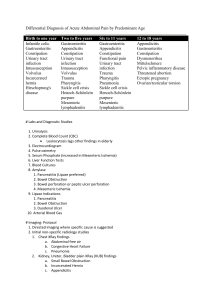

The 'acute abdomen'

advertisement

PEDIATRIC ACUTE ABDOMEN The 'acute abdomen' is a clinical condition characterized by severe abdominal pain, requiring the clinician to make an urgent therapeutic decision. This may be challenging, because the differential diagnosis of an acute abdomen includes a wide spectrum of disorders, ranging from life-threatening diseases to benign self-limiting conditions. Sonography enable an accurate and rapid triage of patients with an acute abdomen. INTUSSUSCEPTION • most common cause of intestinal obstruction between 3 mo and 6 yr of age • 60% percent of patients are younger than 1 yr • 80% of the cases occur before 24 mo • rare in neonates • incidence 1-4/1,000 live births • male:female ratio is 4:1 If intussusception occurs outside the recognized age range, i.e. below 6 months and over 6 years of age, then lead points should be looked for. In the very young infant a Meckel diverticulum may intussuscept, and in the older child, lymphoma infiltrating the bowel wall is the commonest cause. There is an increased incidence of intussusception in children post-surgery with Peutz–Jaeger syndrome or with cystic fibrosis. • cause of most intussusceptions is unknown • seasonal incidence has peaks in spring and autumn • correlation with adenovirus infections has been noted • postulated that swollen Peyer’s patches in the ileum may stimulate intestinal peristalsis in an attempt to extrude the mass, thus causing an intussusception PATHOPYSIOLOGY • Intussusceptions are most often ileocolic and ileoileocolic, less commonly cecocolic, and rarely exclusively ileal • Very rarely, the appendix forms the apex of an intussusception • The upper portion of bowel, the intussusceptum, invaginates into the lower, the intussuscipiens, dragging its mesentery along with it into the enveloping loop. • Constriction of the mesentery obstructs venous return; engorgement of the intussusceptum follows, with edema, and bleeding from the mucosa leads to a bloody stool, sometimes containing mucus • The apex of the intussusception may extend into the transverse, descending, or sigmoid colon--even to and through the anus in neglected cases. This presentation must be distinguished from rectal prolapse • Most intussusceptions do not strangulate the bowel within the first 24 hr but may later eventuate in intestinal gangrene and shock CLINICAL PRESENTATION • “sudden onset, in a previously well child, of severe paroxysmal colicky pain that recurs at frequent intervals and is accompanied by straining efforts with legs and knees flexed and loud cries” • Vomiting in most cases and is usually more frequent early • In the later phase, the vomitus becomes bile stained • Stools of normal appearance may occur during the first few hours of symptoms • then fecal excretions are small or more often do not occur, and little or no flatus is passed CLINICAL PRESENTATION • palpation usually reveals a slightly tender sausage-shaped mass often in the right upper quadrant • about 30% of patients do not have a palpable mass • presence of bloody mucus on the finger after DRE supports the diagnosis • abdominal distention and tenderness develop as intestinal obstruction becomes more acute RADIOGRAPHIC SIGNS OF INTUSSUSCEPTION target sign (may just resemble a solid mass) “pseudokidney” sign because it may have the shape of an oval mass in the RUQ crescent sign absent liver edge sign (also called absence of the subhepatic angle) bowel obstruction KEEP IN MIND… PLAIN ABDOMINAL FILMS CANNOT BE USED TO RULE OUT INTUSSUSCEPTION • Us appearance: • target, hamburger or doughnut appearance in cross section and as a pseudo-kidney in longitudinal section. • Doppler examination should be used to evaluate the vascularity of the intussusceptum, as a poor vascularity may be associated with infarction of the bowel . • In addition, the presence of free fluid trapped between the colon and intussusceptum has been shown in several studies to be associated with a significantly lower success rate of reduction and with ischemia of the bowel. • The presence of lymph nodes in the intussusceptum also reportedly reduces the success rate. • Ultrasonography has a false-negative rate approaching zero and is a reliable screening tool for children at low risk for intussusception 5-9. • Children with classic findings of intussusception, however, need to be investigated with contrast enema, which is both diagnostic (the gold standard in the diagnosis of intussusception) and therapeutic. • Air/contrast enema • diagnostic and therapeutic shows a filling defect in the head of contrast where its advance is obstructed by the intussusceptum • “contrast material between the intussusceptum and the intussuscipiens is responsible for the coil-spring appearance” • The treatment of intussusception is to push the intussusceptum back, usually using air under pressure via a rectal catheter • Reduction of the intussusception is generally performed in the prone position, as it is much easier to maintain a good seal of the tube in the rectum. • Ultrasound can be used to monitor pneumatic and hydrostatic reduction and has the advantage of not using radiation. • In patients with prolonged intussusception with signs of shock, peritoneal irritation, intestinal perforation, or pneumatosis intestinalis, hydrostatic reduction should not be attempted • success rate of hydrostatic reduction under fluoroscopic or ultrasonic guidance is approximately 50% if symptoms are present longer than 48 hr • and 75-80% if reduction is done within the first 48 hr • Bowel perforations occur in 0.5-2.5% of attempted barium reductions. The perforation rate with air reduction ranges from 0.1-0.2% Small bowel intussusceptions can be found incidentally in asymptomatic children and in symptomatic pediatric patients like in this case. There is a difference between the small bowel intussusception and the ileocolic intussusception. The ileocolic intussusception nearly always needs hydrostatic or even surgical treatment . The small bowel intussusception in many cases is a self limiting disease. It is important to look for signs that help differentiating the self limiting small bowel intussusceptions from the ones that need surgical treatment. Transient small bowel intussusceptions resolve during the examination or are resolved during a short term follow up examination. Signs to look for in a small bowL intussusception: Length of the intussusception Wall thickness Vascularity of the bowel wall Identifiable lead point Signs of obstruction Signs of peritonitis • Signs found in intussusceptions that need surgical treatment are: Longer length of the intussusception (usually more than 3,5 cm.) Bowel wall thickening Identifiable lead point Small bowel dilatation Free peritoneal fluid Signs of peritonitis • Signs found in intussusceptions that can be followed up are : Shorter length No bowel wall thickening Normal vascularity No signs of obstruction or peritonitis Fluoroscopy - contrast enema A contrast enema remains the gold standard, demonstrating the intussusception as an occluding mass prolapsing into the lumen, giving the "coiled spring” appearance (Barium in lumen of the intussusceptum and in the intraluminal space) The main contra-indication for an enema is a perforation • CT • CT has become the modality of choice for assessment of acute abdomen in adults, and thus most frequently images intussusception. • In addition short length transient intussusception is a frequent incidental finding. • Best know is the so-called bowel-within-bowel configuration, in which the layers of the bowel are duplicated forming concentric rings (CT equivalent of the ultrasonographic target sign) when imaged at right angles to lumen, and a soft tissue sausage when imaged longitudinally 13. • Differential diagnosis • On imaging the appearances on ultrasound and CT are characteristic. The main differential is that of transient intussusception, which is an incidental finding requiring no treatment or follow-up APPANDICITIS • The normal appendix is a small tubular structure measuring no more than 7 mm in diameter and is easily compressible. It may contain air or fecal material as seen in the proximal bowel. • There should be no fatty echogenic mesentery around the appendix. • The normal appendix can be differentiated from small bowel by the absence of peristalsis, and it does not change its appearance over time. • It should be distinguishable from ascending colon by its size. • In children it is easier to visualize the normal appendix undergoing graded compression than in adults because the transducer is smaller and hence closer to the region of interest. Normal appendix : Longitudinal (A) sonogram depicts a blind-ending tubular structure (arrowheads) with 'gut-signature', with a maximum outer diameter of 6 mm, with noninflamed surrounding fat. On an axial view (B) the appendix can be compressed crossing the iliac vessels. Normal appendix: CT shows an aircontaining non-distended appendix (arrowheads), with homogeneous lowdensity periappendiceal fat. • Appendicitis • Appendicitis is one of the common pediatric emergencies, • occurring primarily in late childhood. While the clinical diagnosis may be straightforward in some cases, there are many other causes of an acute abdomen. • Ultrasound is an excellent technique to aid diagnostic accuracy in the acute abdomen both to visualize the inflamed appendix and to exclude other conditions that may mimic appendicitis. • Typically in acute appendicitis the child will present clinically with initial periumbilical pain which moves to the right iliac fossa and with exquisite tenderness over the inflamed appendix. • Then using a technique of what is called ‘graded compression’, start scanning over the right iliac fossa at the point of maximum tenderness (generally the site of the inflamed appendix). • By gently and progressively compressing over the area, the surrounding bowel is displaced and th compressibility of the appendix assessed. • If the appendix is retrocecal, a lateral and posterior approach should be used. • What are the radiological findings of appendicitis in abdomen ultrasound? • The most sensitive sign of appendicitis from ultrasound is a non compressible appendix with a diameter of 7mm or greater. • Other findings may include: • • • • appendicolith thickened appendiceal wall abscess fluid around the appendix APPENDICITIS The inflamed appendix is non-compressible/ The diameter of the appendixis over 6 mm and may even be up to 20 mm The surrounding mesentery and omentum become highly echogenic In 30% of cases a fecolith may be identified If the appendix is perforated there may be an associated pelvic mass which, in a female,usually accumulates in the pouch of Douglas On Doppler examination there is a marked increase in vascularity Enlarged lymph nodes may be noted within the abdomen An ileus may be present showing nonperistaltic fluid-filled loops of bowel There may be a para-appendiceal abscess and collection of pus Inflamed appendix at sonography. Longitudinal (A) and transverse (B) crosssection show a distended noncompressible appendix, surrounded bij hyperechoic inflamed fat (arrowheads). Appendicitis with an inflamed tip but normal proximal part Appendicitis with a 2,2 cm large appendicolith / fecolith Appendicitis in a 3 year old boy with a thickened appendix hyperechoic fat and hypervascularity Appendicitis in a 9 year old boy with a thickened vascularized appendix and hyperechoic mesoappendix • Appendix abscess. He was treated conservatively and recovered. • The main differential diagnoses to look for and exclude in children are: • renal abnormalities, ovarian cysts, intussusception, inflammatory bowel disease and mesenteric lymphadenitis • There are no specific signs of appendicitis in plain films but you may see: • • • • ileus appendicoliths sentinel loop (dilated adjacent ileum) evidence for complications like perforation or appendiceal abscess • widening and blurring of peritoneal fat line • right lower quadrant haze due to fluid, edema and mass • mass indenting the cecum Plain film showing appendicolith. Arrow points to ileus. Appendicolith may be seen without clinical signs of appendicitis White arrow points to appendicolith. D is the diameter of the appendix measuring more than 7 mm. Arrowheads point to distended appendix. Black arrows point to posterior shadowing. • What are the radiological findings of appendicitis in abdomen CT? • Ileus: Dilated loops of bowel Appendix > 6mm in diameter An appendicolith Failure of the appendix to fill with oral contrast medium Enhancement of its wall with intravenous contrast medium Periappendiceal inflammation/inflammatory infiltration of fat Free fluid in cul de sac Abscess • Inflammatory (phlegmon) mass • Air pockets • Contrast enhancement • Extraluminal gas from perforation • Pericecal lymphadenopathy • Cecal wall thickening • • • • • • • Inflamed appendix at CT. The appendix (arrows) is fluid-filled and distended with periappendiceal fat-stranding. Arrows point to the inflammatory mass in the right lower quadrant with an air pocket, indicating an abscess. Mass demonstrates contrast enhancement. • What is the sensitivity and specificity of each imaging procedure in diagnosing appendicitis? • CT: • Spiral CT has a sensitivity of 90-100%, a specificity of 91-99%, a positive predictive value of 95-97%, and an accuracy of 94100%. • Ultrasound: • The limitation to ultrasound is that the appendix is often unseen due to associated bowel gas. • When carefully performed it has a sensitivity of 75-90 percent, a specificity of 86-100 percent, and a positive predictive value of 89- 93 percent for the diagnosis of appendicitis. • It is operator dependent • What are the potential complications of acute appendicitis? • Perforation (most serious) • Pyelophlebitis with thrombosis of the portal vein • Liver abscess • Mesenteric lymphadenitis. • Mesenteric lymphadenitis is a common mimicker of appendicitis. It is the second most common cause of right lower quadrant pain after appendicitis. It is defined as a benign self-limiting inflammation of rightsided mesenteric lymph nodes without an identifiable underlying inflammatory process, occurring more often in children than in adults.. This diagnosis can only be made confidently when a normal appendix is found, because adenopathy also frequently occurs with appendicitis. Key finding: Lymphadenopathy with a normal appendix and normal mesenteric fat. Normal appendix (green arrow) and enlarged mesenteric lymphnodes (yellow arrows). • Bacterial ileocecitis • Infectious enterocolitis may cause mild symptoms resembling a common viral gastroenteritis, but it may also clinically present with features indistinguishable from appendicitis especially in bacterial ileocecitis, caused by Yersinia, Campylobacter, or Salmonella. Key finding: ileocecal wall thickening without inflamed fat, adenopathy, normal appendix US typically shows submucosal wall thickening (arrowheads) of the terminal ileum and cecum without inflammation of the surrounding fat MALROTATION MALROTATION • Intestinal maltoration • is a congenital anatomical anomaly which results from an abnormal rotation of the gut as it returns to the abdominal cavity during embryogenesis. Although some individuals live their entire life with malrotated bowel without symptoms, the abnormality does predispose to midgut volvulus and internal hernias, with the potential for life threatening complications • Midgut malrotation has been estimated to occur in approximately one in 500 live births . However, it is difficult to ascertain the true incidence • It is also frequently (~ 50%) associated with other abdominal anomalies, some of which are causative and others merely associated:duodenal atresia / stenosis / web /congenital diaphragmatic herniation /gastroschisis /omphalocele heterotaxy : 70% of individuals will have a malrotation /choanal atresia • Clinical presentation • correlates to the age of presentation 5. • In the infant the most common presentation is with / midgut volvulus. • In the older child or even adult presentation is more frequently intermittent with episodes of spontaneously resolving duodenal obstruction. This is thought to be due to kinking of the duodenum by Ladd bands rather than a volvulus 5. Internal hernias are also encountered. • In some individuals, presentation is very non-specific with episodes of abdominal pain, weight loss, melaena, or even chronic pancreatitis • Pathology • During normal embryogenesis the bowel herniates into the base of the umbilical cord and rapidly elongates. As it returns to the abdominal cavity it undergoes complex ~270 degree counter clockwise rotation resulting in the duodeno-jejunal (DJ) flexure normally located to the left of the midline, at the level of L1 verterbal body and the terminal ileum located in the right iliac fossa. This results in a broad mesentery running obliquely down from the DJ flexure to the caecum, and prevents rotation around the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) 1-6. • In malrotation this does not occur and as a result the mesentery has a short root, which allows it to act as a pedicle (through which the SMA and SMV pass) around which volvulus can occur. • Plain film • Abdominal radiographs, in the absence of midgut volvulus, are neither specific nor sensitive 2. • They may show: right sided jejunal markings absence of stool filled colon in right lower quadrant 29-year-old woman with chronic intermittent abdominal pain. Supine frontal abdominal radiograph shows small bowel with jejunal markings on right (arrowheads) and colon predominately on left. Note absence of colon in right lower quadrant (arrow). • Ultrasound • May show and inversion in the SMA /SMV relationship with the SMA on the right and the SMV on the left. Transverse sonogram obtained through upper abdomen in 11-year-old girl with malrotation shows vertical or slightly inverted orientation between superior mesenteric artery (arrowhead) and superior mesenteric vein (v • CT • may again show abnormal SMA (smaller and more circular) / SMV relationshipvein (SMV) is a useful indicator of malrotation . • In most patients with quiescent malrotation, the SMA and SMV will assume a vertical relationship or show left—right inversion . • large bowel predominantly on left and small bowel predominantly on the right • inspection of the pancreas in malrotation will reveal underdevelopment or absence of the uncinate process . 32-year-old man with left flank pain. Axial contrast-enhanced CT s shows inverted relationship between superior mesenteric artery (arrowhead) and superior mesenteric vein (v). Note absence of pancreatic uncinate process. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan obtained through mid abdomen shows characteristic appearance of small bowel on right and colon on left —22-year-old man with episodic colicky abdominal pain. Axial contrastenhanced CT scan shows vertical orientation of superior mesenteric artery (arrowhead) and superior mesenteric vein (v). show bowel dilatation and mucosal hyperattenuation, findings indicative of global small-bowel ischemia. There is a twist at the root of the small-bowel mesentery, and an abnormal relationship between the superior mesenteric artery (long arrow) and the superior mesenteric vein (short arrow) is seen. Appendicitis in patients with malrotation. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scans in 56-year-old woman with left lower quadrant abdominal pain, vomiting, and leukocytosis show abnormal dilated appendix with marked periappendiceal stranding extending from left-sided cecum. Note also superior mesenteric artery—superior mesenteric vein inversion Appendicitis in patients with malrotation. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan in woman with left-sided abdominal pain and clinical diagnosis of diverticulitis shows enlarged appendix (A) with periappendiceal inflammation on left. Note terminal ileum (asterisks) crossing to left-sided cecum. • Fluoroscopy • paediatric upper gastrointestinal contrast study is the examination of choice when the diagnosis is suspected. The key findings of malrotation are: • abnormal duodeno-jejunal (DJ) junction location • duodenum fails to cross the midline • DJ flexure lies inferior to the duodenal bulb • Contrast enema has historically also been used, the theory being that in malrotation the large bowel will also be malrotated. Unfortunately in 20 - 30% of cases with malrotation the caecum is normally located. The converse is also true, with position of the caecum in normal individuals being variable 4. • Malrotation Presenting with Acute Symptoms • Midgut volvulus is a complication of malrotation in which clockwise twisting of the bowel around the SMA axis occurs because of the narrowed mesenteric attachment . • The clinical diagnosis of midgut volvulus in adolescents and adults is difficult because the presentation is usually nonspecific and malrotation is rarely considered. Recurrent episodes of colicky abdominal pain with vomiting over a period of months or years are typical and may eventually lead to imaging . • Diarrhea and malabsorption from chronic venous and lymphatic obstruction may also occur . • Findings • on abdominal radiographs in midgut volvulus are usually abnormal but non-specific . • Upper gastrointestinal examination (the study of choice in neonates) shows the typical corkscrew appearance of the proximal small bowel. • However, in older patients with acute symptoms, CT is generally performed instead of a barium examination. . The CT whirl or whirlpool sign describes the swirling appearance of bowel and mesentery twisted around the SMA axis. A similar appearance can be seen on sonography. • Additional CT findings include duodenal obstruction, congestion of the mesenteric vasculature, and evidence of underlying malrotation . • The presence of intestinal ischemia or necrosis is an ominous sign 6-day-old girl with malrotation and midgut volvulus Midgut volvulus in an infant Lateral upper GI image obtained in a different patient also shows the classic corkscrew-like • Barium study showing the typical twisted ribbon appearance of the proximal small bowel in malrotation and volvulus. 29-year-old man with acute abdominal pain and vomiting His history was significant for similar prior episodes without diagnosis. Axial contrastenhanced CT scans show characteristic whirllike appearance of bowel and mesentery wrapping around superior mesenteric artery (arrowheads,). Note dilated duodenum /engorged mesenteric vessels 12-year-old girl with acute abdominal pain from malrotation with midgut volvulus. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scans show characteristic clockwise twisting of bowel, mesentery, and superior mesenteric vein (arrowheads) around axis of superior mesenteric artery. • Internal hernia • caused by abnormal peritoneal bands is an underrecognized complication of malrotation after childhood . • This condition may also be life-threatening because of the risk of bowel obstruction and strangulation. • CT findings of malrotation and small-bowel obstruction (without volvulus) may be seen in patients having this complication . • Evidence of ischemic bowel again portends a poor prognosis . • Some patients may present with a combination of midgut volvulus and internal hernia . 23-year-old man with acute abdominal pain from malrotation with internal hernia and partial midgut volvulus. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scans show dilated duodenum (D, A), small whirl sign involving more distal superior mesenteric artery (arrowheads, B), and malpositioning of bowel. Localized cluster of unopacified bowel or fluid is present inferiorly (arrows, C). Internal hernia with encapsulated appearance was found at surgery MESENTERIC LYMPHADENOPATHY • Mesenteric lymphadenopathy is a common finding when examining the abdomen in children and is generally reactive. • It can be found in the folds of the small bowel mesentery around the superior mesenteric artery and vein and in the arteries supplying the jejunum and ileum. • They are normally less than 5 mm in diameter . ACUTE PANCREATITIS Normal dimensions of the pancreas as a function of age in children • Maximal anteroposterior diametera (cm) 0–6yr:head 1.6cm (1.0–1.9)/ body 0.7cm (0.41.0) /tail 1.2cm (0.8–1.6) 7–12yr :head1.9cm (1.7–2.0) /&body0.9cm (0.6–1.0) & tail 1.4 (1.3–1.6) 13–18yr: head2.0cm (1.8–2.2) /&body1.0cm(0.7-1.2) tail1.6cm(1.3-1.8) The commonest cause of acute pancreatitis in pediatrics is blunt abdominal trauma, most commonlyfrom road traffic accidents or non-accidental injury. ther causes include infection such as mumps, drug toxicity and biliary and pancreatic anomalies .Biliary lithiasis is a rare cause in children. Acute pancreatitis is uncommon in childhood,and when it does occur no obvious precipitating cause can be found. Trauma as a result of child abuse is one of the commonest causes, whereas hereditary causes are most common for chronic pancreatitis. . when pancreatitis is prolonged, pleural effusions and pancreatic pseudocysts may occur. The diagnosis is confirmed by markedly raised amylase levels. • Pediatric Pancreatitis cause: • • • • • • • Inflammation / Infection –Trauma –Cholelithiasis –Familial –Congenital –Pancreas Divisum –Medications –Viral (mumps, coxsackie, CMV, EBV) • • • • • • Pancreatitis: Imaging Findings Ultrasound “normal” Focal / diffuse enlargement Peripancreatic fluid +/-gallstones, Biliary ducts Vascular thrombosis • Pancreatitis Imaging Findings CT: • • • • • Focal / diffuse enlargement Peripancreatic fluid / stranding Necrosis (↓density, enhancement) Vascular thombosis Pseudocysts o In the diagnosis and staging of acute pancreatitis and its complications CT is the imaging modality of choice. o Ultrasound is important in determining whether gallstones are the cause of the acute pancreatitis (i.e. biliary pancreatitis). o ERCP with sphincterotomy and stone extraction should only be used if a patient has biliary pancreatitis and signs of biliary obstruction. o MRI is as sensitive as CT, but not as practical or accessible. • The diagnosis is usually made on clinical and laboratory findings. • There is no additional value of an early CT (within 72 hours) in patients with acute pancreatitis. • An early CT may be misleading concerning the severity of the pancreatitis, since it can underestimate the presence and amount of necrosis. • Early CT is only recommended when the diagnosis is uncertain, or in case of suspected early complications such as perforation or ischemia. • In mild pancreatitis the gland may appear normal but usually there is evidence of edema with an enlarged gland which appears hypoechoic. • The ultrasound findings are diverse and may be diffuse or focal gland enlargement. The borders of the gland may be poorly defined and there may be dilation of the duct. • Severe acute pancreatitis may be complicated by complete gland necrosis, which is best demonstrated by CT. This may become infected in a significant proportion, and the presence of air either from a fistula or the infection means that this needs to be drained. • Fluid collections arise in or adjacent to the pancreas in acute pancreatitis, and the majority will resolve spontaneously. • Some may persist, but others may develop into pseudocysts. • Pancreatic pseudocysts have fibrous capsules. Pseudocysts evolve from an acute collection and may take several weeks to develop. • CT Severity Index • It is critical to identify patients who are at high risk for severe disease, since they require close monitoring and possible intervention. • Early staging is based on the presence and degree of systemic organ failure (cardiovascular, pulmonary, renal) and on the presence and extend of pancreatic necrosis. • Balthazar et al constructed a CT severity index (CTSI) for acute pancreatitis that combines the grade of pancreatitis (A-E) with the extent of pancreatic necrosis. • Mild pancreatitis • Patients with pancreatitis but no collections or necrosis (i.e. Balthazar grade A-C) have a mild pancreatitis. This is also called 'edematous or interstitial pancreatitis' (no pancreatic necrosis). • It is a self-limiting disease with an uneventfull recovery occurring in 80% of patients with acute pancreatitis. • There is an intermediate form of pancreatitis without pancreatic necrosis with an intermediate clinical course. • This is called extrapancreatic necrosis (EXPN) . Sometimes the term exudative pancreatitis is used. • These patients have Balthazar grade D or E. • These patients have a relatively mild course because there is no pancreatic necrosis, but there is higher morbidity than in interstitial pancreatitis, because they have peripancreatic collections, that can become infected • Severe pancreatitis or necrotizing pancreatitis • Severe pancreatitis, also called 'necrotizing pancreatitis' occurs in 20% of patients. It is characterized by a protacted clinical course, a high incidence of local complications and a high mortality rate. Interstitial pancreatitis On the left there is normal enhancement of the entire pancreatic gland with only mild surrounding fatty infiltration. There are no fluid collections or necrosis (Balthazar grade C, CTSI: 2). • Exudative Pancreatitis • In exudative pancreatitis, or better called EXPN, there is normal enhancement of the entire pancreas associated with extensive peripancreatic collections. These are often heterogeneous in appearance and may be progressive. • EXPN consists of necrosis of peripancreatic fat, extravasated pancreatic fluid and inflammatory and hemorrhagic components. When peripancreatic collections persist or increase, it is usually due to the presence of fat necrosis (i.e. EXPN). Since fat does not enhance on CT, we cannot diagnose fat necrosis. In the case on the left on day 18 there is expansion of the peripancreatic collections. There are two or more collections, but no pancreatic necrosis. (Balthazar grade E, CTSI: 4) • Central gland necrosis • Central gland necrosis is a subtype of necrotizing pancreatitis. It represents necrosis between the pancreatic head and tail and is nearly always associated with disruption of the pancreatic duct. This leads to persistent collections as the viable pancreatic tail continues to secrete pancreatic juices. These collections react poorly to endoscopic or percutaneous drainage. Definitive treatment often requires distal pancreatectomy PERIPANCREATIC COLLECTIONS • Intraabdominal fluid collections and collections of necrotic tissue are common in acute pancreatitis. • These collections develop early in the course of acute pancreatitis. In the early stage such a collection does not have a wall or capsule. Preferred locations are the omental bursa and the retroperitoneal space (anterior and posterior pararenal space). • These collections are the result of the release of activated pancreatic enzymes (namely lipase, trypsin and amylase) which also causes necrosis of the surrounding tissues. This explains why a lot of these collections contain solid debris. • 50% of these collections show spontaneous regression The other 50% either remain stable or increase and undergo organization and demarcation with liquefaction. They may remain sterile or develop infection There is a fluid collection in the omental bursa, adjacent to the stomach. Notice the normal enhancement of the pancreatic head and tail, but the lack of enhancement of the majority of the pancreatic body. Spontaneous regression of peripancreatic collection Pancreas surrounded by fat stranding due to exsudative pancreatitis.