Trafficked and Silenced:

How Mainstream Trafficking Discourse Stifles the

Voices and Shapes the Stories of Victims

Dr Ramona Vijeyarasa

Sydney

11 February 2015

Paper in context

• Based on research conducted in Ukraine, Vietnam

and Ghana as well as secondary literature

• More detailed findings published in “Sex, Slavery

and the Trafficked Woman: Myths and

Misconceptions about trafficking and its victims”

(Ashgate, 2015)

2

Outline

1. Methodology

2. What are the three main trafficking

archetypes?

3. How has the “suffering victim” been

analysed in other contexts?

4. How does this apply in the context of

trafficking and how can we dispel these

archetypes?

3

Methodology

• Conducted fieldwork: Ukraine; Vietnam and Ghana

• Involved questionnaires completed by returned victims

housed in shelters or accessing NGO or government

reintegration support

• Interviews with experts from UN agencies, government

authorities, international organisations, donors,

development banks, NGOs

4

Methodology

104 completed questionnaires and 50 key informant interviews

5

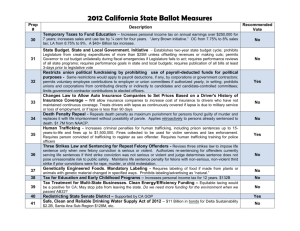

A note on the evolution of trafficking discourse

Dominant

focus on

sexual

exploitation.

Stereotypes

are

pervasive

Appearance

of

alternative

approaches

Lack of

empirical

evidence to

defend

alternative

approaches

Ongoing

focus on

sexual

exploitation

and

persistence

of

stereotypes

6

Three Mainstream trafficking

archetypes

1. The naïve woman

2. The inviolable man

3. The innocent women i.e. perpetrating male

7

Mainstream trafficking archetypes:

The naïve woman

A Nepalese girl, Chamoli ran away from home with her

boyfriend to India at the age of 16. It was only when she

arrived in the city of Poona that Chamoli discovered her

boyfriend’s intention to sell her to a brothel (Balos, 2004:

137; Coomaraswamy, 2000: ¶12).

8

Mainstream trafficking archetypes:

The inviolable man

•

•

•

•

Women are “more vulnerable than men to being trafficked”

(Mediterranean Institute of Gender Studies, 2007: 6).

Trafficking “has its roots in gender politics and sexual inequalities,

linked to widespread economic poverty” (Poudel and Carryer, 2000:

74).

There is a “gender imbalance in human trafficking”. Women “often

have no individual protection or recognition under the law, inadequate

access to healthcare and education, poor employment prospects, little

opportunity to own property” as well as “high levels of social isolation.

All this makes some women easy targets for harassment, violence, and

human trafficking” (US Department of State, 2009: 36), all at the hands

of men.

Dearth of literature on the trafficking of men (see Surtees, 2009 on

trafficking of men from Ukraine and Belarus and Horwood, 2009 on

irregular migration of men from East Africa and the Horn to South

Africa).

9

Mainstream trafficking archetypes:

The good woman

• Both trafficking and prostitution as “highly gendered

systems that result from structural inequality between

women and men on a world scale”. She continues by noting

how “[m]en create the demand and women are the supply”

(Hughes, 2006: 10).

• Significantly less recognition is given in the academic

literature to the female perpetrator.

• While it is a norm to hear references to the “madam” in

literature on sex work (e.g. Bernstein, 2007; Ward and Day,

2006; Dandona et al., 2006; Wahab, 2002; Thu Hong, 1998),

the female trafficker is not often discussed.

10

Mainstream trafficking archetypes:

The good woman

The human trafficker is a young carpenter who moves from the Red River

Delta to Lào Cai province to work for small wood processing factory. He has

the gift of the gab, so he is very persuasive...During the time he is working

in the factory, he meets and falls in love with a girl from Giầy ethnic

minority. He tells her family that he will take her to his home village to

introduce her to his family. In fact he has taken the girl to China and sold her

to a prostitute house (District level government official, Department of

Social Evils Prevention, Lào Cai, 1 October 2009).

11

The suffering victim in other contexts:

Agustín and Brown

•

•

•

Laura Agustín: “[i]t has long been recognised that people

who are considered “victims” or “deviants” are likely to tell

members of mainstream society what they believe they

want to hear” (2004: 6).

Agustín: “many make their present circumstances appear

to be the fatal or desperate result of a past event” (2004:

6).

Agustín refers to the comments of one Dominican research

participant, who said, “[a]fter all, if we were forced to be

what we are now, we cannot be blamed for it” (2004: 6).

12

The suffering victim in other contexts:

Agustín and Brown

•

•

•

•

Wendy Brown: “totalizing descriptions of women’s experiences that

are the inadvertent effects of various kinds of survivor stories” (2005:

92).

The porn star who feels exploited “invariably monopolizes the feminist

truth about sex work”, while sexual abuse and violation occupy what

Brown refers to as the “feminist knowledge terrain of women and

sexuality” (Brown, 2005: 92).

“…confession is the site of production of truth” and what results is a

tendency “to reinstate a unified discourse in which the story of

greatest suffering becomes the true story of woman” (Brown, 2005:

92).

Suffering is a requirement

13

Dispelling trafficking’s archetypes:

The rationale and voluntary victim

•

…many of them are aware, to a certain extent, of the risks when they

set out on their adventure (A. Bruce, former Chief of Mission, IOM

Vietnam; Head of Regional Office for Asia, IOM Bangkok, 21 September

2009).

•

From the point of [a] trafficker, why would I kidnap somebody if I can

just offer a job to someone and they gladly agree and go with me? (O.

L. Kustova, Legal Adviser, Law Enforcement Section, US Embassy to

Ukraine, 2 September 2009)

14

Dispelling trafficking’s archetypes:

The rationale and voluntary victim

•

•

•

In data collected from Ukraine, in 67.3% of cases, the

respondent’s mother was aware of the decision to leave

Ukraine; fathers were aware in one-third of cases.

In only 4.8% of cases, no individual related or known to the

victim was aware of the respondent’s decision to leave

Ukraine.

Such responses contradict the suggestion that these

victims were kidnapped, abducted or otherwise

unexpectedly coerced to leave Ukraine and, moreover,

show that there was a level of pre-planning for this

potential movement.

15

Dispelling trafficking’s archetypes:

The rationale and voluntary victim

• Rosanne Rushing (2006): “The family’s perception of daughters as a

source of reliable remittances and community norms supporting youth

migration contribute to promote the migration of daughters to the

cities” (Rushing, 2006: 481).

• Rushing: parents “expect their daughters to remain in the city

indefinitely as a secure source of income”, many women stay despite

exploitative conditions and a desire to return home (2006: 489-490).

• Busza’s study – of Vietnamese women undertaking commercial sex work

in Cambodia – stated that they were “ashamed” of sex work and that it

was “bad work”, yet reported pride (Busza, 2004: 240-241).

16

Dispelling trafficking’s archetypes:

The male victim

• Based on data from Belarus and Ukraine in which

male victims accounted for 28.3 per cent and 17.6

per cent of the IOM assisted caseload respectively

between 2004 and 2006, i.e. around 685 trafficked

men (Surtees, 2008: 9).

• Only 14 male respondents in my survey data.

17

Dispelling trafficking’s archetypes:

Where are the male victims?

Non genderneutral

response

No shelters

for men

Focus on

child

trafficking

Government

and civil

society

intervention

Focus on

sexual

exploitation

18

Dispelling trafficking’s archetypes:

The female perpetrator

• Empirical evidence for the male trafficker?

o Erin Denton: Of 191 incidents of human trafficking that were

reported in international electronic media over a 6 month period,

the gender of traffickers was not mentioned in 32 per cent of cases

(2010: 18).

• The role of female traffickers?

• Sometimes they are used as success stories. This woman says, ‘I was

there. I earned a lot of money. I purchased an apartment for my

parents or myself. It is easy. Do not worry’. (Olena Kustova from the

US Embassy in Ukraine, 2 September 2009)

• I would say that according to Ukrainian legislation, for instance, a

woman who has children can request the court to reduce her

sentence or release her because no one can care for her small

children. Sometimes traffickers take these into account and pick up

recruiters who can later be released because of these circumstances

(Olena Kustova from the US Embassy in Ukraine, 2 September 2009)

• Wei Tang: Female Melbourne brothel owner convicted of slavery

19

offences under Australia’s Criminal Code

Concluding remarks

• Need for methodologically sound evidence to dispel

archetypes

• Provide an environment conducive to “story telling”

“that is neither confessional nor normative in a

moralizing sense”

• Ensure victimhood is not denied where narrative does

not conform

20