Gastroesophageal Reflux Childhood

advertisement

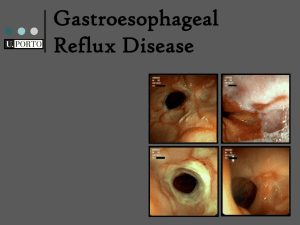

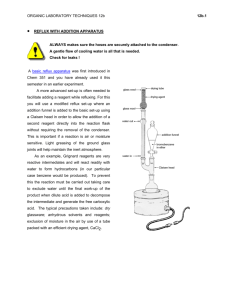

Gastroesophageal Reflux Childhood Mary Ann Hudson, RN OSU College of Nursing Patient History • 10 year old male with chief complaint of stomach and throat pain that worsens at night and with large, rich meals. • Patient has history of infant reflux and was given liquid Zantac until one year of age when symptoms of arching and crying with meals resolved without medication. • Father has history of gastroesophageal reflux and peptic ulcer. Father has recently completed a two-week Prilosec treatment for breakthrough reflux after being treated for h. pylori. • Patient lives with father on the weekends along with his twin sister. During the week, patient lives with twin sister and his mother. Parents have been divorced for a little over a year. Custody agreement requires that both parents be present at medical/health appointments unless it is an emergency. Both mother, father, and twin sister are in exam during this visit. • Mother has no significant history of reflux or gastrointestinal disease. Sister is symptom free. Mother reports patients symptoms appear following every meal, father disagrees with this history, patient is not sure. Patient History • Patient questioned about supraesophageal symptoms of GER. • Patient and parents deny apnea. • Patient and parents deny asthma or wheezing. • Patient has a significant history of sinusitis and Otitis Media. • Patient and parents deny hoarseness, but endorse post meal “sounds” like wet burping, excessive swallowing, and throat clearing. • Patient and parents endorse dry, constant cough. • Patient and parents endorse frequent sore throat complaints. Patient has a significant history of sore throat visits negative for GABS pharyngitis or other symptoms. Significant Visit Observations related to Barnard Model of Health Patient Exam • Patient HEENT, cardiac, pulmonary, M/S, Neurological, exams are all WNL. Patient is calm, cooperative, and has a normal body temperature. • Patient BS are hyperactive in both upper quadrants. Patient tolerates deep abdominal palpation in all quadrants except peri-umbilically. • Today, though patient complains of throat pain, no erythema, exudate, or injury is noted in the oropharynx. • At this time, no labs or studies will be ordered, though if first-line treatment is unsuccessful, an h. pylori lab is a reasonable next step given father’s previous Dx. Diagnosis and Treatment Plan Dx: Gastroesophageal Reflux Treatment: Omeprazole 20 mg tablet PO once per day for fourteen (14 days). Elevate HOB 10-30 degrees. Eat smaller, more frequent (4-6x/day) meals Follow-up at end of omeprazole treatment to discuss symptoms and if further studies or treatment is necessary. Direct pharmacy to divide prescription so that the four weekend doses are available to father, and HOB should be elevated at both households. Avoid large, weekend meals. Patient is given a small tablet with dates to record number of times he feels pain or discomfort, or to draw a “smiley face” if there was no pain. Parents may remind patient, but not fill in tablet. GER Journal—Each Table Dated with extra spot for smile Symptom Throat Pain Tummy Pain Feeling uncomfortable or sick in any way Yes (number of times) No A little bit (number of times) Gastroesopageal Reflux Pathophysiology GER is caused by a failure of the cardia, or the portion of the stomach attached to the esophagus. In a normal finding, the Angle of His creates a valve that prevents bile, enzymes, and stomach acid from entering the esophagus where they cause pain and inflammation of esophageal tissue. GER Differentials • GERD—damage to esophageal tissue as indicated by a very long duration >3 months (no clinical guidelines), severe symptoms, previous trial of first-line treatment • Ulcer—pain timed consistently before or after meals, Hx of microorganism exposure, sharp UQ or periumbilical pain. • IBS/UC—Lower GI symptoms • Celiac Disease—previous first-line treatment failures, other systemic symptoms • Abdominal Mass—palpation, constant or severe symptoms, first-line treatment failure • Asthma/UA Disease—primarily respiratory symptoms • Functional Abdominal Pain—careful social, toileting, dietary, and medical history Childhood GER Epidemiology It is estimated that as many as 2 million US children may suffer from GER. Risk factors include an infant history of reflux, family history of reflux, obesity, low activity, chronic disease like Down’s or CF, hiatal hernia, GI tract structural abnormalities including those that are repaired, prematurity, and possibly poor sleep and/or diet. Rudolph, C., Mazur, L., Liptak, G., Baker, R., Boyle, J., Colletti, R., ,…Werlin, S. (2001). Guidelines for evaluation and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 32 Suppl 2, S1-31. Objective: Establish clinical guidelines for simple reflux for infants and children according to systemic review of literature. Results: There is no gold standard for the diagnosis of reflux in children, and a comprehensive history and physical exam are still the best tools. There is an array of effective first-line treatment for reflux to consider before child is evaluated for GERD with upper GI studies. Treatment should be based on history. Conclusions: H2 blockers, PPIs, motility regulators all demonstrated effectiveness in children with GER. Best effectiveness seems to be correlated with history. Systemic review does not suggest clear guidelines for treatment failure, though persistent symptoms after first-line pharmacological treatment do suggest failure. Supportive treatment like increased HOB, smaller meals, and increased activity are palliative. Tighe, MP.; Afzal, NA.; Bevan, A.; Beattie, RM. “Current pharmacological management of gastro-esophageal reflux in children: an evidence-based systematic review.” Paediatric Drugs, v. 11 issue 3, 2009, p. 185-202. Objective: Evaluate pharmacological management of GER in children (excludes infants). Results: H2 blockers, PPI, and motility regulators all demonstrate effectiveness. Antacids are equivocal in their effectiveness. Conclusions: H2 blockers have the longest clinical history and demonstrated effectiveness and safety as first-line treatment for GER. PPIs have emerged as demonstrating a similar, higher compliance treatment and may be more effective for reflux due to h. pylori infection. Motility regulators should be considered after failures of an acid reducer or by history. Romano, C., et al. “Proton pump inhibitors in pediatrics: evaluation of efficacy in GERD therapy.” Current Clinical Pharmacology, v. 6 issue 1, 2011, p. 41-7. Objectives: To evaluate effectives of PPIs as efffective treatment in childhood GER. Results: PPIs are safe and effective for the treatment of childhood GER and slightly more effective than H2 blockers in the treatment of GERD. Conclusions: PPIs should be considered in a childhood diagnosis of GER. Shorter treatment and fewer daily doses may be related to higher compliance. Previously used in confirmed cases of GERD, PPIs are also effective for GER. North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) GUIDELINES Diagnosis: Complete patient and family history, complete symptom history, complete medical (including infant) history, physical symptoms including UQ or periumbilical pain, vomiting, oropharnyx pain, weight loss, heartburn, UR symptoms, recurrent AOM or U/L RI, and dental erosion. Always consider surpaesophageal symptoms. For severe symptoms or pharmacological failure consider ordering an upper GI film, an endoscopic study, or a pH probe study. Treatment: First Class (H2 Blockers) • cimetidine (Tagamet) • ranitidine (Zantac) • famotidine (Pepcid) • nizatidine (Axid) • esomeprazole (Nexium) • omeprazole (Prilosec) • lansoprazole (Prevacid) Third Class (prokinetic agents) • metoclopramide (Reglan) • cisapride (Propulsid) Consider Also: • Have your child eat more frequent smaller meals. • Have your child avoid eating 2 to 3 hours before bed. • Raise the head of your child's bed 6 to 8 inches • Have your child avoid carbonated drinks, chocolate, caffeine, and foods that are high in fat or contain a lot of acid (citrus fruits) or spices. Critique of Care Patient History: Patient history focused on symptoms, familial and infant history, as well as supraesophageal symptoms. Patient Physical: Ruled out most likely differentials. Symptom severity or duration did not rise to the level of ordering studies. Patient Treatment: Ranitidine used more often as first-line, but given Barnard considerations that may impact compliance, as well as paternal history, omeprazole was an excellent choice. Supportive care suggested was appropriate for this child, and journal addressed other Barnard considerations and may also rule out functional abdominal pain. References Gibbons, TE.; Gold, BD. “The use of proton pump inhibitors in children: a comprehensive review.” Paediatric Drugs, v. 5 issue 1, 2003, p. 25-40. Romano, C., et al. “Proton pump inhibitors in pediatrics: evaluation of efficacy in GERD therapy.” Current Clinical Pharmacology, v. 6 issue 1, 2011, p. 41-7. Rudolph, C., Mazur, L., Liptak, G., Baker, R., Boyle, J., Colletti, R., Werlin, S. (2001). Guidelines for evaluation and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 32 Suppl 2, S1-31. Tighe, MP.; Afzal, NA.; Bevan, A.; Beattie, RM. “Current pharmacological management of gastro-esophageal reflux in children: an evidence-based systematic review.” Paediatric Drugs, v. 11 issue 3, 2009, p. 185-202. Gastroesophageal Reflux in Children and Adolescents U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES National Institutes of Health NIH Publication No. 06–5418 August 2006, Retrieved 11/5/2011 from http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/gerinchildren/gerinchildren.pdf

![Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux [10/29/2012]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006891937_1-0f6e6daf80afae340b7d2470e47ece6c-300x300.png)