Chhaupadi: A Socio-cultural Practice during Menstruation in Far

advertisement

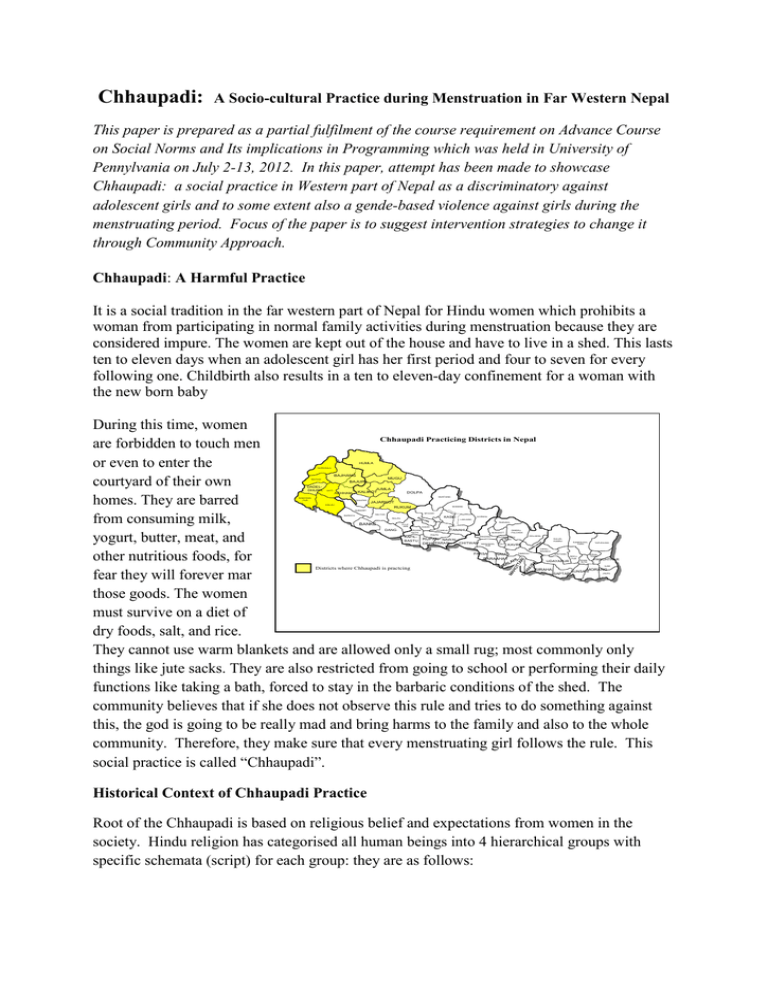

Chhaupadi: A Socio-cultural Practice during Menstruation in Far Western Nepal This paper is prepared as a partial fulfilment of the course requirement on Advance Course on Social Norms and Its implications in Programming which was held in University of Pennylvania on July 2-13, 2012. In this paper, attempt has been made to showcase Chhaupadi: a social practice in Western part of Nepal as a discriminatory against adolescent girls and to some extent also a gende-based violence against girls during the menstruating period. Focus of the paper is to suggest intervention strategies to change it through Community Approach. Chhaupadi: A Harmful Practice It is a social tradition in the far western part of Nepal for Hindu women which prohibits a woman from participating in normal family activities during menstruation because they are considered impure. The women are kept out of the house and have to live in a shed. This lasts ten to eleven days when an adolescent girl has her first period and four to seven for every following one. Childbirth also results in a ten to eleven-day confinement for a woman with the new born baby During this time, women Chhaupadi Practicing Districts in Nepal are forbidden to touch men or even to enter the courtyard of their own homes. They are barred from consuming milk, yogurt, butter, meat, and other nutritious foods, for fear they will forever mar those goods. The women must survive on a diet of dry foods, salt, and rice. They cannot use warm blankets and are allowed only a small rug; most commonly only things like jute sacks. They are also restricted from going to school or performing their daily functions like taking a bath, forced to stay in the barbaric conditions of the shed. The community believes that if she does not observe this rule and tries to do something against this, the god is going to be really mad and bring harms to the family and also to the whole community. Therefore, they make sure that every menstruating girl follows the rule. This social practice is called “Chhaupadi”. HUMLA DARCHULA BAJHANG MUGU BAITADI BAJURA DADELDHURA JUMLA KALIKOT DOTI ACHHAM DOLPA MUSTANG KANCHANPUR DAILEKH KAILALI JAJARKOT MANANG RUKUM SURKHET MYAGDI SALYAN BARDIYA GORKHA KASKI ROLPA LAMJUNG PARBAT BANKE PYUTHAN DANG RASUWA GULMI ARGHAK HACHI KAPILBASTU SYANGJA TANAHU SINDHUPALCHOK NUWAKOT PALPA DHADING RUPAN- NAWAL CHITWAN DEHI PARASI MAKAWANPUR DOLAKHA KATHMMANDU BHAK LALIT SULUKHUMBU SANKHUWASABA KAVRE TAPLEJUNG OKHALDHUNGA PARSA RAUTBARAAHAT SINDHULI KHOTANG UDAYAPUR Districts where Chhaupadi is practcing TERHATHUM BHOJPUR DHANKUTA PANCHTHAR ILAM SIRAHA MORANG SAPTARI SUNSARI JHAPA Historical Context of Chhaupadi Practice Root of the Chhaupadi is based on religious belief and expectations from women in the society. Hindu religion has categorised all human beings into 4 hierarchical groups with specific schemata (script) for each group: they are as follows: 1. Brahmin: People who are wise and learned by profession. In Sanskrit, they are called “Pandit” who imparts learning to all and are the teachers and guides. 2. Chhetri: People who are the warrior class who are in front line in national defence profession; 3. Vaishya: People who are skilled professionals, businessmen and artists; and 4. Shudra: People whose profession is cleaning public places, butchering and any “undesirable” activities to be performed by the common people. This group is called “untouchables” and in Nepal also called as Dalits. The fourth group of people live in their own community and are not allowed to enter the house of the above 3 high class groups. The high class group does not accept any food from this group. Even in tea shops they are expected to clean their own cups after drinking the tea. This practice, they believe is from Vedic period and it is still practiced in Far Western Nepal. According to the Hindu religion, female falls into the fourth category of people 4 days a month when they are menstruating. This religious belief is the root cause for practicing this social norm. Impact of Chhaupadi on Girls’ Everyday Lives Educational Implications: As mentioned above, girls who are menstruating are not allowed to mingle with others, not allowed to go to temple and touch anything that has to do with the god. First of all, Hindus believe that a school is a temple where Goddess Sarswoti1 resides. There is a normative expectation from the school that the community thinks menstruating girls should not enter the temple. This restricts a menstruating girl going to school during these days. Even during the examination time, they are not allowed to go to school. In any case, a girl ventures to go and if the school management finds out, she is in trouble and thrown out of the classroom. There has been some media reporting on this issue when a girl who was attending a final examination, she had been thrown out of the examination hall when the head teacher found out about it. Reflection of this normative expectation has been a “wrecking ball” for a good number of adolescent girls who are not vey inspired to go to school. When they miss out 4-11 days a month in the school, there has been some consequences on the homework to be done and other negative reinforcement from teachers and school management. Nationally, 44.2% of adolescent girls currently aged 15-19 dropped out from secondary school. 21.3% have never been in school. Physical Safety and Condition of Living Implications: The geographical area in Far Western Nepal where the Chhaupadi is practiced is very widely known for attacks by animals and reptiles, such as leopard and also snakes. There have been 1 Sarswoti is a goddess of learning. many cases where the girls were stung by snake and dragged by leopard while they are in Chhaupadi. One of the twitters has written that: Chhaupadi ritual and culture can be a serious ‘matter of life and death’ for many girls and women in Nepal, especially those living in the western districts. Winter months are exceptionally critical for girls and women isolated in menstrual sheds. “A person with severe hypothermia may be unconscious and may not seem to have a pulse or to be breathing”, explains the U.S. Center for Disease Control report. “In this case, handle the victim gently, and get emergency assistance immediately”. Two weeks after the 2010 death of Belu Damai, another chhaupadi death occurred in Nepal’s Achham district. The January 17 death of thirty-five year old Jhupridevi Hudke happened when low temperatures hit the region. Hudke died inside a hut in the village of Payal after staying in a menstrual shed for five days. Her eight-month-old son, who was with her at the time, was found unconscious. This is one of the staunch socio-cultural practices practiced in Nepal and also considered as gender based violence against women and adolescent girls. When this practice is analyzed in terms of the theoretical framework, the following things are very obvious: Factual Belief: If a mensuarating girl disobeys the rule, god will be angry and her family will face a bad luck; which may range from falling sick to some natural disastersfire in the community, sudden death of a cattle2 and even a family member, cows/buffalos suddenly stop giving milk. If she touches a tree it will never again bear fruit. All of these are bad luck for any rural agro-based economy family. Moreover, if there is any disaster in the community, the blame goes to the girl who just had observed the Chhaupadi, and will be accused of not observing with full purity. If she reads a book, Saraswati, the goddess of education, will become angry. If she touches a man, he will be ill. One article written by Nirmala Kandel and et al states that “She will become sexually dangerous and harm would come to any partners' genitals and person cannot have sex and could be harmful to family members, village etc if the seclusion is broken. If these women were unable to maintain these traditions, their community would be shattered and would no longer survive”. Conditional Preference: No family wants to get disgrace from the community. It is not only the issue of a girl not observing, but the whole family gets deprecated. The family does not get invitation in community events. With these reasons, parental as well as girls’ preference will follow the rules of Chhaupadi whenever other members of the community to do and expect them to do so to simply follow the rule and observe the Chhaupadi. Empirical Expectation: Community members generally expect that every girl in that community goes to live in Chhaupadi for four to seven days during their mensuration period. She does not observe any religious activities, does not touch 2 Cattle is a very important asset for any family in rural Nepal. There is even a saying that “if a wife dies, you can marry again, but if a cattle dies, it is a financial loss” anything that has to do with the religious rituals or god. She does not go to school during this period. Normative Expectation: Every parent/in-laws believes that the community expects any menstruating girl should observe this rule strictly, failed to adhere, will result in family bad luck. According to Mockus, any behavior and any decision is influenced by three regulatory systems, a legal system, a moral system and the social system. The legal system influences actions by respect for law and fear of punishment, the moral through moral esteem and guilty, and the social through acceptance and shame has to be analyzed in 3 different systems of norms. Trying to analyze the Chhaupadi in Mockus’s framework, it can be seen as follows: Associated types of Emotion Positive Negative Legal Formal Norm (Respect Law) Moral Norm (Conscience) Social Norm (Belongingness) Not Applicable at this point. However, there is a recent news in the internet that a case has been filed by the women lawyers in the Supreme Court to ban the Chhaupadi. It is self-gratifying for girls as well as for the family by complying with religious values and personal normative beliefs Acceptance from the society and Image incentive is high Girls and menstruating women go through the Fear of Guilt for not complying with personal normative beliefs. In case of taking risk and not complying the normative expectation, there is always a Fear of Social Disapproval or Rejection Note: Girls and menstruating women lack education on mensuration hygiene, empowerment to increase the self- empowerment. Moreover, older generation (mothers/ mother-in-laws, husbands) need to be brought towards the “common knowledge” on the normalcy of the phenomena of mensuration. It is very obvious among the young people that they do not want to adhere this practice, but they need firm support from the older generation to make them feel guilt free. Normative expectation of the older generation has to be changed along with young people who are already in a “tipping point”. The “script” of the Chhaupadi curse has to be changed to a positive behaviour. Argument on Chhaupadi as a Social Norm Biccheiri in her presentation, defines Social Norm, as “a pattern of behavior such that individuals prefer to conform to it on condition that they believe that (a) most people in their relevant network conform to it (empirical expectation), and (b) that most people in their relevant network believe they ought to conform to it (normative expectation)” If they do not conform it there is a social consequences. She has also very well discussed about the “Belief Traps ”by giving example from a UNICEF study on Violence on Children. In the study it was found that the caregivers do not consider punishment as positive measure to discipline children, still large number of care givers are still practicing punishment to the children. Similar evidence can be found in Chhaupadi practice. From informal discussion with young girls it is very clear that they are against the practice, but they seemed to be still practicing partially due to their belief traps than due to factual beliefs. A women who runs a tea shop in the village, has clearly said in an TV interview that she has stopped observing this practice, as “everything that goes wrong, the blame is on women, anyway. People fall sick, die and these are natural phenomena”. . She also mentions that some customers have stopped coming to her tea shop, just because she is considerate as social “outlaw”, but she does not care and her husband does not care either. According to Biccheiri and Fukui(1999) a trendsetter questions “the standing norm and starts behaving differently to effect a change”(Bicchieri & Mercier, no date). This woman can be viewed as a “trendsetter” and in personal communication with young girls in the community, the writer can confirm that they are in the “belief traps” rather than “pluralistic ignorance”. People talk negatively on this practice very openly but at the end they observe it saying, “this has been the custom and we have to follow to please the god” is the final statement. In this practice, it is very evident that there is conditional preference, empirical expectation and normative expectations. Thus this is a social norm and it is a harmful practice for menstruating girls and women at large extent. There is also an argument that “Procedural Justice” or legal government injunction might influence people’s judgement and their behavior. One example from legal requirement for rural migrant enterpreneurs’ disobedience to the business license in China illustrates that sometimes, it does more harm than good. Similar case on female genital mutilation also has demonstrated that if the law is in one country, families tend to go to bordering county to follow the social norm anyway. Thus, I agree with Biccheiri and Mercier, when they mentioned that “. . . a government diktat would work for conventions, but be more problematic in case of social norms” (p. 5). However, there is definitely a role of legal directives and cannot be undermined, especially where local government and authorities are part of a community. The curse of Chhaupadi is not limited to the menstruating girls and women; it extends to the male partners, too. Thus, the range of its influence also links with male. As there are many factual beliefs linked with male resulting in serious consequences, they are also afraid to take this risk. Eventually, they are also supporting the social practice to this date, regardless of their economic and educational status. Here an example from TOSTAN is very helpful to learn that male members have to be brought in the circle of community that we talk about. Nevertheless, male and female may be together sometimes and sometimes may need different interventions. In South Asia, besides gender issues, communities need to be classified in terms of education, economic status, geographical location, religion and language. However, overall any community needs to be seen in terms “mainstream elites” versus “marginalized” groups who may be women, lower strata ethnic groups or people with differently ability. Social norms to these groups may be different depending on the issues and location of the community. Biccheiri in the article “The Rules We Live By” argues that the definition of social norm needs to be taken as “rational reconstruction of what a social norm is, not a faithful descriptive account of the real beliefs and preferences people have or of the way in which they in fact deliberate.” She further states that “such reconstruction, however, will have to be reliable in that it must be possible to extract meaningful, testable predictions from it” (Biccheiri, 2006). In the same article, she explains two models of reaching a decision to change the personal belief and eventually to reach the community as a whole – 1) traditional rational model and 2) prescritive model. The first model starts with the systematic assessing the situation, gather information, list and evaluate the consequences and then calculate the expected utility of the alternative courses of action. Critical Evaluation of the Work So Far Many people are raising their voices in Nepal to abolish the Chhaupadi practices; some NGOs are also trying to advocate and raise awareness on the issue, however they are not “organized diffusion”. They are more sporadic and have not been able to reach the hardcore marginalized communities. A very few studies have been done on Chhaupadi, so empirical data does not exist, except occasional media reporting when serious accidents happen in Chhaupadi. Recently, a case has been filed in the Supreme Court of Nepal to eliminate these cruelties forever. The Supreme Court has ordered the government to declare the practice as evil and given it one month to begin stamping the practice out. However, Pushpa Bhusal, a leading lawyer, said it was a positive move in removing the traditional discrimination against women . . .but also warned that a change in the law alone would not be enough, people needed to be educated against such a scourge of society. The education ministry is hoping to establish a new annual literacy plan in the region; including three days of health education classes dedicated exclusively to reproductive health and menstruation hygiene. These interventions lack community consultation, deliberations and argumentation, they are rather outsiders imposition by development workers, such as NGOs. In many rural areas development NGOs are labelled as “dollar farming organizations”; thus the trust level is very low, although they are very crucial for any kind of change in the communities. This is especially true in a county, like Nepal where political stability is a problem and the local government is very weak. On the positive side, many network groups exist in the community level to start with – women groups, School Management Committees, Parent Teacher Association, child clubs and youth clubs. These are all community based. However, representation in the network group is still a problem, as there is an elite capture in every network group. When the networking groups are heavily dominated by the high cast groups and other elites, the marginalize groups tend to be either very submissive or not participate at all. Therefore, a special measure needs to be taken for their meaningful participation in the group. Intervention Goal Social norm on menstruating girls changed from discriminatory practice of Chhaupadi to a social norm against harmful aspects of Chhaupadi. In addition, the interventions should be developing common knowledge on menstrual cycle as natural biological phenomena. Proposed Intervention Strategy Proposed major activity in this paper is to deconstruct the existing social norm and to introduce a new norm. For this purpose, Biccheiri and Mercier suggest that the individual or community need the assurance that they will not suffer the negative consequences. According to Biccheiri’s traditional rational model, along with situation analysis, assurance and conscious commitment is very important. She has argued well that deliberations, argument and common knowledge can change the social beliefs (Biccheiri & Mercier, no date). This demands focus on bottom up approach and community will be the central point and will be the main actor while outsiders will be facilitators. Based on this argument, the present intervention strategy will build upon major elements: 1) Deliberation, 2) Argumentations and 3) Common Knowledge within the community by the community and for the community. Recommended intervention strategies are as follows: 1. Identify the team of leaders from the settlements who will be engaged in site visits where the Chhaupadi is not observed anymore. The leaders should be the ones who are not only political leaders but those who are trusted by the community and respect them as role models and they must be from different strata of society; 2. Ensure the participation from marginalized communities, specifically to bring proportionate representation from women, dalit, and people with differently able. 3. Ensure the participation of young girls (19-24 years) in the whole process. 4. Engage them in interaction with those families, who are not practicing it anymore, let them ask questions and engage them in argumentation; 5. Map out the households where the Chhauapadi shed is still there and mark the households which do not have the shed attached. Similar activity has been done with the communities in 2006 to identify the household where the children has not registered in the school. Please see the example of the map in the box: 6. Empower the individuals and community with knowledge on menstrual hygiene; 7. Let the leaders facilitate the process to develop an action plan to come Miss out 4-11 days of school every month 44.2% of adolescent girls currently aged 15-19 dropped out from secondary school. 21.3% have never been in school School Mapping- identifying the children out of school up with a new social norm and to monitor the practice in participatory way. They also will decide on Image Incentive and corrective measures in terms of violation of social norm. 8. Community members signing on the new social norm as a collective behavior and making it public. 9. Establish a “Watch Group” to monitor the community adhered to their new social norms. 10. Terms of Reference will be developed for Watch Group by the larger group; 11. Watch Group will monitor the practice and Image incentive will be provided to those who are adhering the social norms. 12. Watch Group will council the household where the practice is still on. 13. Engage child club members to publicize in their newsletter and encourage their peers to go to school during menstrual period. As a result of these interventions, a new social norm will be introduced which will be as follows: Girls are not secluded into an unsafe shed during their menstruating period and treated normal with regular food and attending school regularly. Those households, where these girls are still secluded and treated differently will be hold accountable as a violation of social norm. This will foster the conditional preference among the community members to abandon the practice on the condition that others do so. Persons will want to achieve the Image incentive and to avoid the counseling activity. The community will provide safe place to live and provide regular food for girls during their menstruating period. Community will be convinced that all members in their community think that they should treat their girls normal during the mensuration period and send them to the school regularly. Conclusion Among other gender based discriminations, Chhaupadi is one of the social practices which violates the CRC (Child Rights Convention) and compels menstruating girls to spend 4-7 nights outside home in an unsafe shed. Conditional preference of the community members is the fear of direct and indirect social sanction if they do not practice the custom. They believe that all the community members think that every girl/woman who is menstruating should follow this to make community healthy and safe, if not god will punish not only to the disobeying girl/woman but also to the whole community. Their empirical expectation is that all menstruating girl observe the rule and do not mingle around with others. This is a strong, chronic and very harmful practice for the girls. At one hand, they are facing the vulnerable situation every month and the other they are also loosing their opportunity to regular school education. Long term psychological effect of this practice is that birth of a female child is a curse. Therefore, a new social norm has to be introduced against the existing practice. However, it may backfire, if an outsider tries to intervene. It has to be from within the same community, new intervention strategies need to develop to introduce a new norm in the society. This is possible when there is open deliberations, argumentations and common knowledge within the community. When a trendsetter is born among the group, inconsistency will be obvious. This will facilitate more argumentations and deliberations. Gradually, inconsistency in factual belief will inspire the early adopters to follow the trendsetter, who will pull early majority and eventually the other late majority and laggards. References Biccheiri, Christina. 2006. “The Rules We Live By” in The Grammar of Society: The nature and Dynamics of Social Norms. Cmbridge University Press. Biccheiri, Christina. 2006. “Habits of the mind” in The Grammar of Society: The nature and Dynamics of Social Norms. Cmbridge University Press. Biccheiri, C. and H. Mercier. No Date. “Norms and Beliefs: How Change Occurs” in The Dynamic View of Norms. Cmbridge University Press. Kandel, N., A.Rajbhandari and J. Lamichanne. "Chhue, Chhaupadi and Chueekula Pratha" – Menstrual Sheds: Examples of Discriminatory Practices against Women in the Mid- and Far-Western Regions of Nepal: Considering Women as "Impure” or “Unclean" During Menstruation and Post-Partum Periods. Prepared by Sumon Kamal Tuladhar, Ed.D Education Specialist UNICEF Nepal Country Office July 14, 2012