sport for Development and Peace: the way forward Report of the SecretaryGeneral. United Nation Webpage 2006. 20. Commissioned by Sport for Development and Peace International Working Group (SDP IWG) Secretariat Literature reviews on sport for development and peace. righttoplay. org 2007.Available online: http://www.righttoplay.com/norway/news-andmedia/Documents/Policy%20Reports%20docs/Literature%20Reviews%20SDP.pdf#page=1 24 (accessed on 23rd September 2012). 21. Kidd, B. A new social movement: Sport for development and peace. Sport in Society 2008, 11 (4), 370-380. 22. Right to Play Harnessing the power of sport for development and peace: Recommendations for governments; Chapter 5 Sport and persons with disabilities: Fostering inclusion and wellbeing; Sport for development and peace, International working group: 08. Available online: http://www.righttoplay.com/International/news-andmedia/Documents/Policy%20Reports%20docs/Harnessing%20the%20Power%20%20FULL/Chapter5_SportandDisability.pdf (accessed on 23rd September 2012). 23. United Nations Sport as a means to promote education, health, development and peace. Sixty-fifth sessionAgenda item 11 United Nations 2010.Available online: http://www.un.org/wcm/webdav/site/sport/shared/sport/pdfs/A%2065%20L.4%20%20% 20%20N1058367.pdf (accessed on 23rd September 2012). 24. Tiessen, R. Global Subjects or Objects of Globalisation? The promotion of global citizenship in organisations offering sport for development and/or peace programmes. Third World Quarterly 2011, 32 (3), 571-587. 25. Duffy, T. Peace education in a divided society: creating a culture of peace in Northern Ireland. Prospects 2000, 30 (1), 15-29. 26. Danesh, H. B. Towards an integrative theory of peace education. Journal of Peace Education 2006, 3 (1), 55-78. 27. Carter, C. C. Conflict Resolution and Peace Education: Transformations across Disciplines; ERIC: 2012. 28. Breines, I. A gender perspective on a culture of peace. Work 1999, 12, 13. 29. Reardon, B. A. Education for a culture of peace in a gender perspective; ERIC: 2001. 30. De Rivera, J. Assessing the basis for a culture of peace in contemporary societies. Journal of Peace Research 2004, 41 (5), 531-548. 31. De Rivera, J. A template for assessing cultures of peace. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology; Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 2004, 10 (2), 125. 32. De Rivera, J.; Kurrien, R.; Olsen, N. The emotional climate of nations and their culture of peace. Journal of Social Issues 2007, 63 (2), 255-271. 33. De Rivera, J.; P+íez, D. Emotional climate, human security, and cultures of peace. Journal of Social Issues 2007, 63 (2), 233-253. 34. De Rivera, J. Emotional Climate for Peace. 2012. 35. Morales, J.; Leal, J. A. Indicators for a culture of peace in Spain. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology; Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 2004, 10 (2), 147. 36. Ginty, R. M. Indicators+: A proposal for everyday peace indicators. Evaluation and Program Planning 2012. 37. Bush, K. A measure of peace: Peace and conflict impact assessment (PCIA) of development projects in conflict zones. The Peacebuilding and Reconstruction Program Initiative. Dostupn+® z:< http://www. idrc. org/uploads/user-S/10533919790A_ Measure_of_Peace. pdf 1998. 38. Wenden, A. Educating for a culture of social and ecological peace; SUNY Press: 2004. 39. Milani, F. M.; Branco, A. U. Assessing Brazil's culture of peace. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology; Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 2004, 10 (2), 161. 40. Justice, P. a. C. T. W. C. o. C. Alternative Globalization Addressing Peoples and Earth (AGAPE). World Council of Churches 2005.Available online: http://www.oikoumene.org/resources/documents/assembly/porto-alegre-2006/3preparatory-and-background-documents/alternative-globalization-addressing-peopleand-earth-agape.html (accessed on 23rd September 2012). 41. Coleman, P. T. Conclusion: The Essence of Peace? Toward a Comprehensive and Parsimonious Model of Sustainable Peace. Psychological Components of Sustainable Peace 2012, 353369. 42. Tasiran, A. C.; Quao-Yuan, L. Factors to theorise the Global Peace Index. 2012. 43. Kodila-Tedika, O. Determinants of Peace: A Cross-Country Analysis. 2012. 44. Breckenridge, L. P. Protection of Biological Cultural Diversity: Emerging Recognition of Local Community Rights in Ecosystems under International Environmental Law. Tenn. L. Rev. 1991, 59, 735. 45. Redclift, M. Sustainable Development - Needs, Values, Rights. Environmental Values 1993, 2 (1), 320. 46. UNESCO . UNESCO UNIVERSAL DECLARATION ON CULTURAL DIVERSITY. 2001. 47. Rapport, D.; Maffi, L. The Dual Erosion of Biological and Cultural Diversity: Implications for the Health of Ecocultural Systems. Nature and Culture: Rebuilding Lost Connections 2012, 103. 48. Harmon, D.; Woodley, E.; Loh, J. Measuring Status and Trends in Biological and Cultural Diversity. Nature and Culture: Rebuilding Lost Connections 2012, 41. 49. Canadian Down Syndrome Society Down Syndrome Redefined. Canadian Down Syndrome Society webpage 2007.Available online: http://www.cdss.ca/site/about_us/policies_and_statements/down_syndrome.php (accessed on 23rd September 2012). 50. Cockell, J. G. Conceptualising peacebuilding: human security and sustainable peace. Regeneration of War-Torn Societies 2000, 21. 51. Wolbring, G. Ableism and Favoritism for Abilities Governance, Ethics and Studies: New Tools for Nanoscale and Nanoscale enabled Science and Technology Governance. In The Yearbook of Nanotechnology in Society, vol. II: The Challenges of Equity and Equality, Susan Cozzens, Jameson M.Wetmore, Eds.; Springer: New York, 2010. 52. Wolbring, G. Human Security and NBICS. Innovationwatch. com webpage 2006.Available online: http://www.innovationwatch.com/choiceisyours/choiceisyours.2006.12.30.htm (accessed on 23rd September 2012). 53. Wolbring, G. Expanding Ableism: Taking down the Ghettoization of Impact of Disability Studies Scholar. Societies 2012, 2 (3), 75-83. 54. Coenen, C.; Schuijff, M.; Smits, M.; Klaassen, P.; Hennen, L.; Rader, M.; Wolbring, G. Human Enhancement Study;(IP/A/STOA/FWC/2005-28/SC35, 41 & 45) PE 417.483; European Parliament: 09. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/stoa/publications/studies/stoa2007-13_en.pdf (accessed on 23rd September 2012). 55. Wolbring, G. The unenhanced underclass. In Better Humans? The politics of human enhancement, Wilsdon, J. M. P., Ed.; Demos Institute: 2006. 56. Wolbring, G. Why NBIC? Why Human Performance Enhancement? Innovation; The European Journal of Social Science Research 2008, 21 (1), 25-40. 57. Wolbring, G. Nanotechnology and the Transhumanization of Health, Medicine, and Rehabilitation. Lee Kleinmann, D., Delborne, J., Cloud-Hansen, K., Handelsman, J., Eds.; Mary Ann Liebert: New Rochelle, NY, 2010; pp 290-303. 58. Wolbring, G. Obsolescence and body technologies Obsolescencia y tecnologías del cuerpo. Dilemata International Journal of Applied Ethics 2010, 2 (4), 67-83. 59. Alfred Nordmann Nano-Bio-Info-Cogno-Socio-Anthro-Philo- HLEG Foresighting the New Technology Wave Converging Technologies " Shaping the Future of European Societies; 04. Available online: http://europa.eu.int/comm/research/conferences/2004/ntw/index_en.html (accessed on 23rd September 2012). 60. Baylis, F.; Robert, J. S. The inevitability of genetic enhancement technologies. Bioethics 2004, 18 (1), 1-26. 61. C.CHRISTOPHER HOOK . TRANSHUMANISM AND POSTHUMANISM . 2003. 62. International Centre for Bioethics, C. a. D. section on transhumanism. 2005. 63. International Centre for Bioethics, C. a. D. section on cybernetics. 2005. 64. Krishna Guha Lunch with the FT: Meaty arguments Peter Singer interviewed by Krishna Guha . Financial Times, 2005. 65. M.Roco, W. B. e. Converging Technologies for Improving Human Performance: Nanotechnology, Biotechnology, Information Technology and Cognitive Science. 2003. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht Hardbound. 66. McMillan Reference . ENCYCLOPEDIA OF BIOETHICS 3rd Edition . 2003. 67. Rick Weiss Cosmetic Gene Therapy's Thorny Traits . Washington Post, 1997, p A01. 68. Transtopia . Transhumanism. 2005. 69. Word Transhumanist Association. What is Transhumanism? 2005. 70. World Transhumanist Association . Transhumanist declaration . 2002. 71. Wolbring, G. "Is there an end to out-able? Is there an end to the rat race for abilities?". Journal: Media and Culture 2008, 11 (3). 72. Liao, S. M.; Sandberg, A.; Roache, R. Human engineering and climate change. Ethics, Policy & Environment 2012, 15 (2), 206-221.