ten elements of symbolic interactionism

advertisement

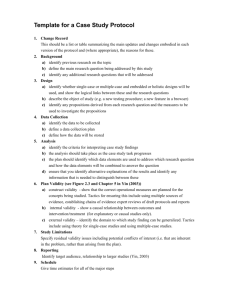

CASE STUDY © LOUIS COHEN, LAWRENCE MANION & KEITH MORRISON STRUCTURE OF THE CHAPTER • • • • • • • • • • What is a case study? Generalization in case study Reliability and validity in case studies What makes a good case study researcher? Examples of kinds of case study Why participant observation? Planning a case study Data in case studies Recording observations Writing up a case study WHAT IS A CASE STUDY? • • • • • A case study is a specific, holistic, often unique instance that is frequently designed to illustrate a more general principle; The study of an instance in action; The study of an evolving situation; Case studies portray ‘what it is like’ to be in a particular situation; Case studies often include direct observations (participant and non-participant) and interviews. WHAT IS A CASE? • • • • A person; A group; An organization; An event; ELEMENTS OF CASE STUDY • Rich, vivid and holistic description (‘thick description’) and portrayal of events, contexts and situations through the eyes of participants (including the researcher); • Contexts are temporal, physical, organizational, institutional, interpersonal; • Chronological narrative; • Combination of description, analysis and interpretation; • Focus on actors and participants; • Let the data speak for themselves (don’t overinterpret). TYPES OF CASE STUDY • Exploratory (pilot); • Descriptive (e.g. narrative); • Explanatory. Stake: • Intrinsic case studies: (to understand the case in question); • Instrumental case studies (examining a particular case to gain insight into an issue or theory); • Collective case studies (groups of individual studies to gain a fuller picture). DESIGNS IN CASE STUDY • Single-case design – a critical case, an extreme case, a unique case, a representative or typical case, a revelatory case (an opportunity to research a case heretofore unresearched. • Embedded, single-case design – more than one ‘unit of analysis’ is incorporated into the design, e.g. a case study of a whole school might also use sub-units of classes, teachers, students, parents, and each of these might require different data collection instruments. • Multiple-case design – comparative case studies within an overall piece of research, or replication case studies. • Embedded multiple-case design – different sub-units may be involved in each of the different cases, and a range of instruments used for each sub-unit, and each is kept separate to each case. KEY QUESTIONS IN CASE STUDY • What exactly is the case(s)? • How are cases identified and selected? • What kind of case study is this (what is its purpose)? • What is reliable evidence? • What is objective evidence? • What is an appropriate selection to include from the wealth of generated data? • What is a fair and accurate account? • Under what circumstances is it fair to take an exceptional case or a critical event? • What kind of sampling is most appropriate? KEY QUESTIONS IN CASE STUDY • To what extent is triangulation required and how will this be addressed? • What is the nature of the validation process in the case study? • How will the balance be struck between uniqueness and generalization? • What is the most appropriate form of writing up and reporting the case study? • What ethical issues are exposed in undertaking the case study? DATA IN CASE STUDIES • • • • • Observations (structured to unstructured); Field notes; Interviews (structured to unstructured); Documents; Numbers. TRIANGULATION • • • • • • • Time; Place; Methodologies; Instrumentation; Researchers; Participants; Theory (interpretive paradigms/lenses). ROLE OF RESEARCHER (Stake, 1995) TEACHER ADVOCATE EVALUATOR BIOGRAPHER INTERPRETER STRENGTHS OF CASE STUDIES • • • • Can establish cause and effect; Rooted in real contexts; Regard context as determinant of behaviour; The whole is more than the sum of the parts (holism); • Strong on reality; • Recognize and accept complexity,uniqueness and unpredictability; STRENGTHS OF CASE STUDIES • Lead to action (link to action research); • Can focus on critical incidents; • Written in accessible style and are immediately intelligible; • Practicable (can be done by a single researcher); • Can permit generalizations and application to similar situations; GENERALIZATION IN CASE STUDY • From the single instance to the class of instances; • From features of the single case to classes with the same features; • From the single features of part of the case to the whole of the case; • From a single case to a theoretical extension or theoretical generalization. RELIABILITY AND VALIDITY IN CASE STUDIES • • • • • • • • Construct validity Internal validity External validity Concurrent validity Convergent validity Ecological validity Reliability Avoidance of bias THE NEED FOR A CHAIN OF EVIDENCE A GOOD CASE STUDY RESEARCHER MUST BE . . . • • • • • • • • An effective questioner, listener and prober An effective observer Able to make informed inferences Adaptable to changing and emerging situations Versed in research methods Able to collate and synthesize data Able to maintain confidences and to act with discretion and confidentiality Versed in relevant subject knowledge WHY PARTICIPANT OBSERVATION? • Observation studies are superior to experiments and surveys when data are being collected on non-verbal behaviour. • Investigators can discern ongoing behaviour as it occurs and are able to make appropriate notes about its salient features. • Researchers can develop more intimate and informal relationships with those they are observing, and in natural environments. • Case study observations are less reactive than other types of data-gathering methods. • Direct observation is faithful to the real-life, in situ and holistic nature of a case study. PLANNING A CASE STUDY CONSIDER: • The particular circumstances of the case: – The possible disruption to individual participants that participation might entail; – Negotiating access to people; – Negotiating ownership of the data; – Negotiating release of the data. PLANNING A CASE STUDY CONSIDER: • The conduct of the study including: – The use of primary and secondary sources; – The opportunities to check data; – Triangulation; – Peer and respondent validation; – Reflexivity; – Data collection methods; – Data analysis and interpretation; – Theory generation; – Writing the report • Consequences of the research (and for whom). STAGES IN CASE STUDY • Start with a wide field of focus; • Progressive focusing; • Draft interpretation/report (avoid generalizing too early). CONTINUA OF DATA IN CASE STUDIES QUALITATIVE QUANTITATIVE NATURAL ARTIFICIAL UNSTRUCTURED STRUCTURED NARRATIVE NUMERIC JOURNALISTIC STATISTICAL DATA TYPES IN CASE STUDY • • • • • • • Documents Archival records Interviews Direct observation Participant observation Physical artifacts Actual data gathered, recorded and organized by entry, and the researcher’s ongoing analysis/report/comments/narrative on the data. RECORDING OBSERVATIONS • Record the notes as quickly as possible after observation. • Discipline yourself to write notes quickly. • Dictating rather than writing is acceptable. • Word-processing field notes is vastly preferable to handwriting. • Keep backup copies of field notes. • The notes ought to be full enough adequately to summon up for one again, months later, a reasonably vivid picture of any described event. WRITING UP A CASE STUDY • Executive summary followed by detail. • A prose account is provided, interspersed with relevant figures, tables, emergent issues, analysis and conclusion. • Examine the same case through two or more lenses (e.g. explanatory, descriptive, theoretical). • Follow a simple sequence or chronology, interspersed with commentaries, interpretations and explanations. • Have a structure that follows theoretical constructs or a case that is being made. • Order by main issues. • Consider rival explanations. PROBLEMS WITH CASE STUDIES • • • • Difficult to organize; Limited generalizability; Problems of cross-checking; Risk of bias, selectivity and subjectivity; AN EXAMPLE OF A CASE STUDY: LEARNING TO LABOUR Willis, P. (1977) Purpose: to find out how working class kids get working class jobs and others let them Considerations: • the need to link macro and micro sociology; • The need to analyze schooling in terms of macro-constraints and human agency • The need to see schools as sites of contestation, resistance and struggle in both a micro and macro sense. PROCEDURE (a) Ethnographic study of a group of males ini their final year of school and then in their first year beyond school, working in factories and other short-term, manual employment (b) Study of their behaviour in school and how it feeds into their choice of post-school occupations ELEMENTS OF LADS’ CULTURE • Opposition to authority and rejection of conformity: clothing; smoking and lying; drinking; • Celebration of the informal group; • Excitement is out of school; • Rejection of the literary tradition; • Sexism; • Racism. SHOP-FLOOR CULTURE • Masculine chauvinism – sexism; • Attempt to gain informal control of the work process; • Rejection of the conformists in the factory; • Rejection of ‘theory’ and certification; • Rejection of the coercion which underlines the teaching paradigm; • Shirking work/absenteeism/taking time off; • No break on the taboo of informing; • Speaking up for yourself; • Present oriented; • Rejection of mental labour and celebration of manual labour. MAIN FINDINGS • The behaviours and values which the lads sought and practised in school lead them into choosing deliberately and positively those post-school occupations that reinforce and let them practise these behaviours and values; • There is a continuity between the lads’ life styles at school and their life styles out of school and postschool; • The need for immediate cash, immediate gratification, anti-authority behaviour, chauvinism, rejection of mental labour, and celebration of the informal group find expression in school and postschool. CONCLUSION Working class kids get working class jobs because that is what they choose and what they are driven to choose by the values that they hold.