1. Previewing: Look “around” the text before you start

advertisement

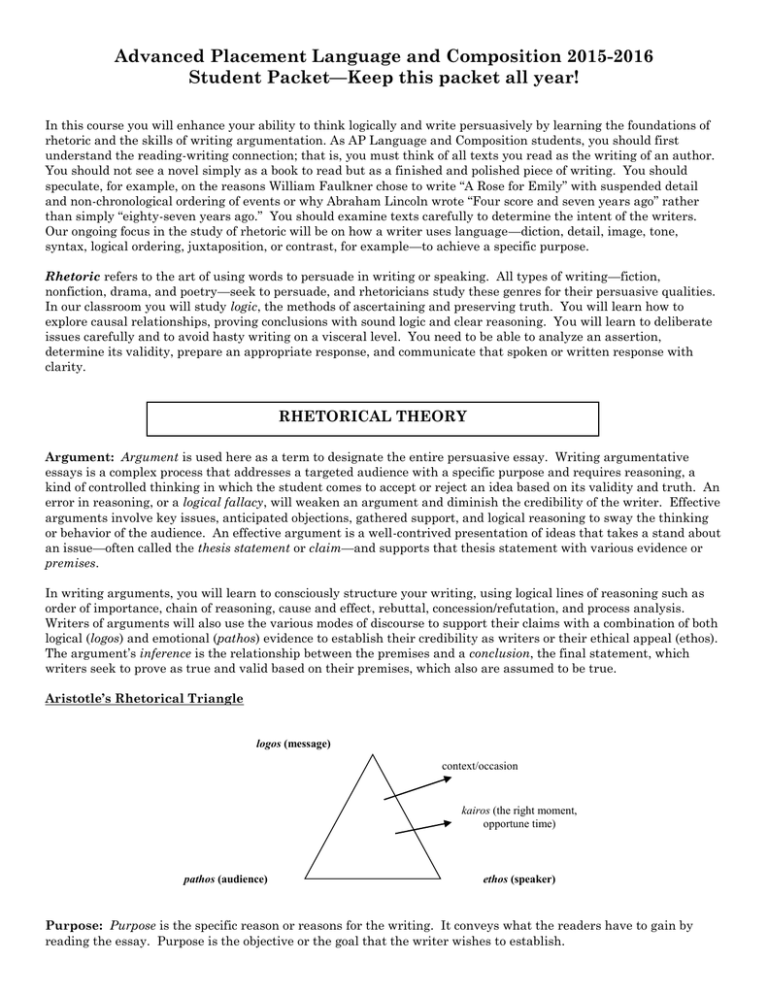

Advanced Placement Language and Composition 2015-2016 Student Packet—Keep this packet all year! In this course you will enhance your ability to think logically and write persuasively by learning the foundations of rhetoric and the skills of writing argumentation. As AP Language and Composition students, you should first understand the reading-writing connection; that is, you must think of all texts you read as the writing of an author. You should not see a novel simply as a book to read but as a finished and polished piece of writing. You should speculate, for example, on the reasons William Faulkner chose to write “A Rose for Emily” with suspended detail and non-chronological ordering of events or why Abraham Lincoln wrote “Four score and seven years ago” rather than simply “eighty-seven years ago.” You should examine texts carefully to determine the intent of the writers. Our ongoing focus in the study of rhetoric will be on how a writer uses language—diction, detail, image, tone, syntax, logical ordering, juxtaposition, or contrast, for example—to achieve a specific purpose. Rhetoric refers to the art of using words to persuade in writing or speaking. All types of writing—fiction, nonfiction, drama, and poetry—seek to persuade, and rhetoricians study these genres for their persuasive qualities. In our classroom you will study logic, the methods of ascertaining and preserving truth. You will learn how to explore causal relationships, proving conclusions with sound logic and clear reasoning. You will learn to deliberate issues carefully and to avoid hasty writing on a visceral level. You need to be able to analyze an assertion, determine its validity, prepare an appropriate response, and communicate that spoken or written response with clarity. RHETORICAL THEORY Argument: Argument is used here as a term to designate the entire persuasive essay. Writing argumentative essays is a complex process that addresses a targeted audience with a specific purpose and requires reasoning, a kind of controlled thinking in which the student comes to accept or reject an idea based on its validity and truth. An error in reasoning, or a logical fallacy, will weaken an argument and diminish the credibility of the writer. Effective arguments involve key issues, anticipated objections, gathered support, and logical reasoning to sway the thinking or behavior of the audience. An effective argument is a well-contrived presentation of ideas that takes a stand about an issue—often called the thesis statement or claim—and supports that thesis statement with various evidence or premises. In writing arguments, you will learn to consciously structure your writing, using logical lines of reasoning such as order of importance, chain of reasoning, cause and effect, rebuttal, concession/refutation, and process analysis. Writers of arguments will also use the various modes of discourse to support their claims with a combination of both logical (logos) and emotional (pathos) evidence to establish their credibility as writers or their ethical appeal (ethos). The argument’s inference is the relationship between the premises and a conclusion, the final statement, which writers seek to prove as true and valid based on their premises, which also are assumed to be true. Aristotle’s Rhetorical Triangle logos (message) context/occasion kairos (the right moment, opportune time) pathos (audience) ethos (speaker) Purpose: Purpose is the specific reason or reasons for the writing. It conveys what the readers have to gain by reading the essay. Purpose is the objective or the goal that the writer wishes to establish. The writer’s purpose might be to… Support a cause Promote a change Refute a theory Stimulate interest Win agreement Arouse sympathy Provoke anger Audience: The audience is the writer’s targeted reader or readers. The relationship between the writer and the audience is critical. You should consider the kind of information, language, and overall approach that will appeal to a specific audience. Here are some questions you can ask yourself during the prewriting stage of your argumentative essays. Who exactly is the audience? What do they know? What do they believe? What do they expect? How will my audience disagree with me? What will they want me to address or answer? How can I—or should I—use jargon? Should I use language that is formal, factual, and objective, or familiar, anecdotal, and personal? Rhetorical Strategies: Appeals of Logic, Emotion, and Ethics Logical Appeals (logos): Incorporate inductive reasoning Use of deductive reasoning Create a syllogism Cite traditional culture Cite commonly held beliefs Allude to history, the Bible, great literature, or mythology Manipulate the style Employ various modes of discourse for specific effects Provide testimony Draw analogies/create metaphors Emotional Appeals (pathos): Develop non-logical appeals Use language that involves the senses Include a bias or prejudice Include connotative language Ethical Appeals (ethos) Show written voice in the argument Make audience believe writer is trustworthy Demonstrate that writer put in research time Support reasons with appropriate, logical evidence Present a carefully crafted and edited argument Order chronologically Provide evidence Classify evidence Use testimony Cite authorities Quote research Use facts Theorize about cause and effect Argue from precedent Explore the euphemism Use figurative language Develop tone Experiment with informal language Demonstrate writer knows & respects audience Show concern about communicating with audience Convince the audience that the writer is reliable & knowledgeable Logical Fallacies Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that render an argument invalid. General guidelines for student writers: 1. Do not claim too much! No writing will completely solve or even fully address all problems involved in a complex topic. 2. Do not oversimplify complex issues. You selected your topic because it is controversial and multifaceted. If you reduce the argument to simplistic terms and come up with an easy solution, you will lose your credibility and diminish your ethos. 3. Support your argument with concrete evidence and specific proposals, not with abstract generalizations and familiar sentiments. Always assume that your audience is skeptical, expecting you to demonstrate your case reasonably, without bias or shallow development. Ten+ Common Logical Fallacies (there are many more!) 1. ad hominem fallacy--“To the individual,” a person’s character is attacked, instead of the argument. Example: Nick Jacobson is not a worthy candidate for vice-president of the senior class because he is short and frowns too much. 2. ad populum fallacy—“To the crowd,” a misconception that a widespread occurrence of something is assumed to make an idea true or right. Example: The parents of Brittany’s friends allow their daughters to stay out until 2:00 a.m. on a school night, so Brittany’s parents should allow her to stay out until 2:00 as well. 3. begging the question—Taking for granted something that really needs proving. Example: “Free all political prisoners” begs the question of whether some of those concerned have committed an actual crime like blowing up the chemistry building in a political protest.” * 4. circular reasoning—Trying to prove one idea with another idea that is too similar to the first idea; such logical ways move backwards in its attempt to move forward. Example: The nuns are not influential because they rarely try to influence (Rep. Bart Stupak to MSNBC’s Chris Matthews). 5. either/or reasoning—The tendency to see an issue as having only two sides Example: The possession of firearms should be completely banned or completely legal. 6. hasty generalization—Drawing a general and premature conclusion on the basis of only one or two cases. Example: The Dallas Police Chief suggested that all dogs be muzzled because two golden retrievers have been disturbing the peace in Fritz Park. 7. non sequitur—“It does not follow,” an inference or conclusion that does not follow from established premises or evidence. Example: “He is certainly sincere; he must be right.” OR “He’s the most popular: He should be president.” 8. pedantry—A display of narrow-minded and trivial scholarship; an arbitrary adherence to rules and forms. Example: Mary prides herself in knowing so much about grammar, but she never earns high grades on essays because she cannot think of insightful ideas or organize her essays. . 9. post hoc, ergo propter hoc--“After this, therefore because of this,” assuming that an incident that precedes another is the cause of the second incident. Example: Han-Hui worked on his written argument longer than he had for any other essay; therefore, he felt he must earn an “A.” 10. propaganda—Writing or images that seek to persuade through emotional appeal rather than through logical proof; written or visual texts that describe or depict using highly connotative words or images—favorable or unfavorable—without justification. Example: Chris’s infatuation with the model’s ruby red lips, beautiful teeth, sparkling eyes, and streaming hair made him believe that Crest White is the best toothpaste. 11. false analogy—A fallacy in which an argument is based on misleading, superficial, or implausible comparisons. “If ObamaCare passes, that free insurance card that’s in people’s pockets is gonna be as worthless as a Confederate dollar after the War Between The States—the Great War of Yankee Aggression.” (Paul Broun (RGA)) *Baker, Sheridan. The Practical Stylist With Readings. 8th Edition. New York: Longman, 1998. Modes of Discourse** Description -- The traditional classification of discourse that depicts images verbally in space and time and arranges those images in a logical pattern, such as spatial or by association. Narration-- The classification of discourse that tells a story or relates an event. It organizes the events or actions in time or relates them in space. Relying heavily on verbs, prepositions, and adverbs, narration generally tells what happened, when it happened, and where it happened. Exposition-- One of the traditional classifications of discourse that has as a function to inform or to instruct or to present ideas and general truths objectively. Exposition can use all of the following organizational patterns. Comparison: This traditional rhetorical strategy is based on the assumption that a subject may be shown more clearly by pointing out ways it is similar to something else. The two subjects may each be explained separately and then their similarities pointed out. Contrast: This traditional rhetorical strategy is based on the assumption that a subject may be shown more clearly by pointing out ways in which it is unlike another subject. Cause and effect: One of the traditional rhetorical strategies, cause and effect consists in arguing from the presence or absence of the cause to the existence or nonexistence of the effect or result; or, conversely, in arguing from an effect to its probable causes. Classification: One of the traditional ways of thinking about a subject; classification identifies the subject as a part of a larger group with shared features. Division: Division is a traditional way of thinking about a subject that includes breaking the subject into smaller segments. Definition: Definition is a traditional pattern of thought which places a subject into an appropriate group and then differentiates the subject from the other sections of the group. The first step limits the meaning of the subject; the second step specifies its meaning. In prose, definitions are often extended by illustrations and examples. Argumentation: Also persuasion. This traditional form of discourse functions by convincing or persuading an audience or by proving or refuting a point of view or an issue. Argumentation uses induction, moving from observations about particular things to generalization, or deduction, moving from generalizations to valid references about particulars, or some combination of the two as its pattern of development. **Woodson, Linda. A Handbook of Modern Rhetorical Terms. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English. 1979. Toulmin Structure of Argument Claim A claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept. This includes information you are asking them to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact. Many people start with a claim, but then find that it is challenged. If you just ask me to do something, I will not simply agree with what you want. I will ask why I should agree with you. I will ask you to prove your claim. This is where grounds become important. Grounds The grounds (or data) is the basis of real persuasion and is made up of data and hard facts, plus the reasoning behind the claim. It is the 'truth' on which the claim is based. Grounds may also include proof of expertise and the basic premises on which the rest of the argument is built. The actual truth of the data may be less than 100%, as all data is based on perception and hence has some element of assumption about it. It is critical to the argument that the grounds are not challenged, because if they are, they may become a claim, which you will need to prove with even deeper information and further argument. Data is usually a very powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical or rational will more likely to be persuaded by data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. It is often a useful test to give something factual to the other person that disproves their argument, and watch how they handle it. Some will accept it without question. Some will dismiss it out of hand. Others will dig deeper, requiring more explanation. This is where the warrant comes into its own. Warrant A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant. The warrant may be explicit or unspoken and implicit. It answers the question 'Why does that data mean your claim is true?' The warrant may be simple and it may also be a longer argument with additional sub-elements, including those described below. Warrants may be based on logos, ethos, pathos, or values that are assumed to be shared with the listener. In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and hence unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded. There are 6 main argumentative strategies via which the relationship between evidence and claim are often established. They have the acronym “GASCAP.” Generalization Analogy Sign Causality Authority Principle These strategies are used at various different levels of generality within an argument, and rarely come in neat packages - typically they are interconnected and work in combination. Backing The backing (or support) to an argument gives additional support to the warrant by answering different questions. Sometimes the warrant is not broadly understood or broadly accepted. In that case, a speaker or writer may have to defend the warrant by backing it up with reasons. Qualifier The qualifier (or modal qualifier) indicates the strength of the leap from the data to the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. They include words such as 'most', 'usually', 'always', 'sometimes'. Arguments may thus range from strong assertions to generally quite floppy or largely and often rather uncertain kinds of statement. Qualifiers and reservations are much used by advertisers who are constrained not to lie. Thus they slip 'usually', 'virtually', 'unless' and so on into their claims. Rebuttal Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counter-arguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through a continued dialogue, or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument. Any rebuttal is an argument in itself, and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing and so on. It also, of course, can have a rebuttal. Thus, if you are presenting an argument, you can seek both possible rebuttals and also rebuttals to the rebuttals. Interrogating Texts: 6 Reading Habits to Develop in Your First Year at Harvard§ Critical reading—active engagement and interaction with texts—is essential to your academic success at Harvard, and to your intellectual growth. Research has shown that students who read deliberately retain more information and retain it longer. Your college reading assignments will probably be more substantial and more sophisticated than those you are used to from high school. The amount of reading will almost certainly be greater. College students rarely have the luxury of successive re-readings of material, either, given the pace of life in and out of the classroom. While the strategies below are (for the sake of clarity) listed sequentially, you can probably do most of them simultaneously. They may feel awkward at first, and you may have to deploy them very consciously, especially if you are not used to doing anything more than moving your eyes across the page. But they will quickly become habits, and you will notice the difference—in what you “see” in a reading, and in the confidence with which you approach your texts. 1. Previewing: Look “around” the text before you start reading. You’ve probably engaged in one version of previewing in the past, when you’ve tried to determine how long an assigned reading is (and how much time and energy, as a result, it will demand from you). But you can learn a great deal more about the organization and purpose of a text but taking note of features other than its length. Previewing enables you to develop a set of expectations about the scope and aim of the text. These very preliminary impressions offer you a way to focus your reading. For instance: What does the presence of headnotes, an abstract, or other prefatory material tell you? Is the author known to you, and if so, how does his (or her) reputation or credentials influence your perception of what you are about to read? If unknown, has an editor helped to situate the writer (by supplying brief biographical information, an assessment of the author’s work, concerns, and importance)? How does the disposition or layout of a text prepare you for reading? Is the material broken into parts-subtopics, sections, or the like? Are there long and unbroken blocks of text or smaller paragraphs or “chunks” and what does this suggest? How might the layout guide your reading? Does the text seem to be arranged according to certain conventions of discourse? Newspaper articles, for instance, have characteristics that you will recognize; textbooks and scholarly essays are organized quite differently from them, and from one another. Texts demand different things of you as you read, so whenever you can, register the type of information you’re presented with. 2. Annotating: “Dialogue” with yourself, the author, and the issues and ideas at stake. From start to finish, make your reading of any text thinking-intensive. First of all: throw away the highlighter in favor of a pen or pencil. Highlighting can actually distract from the business of learning and dilute your comprehension. It only seems like an active reading strategy; in actual fact, it can lull you into a dangerous passivity. Mark up the margins of your text with WORDS: ideas that occur to you, notes about things that seem important to you, reminders of how issues in a text may connect with class discussion or course themes. This kind of interaction keeps you conscious of the REASON you are reading and the PURPOSES your instructor has in mind. Later in the term, when you are reviewing for a test or project, your marginalia will be useful memory triggers. Develop your own symbol system: asterisk a key idea, for example, or use an exclamation point for the surprising, absurd, bizarre . . .. Like your marginalia, your hieroglyphs can help you reconstruct the important observations that you made at an earlier time. And they will be indispensable when you return to a text later in the term, in search of a passage, an idea for a topic, or while preparing for an exam or project. Get in the habit of hearing yourself ask questions—“what does this mean?” “why is he or she drawing that conclusion?” “why is the class reading this text?” etc. Write the questions down (in your margins, at the beginning or end of the reading, in a notebook, or elsewhere. They are reminders of the unfinished business you still have with a text: something to ask during class discussion, or to come to terms with on your own, once you’ve had a chance to digest the material further, or have done further reading. 3. Outline, summarize, analyze: take the information apart, look at its parts, and then try to put it back together again in language that is meaningful to you. The best way to determine that you’ve really gotten the point is to be able to state it in your own words. Outlining the argument of a text is a version of annotating, and can be done quite informally in the margins of the text, unless you prefer the more formal Roman numeral model you may have learned in high school. Outlining enables you to see the skeleton of an argument: the thesis, the first point and evidence (and so on), through the conclusion. With weighty or difficult readings, that skeleton may not be obvious until you go looking for it. Summarizing accomplishes something similar, but in sentence and paragraph form, and with the connections between ideas made explicit. Analyzing adds an evaluative component to the summarizing process—it requires you not just to restate main ideas, but also to test the logic, credibility, and emotional impact of an argument. In analyzing a text, you reflect upon and weigh in on how effectively or how sloppily its argument has been made. Questions to ask: What is the writer asserting is true or valid (that is, what is he or she trying to convince me of? What am I being asked to believe or accept? Why should I accept the writer’s claim(s) as true or valid? Or, conversely, why should I reject the writer’s claim(s)? What reasons or evidence does the author supply me, and how effective is the evidence? What is fact? And what is opinion? Is there anywhere that the reasoning breaks down? Are there things that do not make sense? 4. Look for repetitions and patterns: These are often indications of what an author considers crucial and what he expects you to glean from his argument. The way language is chosen or used can also alert you to ideological positions, hidden agendas or biases. Be watching for: Recurring images Repeated words, phrases, types of examples, or illustrations Consistent ways of characterizing people, events, or issues 5. Contextualize: After you’ve finished reading, put the reading in perspective. When was it written or where was it published? Do these factors change or otherwise affect how you view a piece? Also view it through the lens of your own experience. Your understanding of the words on the page and their significance is always shaped by what you have come to know and value from living in a particular time and place. 6. Compare and Contrast: Fit this text into an ongoing dialogue At what point in the term does this reading come? Why that point, do you imagine? How does it contribute to the main concepts and themes of the course? How does it compare (or contrast) to the ideas presented by texts that come before it? Does it continue a trend, shift direction, or expand the focus of previous readings? How has your thinking been altered by this reading or how has it affected your response to the issues and themes of the course? §Source: Harvard College Library, http://hcl.harvard.edu/research/guides/lamont_handouts/interrogatingtexts.html#top Strategies for Effective Analytical Reading in AP English Use these questions to get you started in your analysis of readings for class. As the semester goes on and you are used to more in-depth thinking, you will add questions. Think of this as a working document. 1. What is the text about? To answer this question, you need to: Take notes For each paragraph, list a word or phrase that identifies the point of the paragraph Collect your notes and phrases to create a summary of the piece 2. How is the text structured? To answer this question, you need to: Identify which of the statements function as claims, premises or reasons, evidence, and conclusions Be able to describe the structure or composition of the essay Read for relationships between sentences and paragraphs 3. How would you describe the language of the text? To answer this question, you need to: Examine the syntax, diction, tone, and figures of speech used by the author Be able to describe the effect of each of these elements 4. To whom is the text addressed? How do you know this? To answer this question, you need to: Use historical or contextual evidence to speculate about the intended audience Identify the speaker’s tone 5. What effect does the text have on the reader? To answer this question, you need to: Identify rhetorical strategies used by the author Examine your emotional and intellectual responses to the text Figure out how the rhetorical strategies create the intellectual and emotional effects 6. What is the text arguing? To answer this question, you need to: Put the main points of all the paragraphs together to see what argument emerges Read for implied meaning Read for the relationships between sentences and paragraphs Look at the structure, language, and subject to see how these elements work together to produce an argument 7. Is the text effective at its goal? Why? To answer this question, you need to: Identify the point or argument of the text Consider the rhetorical strategies at work in the text Determine whether the strategies work to supplement the point or argument Patterns for A+ Thesis Statements—AP Language Timed Writings A simple thesis fits into one sentence. More complicated ideas may be broken into two sentences to preserve clarity and avoid awkward syntax. For rhetorical analysis questions: Prompt: “In the following passage from The Great Influenza, an account of the 1918 flu epidemic, author John M. Barry writes about scientists and their research. Read the passage carefully. Then, in a well-written essay, analyze how Barry uses rhetorical strategies to characterize scientific research.” Topic Claim(s) Developer(s) Modifier (optional) Connector Significance Author/text Verb _____adj________ Devices/techniques X Verb Theme/universal idea/tone/attitude/purpose In the excerpt from The Great Influenza, John M. Barry employs rhetorical questions, parallel structure, and figurative language X to characterize scientific research as something far less certain than laymen generally expect. Notes on writing the essay: —In a rhetorical analysis timed writing, if there is irony, ambiguity, or a shift present in the text, be sure to identify it in either the “claim,” “the developer,” or the “significance.” Ex.: In the excerpt from “Birthday Party,” John M. Barry shifts from the concrete to the abstract, employing rhetorical questions, parallel structure, and figurative language to characterize scientific research as something far less certain than laymen generally expect. —Do not simply summarize the passage. You are expected to identify what the writer is saying, how he/she is saying it, and why he/she is saying it that way. —Do not merely list devices. Be sure to explain the function and purpose of those devices as they relate the universal idea/tone/purpose (whatever the prompt is asking). Don’t be thrown by the terminology. “Stylistic devices,” “resources of language,” “literary devices,” “rhetorical devices” and “strategies” are largely interchangeable terms for the same things. For argument questions: Prompt: “For years corporations have sponsored high school sports. Their ads are found on the outfield fence at baseball parks or on the walls of the gymnasium, the football stadium, or even the locker room. Corporate logos are even found on players’ uniforms. But some schools have moved beyond corporate sponsorship of sports to allowing “corporate partners” to place their names and ads on all kinds of school facilities—libraries, music rooms, cafeterias. Some schools accept money to require students to watch Channel One, a news program that includes advertising. And schools often negotiate exclusive contracts with soft drink or clothing companies. Some people argue that corporate partnerships are a necessity for cash-strapped schools. Others argue that schools should provide an environment free from ads and corporate influence. Using appropriate evidence, write an essay in which you evaluate the pros and cons of corporate sponsorship for schools and indicate why you find one position more persuasive than the other.” Topic Claim(s) Developer(s) Controversial subject Position Reason(s) Modifier (optional) Connector (optional) Significance (optional) Qualifiers/limiters/exceptions Conjunction/transition Consequence/relevance/ benefit/result Corporate advertisements in public schools are appropriate and even desirable in order to provide much needed funding and create a realistic educational environment, as long as corporations don’t control the curriculum. This will allow schools to purchase the latest equipment and students to be better prepared for life as wary adult consumers. Notes on writing the essay: —Be sure to provide evidence for all assertions. —Be sure to display maturity by taking your opponents’ perspectives and concerns into account. This would include offering reasonable rebuttals to their arguments to show you have considered them. For synthesis questions: The most common types of synthesis questions are persuasive and expository. If you are asked to take a position, you can use the pattern provided above for persuasive topics. If you are asked to write an expository essay (“Identify key issues and their implications,” “evaluate the most important factors,” etc.), use the pattern below. “Key Issues” Prompt: “Locavores are people who have decided to eat locally grown or produced products as much as possible. With an eye to nutrition as well as sustainability (resource use that preserves the environment, the locavore movement has become widespread over the past decade. Imagine that a community is considering organizing a locavore movement. Carefully read the following seven sources, including the introductory information for each source. Then synthesize information from at least three of the sources and incorporate it into a coherent, well-developed essay that identifies the key issues associated with the locavore movement and examines their implications for the community.” Developer(s) Controversial subject Adjective + noun + verb (from prompt) Issues/influences/factors Modifier (optional) Connector (optional) Significance (optional) Qualifiers/limiters/exceptions Conjunction/transition Consequence/relevance/ benefit/result Topic Claim(s) When a community considers organizing a locavore movement, the key issues to consider are (adj) (noun) (verb) affordability for the average family, sustainability of the program, and the impact on the local economy. As long as organizers don’t focus on price alone, a locavore program can raise the standard of living for everyone in the long term. “Position” Prompt: “The United States Postal Service (USPS) has delivered communications for more than two centuries. During the nineteenth century, the USPS helped to expand the boundaries of the U.S. by providing efficient and reliable communication across the country. Between 1790 and 1860 alone, the number of post offices in the U.S. grew from 75 to over 28,000. With this growth came job opportunities for postal workers and a boom in the cross-country rail system. The twentieth century brought substantial growth to the USPS, including large package delivery and airmail. Over the past decade, however, total mail volume has decreased considerably as competition from electronic mail and various package delivery companies has taken business away from the USPS. The loss of revenue has prompted the USPS to consider cutting back on delivery days and other services. Carefully read the following seven sources, including the introductory information for each source. Then synthesize information from at least three of the sources and incorporate it into a coherent, well-developed essay that argues a clear position on whether the USPS should be restructured to meet the needs of a changing world, and if so, how.” Connector (optional) Significance (optional) Conjunction/transition Consequence/relevance/ benefit/result Topic Controversial subject Modifier (optional) Qualifiers/limiters/exceptions Claim(s) Adjective + noun + verb (from prompt) Developer(s) Issues/influences/factors In a fast-paced society of sleek innovations and modern new technologies, it can be easy to get lost in the hype of popular new gadgets and trends while, if not forgetting, moving away from the traditions and enterprises that were so vital to the United States as a developing country. The United States Postal Service has become a casualty of the innovation we laud so highly. While we should not discount the progress made in the past decades that has facilitated a transition to faster and sleeker technologies, it is also paramount that we support and maintain traditions and symbols of (adj) (verb) (verb) (noun) (noun) the American dream like the USPS by applying modern principles and revamping the company’s image and organization. Notes on writing the essay: —Do not merely summarize the sources. They should be used to support your argument or exploration of the topic. —ALWAYS use at least THREE of the sources in your essay. —ALWAYS document/cite the sources you use, whether you quote them directly or merely summarize them. —Be sure to display maturity by taking other possible perspectives and concerns into account. Tips for Writing Rhetorical Analysis Timed Writings 1) In your essay, always include the following: What is the writer saying? (What does the prompt ask you about the passage?) How is he/she saying it? (What literary techniques does the writer use to convey his/her ideas? These may also be identified in the prompt by expressions such as “literary devices,” “narrative techniques,” “resources of language,” or some other general label.) Why is he/she saying it that way? (Why are the techniques used particularly appropriate to express the writer’s ideas? What are the connections between form and function?) 2) Remember the following in writing an introduction: Identify the author(s) and title(s). Specifically identify the idea content of the paper. Specifically identify the techniques you will analyze (rhetorical questions, juxtaposition, military imagery, anaphora, etc.). o Poor—“The author conveys her ideas about the subject using many literary techniques.” “The author uses a multitude of literary devices.” “The writer employs various techniques.” o Better—“The writer portrays her experience as painful, but not crippling.” “Annie Dillard employs asyndeton and musical imagery to humanize the normally esoteric subject of genetics.” “The author applies rhetorical questions, juxtaposition, and agrarian imagery to…” Don’t waste time on an elaborate intro, but don’t begin in the middle of a thought. Get to the point, but set it up smoothly. o Poor because it’s underdone and vague—“In the passage provided, Capote paints a vivid picture in the reader’s mind.” “He uses tone and structure to help the reader grasp his point.” o Poor because it’s overdone and fawning (stop cheerleading!)—“Since the dawn of human history, mankind has feared the darkness. What mystical dangers lurked just beyond the boundary between sun and shadow? In fear and superstition, we invented dark gods, spirits, and demons to personify this primary terror. As our ancestors wrestled with their perceptions of evil, both rational and irrational, superstition evolved into religion, religion transformed into philosophy, and philosophy metamorphosed into the complex moral and ethical systems by which we live today. It is all too natural for human beings, as slaves to these illusory and artificial systems of morality, to misperceive the true threat. While societies around the globe eternally look for the source of evil to the outside, the foreign, the “other”, Truman Capote understands that the true nature of evil lies within each of us. Our safe and comfortable world, ruled by the repetition of the mundane, is, in fact, subject at any moment to a devastating assault of evil. This assault may come, not from an obvious and distant villain, but from the most unlikely of individuals, a tortured soul that has lost his inner battle between the ever-combative forces of good and evil. Capote’s brilliant documentary novel, In Cold Blood, fully explores this moral horror. The passage provided is from the opening of the book, and in it Capote masterfully sets the stage for his disturbing tale using a plethora of exquisitely chosen tools of language.” (I’m exhausted just reading that!) o Adequate, but minimal—“In the opening passage of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, the writer portrays the small town of Holcomb. Through his control of structure, detached tone, and meaningful choice of detail, he makes it clear that the town appears to be ordinary, despite its horrible history.” o Better—“In Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, the writer portrays a town that is apparently very ordinary. Nothing and no one stops in this unremarkable little community. However, the final lines of the passage imply that something very unordinary will soon be revealed, and that the reader can expect to see this bland scene in a new light. Capote employs anaphora, parenthetic expressions, a detached tone, and significant details to emphasize Holcomb’s blandness and to hint at the drama to come. 3) Make specific references to the text(s). Quote where feasible; use line numbers or paragraph numbers to refer to lengthy sections. Integrate quotes smoothly with your own text. Use transitional phrases (“the author states…” “Angier writes…”) and brackets when you need to make a change within the quote itself (The speaker challenges the opposition, saying that, “[they] don’t know what [they’re] doing.” —the original read, “You don’t know what you’re doing.”) o Poor because the quote sits alone without connection to the writer’s analysis—“The earth developed like a living thing. Time is speeded up. “The ice rolled up; the ice rolled back.” o Better—“The earth may seem unchanging, but the writer captures the moving cycle of nature when she collapses thousands of years of time into two simple clauses, saying, “The ice rolled up; the ice rolled back.” 4) Concentrate on analysis, not summary. Assume that your audience has read the piece. Don’t spend too much time summarizing plot, but provide enough details to support your contentions. o Poor/TMS—“Nothing stops in Holcomb: not the river, or the cars, or the trains. The post office is falling apart. No one can even buy alcohol here. o Better—In a series of similes—“[l]ike the waters of the river, like the motorists on the highway, and like the yellow trains streaking down the Santa Fe tracks, drama…had never stopped there”—Capote captures the ordinariness of Holcomb. This juxtaposition of an impersonal natural force (the river) with the human elements of cars and trains emphasizes the blandness of Holcomb. Drivers and engineers have the choice to stop their vehicles, but Capote implies that the town is so dull that they must bypass the town, just as the water must continue downstream. Additionally, the use of anaphora evident in the repetition of “like” creates a compounding effect. The list emphasizes the magnitude of Holcomb’s uninteresting nature. Nothing stops in Holcomb. 5) Make connections between form and function (but don’t use those words in your essay). This is the essence of the style analysis essay. Always point out the significance or effect of the techniques you identify—the more specific and insightful the connection, the better. Poor/superficial Poor/unspecified/unexplained Poor/invalid Better The author uses first person to help the reader see the character’s ideas. The author uses imagery to place a picture in the reader’s mind. First person point of view allows her to tell the story. The differences show a contrast between the town and the farm. The writer uses imagery to describe how the speaker feels. Capote uses sensory detail to see what is to be seen and hear what is to be heard. The signs and even the buildings, such as the mansion and the train depot, are falling apart (why is this significant? why choose these details?). Dillard uses personification to represent the mangroves (why is “personification” especially appropriate here?). Flashbacks help set the tone of the essay. Flashbacks prove the speaker is depressed (also psychobabble). The tone is ambiguous since the speaker’s gender is not specified. The anaphora shows how the speaker feels about his experience. Repetition emphasizes the author’s… Repetition links the opening paragraph with the conclusion by…. The central metaphor of decaying buildings conveys the moral decay of the community. The metaphor of the lock and key is appropriate because the lock mirrors the closed nature of the daughter’s problems, while the key represents the simplistic attitude of the unseen speaker—he or she assumes that the mother can solve her child’s problems as easily as turning a key. Rhetorical questions reinforce the speaker’s confusion and helplessness, as they are never meant to be answered. 6) Miscellaneous reminders: Use literary present tense (the mother rationalizes her failures…; Holcomb is portrayed as a peaceful town…) Use the most specific terms you can. If you can’t think of a specific one, use a more general expression. o Poor—The writer uses a literary device o Adequate—The writer uses descriptive language to…; questions convey…; the comparison reinforces… o Better—The writer uses military imagery to…; rhetorical questions convey…; the simile reinforces… Note: Never say “uses diction” or “uses syntax.” Diction is word choice and syntax is sentence structure. All writers use words and all sentences have a structure. You are not conveying your insight by saying that. Use an adjective or a phrase to specify the nature of your observation. o Poor—“The writer uses diction to…” “The writer uses syntax to…” o Better—“The writer’s religious diction conveys…” or “The passage contains diction with scientific connotations…” or “The author manipulates her syntax in order to…” or “The writer’s use of parallel sentence structure reflects…” Note: If you find irony, ambiguity, or ambivalence, always point it out. The AP readers eat it up. Don’t fake it, though. That will make the readers throw it up. GAG* Sheet (*Grammar at a Glance) Independent Clause (I) Dependent (D) / subordinate clause: Noun Pronoun Verb Adjective Adverb Conjunction Preposition Interjection Book Magazine Newspaper, Film “Short Story” “Song” “Article” “Essay” *Adjective clause *Adverb clause *Noun clause Prepositions The mouse ran ___ the clock. It is=it’s Possessive it=its Coordinating Conjunctions ADJ N. or PRO. For And Nor ADV V, ADJ. or ADV. But Or Yet So Transitional expressions: as a result, for example, in other words, at any rate, in addition, on the contrary, by the way, in fact, on the other hand Someone left his or her umbrella. Singular subject + singular verb Capitalize Specific names of persons, places, things. Stone Mountain / mountain Atlantic Ocean / ocean President Bush / man Simple - I Compound = I ; I Complex = I+ D Compound-Complex=I + D + I John is going to the office. Plural subject + plural verb John and Mary are going to the office. Adjective Phrase Adverb Phrase A prepositional phrase functioning as an adjective. A prepositional phrase functioning as an adverb. The boys from GHS tried to outrun the opposition. The water splashed along the stream. Possessives Misplaced/Dangling Modifiers -Filling the air with thick smoke, we watched the garage burn. (did we fill the air with smoke?) -Joan bought a new DVD player for the family which never worked well. (did the family or the DVD not work well?) -The car went off the road while trying to read the map. (was the car trying to read the map?) Appositive =placed beside another N to identify or explain it Appositive phrase= appositive + modifiers My Mine Your Yours His Her : (Colon) Their a list Indicates One of the boys left his umbrella. S-V S-V-DO S-V-IO-DO S-V-DO-OC S-LV-PN S-LV PA Who/Whom Nominative=Who/whoever Objective = Whom/whomever Linking Verbs Am Is Are Was Were Interjections- Wow, huh? Shoot, blah! Duh! Subject Predicate DO IO PN PA OP OC Comma D,I. Items in a series City, State After nouns of address I, conjunction I. I, transition I. Gerunds are –ing NOUNS and can do anything a noun is to follow. can do. Spelling is an easy subject. SUBJECT She is proficient in spelling. OP Participles are –ed or –ing ADJECTIVES. -ing indicates a present participle I like swimming. DO -ed (or the past-tense form of the verb indicates a past participle His hobby is singing . PN Mary expects to learn typing. Object of infinitive The dog eating the bone is mine. Modifies dog. A gerund phrase is the gerund and the words that go with Lying in the sun, I got very sleepy. Modifies I it. Running a 5K is especially satisfying. The tall man carrying the briefcase is Mr. Bixby. Modifies man. . ; (Semicolon) -Between two or more independent clauses. I;I. -Between items in a series when there are already commas in the items. Adverb Phrases is a prepositional phrase that functions as an adverb. Prepositional Phrases begin with a preposition and end with a N or PRO. He ran without stopping for 5K. modifies ran Correlative conjunctions Both…and Either…or Neither…nor Not only…but also Subordinating conjunctions After, although, as, as if, as much as, as though, as well as, because, before, even though, how, if, in order that, provided, since, so that, than, that, when , whenever, where, wherever, while, why Adjective Phrase is a prepositional phrase that functions as an adjective. The man with the big hat is wealthy. modifies man Singular subject + singular verb Plural subject + plural Verb Conjunctive adverbs - Also, anyway, besides, consequently, furthermore, however, still, instead, likewise, meanwhile, moreover, nevertheless, then, therefore Tone Vocabulary Like the tone of a speaker’s voice, the tone of a work of literature expresses the writer’s feelings. To determine the tone of a passage, ask yourself the following questions: 1. What is the subject of the passage? Who is its intended audience? 2. What are the most important words in the passage? What connotations do these words have? 3. What feelings are generated by the images of the passage? 4. Are there any hints that the speaker or narrator does not really mean everything he or she says? If any jokes are made, are they lighthearted or bitter? 5. If the narrator were speaking aloud, what would the tone of his or her voice be? Positive Tone/Attitude Words Amiable Consoling Amused Content Appreciative Dreamy Authoritative Ecstatic Benevolent Elated Brave Elevated Calm Encouraging Cheerful Energetic Cheery Enthusiastic Compassionate Excited Complimentary Exuberant Confident Fanciful Friendly Happy Hopeful Impassioned Jovial Joyful Jubilant Lighthearted Loving Optimistic Passionate Peaceful Playful Pleasant Proud Relaxed Reverent Romantic Soothing Surprised Sweet Sympathetic Vibrant Whimsical Negative Tone/Attitude Words Accusing Choleric Aggravated Coarse Agitated Cold Angry Condemnatory Apathetic Condescending Arrogant Contradictory Artificial Critical Audacious Desperate Belligerent Disappointed Bitter Disgruntled Boring Disgusted Brash Disinterested Childish Facetious Furious Harsh Haughty Hateful Hurtful Indignant Inflammatory Insulting Irritated Manipulative Obnoxious Outraged Passive Quarrelsome Shameful Smooth Snooty Superficial Surly Testy Threatening Tired Uninterested Wrathful Humor-Irony-Sarcasm Tone/Attitude Words Amused Droll Bantering Facetious Bitter Flippant Caustic Giddy Comical Humorous Condescending Insolent Contemptuous Ironic Critical Irreverent Cynical Joking Disdainful Malicious Mock-heroic Mocking Mock-serious Patronizing Pompous Quizzical Ribald Ridiculing Sad Sarcastic Sardonic Satiric Scornful Sharp Silly Taunting Teasing Whimsical Wry Source: PAP/AP English Handbook, Grades 9-12 Tone Vocabulary (cont.) Sorrow-Fear-Worry Tone/Attitude Words Aggravated Embarrassed Agitated Fearful Anxious Foreboding Apologetic Gloomy Apprehensive Grave Concerned Hollow Confused Hopeless Dejected Horrific Depressed Horror Despairing Melancholy Disturbed Miserable Morose Mournful Nervous Numb Ominous Paranoid Pessimistic Pitiful Poignant Regretful Remorseful Resigned Sad Serious Sober Solemn Somber Staid Upset Neutral Tone/Attitude Words Admonitory Dramatic Allusive Earnest Apathetic Expectant Authoritative Factual Baffled Fervent Callous Formal Candid Forthright Ceremonial Frivolous Clinical Haughty Consoling Histrionic Contemplative Humble Conventional Incredulous Detached Informative Didactic Inquisitive Disbelieving Instructive Intimae Judgmental Learned Loud Lyrical Matter-of-fact Meditative Nostalgic Objective Obsequious Patriotic Persuasive Pleading Pretentious Provocative Questioning Reflective Reminiscent Resigned Restrained Seductive Sentimental Serious Shocking Sincere Unemotional Urgent Vexed Wistful Zealous Language Words-Used to describe the force or quality of the entire piece Like word choice, the language of a passage has control over tone. Consider language to be the entire body of words used in a text, not simply isolated bits of diction, imagery, or detail. For example, an invitation to a graduation might use formal language, whereas a biology text would use scientific and clinical language. Different from tone, these words describe the force or quality of the diction, images, and details AS A WHOLE. These words qualify how the work is written. Artificial Bombastic Colloquial Concrete Connotative Cultured Detached Emotional Esoteric Euphemistic Exact Figurative Formal Grotesque Homespun Idiomatic Informal Insipid Jargon Learned Source: PAP/AP English Handbook, Grades 9-12 Literal Moralistic Obscure Obtuse Ordinary Pedantic Picturesque Plain Poetic Precise Pretentious Provincial Scholarly Sensuous Simple Slang Symbolic Trite Vulgar AP Caliber Verbs (to use in essays) Practice using a variety of verbs to phrase “said” and “symbolize” in different ways. Avoid using “symbolize” because students find it too easy to write “x symbolizes y” and then neglect to explain or justify with details. show (1 x only) symbolize (1 x only) relay signify develop characterize evoke introduce detail minimize parallels weaken promote writes contributes testifies affirms entails directs support define adds validates dismiss proposes reaffirms render paint tint simplify connect epitomize suggest portray allude describe involves view convey portend maximize corroborate display produces continues cause verifies deters explains compare legitimize enforces detract invalidates justify mislead states comprehend builds understand complicate expresses illustrate imply relate reveal reflect diminish enable establish foreshadow identify refer amplify concludes points affects certifies presents traces contrast deny enhance resembles hint translate guide specify link balances envelops juxtapose parodies demonstrate infer represent discover use draw transmit magnify reiterate correlate strengthen exemplify consider stem effect (verb) vouch marks leads confuse defy reinforce contradict create indicates address complement communicate ascertain evolves combines satirize WORDS TO DESCRIBE SYNTAX plain spare austere unadorned ornate elaborate flowery jumbled chaotic obfuscating erudite esoteric journalistic terse laconic harsh grating mellifluous musical lilting lyrical whimsical elegant staccato abrupt solid thudding sprawling disorganized dry deceptively simple 18 Detractors from Mature Academic Voice 1. Use of first person. Avoid “I think,” “I believe,” “To me this means…” 2. Use of second person “you.” Avoid the use of the second person. No: “when you die…” Instead use: “When humans die…” No: “The slant rhyme makes you notice…” Instead use: “The slant rhyme makes the reader notice.” 3. Colloquial speech and immature, excessively informal vocabulary. Examples: “Your average Joe,” “Joe College,” “Back in the olden days,” “Nowadays,” “A bunch of…a ton of…” (Does the writer mean “a significant number of…”?); “I would have to say…” (Not really); “That would have to be…” (Again, not really) 4. Use of psychobabble: “Pap destroyed Huck’s self-esteem.” “The peer pressure on Hester Prynne,” “Gatsby was depressed by…” “Huck and Jim’s life-style on the raft…” “Virginia Woolf, herself a depressed person, writes a rather bi-polar essay.” 5. Use of absolutes: “always” “never” “everybody” “I’ll bet 99.9% of the people…” 6. Excesses of tone: hysterical, breathless, indignant, self-righteous, cute, breezy, etc. Example: “If a homeless man even talks he gets arrested.” 7. Cheerleading, a special kind of excess of tone when the student lavishes praise on an author or her work. Examples: “The greatest poet…” “Does a magnificent job of…” “so awesome,” “obviously a genius,” “…will affect me for the rest of my life.” (Note: this observation is not intended to squelch true passion or heart-felt response to literature.) 8. Silly, weak, childish examples: students’ lack of discernment with regard to quality examples or evidence; using cartoons, Disney movies, etc. as legitimate evidence. 9. Rhetorical questions, especially those with an indignant response, such as: “Do we Americans have to put up with this? I think not!” 10. Clichés, all of them. They’re as old as the hills. 11. Exclamation points, especially lots of them!!!!!! 12. Most adverbs, such as basically, obviously, surely, certainly, very, really, incredibly, totally, etc. should be used sparingly! 13. Writing about the author or the speaker or narrator as though they are the same. Weak: Dickinson greets death as a courtly suitor. Stronger: Dickinson’s speaker greets Death as a courtly suitor. 14. Misspelling the author’s name! 15. Referring to authors by their first names. Please use “Whitman and Dickinson,” never “Walt and Emily.” 16. Writing about an author’s life rather than his or her work or specific purpose in a text. Weak: “Whitman and Dickinson write about death differently due to their different life experiences.” Better: “Dickinson’s purpose in using this image is…” or “Whitman’s imagery suggests…” 17. Using technical vocabulary incorrectly. Examples: “Green uses emotional syntax.” “She uses dictional phrases like…” “His short fragments are all connected by commas and collaborated into a few run-on sentences.” 18. Gobbledygook, usually some kind of combination of the characteristics listed above. It imitates pretentious writing but says little. Examples: “The author brilliantly uses a hyphen in order to emphasize and reinforce motivation and justice that God provides and installs in each and every man.” “Meger (sic) imagery provided by the author commences to place a precedence (sic) of their style, a conventional rhetoric that gives the passage somewhat of a quixotic tone.” What is “adequate” development? Essay contains a clear thesis statement AND enough specific information to explain your main idea. Content Discussion Support Includes: Examples – particular instances of a general idea or principle – an essay about the best movie of the year might include a discussion of three or four films. Details – small items or pieces of information that make up something larger – an essay about an author might describe details about his or her career. Facts – specific pieces of information that can be verified – an essay about the tone and style of a selection might include quotations. Reasons – explanations, justifications, or causes, often answering the question WHY? about the main idea – an essay advocating gun control might include an explanation of ineffective current laws. Events – incidents or happenings – a travel memoir might include one or two amusing anecdotes. A well developed essay must contain enough support to meet the expectations established by your introduction and thesis statement. In addition, the supporting information must make the essay seem complete. A rule of thumb: If your reader turns the page to look for the rest of your paper, it is not complete! Thoreau advocates “simplify, simplify.” I advocate “specify, specify.” Follow both! MLA Citation Information Here are some guidelines and samples for citing sources and preparing bibliography pages. The MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers by Joseph Gibaldi is the comprehensive MLA tool for students. Two copies of this book are available at the circulation desk. In addition, always ask your teacher or the media staff for help when you do not know how to cite a source. Note: Double space within and between entries Single space after all concluding punctuation marks Alphabetize entries by the author’s last name Indent from 2nd line on in each entry A BOOK BY A SINGLE AUTHOR (5.6.1) Last name, first name of author. Title of the Book. City of publication: Publisher, year of publication. Wormser, Richard L. Three Faces of Vietnam. New York: Franklin Watts, 1993. A BOOK BY TWO OR MORE AUTHORS (5.6.4) Last name, first name, and first name last name. Title of the Book. City of publication: Publisher, year of publication. Simpson, Carolyn, and Mary Hall. Careers in Medicine. New Haven: Rosen Publishing, 1994. AN ENTIRE ANTHOLOGY OR A COMPILATION (5.6.2) Last name, first name, ed. Title of the Anthology. City of publication: Publisher, year of publication. Michelson, Bruce, ed. The Norton Anthology of American Literature. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1998. A WORK IN AN ANTHOLOGY (5.6.7) Last name, first name. “Title of work or chapter.” Title of the Book or Anthology. Ed. Name of editor. City of publication: Publisher, year of publication. Page numbers. Beach, Joseph. “John Steinbeck’s Authentic Characters.” Readings on John Steinbeck. Ed. Clarice Swisher. San Diego: Greenhaven, 1966. 21-24. A BOOK BY A CORPORATE AUTHOR (5.6.6) Name of Corporation. Title of the Book. Ed. Name of editor. City of publication: Publisher, year of publication. American Medical Association. Complete Guide to Women’s Health. Ed. Ramona Slupik. New York: Random House, 1996. AN ARTICLE IN A NEWSPAPER (5.7.5) Last name, first name. “Title of Article.” Title of Newspaper Day Month Year: page numbers+. URL if accessed online. Hulber, Dan. “Disney Rescues a Faded Broadway Star.” The Atlanta Journal-Constitution 25 May 1997: K4+. http://www.ajc.com/. AN ARTICLE IN A MONTHLY PERIODICAL (5.7.6) Last name, first name. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine Month Year: page numbers. URL if accessed online. Vizard, Frank. “Electric Tales.” Popular Science June 1997: 57-59+. http://www.popsci-magazine.com. AN ARTICLE IN A WEEKLY PERIODICAL (5.7.6) Last name, first name. “Title of Article.” Title of Magazine Day Month Year: page numbers. URL if accessed online. Jaroff, Leon. “Etched in Stone.” Time 2 June 1997: 67-70. http://www.time.com/time/. AN ARTICLE IN A SCHOLARLY JOURNAL (5.7.1) Last name, first name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal Volume.Issue (Year): pages. Sipe, Rebecca. “Grammar Matters.” English Journal 95.5 (2006): 15–17. http://www.ncte.org/journals/ej. AN ARTICLE IN A REFERENCE BOOK (5.6.8) Last name, first name. “Title of Article.” Title of Reference Book. Edition (if available). City of Publication: Publisher, year of publication. Maxwell, Sam. “Joseph Conrad.” Contemporary Literary Criticism. Detroit: Gale, 1982. “Baseball.” The World Book Encyclopedia. Chicago: World Book, Inc., 2000. PERSONAL INTERVIEW (5.8.7) Last name, first name of person interviewed. Interview type. Day Month Year of interview. Smith, Sue. Personal interview. 20 June 1996. AN ENTIRE INTERNET SITE (5.9.2) Title of Website. Ed. Name editor (if given). Date of latest update. Name of sponsoring institution. Day Month Year of access <URL>. Major Biomes of the World. Ed. Susan Woodward. July 1997. The Virtual Geography Department at Radford University. 14 August 2006. http://www.runet.edu/~swoodwar/CLASSES/GEOG235/biomes/main.html. A PAGE ON A WEBSITE (5.9.1) Last name, first name of author. “Title of Page.” Title of Website. Date of latest update. Name of sponsoring institution. Day Month Year of access <URL>. Conrey, Sean. “Literary Terms.” The Owl at Purdue. February 2006. The Writing Lab at Purdue University. 16 August 2006. http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/575/01/. AN ARTICLE FROM AN ELECTRONIC DATABASE (5.9.7) Last name, first name of author and/or editor. “Title of Article.” Title of publication (in italics). Volume.issue # (publication date): Page #s, if available, (n. pag., if no page #s). Publisher information (i. e., name of database service). Day month year material accessed. Vail, Kathleen. “Columbine: 10 Years Later.” American School Board Journal 196.5 (May 2009): 16-23. Academic Search Complete. Web. 31 Jan. 2011. A SOUND RECORDING (5.8.2) Name of Artist. “Name of Song.” Name of Album. Label, Year. Coldplay. “The Scientist.” A Rush of Blood to the Head. Capital, 2002. For more information, consult: MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers by Joseph Gibaldi http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/557/01/ WRITING AND ASKING QUALITY QUESTIONS FOR CLASS DISCUSSION Questions and Reading: As you read, you should write down questions about the beliefs, ethics, and motivations of the characters; the values the narrator is trying to convey; the themes being developed; and the language (diction, syntax, detail) the author uses to convey those ideas. Guidelines for questions: Create the specified number of good questions. Do not write questions that can be answered “yes” or “no” Do not write questions that can be answered with only a few words Do not write answers to your questions Do not write questions that can be answered with simple facts Do not write questions that are so general that they could apply to any story or character DO write “why” and “how” questions DO write questions about details that confuse you or make you wonder DO write questions about literary elements, diction, syntax, and detail Sample questions (from “The Black Cat”): Low-quality questions Did the narrator like his cat? (yes or no) What did the narrator do to his wife? (fact) How does the author use diction? (too general) What are the connotations of the word “thrilled”? (answer requires only a few words) High-quality questions Why does the narrator feel the cat was crushing him as he slept? How does the writer’s syntax convey the narrator’s mental state during the confrontation scene with the police? Why does the narrator adopt the second cat? Guidelines for Participants in a Socratic Discussion Refer to the text when needed during the discussion. A seminar is not a test of memory. You are not “learning a subject;” your goal is to understand the ideas, issues, and values reflected in the text. Use specific evidence from the text to support your opinions. Do not participate on topics for which you are not prepared. A seminar should not be a bull session. Do not stay confused; ask for clarification. Stick to the point currently under discussion; make notes about ideas you want to come back to. Don’t raise hands; take turns speaking. Listen carefully and respond to others with respect for their observations. Speak up so that all can hear you. Talk to each other, not just to the leader or teacher. Discuss ideas rather than each other’s opinions. YOU are responsible for the seminar, even if you don’t know it or admit it. Do not be an intellectual parasite; contribute to the discussion for more than just getting a better grade. Address other students, not the teacher. Sample questions that demonstrate constructive dialogue rather than debate: Why is line 8 so confusing? What is the purpose of all that boring description at the beginning of chapter 14? Here is my view and how I arrived at it. How does it sound to you? What gaps in my reasoning can you see? What kind of different data do you have? How are your conclusions different from mine? How did you arrive at your view? What are you taking into account that’s different from what I have considered? Can somebody explain the allusion to Hamlet on page 76? Why does the writer keep repeating the word “cold”? DIDLS Title: __________________________________________ NAME(S) ____________________________________ Page #s: _________________, starting at _____________________________ and ending ___________________ D The author’s choice of words and their connotations—What words appear to have been chosen specifically for their effects? What effect do these words have on your mood as the reader? What do they seem to indicate about the author’s tone? I The use of descriptions that appeal to sensory experience— What images are especially vivid? To what sense do these appeal? What effect do these images have on your mood as a reader? What do they seem to indicate about the author’s tone? D Facts included or those omitted—What details has the author specifically included? What details has the author apparently left out? What effect do these included and excluded details have on your mood as a reader? What do these included and excluded details seem to indicate about the author’s tone? L Characteristics of the body of words use (slang, jargon, scholarly language, etc.)—How could the language be described? How does the language affect your mood as a reader? What does the language seem to indicate about the author’s tone? S The way the sentences are constructed—Are the sentences simple, compound, declarative, varied, etc.? How do these structures affect your mood as a reader? What do these structures seem to indicate about the author’s tone? Is the emphasis on nouns or verbs? What effect does this have? SOAPSTone Text Title:___________________________________ Beginning at __________ and ending at ___________ Speaker –Who is the voice that is speaking and what rhetorical devices does he use – style? • The voice that is speaking. Identification of the historical person (or group of people) who created the primary source. What attributes identify the speaker? Speaker’s perspective and relationship to the text affect how text is perceived • What do we know about this historic or contemporary person? • What role does he play in an historic event? Occasion– What event or catalyst initiated writing? • What is the time and place, the context in which the primary source was created? • What is the geographic and historic intersection at which this source was produced? Audience—To whom is the piece directed? • Is the writing intended to challenge a predicted point of view? To build on a predicted shared point of view? • Is the audience a peer group? Superiors? Other? • Are there both intended and unintended audiences? Purpose – What is the reason behind text? • Why was it written? What goal did the author have in mind? • What is the reader supposed to think or do as a result of reading/hearing this? Subject – What is the general topic or main idea? • State the subject in a few words or phrases Tone – What is the attitude of author toward the subject? • Examine the choice of words, emotions expressed, imagery, etc., (DIDLS) used to determine the speaker’s attitude. commentary specific; well organized; strong evidence; precise language insufficient analysis; doesn’t rise above ordinary; some summary; lacks deep perceptions; simple analysis at times Low…attempts to discuss topic; some relevant points; unfocused or vague at times. High…concise, articulate; Medium…accurate points; some Rhetorical Analysis Rubric 9 Essays earning a score of 9 meet the criteria for a score of 8 and, in addition, are especially sophisticated in their argument, thorough in their development, or impressive in their control of language. 8 Effective Essays earning a score of 8 effectively analyze* how Capote uses rhetorical strategies to convey his message. They develop their analysis with evidence and explanations that are appropriate and convincing, referring to the passage explicitly or implicitly. The prose demonstrates a consistent ability to control a wide range of the elements of effective writing but is not necessarily flawless. 7 Essays earning a score of 7 meet the criteria for a score of 6 but provide more complete explanation, more thorough development, or a more mature prose style. 6 Adequate Essays earning a score of 6 adequately analyze how Capote uses rhetorical strategies to convey his message to his audience. They develop their analysis with evidence and explanations that are appropriate and sufficient, referring to the passage explicitly or implicitly. The writing may contain lapses in diction or syntax, but generally the prose is clear. 5 Essays earning a score of 5 analyze how Capote uses rhetorical strategies to convey his message to his audience. The evidence or explanations used may be uneven, inconsistent, or limited. The writing may contain lapses in diction or syntax, but it usually conveys the student’s ideas. 4 Inadequate Essays earning a score of 4 inadequately analyze how Capote uses rhetorical strategies to convey his message to his audience. These essays may misunderstand the passage, misrepresent the strategies Capote uses, or may analyze these strategies inaccurately. The evidence or explanations used may be inappropriate, insufficient, or less convincing. The prose generally conveys the student’s ideas but may be less consistent in controlling the elements of effective writing. 3 Essays earning a score of 3 meet the criteria for a score of 4 but demonstrate less success in analyzing Capote’s use of rhetorical strategies to convey his message to his audience. They are less perceptive in their understanding of the passage or Capote’s strategies, or the explanation or examples may be particularly limited or simplistic. The essays may show less maturity in control of writing. 2 Little Success Essays earning a score of 2 demonstrate little success in analyzing how Capote uses rhetorical strategies to convey his message to his audience. These essays may misunderstand the prompt, misread the passage, fail to analyze the strategies Capote uses, or substitute a simpler task by responding to the prompt tangentially with unrelated, inaccurate, or inappropriate explanation. The prose often demonstrates consistent weaknesses in writing, such as grammatical problems, a lack of development or organization, or a lack of control. 1 Essays earning a score of 1 meet the criteria for a score of 2 but are undeveloped, especially simplistic in their explanation, or weak in their control of language. 0 Indicates an on-topic response that receives no credit, such as one that merely repeats the prompt. — Indicates a blank response or one that is completely off topic. Rhetorical Terms Quiz Schedule (2015-2016) Rhetorical Terms for September 2 Language devices 1. synecdoche 2. colloquial 3. litotes 4. metonymy 5. paradox 6. euphemism 7. hyperbole 8. allusion 9. irony 10. apostrophe Rhetorical Terms for September 30 Language devices 1. periphrasis 2. imagery 3. metaphor 4. oxymoron 5. paralipsis 6. personification 7. simile 8. symbol 9. alliteration 10. assonance Rhetorical Terms for September 9 Argument 1. ethos 2. damning with faint praise 3. deductive reasoning 4. false analogy 5. inductive reasoning 6. logos 7. pathos 8. syllogism 9. argument ad hominem 10. non sequitur fallacy Rhetorical Terms for October 7 Syntax devices 1. anadiplosis 2. antanaclasis 3. antithesis 4. chiasmus 5. ellipsis 6. epistrophe 7. epanalepsis 8. inverted syntax 9. rhetorical question 10. polyptoton Rhetorical Terms for September 16 Argument 1. either/or fallacy 2. sweeping generalization 3. post hoc, ergo prompter hoc 4. argument ad populum 5. slippery slope fallacy 6. begging the question 7. circular reasoning 8. straw man fallacy 9. hasty generalization 10. equivocation fallacy Rhetorical Terms for October 14 Writing Modes 1. anecdote 2. cause and effect 3. chronological ordering 4. classification 5. expository 6. order of importance 7. parable 8. parody 9. persuasion 10. spatial ordering Rhetorical Terms for September 23 Syntax devices 1. polysyndeton 2. anaphora 3. loose sentence (cumulative) 4. periodic sentence 5. zeugma 6. tricolon 7. apposition 8. parallel structure 9. asyndeton 10. syllepsis Rhetorical Terms for October 21 Miscellaneous 1. rhetoric 2. satire 3. point of view 4. allegory 5. tone 6. tautology 7. cacophony 8. epithet 9. expletive 10. anesis Additional sources for definitions and examples http://www.americanrhetoric.com/rhetoricaldevicesinsound.htm http://www.uky.edu/AS/Classics/rhetoric.html http://rhetoric.byu.edu/ http://andromeda.rutgers.edu/~jlynch/Terms/ http://www.virtualsalt.com/litterms.htm http://www.logicalfallacies.info/ http://grammar.about.com/od/rhetorictoolkit/Tool_Kit_for_Rhetorical_Analysis.htm